Select Committee on Crime Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tabled Papers-0471St

FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT Register of Tabled Papers – First Session – Forty–Seventh Parliament 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND REGISTER OF TABLED PAPERS FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 3 NOVEMBER 1992 1 P ROCLAMATION CONVENING PARLIAMENT: The House met at ten o'clock a.m. pursuant to the Proclamation of Her Excellency the Governor bearing the date the Fifteenth day of October 1992 2 COMMISSION TO OPEN PARLIAMENT: Her Excellency the Governor, not being able conveniently to be present in person this day, has been pleased to cause a Commission to be issued under the Public Seal of the State, appointing Commissioners in Order to the Opening and Holding of this Session of Parliament 3 M EMBERS SWORN: The Premier (Mr W.K. Goss) produced a Commission under the Public Seal of the State, empowering him and two other Members of the House therein named, or any one or more of them, to administer to all or any Members or Member of 4 the House the oath or affirmation of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen required by law to be taken or made and subscribed by every such Member before he shall be permitted to sit or vote in the said Legislative Assembly 5 The Clerk informed the House that the Writs for the various Electoral Districts had been returned to him severally endorsed WEDNESDAY, 4 NOVEMBER 1992 6 O PENING SPEECH OF HER EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR: At 2.15 p.m., Her Excellency the Governor read the following speech THURSDAY, 5 NOVEMBER 1992 27 AUTHORITY TO ADMINISTER OATH OR AFFIRMATION OF ALLEGIANCES TO M EMBERS: Mr Speaker informed the House that Her Excellency the Governor had been pleased to issue a Commission under the Public Seal of the State empowering him to administer the oath or affirmation of allegiance to such Members as might hereafter present themselves to be sworn P ETITIONS: The following petitions, lodged with the Clerk by the Members indicated, were received - 28 Mr Veivers from 158 petitioners praying for an increase in the number of police on the Gold Coast. -

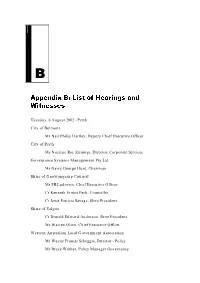

Appendix B: List of Hearings and Witnesses

B Appendix B: List of Hearings and Witnesses Tuesday, 6 August 2002 - Perth City of Belmont Mr Neil Philip Hartley, Deputy Chief Executive Officer City of Perth Ms Noelene Rae Jennings, Director, Corporate Services Governance Systems Management Pty Ltd Mr Garry George Hunt, Chairman Shire of Gnowangerup Council Mr FB Ludovico, Chief Executive Officer Cr Kenneth Ernest Pech, Councillor Cr Janet Patricia Savage, Shire President Shire of Yalgoo Cr Donald Edward Anderson, Shire President Mr Warren Olsen, Chief Executive Officer Western Australian Local Government Association Mr Wayne Francis Scheggia, Director - Policy Mr Bruce Wittber, Policy Manager Governance 166 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT Wednesday, 4 September 2002 - Canberra Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales Mr Peter Conlon, Former Secretary Cr Susan Whelan, Deputy Chairperson Crookwell Shire Council Mr Brian Wilkinson, General Manager Department of Transport and Regional Services Ms Julia Evans, Acting Director, Review of Non-Road Transport Industry Programs Mr Andrew Hrast, Director, Roads to Recovery Program Mr Mike Mrdak, First Assistant Secretary, Territories and Local Government Division Ms Diane Podlich, Assistant Director, Economic Policy, Territories and Local Government Division Mr Geof Watts, Director, Economic Policy, Territories and Local Government National Farmers Federation Miss Denita Harris, Policy Manager & Industrial Relations Advocate Mr Michael Potter, Policy Manager, Economics The Commonwealth Grants Commission -

The Poultry Industry Regulations of 1946 Queensland Reprint

Warning “Queensland Statute Reprints” QUT Digital Collections This copy is not an authorised reprint within the meaning of the Reprints Act 1992 (Qld). This digitized copy of a Queensland legislation pamphlet reprint is made available for non-commercial educational and research purposes only. It may not be reproduced for commercial gain. ©State of Queensland "THE POULTRY INDUSTRY REGULATIONS OF 1946" Inserted by regulations published Gazette 3 March 1947, p. 761; and amended by regulations published Gazette 13 November 1968, p. 2686; 23 July, 1949, p. 224; 25 March 1950, p. 1166; 20 January 1951, p. 162; 9 June 1951, p. 686; 8 November 1952, p. 1136; 16 May 1953, p. 413; 2 July 1955, p. 1118; 3 March 1956, p. 633; 5 April 1958, p. 1543; 14 June 1958, p. 1488, 13 December 1958, p. 1923; 25 April 1959, p. 2357; 10 October 1959, p. 896; 12 December 1959, p. 2180; 12 March 1960, pp. 1327-30; 2 April 1960, p. 1601; 22 April1961, p. 22.53; 11 August 1962, p. 1785; 23 November 1963, p. 1011; 22 February 1964, p. 710; 7 March 1964, p. 865; 16 January 1965, p. 117; 3 July 1965, p. 1323; 12 February 1966, p. 1175; 26 February 1966, p. 1365; 16 April 1966, p. 1983; 7 May 1966, pp. 160-1; 9 July 1966, p. 1352; 27 August 1966, p. 2022. Department of Agriculture and Stock, Brisbane, 27th February, 1947. HIS Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has, in pursuance of the provisions of "The Poultry Industry Act of 1946," been pleased to make the following Regulations:- 1. -

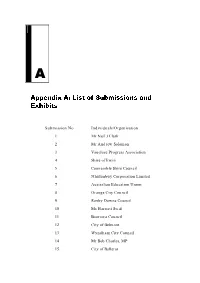

Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits

A Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits Submission No Individuals/Organisation 1 Mr Neil J Clark 2 Mr Andrew Solomon 3 Vaucluse Progress Association 4 Shire of Irwin 5 Coonamble Shire Council 6 Nhulunbuy Corporation Limited 7 Australian Education Union 8 Orange City Council 9 Roxby Downs Council 10 Ms Harriett Swift 11 Boorowa Council 12 City of Belmont 13 Wyndham City Council 14 Mr Bob Charles, MP 15 City of Ballarat 148 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT 16 Hurstville City Council 17 District Council of Ceduna 18 Mr Ian Bowie 19 Crookwell Shire Council 20 Crookwell Shire Council (Supplementary) 21 Councillor Peter Dowling, Redland Shire Council 22 Mr John Black 23 Mr Ray Hunt 24 Mosman Municipal Council 25 Councillor Murray Elliott, Redland Shire Council 26 Riddoch Ward Community Consultative Committee 27 Guyra Shire Council 28 Gundagai Shire Council 29 Ms Judith Melville 30 Narrandera Shire Council 31 Horsham Rural City Council 32 Mr E. S. Cossart 33 Shire of Gnowangerup 34 Armidale Dumaresq Council 35 Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales 36 City of Glen Eira 37 District Council of Ceduna (Supplementary) 38 Mr Geoffrey Burke 39 Corowa Shire Council 40 Hay Shire Council 41 District Council of Tumby Bay APPENDIX A: LIST OF SUBMISSIONS AND EXHIBITS 149 42 Dalby Town Council 43 District Council of Karoonda East Murray 44 Moonee Valley City Council 45 City of Cockburn 46 Northern Rivers Regional Organisations of Councils 47 Brisbane City Council 48 City of Perth 49 Shire of Chapman Valley 50 Tiwi Islands Local Government 51 Murray Shire Council 52 The Nicol Group 53 Greater Shepparton City Council 54 Manningham City Council 55 Pittwater Council 56 The Tweed Group 57 Nambucca Shire Council 58 Shire of Gingin 59 Shire of Laverton Council 60 Berrigan Shire Council 61 Bathurst City Council 62 Richmond-Tweed Regional Library 63 Surf Coast Shire Council 64 Shire of Campaspe 65 Scarborough & Districts Progress Association Inc. -

Valuing Ecosystem Goods and Services

Ecological Economics 50 (2004) 163–194 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon METHODS Valuing ecosystem goods and services: a new approach using a surrogate market and the combination of a multiple criteria analysis and a Delphi panel to assign weights to the attributes Ian A. Curtis* School of Environmental Studies and Geography, Faculty of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, P.O. Box 6811 Cairns, Queensland 4870, Australia Received 22 February 2003; received in revised form 5 February 2004; accepted 20 February 2004 Available online 25 September 2004 Abstract A new approach to valuing ecosystem goods and services (EGS) is described which incorporates components of the economic theory of value, the theory of valuation (US f appraisal), a multi-model multiple criteria analysis (MCA) of ecosystem attributes, and a Delphi panel of experts to assign weights to the attributes. The total value of ecosystem goods and services in the various tenure categories in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area (WTWHA) in Australia was found to be in the range AUD$188 to $211 million yearÀ 1, or AUD$210 to 236 haÀ 1 yearÀ 1 across tenures, as at 30 June 2002. Application of the weightings assigned by the Delphi panelists and assessment of the ecological integrity of the various tenure categories resulted in values being derived for individual ecosystem services in the World Heritage Area. Biodiversity and refugia were the two attributes ranked most highly at AUD$18.6 to $20.9 million yearÀ 1 and AUD$16.6 to $18.2 million yearÀ 1, respectively. D 2004 Elsevier B.V. -

Queensland Government Gazette

[591] Queensland Government Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXVII] (337) FRIDAY, 22 OCTOBER, 2004 [No. 39 Integrated Planning Act 1997 TRANSITIONAL PLANNING SCHEME NOTICE (NO. 2) 2004 In accordance with section 6.1.11(2) of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, I hereby nominate the date specified in the following schedule as the revised day on which the transitional planning scheme, for the local government area listed in the schedule, will lapse: SCHEDULE Townsville City 31/12/04 Desley Boyle MP Minister for Environment, Local Government, Planning and Women 288735—1 592 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, No. 39 [22 October, 2004 Adopted Amendment to the Planning Scheme: Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan Section 6.1.6 of the Integrated Planning Act 1997 The provisions of the Integrated Planning and Other Legislation Act 2003 (IPOLAA 2003) commenced on 4 October 2004, and in accordance with the conditions of approval for the Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan (CMRNICP) issued by the Minister for Local Government and Planning dated 18 May 2004 and 3 June 2004, Council: - Previously adopted on 10 June 2004, an amendment to the planning scheme for the Shire of Noosa by incorporating the infrastructure charges plan, the Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan (CMRNICP) applying to “exempt and self-assessable” development; and - On 14 October 2004, adopted an amendment to the planning scheme for the Shire of Noosa by incorporating “the balance of” the Coastal -

Select Committee on Crime Prevention

SELECT COMMITTEE ON CRIME PREVENTION FIRST REPORT JUNE 1999 Further copies are available from - State Law Publisher 10 William Street PERTH WA 6000 Telephone: (08) 9321 7688 Facsimile: (08) 9321 7536 Email: [email protected] Published by the Legislative Assembly, Perth, Western Australia 6000 Printed by the Government Printer, State Law Publisher SELECT COMMITTEE ON CRIME PREVENTION FIRST REPORT Presented by: Hon. R K Nicholls, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly on 17 June 1999 Select Committee on Crime Prevention Select Committee on Crime Prevention Terms of Reference (1) That this House appoints a Select Committee to inquire into and report on programs, practices and community action which have proven effective in - (a) reducing or preventing crime and anti-social behaviour at the community level; (b) addressing community and social factors which contribute to crime and anti-social behaviour in the community; and (c) addressing community and anti-social behaviour after it has occurred. (2) That the Committee also report on methods by which such information may best be accessed by the community. (3) That the Committee have the power to send for persons and papers, to sit on days over which the House stands adjourned, to move from place to place, to report from time to time, and to confer with any committee of the Legislative Assembly as it thinks appropriate. (4) That the Committee finally report on 30 November 1998. Extension to Reporting Date On 26 November 1998 the House resolved that the reporting date be extended to 30 April 1999. On 21 April 1999 the House resolved that the reporting date be extended to 1 July 1999. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1910

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 29 NOVEMBER 1910 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 2368 Questions. [ASSEMBLY.] Questions. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. GOWRIE REPURCHASED ESTATE. Mr. LESINA (Cle1·mont) asked the Secre TUESDAY, 29 NOVEMBER, 1910. tary for Public Lands- Has his attention been drawn to the passage in the Auditor-General's report, wherein he states that the Lands Department has taken no action either The DEPUTY SPEAKER (W. D. Armstrong, to recover arrears due on selections in the Gowrie Esq., Lockyer) took the chair wt half-past Repurchased Estate, or to put in force the for 3 o'clock. feiture clauses in respect to those selections? PAPERS. T·he SECRETARY FOR PUBLIC LANDS (Hon. D. F. Denham, Oxley) replied~ The following papers, laid on the table, The Auditor~General's conclusions are not well were ordered to be printed:- founded- The Twenty-first annual report of the ( a) The Lands Department has taken such Hydrauliq Engineer. action as the conditions warranted, and I Despatch from the Secretary of State for haYe made inquiry personally and on the the Colonies, relating to Act passed spot; during session of 1910. (b) For a radius of about 5 miles round Gowrie Homestead crops failed season after season from want of rain or other cause, whilst NEW TECHNICAL COLLEGE. surrounding areas produced normal results; (c) Forfeiture under the circumstances would The PREMIER : I would like to announce have been unjustifiable; that the plans of ·the proposed buildings in (d) Selectors in arrear will pay interest at the connection with the Central Technical College rate of 5 per cent. -

![St Columb Ltd V Department of Natural Resources and Water [2006] QLC 67](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7481/st-columb-ltd-v-department-of-natural-resources-and-water-2006-qlc-67-11097481.webp)

St Columb Ltd V Department of Natural Resources and Water [2006] QLC 67

LAND COURT OF QUEENSLAND CITATION: St Columb Ltd v Department of Natural Resources and Water [2006] QLC 67 PARTIES: St Columb Ltd (appellant) v. Chief Executive, Department of Natural Resources and Water (respondent) FILE NO: AV2005/0608 DIVISION: Land Court of Queensland PROCEEDING: Appeal against an annual valuation of land under the Valuation of Land Act 1944. DELIVERED ON: 20 October 2006 DELIVERED AT: Brisbane HEARD AT: Cairns MEMBER: Mr RS Jones ORDER: Appeal AV 2005/0608 is allowed and the unimproved value of Lot 4 on Crown Plan CWL 369, Parish of Dunkalli is determined in the amount of one million one hundred thousand dollars ($1,100,000). CATCHWORDS: S.33 Valuation of Land Act 1944 – Presumption of correctness of statutory valuation – comparable sales – unacceptable sales – relativity with other unimproved values. APPEARANCES: Mr Veall, for the appellant Mr W Isdale of Crown Law for the respondent. [1] St Columb Ltd, the appellant, has appealed against the assessment of the unimproved value of its land by the Chief Executive, Department of Natural Resources and Water, the respondent to the appeal. [2] The unimproved value determined by the respondent pursuant to the Valuation of Land Act 1944 as at 1 October 2004 (effective as at 30 June 2005) is $1,300,000. In its notice of appeal, the appellant's estimate of the unimproved value was $500,000 but at the hearing of the appeal it contended for a value of $650,000. [3] The appellant was represented by Mr I Veall, a director of the appellant company. The respondent was legally represented by Mr W Isdale of counsel employed by Crown Law. -

I I I I I I I I I COASTAL OBSERVA'llon PROGRAMME - ENGINEERING (COPE) HULL Heam- CARDWELL SHIRE I for TBE YEARS 1979 to 1988 REPORT NO

I I I I I I I I I COASTAL OBSERVA'llON PROGRAMME - ENGINEERING (COPE) HULL HEAm- CARDWELL SHIRE I FOR TBE YEARS 1979 TO 1988 REPORT NO. C26.1 I I I I I I_ I Beach Protection Authority December 1989 I_' I I I I I I I I This report was prepared by the Beach Protection Branch of the Department of Harbours I and Marine on behalf of the Beach Protection Authority. All reasonable care and attention has been exercised in the collection, processing and I compilation of the COPE data included in this report. However, the accuracy and reliability of this information is not guaranteed in any way by the Beach Protection Authority and the Authority accepts no responsibility for the use of this information in I any way whatsoever. I I I I I I I I I I I DOCUMENTA'llONPAGE I REPORT NO.:.-- C26.l TITLE:.-- Report - Coastal Observation Programme - Engineering (COPE), I Hull Heads - Cardwell Shire DATE:.-- December 1989 I TYPE OF REPORT:.-- Technical Memorandum PREPARED BY:.-- Coastal Management Programme of the Department of Harbours and Marine on behalf of the Beach Protection I Authority. ISSUING ORGANISA'llON:.-- Beach Protection Authority I G.P.O. BOX 2595 BRISBANE QLD 4001 AUSTRALIA I DJSTRIBUI'ION:.-- Public Distribution I This report provides a summary of primary analyses of COPE data on wind, wave and beach processes observed at Hull Heads in the Shire of Cardwell, on the north Queensland I coast. The data was recorded by volunteer observers during the period December 1979 to December 1988. -

Hansard 29 March 1995

Legislative Assembly 11521 29 March 1995 WEDNESDAY, 29 MARCH 1995 typically vitriolic Labor Party attack. Senator Ray went into detail, recounting in the Senate happenings in that House on 20 May 1993 by way of establishing an alibi. He also claimed to Mr SPEAKER (Hon. J. Fouras, Ashgrove) have never been to the Park Lane Hotel. read prayers and took the chair at 2.30 p.m. At no time have I suggested a time, a date or a venue for the meeting referred to in my speech yesterday. The attack on me was PETITIONS based on allegations that were never made. The Clerk announced the receipt of the following petitions— GENERAL BUSINESS—NOTICE OF MOTION No. 1 TAFE Tutors Sheffield Shield Final From Mr J. N. Goss (130 signatories) Mr BORBIDGE (Surfers Paradise— praying that the Parliament of Queensland will Leader of the Opposition) (2.36 p.m.): In the reconsider the withdrawal of funding for tutors absence of the honourable member for employed at TAFE institutions. Southport, who is attending the funeral of a close family friend, I formally move— Royal Queensland Bush Children's "That this House— Health Scheme (a) commends the Queensland cricket From Mr Lester (694 signatories) team, the mighty Bulls, for their praying that the Parliament of Queensland will: outstanding and historic victory in the (a) immediately remove the board and Sheffield Shield Final at the Gabba, executive staff of the Royal Queensland Bush where the Crows were well and truly Children's Health Scheme and appoint an stoned; administrator as an interim manager; (b) (b) notes the legendary contribution of immediately reopen the Townsville and Allan Border to Queensland Cricket Yeppoon Homes and retain all homes in their where the Shield win has capped a coastal communities; and (c) ensure that great career; and community input is sought, as a funding (c) further notes the great performance requirement, prior to any proposed future of that other 'oldie'—Carl changes in administering the scheme. -

Downloaded from Over the Location and Density of Dwelling Unit Development In

QueenslandQueensland Government Government Gazette Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 345] Friday, 6 July, 2007 You can advertise in the Gazette! ADVERTISING RATE FOR A QUARTER PAGE $500+gst (casual) Contact your nearest representative to fi nd out more about the placement of your advertisement in the weekly Queensland Government Gazette Qld : Liz McKenzie - mobile: 0408 014 591 - email: [email protected] NSW : Jonathon Tremain - phone: 02 9499 4599 - email: [email protected] [1171] QueenslandQueensland Government Government Gazette Gazette Extraordinary PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 345] Monday, 2 July, 2007 [No. 58 Mental Health Act 2000 Mental Health Act 2000 Declaration of Authorised Mental Health Service Declaration of Authorised Mental Health Service Department of Health Department of Health Brisbane, 29 June 2007 Brisbane, 29 June 2007 This declaration is made under section 495 of the Mental Health Act This declaration is made under section 495 of the Mental Health Act 2000 and amends the declaration made on 15 July 2005. 2000 and amends the declaration made on 16 February 2007. Dr Aaron Groves Dr Aaron Groves Director of Mental Health Director of Mental Health Central Queensland Network Authorised Mental Health Service Wide Bay Authorised Mental Health Service Component Facilities Address Component facilities Address Rockhampton Hospital in- Canning Street, patient and specialist health Rockhampton, Q 4700 Bundaberg Hospital in-patient Bourbong Street, units