Quercus Prinoides, the Dwarf Chinkapin Oak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aromatic Aster an Emphasis on Saving Bees

2019 GREATPLANTS GARDENER NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM “ We plant Nebrasks for healthy homes, vibrant communities and a resilient environment. A Focus on Mother Nature— from Me to She Bob Henrickson, GreatPlants® Coordinator What do gardeners want? A stronger connection with nature, according to the 2019 Garden Trends Report. The trend is a movement from the Me to the She gen- eration, with a focus on Mother Nature. The strongest motivation to save the natu- ral world is to love it; and with our own fate so closely tied to our environment, caring for it in turn nurtures ourselves. Another trend is gardeners’ recognition of the “thinning of the insect world.” Recent years have seen Aromatic Aster an emphasis on saving bees. In coming years we need to extend that care to all Perennial of the Year beneficial insects by planting more natives that provide the pollen and nectar native Symphyotrichum insects rely on. While Rachel Carson’s oblongifolium Silent Spring warned of bird die-off INSIDE from pesticides in the 1960s, that threat Height: 2-4 feet high continues for bees and other pollinators, An Aster for Every Garden 5 40 percent of which risk global extinction. Spread: 2-3 feet wide Conserving Chinkapin Oaks 7 Sun: full sun More people are gardening, and more money is being spent on lawn and garden Small Oaks and Hybrids 8 Soil: dry to medium plants and products, than ever before. The Balm for the Bees 9 A native of the plains with narrow average household set a spending record leaves and a dramatic abundance of $503, up nearly $100 over the previous Milkweeds: Beauties, Beasts 10 year. -

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha's Vineyard

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard Timothy M. Boland, Executive Director, The Polly Hill Arboretum, West Tisbury, MA 02575 USA Martha’s Vineyard is many things: a place of magical beauty, a historical landscape, an environmental habitat, a summer vacation spot, a year-round home. The island has witnessed wide-scale deforestation several times since its settlement by Europeans in 1602; yet, remarkably, existing habitats rich in biodiversity speak to the resiliency of nature. In fact, despite repeated disturbances, both anthropogenic and natural (hurricanes and fire), the island supports the rarest ecosystem (sand plain) found in Massachusetts (Barbour, H., Simmons, T, Swain, P, and Woolsey, H. 1998). In particular, the scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh.) dominates frost bottoms and outwash plains sustaining globally rare lepidopteron species, and formerly supported the existence of an extinct ground-dwelling bird, a lesson for future generations on the importance of habitat preservation. European Settlement and Early Land Transformation In 1602 the British merchant sailor Bartholomew Gosnold arrived in North America having made the six-week boat journey from Falmouth, England. Landing on the nearby mainland the crew found abundant codfish and Gosnold named the land Cape Cod. Further exploration of the chain of nearby islands immediately southwest of Cape Cod included a brief stopover on Cuttyhunk Island, also named by Gosnold. The principle mission was to map and explore the region and it included a dedicated effort to procure the roots of sassafras (Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees) which were believed at the time to be medicinally valuable (Banks, 1917). -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Key to Leaves of Eastern Native Oaks

FHTET-2003-01 January 2003 Front Cover: Clockwise from top left: white oak (Q. alba) acorns; willow oak (Q. phellos) leaves and acorns; Georgia oak (Q. georgiana) leaf; chinkapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii) acorns; scarlet oak (Q. coccinea) leaf; Texas live oak (Q. fusiformis) acorns; runner oak (Q. pumila) leaves and acorns; background bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) bark. (Design, D. Binion) Back Cover: Swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii) leaves and acorns. (Design, D. Binion) FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Oak Identification Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America John Stein and Denise Binion Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 Robert Acciavatti Forest Health Protection Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 United States Forest FHTET-2003-01 Department of Service January 2003 Agriculture NORTH AMERICA 100th Meridian ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank all those who helped with this publication. We are grateful for permission to use the drawings illustrated by John K. Myers, Flagstaff, AZ, published in the Flora of North America, North of Mexico, vol. 3 (Jensen 1997). We thank Drs. Cynthia Huebner and Jim Colbert, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Disturbance Ecology and Management of Oak-Dominated Forests, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Martin MacKenzie, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Steven L. Stephenson, Department of Biology, Fairmont State College, Fairmont, WV; Dr. Donna Ford-Werntz, Eberly College of Arts and Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV; Dr. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: an Update

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 3/19/02 (2002), Volume 95, #4, pp. 261-284 accepted 6/23/02 The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: An Update Nick A. Stoynoff Glenbard East High School Lombard, IL 60148 William J. Hess The Morton Arboretum Lisle, IL 60532 ABSTRACT This paper updates the distribution of members of the black oak [section Lobatae] and white oak [section Quercus] groups native to Illinois. In addition a brief discussion of Illinois’ spontaneously occurring hybrid oaks is presented. The findings reported are based on personal collections, herbarium specimens, and published documents. INTRODUCTION The genus Quercus is well known in Illinois. Although some taxa are widespread, a few have a limited distribution. Three species are of “special concern” and are listed as either threatened (Quercus phellos L., willow oak; Quercus montana Willd., rock chestnut oak) or endangered (Quercus texana Buckl., Nuttall’s oak) [Illinois Endangered Species Pro- tection Board 1999]. The Illinois Natural History Survey has dedicated a portion of its website [www.INHS.uiuc.edu] to the species of Quercus in Illinois. A discussion of all oaks from North America is available online from the Flora of North America Associa- tion [http://hua.huh.harvard.edu/FNA/] and in print [Jensen 1997, Nixon 1997, Nixon and Muller 1997]. The National Plant Data Center maintains an extensive online database [http://plants.usda.gov] documenting information on plants in the United States and its territories. Extensive oak data are available there [U.S.D.A. 2001]. During the last 40 years the number of native oak species recognized for Illinois by vari- ous floristic authors has varied little [Tables 1 & 2]. -

Quercus Muehlenbergii Engelm. Chinkapin Oak Fagaceae Beech Family

Quercus muehlenbergii Engelm. Chinkapin Oak Fagaceae Beech family Ivan L. Sander Chinkapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii), some- generally found on well-drained upland soils derived times called yellow chestnut oak, rock oak, or yellow from limestone or where limestone outcrops occur. oak, grows in alkaline soils on limestone outcrops Occasionally it is found on well-drained limestone and well-drained slopes of the uplands, usually with soils along streams. It appears that soil pH is strong- other hardwoods. It seldom grows in size or abun- ly related to the prescence of chinkapin oak, which dance to be commercially important, but the heavy is generally found on soils that are weakly acid (pH wood makes excellent fuel. The acorns are sweet and about 6.5) to alkaline (above pH 7.0). It grows on are eaten by several kinds of animals and birds. both northerly and southerly aspects but is more common on the warmer southerly aspects. It is ab- Habitat sent or rare at high elevations in the Appalachians (3,4). Native Range Chinkapin oak (fig. 1) is found in western Vermont Associated Forest Cover and New York, west to southern Ontario, southern Michigan, southern Wisconsin, extreme southeastern Minnesota, and Iowa; south to southeastern Nebras- Chinkapin oak is rarely a predominant tree, but it ka, eastern Kansas, western Oklahoma, and central grows in association with many other species. It is a Texas; east to northwest Florida; and north mostly component of the forest cover type White Oak-Black in the mountains to Pennsylvania and southwestern Oak-Northern Red Oak (Society of American Massachusetts. -

Terrestrial & Palustrine Plant Communities of Pennsylvania 2Nd

Terrestrial & Palustrine Plant Communities of Pennsylvania 2nd Ed. Section 3 Terrestrial Communities Serpentine pitch pine - oak forest This community type is part of the "Serpentine barrens complex." It occurs in areas underlain by serpentine bedrock where soil development has proceeded far enough to support forest vegetation, but not so far as to override the influence of serpentine chemistry on species composition. Fire is an important factor in the establishment and persistence of pitch pine. In the absence of fire, pine is likely to decrease in favor of hardwood species. Characteristic overstory species include Quercus stellata (post oak), Q. marilandica (blackjack oak), Pinus rigida (pitch pine), Sassafras albidum (sassafras), Juniperus virginiana (red-cedar), Nyssa sylvatica (black-gum), Populus grandidentata (large-toothed aspen), and Robinia pseudoacacia (black locust)—which is generally invasive in these systems. The shrub layer is often dominated by an impenetrable tangle of Smilax rotundifolia (greenbrier) and S. glauca (catbrier). Q. prinoides (chinquapin oak) occurs in the understory and in openings; Quercus ilicifolia (scrub oak) is also present in openings. Low shrub species include Vaccinium pallidum (lowbush blueberry), V. stamineum (deerberry), and Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry). Herbaceous species include Pteridium aquilinum (bracken fern), Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla), and a variety of graminoids. Related types: The "Serpentine Virginia pine - oak forest" type also occurs on serpentinite-derived soils and shares many species with this type. The Virginia pine type is dominated by a mixture of Pinus virginiana and various oaks. P. virginiana produces denser shade and thicker litter than does P. rigida. Herbaceous and shrub growth under P. virginiana is generally sparse. -

IOS Returns to the Morton for 8Th Conference He 8Th Conference of the Interna- T Tional Oak Society Was a Delight- Ful Event

Oak News & Notes The Newsletter of the International Oak Society, Volume 20, No. 1, 2016 IOS Returns to the Morton for 8th Conference he 8th Conference of the Interna- T tional Oak Society was a delight- ful event. In honor of the organiza- tion’s 21st year, the Conference was held in Lisle, Illinois, at The Morton Arboretum – the host site of the first Conference in 1994. A total of 188 people were in attendance, represent- ing 15 different countries. The event was graciously hosted by Dr. Gerard Donnelly, President and CEO of The Morton Arboretum, and Dr. Andrew Hipp, Senior Scientist in Systematics and Herbarium Curator of The Morton Arboretum. This year’s Conference boasted an im- pressive 26 presentations and 8 work- shops on a myriad of topics, as well as The Conference Committee (clockwise from top left): Henry “Weeds” Eilers, Nick Stoynoff, Andrew Hipp, Megan Dunning, Guy Sternberg, Jim Hitz, Nicole Cavender, Murphy Westwood, Alana McKean, Joe Roth- 9 poster sessions. Presenters highlight- leutner (not in photo: Matt Lobdell). Thank you all for a great job! Photo: ©Guy Sternberg. ed species from North America, Mexi- co, and China – discussing topics from Specialist Group. Addressing the issue ent oaks species to help update the da- phylogeny and genomics to evolution of conservation, Sara’s inspirational tabase. Future partnerships between and maintenance. Horticultural re- presentation echoed the sentiments of the IUCN, The Morton Arboretum, searchers shared the latest in breeding, the International Oak Society’s mis- and the IOS are anticipated. clonal reproduction, and cultivation sion of preservation. The IUCN, or techniques. -

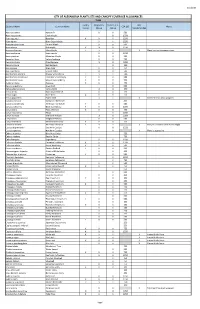

City of Alexandria Plant Lists and Canopy Coverage Allowances Trees

3/1/2019 CITY OF ALEXANDRIA PLANT LISTS AND CANOPY COVERAGE ALLOWANCES TREES Locally Regionally Eastern U.S. Not Botanical Name Common Name CCA (SF) Notes Native Native Native Recommended Abies balsamea Balsam Fir X X 500 Acer leucoderme Chalk Maple X 1250 Acer negundo Boxelder X X X 1250 Acer nigrum Black Sugar Maple X X 1250 Acer pensylvanicum Striped Maple X X 500 Acer rubrum Red maple X X X 1250 Acer saccharinum Silver Maple X X X X Plant has maintenance issues. Acer saccharum Sugar maple X X 1250 Acer spicatum Mountain Maple X X 500 Aesculus flava Yellow Buckeye X X 750 Aesculus glabra Ohio Buckeye X X 1250 Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye X 500 Alnus incana Gray Alder X X 750 Alnus maritima Seaside Alder X X 500 Amelanchier arborea Downy Serviceberry X X X 500 Amelanchier canadensis Canadian Serviceberry X X X 500 Amelanchier laevis Smooth Serviceberry X X X 750 Asimina triloba Pawpaw X X X 750 Betula populifolia Gray Birch X 500 Betula alleghaniensis Yellow Birch X X 750 Betula lenta Black (Sweet) birch X X 750 Betula nigra River birch X X X 750 Betula papyrifera Paper Birch X X X Northern/mountain adapted. Carpinua betulus European Hornbeam 250 Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam X X X 500 Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory X X X 1250 Carya glabra Pignut Hickory X X X 750 Carya illinoinensis Pecan X 1250 Carya laciniosa Shellbark Hickory X X 1250 Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory X X 500 Carya tomentosa Mockernut Hickory X X X 750 Castanea dentata American Chestnut X X X X Not yet recommended due to Blight Catalpa bignonioides Southern Catalpa X X 1250 Catalpa speciosa Northern Catalpa X X Plant is aggressive. -

Hybrid Oaks (Quercus Spp.) of Georgia K.D

Hybrid Oaks (Quercus spp.) of Georgia K.D. Coder Publication WSFNR-20-26A April 2020 Hybrid Oaks (Quercus spp.) of Georgia Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources The native oaks of Georgia are many and varied. Each has the capacity to interbreed or hybridize with surrounding oak species which are close relatives. Georgia’s hybrid oaks can be difficult to identify due to much gene sharing, cross-breeding, and associated variable leaf and acorn appearance. This publication helps professionals appreciate and understand oak hybrids in Georgia. Oak Hybrids -- A Success Strategy One means of oak genetic variation is generated by hybridization, leading to population divergence and specialization. Hybridization occurs naturally and can evolve into stable, genetically distinct populations and even species. Hybridization can generate new combinations of adaptations, by transferring or combining phenotypic features. (Niklas 2016) Hybridization of oaks played a significant role in their evolution. (Petit et.al. 2003) In addition to oak appearance and form, hybridization has also provided resistance-sharing among oak species to combat pathogens. (Hauser et.al. 2017) Oaks have been long known to exchange gene sets across species boundaries through hybridization and backcrossing. (Crowl et.al. 2019) Introgression is backcrossing with the parent species, and can generate some level of fixation of gene sets and physical features. (Niklas 2016) Hybridization and introgression events in oaks have occurred often, and has helped to solidify traits and adaptations. (Crowl et.al. 2019) Closely related oaks with similar reproductive strategies and overlapping geographical ranges often hybridize naturally.