Biogeography and Conservation of Andean and Trans-Andean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

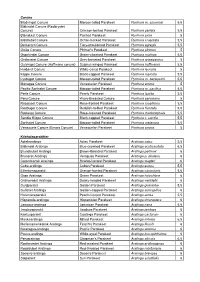

Rødbrystet Conure

Conure Blodvinget Conure Maroon -tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. souancei 5,5 Blåkindet Conure (Rødbrystet Conure) Crimson-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura perlata 5,5 Blånakket Conure Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta 5 Blåstrubet Conure Ochre-marked Parakeet Pyrrhura cruentata 5,5 Demerara Conure Fiery-shouldered Parakeet Pyrrhura egregia 5,5 Goiás Conure Pfrimer's Parakeet Pyrrhura pfrimeri 5 Grønkindet Conure Green-cheeked Parakeet Pyrrhura molinae 5,5 Gråbrystet Conure Grey-breasted Parakeet Pyrrhura griseipectus 5 Gulvinget Conure (Hoffmans conure) Sulphur-winged Parakeet Pyrrhura hoffmanni 5,5 Hvidøret Conure White-eared Parakeet Pyrrhura leucotis 5 Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura rupicola 5,5 Lysbuget Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. berlepschi 5,5 Monagas Conure Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Pacific Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. pacifica 5,5 Perle Conure Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida 5,5 Peru Conure Wavy-Breasted Conure Pyrrhura peruviana 5 Rosaisset Conure Rose-fronted Parakeet Pyrrhura roseifrons 5,5 Rødbuget Conure Reddish-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura frontalis 5,5 Rødisset Conure Rose-crowned Parakeet Pyrrhura rhodocephala 5,5 Sandia Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura r. sandia 5,5 Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura melanura 5,5 Venezuela Conure (Emma Conure) Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Kilehaleparakitter Aztekaratinga Aztec Parakeet Aratinga astec 5,5 Blåkindet Aratinga Blue-crowned Parakeet Aratinga acuticaudata 6,5 Brunstrubet Aratinga Brown-throated Parakeet -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 Under the Biosecurity Act 2015

New South Wales Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 His Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Biosecurity Act 2015. NIALL BLAIR, MLC Minister for Primary Industries Explanatory note The objects of this Regulation are: (a) to update the lists of pests and diseases of plants, pests and diseases of animals, diseases of aquatic animals, pest marine and freshwater finfish and pest marine invertebrates (set out in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Act)) that are prohibited matter throughout the State, and (b) to update the description (set out in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Act) of the part of the State in which Daktulosphaira vitifoliae (Grapevine phylloxera) is a prohibited matter, and (c) to include (in Schedule 3 to the Act) lists of non-indigenous amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles in respect of which dealings are prohibited or permitted, and (d) to provide (in Schedule 4 to the Act) that certain dealings with bees and certain non-indigenous animals require biosecurity registration, and (e) to update savings and transitional provisions with respect to existing licences (in Schedule 7 to the Act). This Regulation is made under the Biosecurity Act 2015, including sections 27 (4), 151 (2), 153 (2) and 404 (the general regulation-making power) and clause 1 (1) and (5) of Schedule 7. Published LW 2 June 2017 (2017 No 230) Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 [NSW] Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 1 Name of Regulation This Regulation is the Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017. -

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Birds (Aves), Serrania Sadiri, Parque Nacional Madidi, Depto. La Paz, Bolivia Peter Andrew Hosner 1 Kenneth David Behrens 2 A. Bennett Hennessey 3 1 University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Division of Ornithology. Dyche Hall, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66046. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tropical Birding, 1 Toucan Way. Bloubergrise 7441, South Africa. 3 Asociación Civil Armonía. Avenida Lomas de Arena, Casilla 3566, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Abstract We surveyed the Serrania Sadiri for birds at elevations between 500-950m for a combined total of 15 days in three different months. The area surveyed was along the Tumupasa/San Jose de Uchupiamones trail at the edge of Parque Nacional Madidi in Depto. La Paz, Bolivia. We report observations of 231 species of birds detected by sight and sound, including many outlying ridge specialists. We report and present photographs of a new species for Depto. La Paz (Caprimulgis nigrescens), the second Bolivian localities for Porphyrolaema prophyrolaema, Zimerius cinereicapillus, and Basileuterus chrysogaster, and five new species records for Parque Nacional Madidi. Introduction Foothills and outlying ridges of the Andes are From the small village of Tumupasa (14°8'46" S, often very difficult or impossible to access. As a 67°53'17" W; 400 m a.s.l; Figures 1 and 2), an old result, many of the specialist bird species in these trail leads generally southwest over the Serrania areas are poorly known and some only recently Sadiri to the town of San Jose de Uchupiamones described, and these areas generally have unique (14°12'47" S, 68°03'14" W; 520 m a.s.l). -

Manaus, Brazil: Amazon Rainforest & River Islands

MANAUS, BRAZIL: AMAZON RAINFOREST & RIVER ISLANDS OCTOBER 8-21, 2020 ©2019 The Brazilian city of Manaus is nestled deep in the heart of the incomparable Amazon rainforest, the greatest avian-rich ecosystem on the planet! This colorful, bustling city is perfectly positioned at the junction of the world’s two mightiest rivers, the Amazon and Rio Negro, where vast quantities of the warm, black water of the Negro collide with immense volumes of cooler, silt-laden whitewater of the Amazon flowing down from the Andes. The two rivers flow side-by-side for kilometers before completely mixing (due to the major difference in temperature), forming the famous “wedding of the waters” where two species of freshwater dolphins are regularly seen, including the legendary Pink River Dolphin (males reaching 185 kilograms (408 lbs.) and 2.5 meters (8.2 ft.) in length). A male Guianan Cock-of-the-rock on a lek has to be one of the world’s most spectacular birds. © Andrew Whittaker Manaus, Brazil: Amazon Rainforest & River Islands, Page 2 The Amazon and its immense waterways have formed many natural biogeographical barriers to countless birds and animals, allowing for heightened speciation over countless millions of years. The result is a legion of distinctly different yet sibling species found on opposite river banks. Prime examples on this trip include Gilded versus Black-spotted barbets, Amazonian versus Guianan trogon, Black-necked versus Guianan red-cotinga, White-browed versus Dusky purpletufts, White-necked versus Guianan puffbird, Orange-cheeked versus Caica parrots, White-cheeked versus Rufous-throated antbird, and Rufous-bellied versus Golden-sided euphonia, etc., thus making Manaus a perfect base for the exploration of the exotic mega rich avifauna of the unique heart of Amazonia. -

What Eats Parrots?

Bird Talk Magazine, August 2002 Donald Brightsmith What Eats Parrots? What are the major predators on parrots in the wild? By Donald Brightsmith Originally published in Bird Talk Magazine August 2002 Recently I was asked what animals prey on parrots in the wild. I guess the short answer to that is . not much. In general parrots are quite wary and do a number of things to make sure that they are not captured by predators. They usually feed in groups high in the tree canopies. The high perches and large groups ensures that there are many eyes to spot predators and then an easy escape as they drop from the tall trees. Parrot nests also seem to be chosen to reduce the risk of predation. Most species in predator rich environments, especially the macaws I work with, prefer to nest in high trees in relatively exposed spots from which the adults can watch for danger and take flight quickly if needed. Those species that nest in the forest understory where they are more vulnerable take great precautions to avoid being captured when they return to their nests. I have watched three such species in the wild as they approach their nests, the Cobalt-winged Parakeet, Tui Parakeet and the Gray-cheeked Parakeet. All three of these birds are normally loud and raucous (those who own them as pets will back me up on this one I am sure). They call constantly when in flight, and usually even continue to chatter while feeding. But when they return to their nests it is a very different matter. -

The Psittacine Year: Determinants of Annual Life History Patterns In

The Psittacine Year: What drives annual cycles in Tambopata’s parrots? Donald J. Brightsmith1 Duke University Department of Biology April 2006 Prepared for the VI International Parrot Convention Loro Parque, Tenerife, Spain Introduction Psittacines are notoriously difficult to study in the wild (Beissinger & Snyder 1992). Due to their lack of territorial behavior, vocalization behavior, long distance movements, and canopy dwelling nature, many general bird community studies do not adequately sample parrots (Casagrande & Beissinger 1997; Marsden 1999; Masello et al. 2006). As a result, detailed studies of entire parrot communities are rare (but see Marsden & Fielding 1999; Marsden et al. 2000; Roth 1984). However, natural history information is important for understanding and conserving this highly endangered family (Bennett & Owens 1997; Collar 1997; Masello & Quillfeldt 2002; Snyder et al. 2000). The lowlands of the western Amazon basin harbor the most diverse avian communities in the world (Gentry 1988) with up to 20 species of macaws, parrots, parakeets, and parrotlets (Brightsmith 2004; Montambault 2002; Terborgh et al. 1984; Terborgh et al. 1 Current address: Shubot Exotic Bird Health Center, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA 1990). Psittacine densities can also be very high in this region as hundreds to thousands of parrots congregate daily at riverbanks to eat soil (Brightsmith 2004; Burger & Gochfeld 2003; Emmons 1984; Nycander et al. 1995). These “clay licks” apparently provide an important source of sodium and protect the birds from the toxins in their diets (Brightsmith 2004; Brightsmith & Aramburú 2004; Emmons & Stark 1979; Gilardi et al. 1999). Parrots eat predominantly seeds, unripe fruit, ripe fruit, and flowers, supplemented occasionally with bark and other items (Forshaw 1989; Renton 2006). -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds (Aves) of Cerro Hoya National Park, Azuero Peninsula, Panamá

11 2 1585 the journal of biodiversity data February 2015 Check List LISTS OF SPECIES Check List 11(2): 1585, February 2015 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15560/11.2.1585 ISSN 1809-127X © 2015 Check List and Authors Annotated checklist of the birds (Aves) of Cerro Hoya National Park, Azuero Peninsula, Panamá Matthew J. Miller1*, George R. Angehr1, Robert S. Ridgely2, John Klicka3, Oscar G. López. Ch.1, Jacobo Arauz4, Euclides Campos C.5 and Daniel Buitrago-Rosas1 1 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado Postal 0843-03092, Panamá, Republic of Panama 2 Rainforest Trust, 25 Horner Street, Warrenton, VA 20186, USA 3 University of Washington, Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Seattle, WA 98195-1800, USA 4 Universidad de Panamá, Escuela de Biología, Departamento de Zoología, Panamá, Republic of Panama 5 Apartado Postal 0823-02757, Panamá, Republic of Panama * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Protected only by the extreme ruggedness of and Samaniego 2008), today less than 15% is covered in its terrain, the montane regions of Cerro Hoya National mature forest, with perhaps another 20% covered in sec- Park are among the least biologically known regions of ondary forest. Of the remaining Azuero mature forest, Central America. Here we provide a checklist of 225 bird most can be found in Cerro Hoya National Park and La species recorded from five expeditions to the region over Tronosa Forest Reserve (07.3° N, 080.6° W) found just to the last 18 years, which represents lower species richness the east of Cerro Hoya National Park. -

Mammalian and Avian Diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana

Biota Neotrop., vol. 11, no. 3 Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles1,2, Niall Patrick McCann1 & Ashley Peregrine Holland1 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, School of Biosciences,Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff, Wales, CF103AX Rupununi River Drifters, Karanambu Ranch, Lethem Post Office, Region 9, Rupununi Guyana 2Corresponding author: Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles, e-mail: [email protected] PICKLES, R.S.A., McCANN, N.P. & HOLLAND, A.L. Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana. Biota Neotrop. 11(3): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n3/en/abstract?in ventory+bn00911032011 Abstract: We report the results of a short expedition to the remote headwaters of the River Rewa, a tributary of the River Essequibo in the Rupununi, Southern Guyana. We used a combination of camera trapping, mist netting and spot count surveys to document the mammalian and avian diversity found in the region. We recorded a total of 33 mammal species including all 8 of Guyana’s monkey species as well as threatened species such as lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and bush dog (Speothos venaticus). We recorded a minimum population size of 35 giant otters in five packs along the 95 km of river surveyed. In total we observed 193 bird species from 47 families. With the inclusion of Smithsonian Institution data from 2006, the bird species list for the Rewa Head rises to 250 from 54 families. These include 10 Guiana Shield endemics and two species recorded as rare throughout their ranges: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet