The Psittacine Year: Determinants of Annual Life History Patterns In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The International Parrotlet Society

steady and strong ever since. In the fall of 1992, several shipments The International Currently, the club has over 250 of captive-bred Spectacled Parrotlets members in three different countries. Forpus conspicillatus were imported Parrotlet Society Although most of the members are in the United States from Belgium. breeders, about 20 percent of the Due to their extremely limited num by Sandee Molenda members keep parrotlets as pets only. ber, the International Parrotlet Society Santa Cruz, California Each member receives a bi-monthly decided to sponsor a studbook to newsletter with articles written by ensure the continuing survival of this "'7";;e International Parrotlet Society breeders and pet owners on subjects species in the United States. As of l'i~ a non-profit bird club which is such as nutrition, identification of December 1993, 19 pairs and three dedicated to the breeding, main species and subspecies, breeding single males had been registered. At tenance, education, showing, conser methods, training techniques, hand least six pairs have produced offspring vation and keeping of parrotlets. feeding, banding, parrotlet psychol which are being traded among breed Although current members focus on ogy, color mutations and behavioral ers in order to maintain genetic birds from the genus Forpus, the problems. Members are also encour diversity. International Parrotlet Society also aged to submit individual questions The studbook is involved with the encourages the breeding ofthe genera and concerns in the Shorties column. International Species Inventory Sys Nannopsittaca and Touit. While other members most often tem founded by Dr. Ulysses S. Seal for The club was founded by Sandee respond, several veterinarians are the zoological community. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Population Size, Provisioning Frequency, Flock Size and Foraging

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Naturalis Population size, provisioning frequency, flock size and foraging range at the largest known colony of Psittaciformes: the Burrowing Parrots of the north-eastern Patagonian coastal cliffs Juan F. MaselloA,B,C,G, María Luján PagnossinD, Christina SommerE and Petra QuillfeldtF AInstitut für Ökologie, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany. BEcology of Vision Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, UK. CMax Planck Institute for Ornithology, Vogelwarte Radolfzell, Schlossallee 2, D-78315 Radolfzell, Germany. DFacultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina. EInstitut für Biologie/Verhaltensbiologie, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany. FSchool of Biosciences, Cardiff University, UK. GCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract.We here describe the largest colony of Burrowing Parrots (Cyanoliseus patagonus), located in Patagonia, Argentina. Counts during the 2001–02 breeding season showed that the colony extended along 9 km of a sandstone cliff facing the Altantic Ocean, in the province of Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina, and contained 51412 burrows, an estimated 37527 of which were active. To our knowledge, this is largest known colony of Psittaciformes. Additionally, 6500 Parrots not attending nestlings were found to be associated with the colony during the 2003–04 breeding season. We monitored activities at nests and movements between nesting and feeding areas. Nestlings were fed 3–6 times daily. Adults travelled in flocks of up to 263 Parrots to the feeding grounds in early mornings; later in the day, they flew in smaller flocks, making 1–4 trips to the feeding grounds. -

Illegal Trade of the Psittacidae in Venezuela

Illegal trade of the Psittacidae in Venezuela A DA S ÁNCHEZ-MERCADO,MARIANNE A SMÜSSEN,JON P AUL R ODRÍGUEZ L ISANDRO M ORAN,ARLENE C ARDOZO-URDANETA and L ORENA I SABEL M ORALES Abstract Illegal wildlife trade is one of the major threats to trade involves avian species, poached to supply both domes- Neotropical psittacids, with nearly % of species targeted tic and international demand for pets (Rosen & Smith, for the illegal pet trade. We analysed the most comprehen- ). Among birds, Neotropical psittacids are of primary sive data set on illegal wildlife trade currently available for conservation concern, with nearly % of species affected Venezuela, from various sources, to provide a quantitative by poaching for the illegal pet trade (Olah et al., ). assessment of the magnitude, scope and detectability of The data used to measure the magnitude of the illegal pet the trade in psittacids at the national level. We calculated trade in psittacids have come from four main sources: seiz- a specific offer index (SO) based on the frequency of ure records and surveys of trappers (Cantú Guzmán et al., which each species was offered for sale. Forty-seven species ), literature reviews (Pires, ; Alves et al., ), dir- of psittacids were traded in Venezuela during –,of ect observation in markets (Herrera & Hennessey, ; which were non-native. At least , individuals were Gastañaga et al., ; Silva Regueira & Bernard, ), traded, with an overall extraction rate of , individuals and observation of the proportion of nest cavities poached per year ( years of accumulated reports). Amazona (Wright et al., ; Pain et al., ; Zager et al., ). ochrocephala was the most frequently detected species Each source has a unique geographical and taxonomic (SO = .), with the highest extraction rate (, indivi- coverage and evaluates different aspects of the market duals per year), followed by Eupsittula pertinax (SO = .) chain. -

Rødbrystet Conure

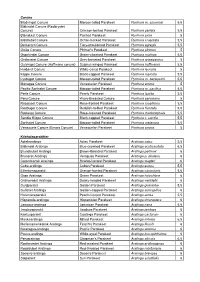

Conure Blodvinget Conure Maroon -tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. souancei 5,5 Blåkindet Conure (Rødbrystet Conure) Crimson-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura perlata 5,5 Blånakket Conure Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta 5 Blåstrubet Conure Ochre-marked Parakeet Pyrrhura cruentata 5,5 Demerara Conure Fiery-shouldered Parakeet Pyrrhura egregia 5,5 Goiás Conure Pfrimer's Parakeet Pyrrhura pfrimeri 5 Grønkindet Conure Green-cheeked Parakeet Pyrrhura molinae 5,5 Gråbrystet Conure Grey-breasted Parakeet Pyrrhura griseipectus 5 Gulvinget Conure (Hoffmans conure) Sulphur-winged Parakeet Pyrrhura hoffmanni 5,5 Hvidøret Conure White-eared Parakeet Pyrrhura leucotis 5 Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura rupicola 5,5 Lysbuget Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. berlepschi 5,5 Monagas Conure Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Pacific Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. pacifica 5,5 Perle Conure Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida 5,5 Peru Conure Wavy-Breasted Conure Pyrrhura peruviana 5 Rosaisset Conure Rose-fronted Parakeet Pyrrhura roseifrons 5,5 Rødbuget Conure Reddish-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura frontalis 5,5 Rødisset Conure Rose-crowned Parakeet Pyrrhura rhodocephala 5,5 Sandia Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura r. sandia 5,5 Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura melanura 5,5 Venezuela Conure (Emma Conure) Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Kilehaleparakitter Aztekaratinga Aztec Parakeet Aratinga astec 5,5 Blåkindet Aratinga Blue-crowned Parakeet Aratinga acuticaudata 6,5 Brunstrubet Aratinga Brown-throated Parakeet -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Two Endangered Neotropical Parrots Inform in Situ and Ex Situ Conservation Strategies

diversity Article Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Two Endangered Neotropical Parrots Inform In Situ and Ex Situ Conservation Strategies Carlos I. Campos 1 , Melinda A. Martinez 1, Daniel Acosta 1, Jose A. Diaz-Luque 2, Igor Berkunsky 3 , Nadine L. Lamberski 4, Javier Cruz-Nieto 5 , Michael A. Russello 6 and Timothy F. Wright 1,* 1 Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] (C.I.C.); [email protected] (M.A.M.); [email protected] (D.A.) 2 Fundación CLB (FPCILB), Estación Argentina, Calle Fermín Rivero 3460, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia; [email protected] 3 Instituto Multidisciplinario sobre Ecosistemas y Desarrollo Sustenable, CONICET-Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Tandil 7000, Argentina; [email protected] 4 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, San Diego, CA 92027, USA; [email protected] 5 Organización Vida Silvestre A.C. (OVIS), San Pedro Garza Garciá 66260, Mexico; [email protected] 6 Department of Biology, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A key aspect in the conservation of endangered populations is understanding patterns of Citation: Campos, C.I.; Martinez, genetic variation and structure, which can provide managers with critical information to support M.A.; Acosta, D.; Diaz-Luque, J.A.; evidence-based status assessments and management strategies. This is especially important for Berkunsky, I.; Lamberski, N.L.; species with small wild and larger captive populations, as found in many endangered parrots. We Cruz-Nieto, J.; Russello, M.A.; Wright, used genotypic data to assess genetic variation and structure in wild and captive populations of T.F. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

Birds of Brazil

BIRDS OF BRAZIL - MP3 SOUND COLLECTION version 2.0 List of recordings 0001 1 Greater Rhea 1 Song 0:17 Rhea americana (20/7/2005, Chapada dos Guimaraes, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 15.20S,55.50W) © Peter Boesman 0006 1 Gray Tinamou 1 Song 0:43 Tinamus tao (15/8/2007 18:30h, Nirgua area, San Felipe, Venezuela, 10.15N,68.30W) © Peter Boesman 0006 2 Gray Tinamou 2 Song 0:24 Tinamus tao (2/1/2008 17:15h, Tarapoto tunnel road, San Martín, Peru, 06.25S,76.15W) © Peter Boesman 0006 3 Gray Tinamou 3 Whistle 0:09 Tinamus tao (15/8/2007 18:30h, Nirgua area, San Felipe, Venezuela, 10.15N,68.30W) © Peter Boesman 0007 1 Solitary Tinamou 1 Song () 0:05 Tinamus solitarius (11/8/2004 08:00h, Serra da Graciosa, Paraná, Brazil, 25.20S,48.55W) © Peter Boesman. 0009 1 Great Tinamou 1 Song 1:31 Tinamus major (3/1/2008 18:45h, Morro de Calzada, San Martín, Peru, 06.00S,77.05W) © Peter Boesman 0009 2 Great Tinamou 2 Song 0:31 Tinamus major (28/7/2009 18:00h, Pantiacolla Lodge, Madre de Dios, Peru, 12.39S,71.14W) © Peter Boesman 0009 3 Great Tinamou 3 Song 0:27 Tinamus major (26/7/2009 17:00h, Pantiacolla Lodge, Madre de Dios, Peru, 12.39S,71.14W) © Peter Boesman 0009 4 Great Tinamou 4 Song 0:46 Tinamus major (22nd July 2010 17h00, ACTS Explornapo, Loreto, Peru, 120 m. 3°10' S, 72°55' W). (Background: Thrush-like Antpitta, Elegant Woodcreeper). © Peter Boesman. 0009 5 Great Tinamou 5 Call 0:11 Tinamus major (17/7/2006 17:30h, Iracema falls, Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas, Brazil, 02.00S,60.00W) © Peter Boesman.