What Eats Parrots?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

Priority Contribution Quantifying the Illegal Parrot Trade in Santa Cruz De La Sierra, Bolivia, with Emphasis on Threatened Spec

Bird Conservation International (2007) 17:295–300. ß BirdLife International 2007 doi: 10.1017/S0959270907000858 Printed in the United Kingdom Priority contribution Quantifying the illegal parrot trade in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, with emphasis on threatened species MAURICIO HERRERA HURTADO and BENNETT HENNESSEY Summary We monitored the illegal pet trade in Los Pozos pet market from August 2004 to July 2005. As indicated in Bolivian law, all unauthorized trade in wild animal species is illegal, especially species considered threatened by IUCN. During this period, we recorded 7,279 individuals of 31 parrot species, including four threatened species, two of which were being transported from Brazil through Bolivia to markets in Peru. The most frequently sold species was the Blue-fronted Parrot Amazona aestiva with 1,468 individuals observed during our study, the majority of which (94%) were believed to have been captured in the wild. Most of the purchased birds remain within Bolivia, while the more expensive, threatened species frequently head to Peru; some individuals may even reach Europe. We believe our study describes only a small proportion of the Bolivian parrot trade, underscoring the potential extent of the illegal pet trade and the need for better Bolivian law enforcement. Resumen Monitoreamos el comercio ilegal de aves en el mercado de mascotas de Los Pozos, desde agosto de 2004 a julio de 2005. De acuerdo a lo que establece la ley boliviana, todo comercio no autorizado de animales salvajes es ilegal, especialmente de especies consideradas Amenazadas por la IUCN. Durante este periodo, grabamos 7.279 individuos de 31 especies de loros, incluyendo 4 especies amenazadas, de las cuales dos fueron transportadas desde Brasil a trave´s de Bolivia hacia mercados en Peru´ . -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Rødbrystet Conure

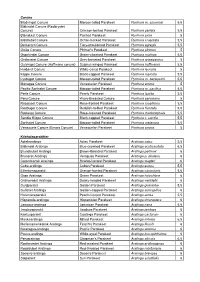

Conure Blodvinget Conure Maroon -tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. souancei 5,5 Blåkindet Conure (Rødbrystet Conure) Crimson-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura perlata 5,5 Blånakket Conure Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta 5 Blåstrubet Conure Ochre-marked Parakeet Pyrrhura cruentata 5,5 Demerara Conure Fiery-shouldered Parakeet Pyrrhura egregia 5,5 Goiás Conure Pfrimer's Parakeet Pyrrhura pfrimeri 5 Grønkindet Conure Green-cheeked Parakeet Pyrrhura molinae 5,5 Gråbrystet Conure Grey-breasted Parakeet Pyrrhura griseipectus 5 Gulvinget Conure (Hoffmans conure) Sulphur-winged Parakeet Pyrrhura hoffmanni 5,5 Hvidøret Conure White-eared Parakeet Pyrrhura leucotis 5 Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura rupicola 5,5 Lysbuget Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. berlepschi 5,5 Monagas Conure Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Pacific Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. pacifica 5,5 Perle Conure Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida 5,5 Peru Conure Wavy-Breasted Conure Pyrrhura peruviana 5 Rosaisset Conure Rose-fronted Parakeet Pyrrhura roseifrons 5,5 Rødbuget Conure Reddish-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura frontalis 5,5 Rødisset Conure Rose-crowned Parakeet Pyrrhura rhodocephala 5,5 Sandia Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura r. sandia 5,5 Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura melanura 5,5 Venezuela Conure (Emma Conure) Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Kilehaleparakitter Aztekaratinga Aztec Parakeet Aratinga astec 5,5 Blåkindet Aratinga Blue-crowned Parakeet Aratinga acuticaudata 6,5 Brunstrubet Aratinga Brown-throated Parakeet -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Massive Seed Predation of Pseudobombax Grandiflorum (Bombacaceae) by Parakeets Brotogeris Versicolurus (Psittacidae) in a Forest Fragment in Brazil’

Notes 613 BlOTROPlCA 34(4): 613-615 2002 Massive Seed Predation of Pseudobombax grandiflorum (Bombacaceae) by Parakeets Brotogeris versicolurus (Psittacidae) in a Forest Fragment in Brazil’ ABSTRACT Here we report massive seed predation of Pseudobombax grandzfirum (Bombacaceae) by Botogeris versicolurus (Psitta- cidae) in a forest fragment in Brazil. The intensity of seed predation was very high when compared to other studies in continuous forest, perhaps resulting from a scarcity of resources in such areas. This scarcity may limit the range of parrot’s diet to a few plant species. It suggests that studies of Psittacidae seed predation may be important for con- servation of some plants in fragments. Kq word: Atlantic Forest; Brazil; Brotogeris versicolurus; firest papentation; Pseudobombax grandiflorum; Psitta- riake; seed preaktion. A SUBSTANTIAL PORTION OF SEED CROP is lost to predators in every fruiting event Uanzen 1972, 1981; Howe 1980; Schupp 1988) and because of this extensive mortality, seed predation is one of the major ecological and evolutionary forces affecting individual plants, populations, and communities (Schupp 1988). Psittacids (parrots, macaws, and parakeets) have been recognized as important pre-dispersal seed predators in the Neotropics Uanzen 1972, Higgins 1979, Howe 1980, Janzen 1981, Galetti & Rodrigues 1992, Coates-Estrada et al. 1993). The diet of most species consists of fruits, seeds, and flowers, which are taken in treetops or on the ground (Forshaw 1981, Roth 1984, Galetti 1993); however, despite their potential impacts on plant recruitment, very few data are available on the intensity of seed predation by parrots, especially in fragmented forests (Higgins 1979, Galetti & Rodrigues 1992). The Canary-winged Parakeet Brotogeris uersicolurw is a small, long-tailed psittacid that is widely distributed in South America. -

Brotogeris Jugularis) in Costa Rica

October 1981] Short Communications 841 appreciable residuesof pollutants may be present. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) have been found on the surface of polystyrene spherules, apparently absorbed from seawater, in a concentration of five parts per million (Carpenter et al. 1972), and it may be assumedthat organochlorinesare associatedwith other oceanic plastic items. Measurable residuesof DDT, DDE, and PCBs were detected in visceral fat from Black-footed and Laysan albatross on Midway (Fisher 1973). Although the origin of such ingested pol- lutants may be in the North Pacific food chain, it may also be associated with plastics ingested by albatross. Our stay on Midway Islands was supported by a National Science Foundation Grant (PCM 12351- A01) administeredby Dr. G. C. Whittow. We are grateful to CDR Kuhneman, Commanding Officer, for assistanceduring our stay at the U.S. Naval Air Facility, Midway Island. Special thanks to ENS Immel and the base game warden staff for invaluable aid and transportation to Eastern Island. We thank Elizabeth Flint, Department of Biology, U.C.L.A., for collecting fresh castingson French Frigate Shoals and G. H. Balazs for the use of unpublished data. We also thank Craig Harrison for his critical review of the manuscript. LITERATUIIE CITED CAIIPENTEII, E. J., S. J. ANDEIISON, G. R. HAlIVEY, H. P. MIKLAS, & B. B. PECK. 1972. Polystyrene spherules in coastal waters. Science 178: 749-750. DAY, R. H. 1980. The occurrence and characteristics of plastic pollution in Alaska's marine birds. Unpublished M.S. thesis, College, Alaska, Univ. Alaska. FISHEli, H. [. 1973. Pollutants in North Pacific albatrosses.Pacific Sci. 27; 220-225. -

Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 Under the Biosecurity Act 2015

New South Wales Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 His Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Biosecurity Act 2015. NIALL BLAIR, MLC Minister for Primary Industries Explanatory note The objects of this Regulation are: (a) to update the lists of pests and diseases of plants, pests and diseases of animals, diseases of aquatic animals, pest marine and freshwater finfish and pest marine invertebrates (set out in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Act)) that are prohibited matter throughout the State, and (b) to update the description (set out in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Act) of the part of the State in which Daktulosphaira vitifoliae (Grapevine phylloxera) is a prohibited matter, and (c) to include (in Schedule 3 to the Act) lists of non-indigenous amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles in respect of which dealings are prohibited or permitted, and (d) to provide (in Schedule 4 to the Act) that certain dealings with bees and certain non-indigenous animals require biosecurity registration, and (e) to update savings and transitional provisions with respect to existing licences (in Schedule 7 to the Act). This Regulation is made under the Biosecurity Act 2015, including sections 27 (4), 151 (2), 153 (2) and 404 (the general regulation-making power) and clause 1 (1) and (5) of Schedule 7. Published LW 2 June 2017 (2017 No 230) Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 [NSW] Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 1 Name of Regulation This Regulation is the Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017.