The Development of Informal Settlements in South Africa, with Particular Reference to Informal Settlements Around Daveyton on the East Rand, 19704999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Branch Lectures & Events

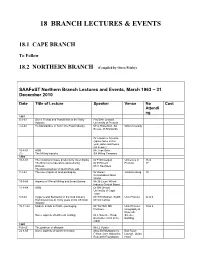

18 BRANCH LECTURES & EVENTS 18.1 CAPE BRANCH To Follow 18.2 NORTHERN BRANCH (Compiled by Owen Frisby) SAAFoST Northern Branch Lectures and Events, March 1963 – 31 December 2010 Date Title of Lecture Speaker Venue No Cost Attendi ng 1963 5-3-63 Some Trends and Possibilities in the Dairy Prof SH Lombard. Industry University of Pretoria 2-4-63 To Standardise or Not in the Food Industry Mr G Robertson. SA Wits University Bureau of Standards Dr Lawrence Novellie (spoke twice in this year, dates and topics not known) 15-8-63 AGM Mr J van Selm. (?) The Milling Industry SA Milling Company 1964 10-3-64 The cooking of maize products by roller drying Dr F Schweigart University of 16 & The Birs low-temperature spray-drying Dr E Rickert Pretoria 17 process. Mr C Saunders The pasteurization of liquid whole egg. 7-4-64 The use of glass in food packaging Dr Donen. Johannesburg 10 Consolidated Glass Works 19-5-64 Aspects of Wheat Milling and Bread Baking Mr JB Louw. Wheat Industry Control Board 11-8-64 AGM Dr GN Dreosti University of Cape Town 8-9-64 Hygiene and Sanitation in the food industry Mr WR Mottram. SABS Univ Pretoria 22 & 6 Reminiscences of thirty years in the UK food Mr VA Cachia industry 10-11-64 Modern trends in flexible packaging. Mr TG Hutt. MD Univ Pretoria: 19 & 6 Packsure Geography & Domestic Some aspects of kaffircorn malting Dr L Novellie. Head, Science Bantu Beer Unit of the Building CSIR 1965 Feb-65 The problem of aflatoxin Mr LJ Vorster 22-6-65 Some aspects of starch chemistry. -

Gauteng Gauteng

Gauteng Gauteng Thousands of visitors to South Africa make Gauteng their first stop, but most don’t stay long enough to appreciate all it has in store. They’re missing out. With two vibrant cities, Johannesburg and Tshwane (Pretoria), and a hinterland stuffed with cultural treasures, there’s a great deal more to this province than Jo’burg Striking gold International Airport, says John Malathronas. “The golf course was created in 1974,” said in Pimville, Soweto, and the fact that ‘anyone’ the manager. “Eighteen holes, par 72.” could become a member of the previously black- It was a Monday afternoon and the tees only Soweto Country Club, was spoken with due were relatively quiet: fewer than a dozen people satisfaction. I looked around. Some fairways were in the heart of were swinging their clubs among the greens. overgrown and others so dried up it was difficult to “We now have 190 full-time members,” my host tell the bunkers from the greens. Still, the advent went on. “It costs 350 rand per year to join for of a fully-functioning golf course, an oasis of the first year and 250 rand per year afterwards. tranquillity in the noisy, bustling township, was, But day membership costs 60 rand only. Of indeed, an achievement of which to be proud. course, now anyone can become a member.” Thirty years after the Soweto schoolboys South Africa This last sentence hit home. I was, after all, rebelled against the apartheid regime and carved ll 40 Travel Africa Travel Africa 41 ERIC NATHAN / ALAMY NATHAN ERIC Gauteng Gauteng LERATO MADUNA / REUTERS LERATO its name into the annals of modern history, the The seeping transformation township’s predicament can be summed up by Tswaing the word I kept hearing during my time there: of Jo’burg is taking visitors by R511 Crater ‘upgraded’. -

South Africa's Xenophobic Eruption

South Africa’s Xenophobic Eruption INTRODUCTION We also visited two informal settlements in Ekhuruleni: Jerusalem and Ramaphosa. In Ramaphosa, Between 11 and 26 May 2008, 62 people, the major- the violence was sustained and severe. At time of writing, ity of them foreign nationals, were killed by mobs in four months to the day aft er the start of the riots, not a Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and elsewhere. Some single foreign national has returned.2 In Jerusalem, in 35,000 were driven from their homes.1 An untold number contrast, the violence, although severe, lasted a single of shacks were burnt to the ground. Th e troubles were night, before it was quelled by police and residents. Our dubbed South Africa’s ‘xenophobic riots’. Th ey constitute visits to these sites were particularly fruitful inasmuch as the fi rst sustained, nationwide eruption of social unrest we were able to conduct six reasonably intensive inter- since the beginning of South Africa’s democratic era views with young men who claimed to have joined the in 1994. mobs and participated in the violence. Between 1 and 10 June, in the immediate aft ermath Th e fi rst section of this paper recounts at some length of the riots, I, together with the photojournalist Brent the experience of a single victim of the xenophobic vio- Stirton, visited several sites of violence in the greater lence in South Africa, a Mozambican national by the name Johannesburg area. In all we interviewed about 110 of Benny Sithole. Th e second section explores the genesis people. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Profile: City of Ekurhuleni

2 PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction: Brief Overview............................................................................. 6 2.1 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................... 6 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Spatial Integration ................................................................................................. 8 3. Social Development Profile............................................................................... 9 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 12 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 13 3.4 Poverty Dimensions ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Distribution .......................................................................................................... 15 3.4.2 Inequality ............................................................................................................. 16 3.4.3 Employment/Unemployment -

ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES and WASTE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT IWMSA SEMINAR STATUS QUO: WASTE MANAGEMENT in the Coe

ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES AND WASTE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT IWMSA SEMINAR STATUS QUO: WASTE MANAGEMENT IN THE CoE MJ MAGOLELA 1 TABLE OF CONTENT • The Integrated Waste Management Plan • Defining the geographical area • Demographic comparison of municipalities • Treatment and disposal • Available Airspace • Service area and estimated waste received per day • Waste received from outside City of Ekurhuleni • Percentage of different waste types disposed at the City of Ekurhuleni landfills • Waste generation percentage in total tonnage by income groups • Mini Waste Disposal facilities • Waste Recycling • Projection of monthly waste and recyclables for residential areas in the City of Ekurhuleni • Challenges for the City of Ekurhuleni • IWMP Goals • 5 Implementation Instruments • 6. Implementation planning Geographical Area Description • Situated in the Eastern region of the Gauteng Province and bordered by the metropolitan municipalities of Johannesburg and Tshwane. • The City spreads over 15.6% of Gauteng’s land mass equivalent of 1,975km2. • It is the fourth largest of the eight metropolitan areas in the country established as a metro in 2000 consists of nine towns namely Alberton, Benoni, Boksburg, Brakpan, Edenvale, Germiston, Kempton Park, Nigel, Springs and 17 townships. • There are 112 wards with 20 customer care centers and 10 waste management depots spread across the land mass of the City. • There is over 125 informal settlements spread across the CCC management areas. • The City is home to 3.38 million people with Ekurhuleni's rate of -

2021/26 Draft IDP

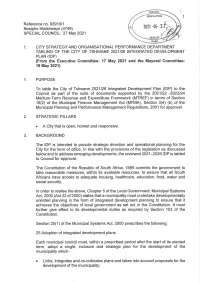

ANNEXURE A 16 Annexure A CITY OF TSHWANE 2021-2026 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN MAY 2021 o 1 17 CONTENTS PREAMBLE: 2021–2026 DRAFT INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN ............... 3 1 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ................................................................................. 9 2 STRATEGIC INTENT ........................................................................................ 53 3 GOVERNANCE AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ............................ 92 4 INTER-GOVERNMENTAL ALIGNMENT .......................................................... 63 5 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION ...................................................................... 86 6 METROPOLITAN SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK ........................ 94 7. CAPITAL EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK ..................................................... 117 8 KEY DELIVERABLES FOR 2021/22 – 2025/26 ............................................. 162 9 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT ................................................................. 170 10 CITY OF TSHWANE DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN .............................. 188 11 FINANCIAL PLAN .......................................................................................... 208 o 2 18 PREAMBLE: 2021–2026 DRAFT INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN Introduction On the 20th August 2020, the Council adopted the 2021-26 Integrated Development Plan Process Plan. The IDP Process plan has set the strategic pillars and deliverables to guide the City on a new development trajectory which aims to create: a city of opportunity; a sustainable city; -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

A Case Study of the Ivory Park Community Work Programme

A CASE STUDY OF THE IVORY PARK COMMUNITY WORK PROGRAMME Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) study on the Community Work Programme (CWP) Themba Masuku – Senior Researcher August 2015 Acknowledgements This report is based on research carried out in Ivory Park in 2014. I would like to thank the many people, including staff and participants within the Community Work Programme and others, who contributed to the research by participating in interviews and focus groups and in other ways. The research was also supported by feedback from members of the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Urban Violence Study Group, including Hugo van der Merwe, Malose Langa, Jasmina Brankovic, Kindisa Ngubeni and David Bruce. Many others at CSVR also assisted with this work in one way or another. David Bruce assisted with the editing of the report. © September 2015, Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 3rd Floor, Forum V, Braampark Office Park, 33 Hoofd Street, Braamfontein P O Box 30778, Braamfontein, 2017, South Africa; Tel: (011) 403-5650. Fax: (011) 388-0819. Email: [email protected]. CSVR website: http://www.csvr.org.za This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government’s Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. International Development Research Centre Centre de recherches pour le développement international Table of Contents Introduction -

10-Thembisa Waetjen-Ok.Pmd

Man In India, 93 (4) : 627-643 © Serials Publications FAHMIDA’S WORLDS: GENDER, HOME AND THE GUJARATI MUSLIM DIASPORA IN MID-20TH CENTURY SOUTH AFRICA Thembisa Waetjen This paper focuses on the journalistic writing of Zuleikha Mayat, a housewife living in Durban, South Africa who wrote a weekly column for the newspaper Indian Views between 1956 and 1963. It explores how this body of work drew upon, and constructed, conceptions of belonging and unsettlement in relation to political and customary practices shaping the lives of Muslim women within her diasporic and class milieu. Through opinion, commentary, historical narrative and allegorical fiction, her published writings moralised an ideal of the ‘domestic’ to bridge the worlds of household and nation as domains of action and concern. Falling within a period of expanding apartheid legislation, when the state abandoned its determined push for the ‘repatriation’ of ‘Asiatics’ to instead incorporate ‘Indians’ as a unitary racial group through a specialized political bureaucratic structure, the column ‘Fahmida’s World’ can be seen as an endeavour to imagine conceptions of belonging, home and identity for her readership and to grapple with political exclusion. Keywords: Gujarati, Muslim, South Africa, Indian, Identity, Politics, Resistance Introduction From 1956-1963 Durban housewife and community organizer, Zuleikha Mayat, wrote a regular column for the Gujarati/English language South African newspaper Indian Views. With a readership that extended from the Cape to Mozambique and trickled northward as far as Malawi, the weekly (later bi-weekly) Indian Views covered news on both shores of the Indian Ocean and helped to reproduce a communal imaginary for Gujarati-speaking Muslims in early-mid 20th century southern Africa. -

R50 Realignment Draft Environmental Impact Report

63 Wessel Road, Rivonia, 2128 PO Box 2597, Rivonia, 2128 South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 803 5726 Fax: +27 (0) 11 803 5745 Web: www.gcs-sa.biz R50 Road Realignment Draft Environmental Impact Assessment Report MDARDLEA ref: 1/3/1/16/1N-47 Version – Draft for Public and Authority Review 21 September 2016– 21 October 2016 Exxaro Leeuwpan GCS Project Number: 15-070 Client Reference: R50 Road Realignment GCS (Pty) Ltd. Reg No: 2004/000765/07 Est. 1987 Offices: Durban Johannesburg Lusaka Ostrava Pretoria Windhoek Directors: AC Johnstone (Managing) PF Labuschagne AWC Marais S Pilane (HR) W Sherriff (Financial) www.gcs-sa.biz Non-Executive Director: B Wilson-Jones Exxaro Leeuwpan R50 Road Realignment Report Version – Draft for Public and Authority Review 21 September 2016– 21 October 2016 Exxaro Leeuwpan 15-070 DOCUMENT ISSUE STATUS Report Issue Draft for public and authority review GCS Reference Number GCS Ref - 15-070 Client Reference R50 Road Realignment Title R50 Road Realignment Draft Environmental Impact Assessment Report Name Signature Date Matthew Muller Author 21 September 2016 Samantha Munro Document Reviewer Riana Panaino 21 September 2016 Renee Janse van Unit Manager 21 September 2016 Rensburg Director Pieter Labuschagne 21 September 2016 LEGAL NOTICE This report or any proportion thereof and any associated documentation remain the property of GCS until the mandatory effects payment of all fees and disbursements due to GCS in terms of the GCS Conditions of Contract and Project Acceptance Form. Notwithstanding the aforesaid, any reproduction, duplication, copying, adaptation, editing, change, disclosure, publication, distribution, incorporation, modification, lending, transfer, sending, delivering, serving or broadcasting must be authorised in writing by GCS. -

R13.08 47 028 868 28 R42.79 10 862 035 42

1/11/2021 All Meat Trade Overview SAPPO Trade Report South African Meat Trade Overview November 2020 R42.79 10 862 035 42 Avg. Export Price (R/Kg) Export Volume (Kg) Export Countries R13.08 47 028 868 28 Import Countries Avg. Import Price (R/Kg) Import Volume (Kg) Export Quantity by Livestock Type (Kg) Export Price by Livestock Type (R/Kg) Bovine 4 258 155 Bovine R60.55 Lamb/Sheep 216 774 Lamb/Sheep R105.09 Poultry 5 242 645 Poultry R25.59 Swine 1 144 461 Swine R43.67 0K 5 000K R0 R50 R100 Import Quantity by Livestock Type (Kg) Import Price by Livestock Type (R/Kg) Bovine 3 617 445 Bovine R15.37 Lamb/Sheep 140 226 Lamb/Sheep R29.50 Poultry 40 732 840 Poultry R11.08 Swine 2 538 357 Swine R40.94 0K 20 000K 40 000K R0 R20 R40 Page 1 1/1 1/11/2021 All Meat Exports SAPPO Trade Report South African Meat Trade Exports November 2020 Export Quantity ('000 Kg) Bovine Lamb/Sheep Poultry Swine 8 000K 7 859.5K 6 789.1K 6 519.6K 5 975.7K 6 463.9K 6 000K 5 242.6K 5 658.7K 4 727.2K 4 445.1K 4 393.0K 4 258.2K 4 000K 4 078.8K 3 678.9K 3 309.8K 3 295.6K 1 834.4K 2 000K 2 186.7K 1 474.6K 715.5K 1 155.5K 216.8K 832.7K 151.1K 17.8K 179.7K 49.5K 36.8K 80.9K 0K 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Export Price (R/Kg) Bovine Lamb/Sheep Poultry Swine R135.24 R105.09 R100 R87.08 R78.18 R76.61 R60.77 R56.45 R60.55 R50 R39.56 R49.84 R46.50 R29.52 R29.49 R40.28 R26.47 R39.66 R25.59 R19.51 R32.16 R30.98 R27.19 R29.21 R20.48 R19.60 R0 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Products included HS4 Tariff Code Meat Type Description 0201-0202 Beef Meat of bovine animals, fresh, chilled or frozen 0203, 0210, 16024 Pork Meat of swine, fresh, chilled or frozen; Other prepared or preserved meat; Meat and edible meat offal 0204 Lamb Meat of sheep or goats, fresh, chilled or frozen 0207 Poultry Meat and edible offal of fowls of the species Gallus domesticus, ducks, geese and turkeys Page 2 1/1 1/11/2021 All Meat Imports SAPPO Trade Report South African Meat Trade Imports November 2020 Import Quantity ('000 Kg) Import Quantity excl.