Gothic Art and Architecture in 15Th-Century Castile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Sepulcros Del Cardenal Fray García De Loaysa Y Sus Padres En

AEA, LXXVI, 2003, 303, pp. 267 a 276. ISSN: 0004-0428 LOS SEPULCROS DEL CARDENAL FRAY GARCIA DE LOAYSA Y SUS PADRES EN EL MONASTERIO DOMINICO DE TALAVERA DE LA REINA * POR JUAN NICOLAO CASTRO Doctor por la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Se estudian los sepulcros D. Pedro Loaysa y de su esposa Dña. Catalina de Mendoza, así como el de su hijo el Cardenal Fray García de Loaysa. Se conservan en el antiguo monasterio dominico de San Ginés de Talavera de la Reina. Se atribuyen al taller de Bigarny los dos primeros y al de Gregorio Pardo, quizá termi nando la obra del padre, el último. Palabras clave: Sepulcros. Escultura S. xvi. Pedro de Loaysa. Catalina de Mendoza. García de Loaysa. Convento de San Ginés.Talavera de la Reina. Bigarny. Gregorio Pardo. This is a study of the tombs of D. Pedro Loaysa and his wife Dña. Catalina de Mendoza, as well as that of their son, Cardinal Friar Garcia de Loaysa. They are preserved in the old Dominican monastery of San Ginés in Talavera de la Reina. The first two are attributed to the workshop of Bigarny and the third to that of Gregorio Pardo. Key words: Tombs. Sculpture. Sixteenth century. Pedro de Loaysa. Catalina de Mendoza. García de Loaysa. Convent of San Ginés. Talavera de la Reina. Bigarny. Gregorio Pardo. El monasterio dominico de San Ginés de Talavera de la Reina fue una víctima más de la desamortización del s. xix, vendiéndose su edificio, que quedó convertido en fábrica de tina jas. De su antiguo esplendor es poco lo conservado, la arquitectura de la iglesia y el claustro, y de su decoración sólo han permanecido «in situ» los sepulcros de D. -

El Museo Nacional Colegio De San Gregorio

Revista Museos 08 29/9/08 15:20 Página 56 Enrique Sobejano1 El Museo Nacional Fuensanta Nieto Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos S.L. Madrid Colegio de San Gregorio (Valladolid)2 Enrique Sobejano y Fuensanta Nieto son Resumen: El artículo describe las inter- cuencia, la imagen del arquitecto como Arquitectos titulados por la Escuela Técnica venciones arquitectónicas llevadas a cabo autor y único responsable intelectual de la Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid y por la en el Colegio de San Gregorio, construido obra se pone en cuestión cuando se trata, Universidad de Columbia de Nueva York y socios fundadores de Nieto Sobejano en el siglo XV y, desde 1932, sede del como en este caso, de ampliar un edificio Arquitectos. Entre 1986 y 1991 fueron Museo Nacional Colegio de San Gregorio. ya existente, concebido en otra época por directores de la revista Arquitectura editada Recoge las ideas y el proceso seguido des- otros arquitectos y transformado notable- por el Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de de el punto de vista de los arquitectos mente a lo largo de los siglos. Difícilmente Madrid. Asimismo han realizado numerosos proyectos arquitectónicos por autores del proyecto de rehabilitación y se comprendería que un artista modificara los que han sido galardonados con diversos ampliación. una obra ajena en el campo de la música, premios y distinciones entre los que la pintura, la escultura, la literatura o el destaca el Premio Nacional de Palabras clave: Transformación, Historia, cine; sin embargo, la arquitectura asume Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales, recibido en 2007 por el proyecto Museo, Estructura formal, Rehabilitación, por naturaleza la posibilidad de su trans- arquitectónico del Museo Nacional de Arquitectura de museos, Proyecto arqui- formación, en un continuo proceso de Escultura (Valladolid). -

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Dandelet, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Ignacio E. Navarrete Summer 2015 The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance, and Morisco Identity © 2015 by Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry All Rights Reserved The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California-Berkeley Thomas Dandelet, Chair Abstract In the Spanish city of Granada, beginning with its conquest by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, Christian aesthetics, briefly Gothic, and then classical were imposed on the landscape. There, the revival of classical Roman culture took place against the backdrop of Islamic civilization. The Renaissance was brought to the city by its conquerors along with Christianity and Castilian law. When Granada fell, many Muslim leaders fled to North Africa. Other elite families stayed, collaborated with the new rulers and began to promote this new classical culture. The Granada Venegas were one of the families that stayed, and participated in the Renaissance in Granada by sponsoring a group of writers and poets, and they served the crown in various military capacities. They were royal, having descended from a Sultan who had ruled Granada in 1431. Cidi Yahya Al Nayar, the heir to this family, converted to Christianity prior to the conquest. Thus he was one of the Morisco elites most respected by the conquerors. -

Monumental Entornos Monumentales Y Edificios Históricos

Monumental Entornos monumentales y edificios históricos. The historic sites and buildings. Zones monumentales et passe devant des bâtiments. ¡La Historia! Palacio de Pimentel 2 Valladolid Monumental Este paseo por Valladolid transcurre Visitaremos palacios y casonas de por entornos monumentales y edificios importancia relevante en la vida de históricos, ofreciendo un auténtico viaje una ciudad que, como Valladolid, fue a través del tiempo: Plaza Mayor, Palacio corte de España durante muchos años de Santa Cruz, Universidad, Catedral, y en ella vivieron personajes del mundo plaza de San Pablo, Museo Nacional de las artes y de las letras de renombre de Escultura, Palacio Real, Palacio de universal. Pimentel, etc. A lo largo de la alta Edad Media y principios de la Edad Moderna la entonces villa de Valladolid fue en múltiples ocasiones asiento de la corte itinerante y aquí estaba la Real Audiencia y Chancillería. This tours runs trouhg the historic sites We will visit palaces and manor houses and buildings of Valladolid offering a of great importance in the life of a real journey through time: Santa Cruz city which, as in case of Valladolid, was Palace, the University, the Cathedral, Spain’s Court for many years and which San Pablo square, the National Museum was home to universally famous people of Sculpture, Royal Palace, “Palace” of of the arts and letters world. Pimentel ,etc. During the late middle ages and the beginning of the modern era, the then called Villa de Valladolid on many occasions played host to the itinerant court and this was where the Royal Court and Chancery were located. -

El Testamento Del Obispo Alonso De Burgos: Religiosidad, Construcción De La Memoria Y Preeminencia Eclesiástica En Castilla a Fines Del Siglo XV

Díaz Ibáñez, Jorge El testamento del obispo Alonso de Burgos: religiosidad, construcción de la memoria y preeminencia eclesiástica en Castilla a fines del siglo XV Estudios de Historia de España Vol. XIX, 2017 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Díaz Ibáñez, Jorge. “El testamento del obispo Alonso de Burgos : religiosidad, construcción de la memoria y preeminencia eclesiástica en Castilla a fines del siglo XV” [en línea], Estudios de Historia de España 19 (2017). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/testamento-obispo-alonso-burgos-castilla.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 04 Ibañez testamento_Maquetación 1 27/11/2017 10:07 a.m. Página 103 EL TESTAMENTO DEL OBISPO ALONSO DE BURGOS: RELIGIOSIDAD, CONSTRUCCIÓN DE LA MEMORIA Y PREEMINENCIA ECLESIÁSTICA EN CASTILLA A FINES DEL SIGLO XV* THE WILL OF BISHOP ALONSO DE BURGOS: RELIGIOUS BELIEF, MEMORY AND ECCLESIASTICAL PROMINENCE IN CASTILIAN KINGDOM AT THE END OF XV CENTURY OBISPO ALONSO DE BURGOS PERANTE A MORTE: RELIGIOSIDADE, CONSTRUÇÃO DA MEMÓRIA E PREEMINÊNCIA ECLESIÁSTICA EM CASTELA NOS FINAIS DO SÉCULO XV JORGE DÍAZ IBÁÑEZ** Universidad Complutense de Madrid Resumen En el presente trabajo se realiza un análisis y edición del testamento otorgado en 1499 por el entonces obispo palentino Alonso de Burgos, personaje muy vinculado a los Reyes Católicos durante décadas y fundador del colegio de San Gregorio de Valla- dolid. -

Convall2016.Pdf

Conocer Valladolid 2016 Este volumen reúne las contribuciones científicas presentadas en el X Curso Conocer Valladolid, celebrado en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de la Purísima Concepción de Valladolid, entre los días 7 y 30 de noviembre del año 2016. © Los autores ISBN: 978-84-16678-22-8 Depósito Legal: VA 81-2018 Una publicación de: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de la Purísima Concepción "Casa de Cervantes", Calle del Rastro, nº 2. 47001 Valladolid ¥ 983 398 004 | www.realacademiaconcepcion.net Dirección del curso y coordinación editorial: Eloísa Wattenberg García CON EL PATROCINIO DE: —Edición impresa: AYUNTAMIENTO DE VALLADOLID Impresión: Imprenta Municipal —Edición digital: Primera edición: enero de 2018 Impreso en España. Printed in Spain ÍNDICE Pozos de nieve de Valladolid ............................................ 13 JESÚS ANTA ROCA | Escritor El área arqueológica del Mercado del Val (Valladolid) ...................... 25 EDUARDO CARMONA BALLESTERO | Arqueólogo Las Casas de Moneda de Valladolid ...................................... 51 JAVIER MOREDA | Arqueólogo La Real Cartuja de Nuestra Señora de Aniago. Revisiones y precisiones . 75 JESÚS URREA | Académico El Hospital General de Simón Ruiz de Medina del Campo. Una gran obra de mecenazgo ........................................... 109 ANTONIO PANIAGUA GARCÍA | Arquitecto El órgano barroco en Valladolid ......................................... 139 MIKEL DÍAZ-EMPARANZA | Universidad de Valladolid Reflejos del art déco en la arquitectura racionalista de Valladolid . 163 JOSÉ -

Alonso De Burgos Y La Fundación Y Primeros Estatutos Del Colegio De San Gregorio De Valladolid

Alonso de Burgos y la fundación y primeros estatutos del colegio de San Gregorio de Valladolid. La regulación de la vida religiosa y académica de los dominicos observantes en la Castilla del siglo XV Alonso de Burgos and the founding and first statutes of Saint Gregory college in Valladolid. The regulation of religious and academic life in the observantes Dominican friars in the Castilian 15th century Jorge DÍAZ IBÁÑEZ Profesor Titular de Historia Medieval Facultad de Geografía e Historia Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 3 de diciembre de 2015 Aceptado: 17 de febrero de 2016 RESUMEN En el presente trabajo se analiza primeramente el proceso de fundación, a fines del siglo XV, del colegio de San Gregorio de Valladolid por parte del obispo dominico, consejero y confesor real Alonso de Burgos; el colegio, de patronato real y centrado en los estudios de teología, estaba reser- vado exclusivamente para frailes predicadores observantes. A continuación, y como parte más am- plia y fundamental del estudio, se analizan los primeros estatutos que tuvo el colegio, otorgados por su fundador, ofreciéndose finalmente, en apéndice documental, su transcripción completa. PALABRAS CLAVE: Colegio de San Gregorio, Alonso de Burgos, Valladolid, siglo XV, dominicos, universidades, estatutos colegiales, teología. ABSTRACT In the present article we analyze in the first place the founding, at the end of 15 th century, of Saint Gregory college in Valladolid by the Dominican friar and bishop, royal confessor and counselor _____________ Este trabajo ha sido realizado en el marco del Proyecto de I+D del Programa Estatal de Fo- mento de la Investigación Científica y Técnica de Excelencia, Subprograma de Generación del Conocimiento, nº HAR2013-42211-P, de la Secretaría de Estado de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación, titulado Prácticas de Comunicación y negociación en las relaciones de consenso y pacto de la cultura política castellana, ca. -

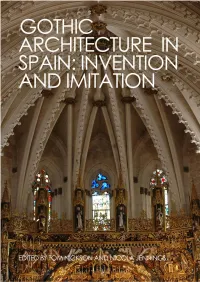

Gothic Architecture in Spain: Invention and Imitation

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN SPAIN: INVENTION AND IMITATION Edited by: Tom Nickson Nicola Jennings COURTAULD Acknowledgements BOOKS Publication of this e-book was generously Gothic Architecture in Spain: Invention and Imitation ONLINE supported by Sackler Research Forum of The Edited by Tom Nickson and Nicola Jennings Courtauld Institute of Art and by the Office of Scientific and Cultural Affairs of the Spanish With contributions by: Embassy in London. Further funds came from the Colnaghi Foundation, which also sponsored the Tom Nickson conference from which these papers derive. The Henrik Karge editors are especially grateful to Dr Steven Brindle Javier Martínez de Aguirre and to the second anonymous reader (from Spain) Encarna Montero for their careful reviews of all the essays in this Amadeo Serra Desfilis collection. We also thank Andrew Cummings, Nicola Jennings who carefully copyedited all the texts, as well as Diana Olivares Alixe Bovey, Maria Mileeva and Grace Williams, Costanza Beltrami who supported this e-book at different stages of its Nicolás Menéndez González production. Begoña Alonso Ruiz ISBN 978-1-907485-12-1 Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Managing Editor: Maria Mileeva Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Vernon Square, Penton Rise, King’s Cross, London, WC1X 9EW © 2020, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. -

An Islamicate History of the Alcazar of Seville: Mudejar Architecture and Andalusi Shared Culture (1252-1369 CE)

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Summer 8-7-2018 An Islamicate History of the Alcazar of Seville: Mudejar Architecture and Andalusi Shared Culture (1252-1369 CE) John Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Sullivan, John, "An Islamicate History of the Alcazar of Seville: Mudejar Architecture and Andalusi Shared Culture (1252-1369 CE)." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/67 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ISLAMICATE HISTORY OF THE ALCAZAR OF SEVILLE: MUDÉJAR ARCHITECTURE AND SHARED ANDALUSI CULTURE (1252-1369 CE) by JOHN F. SULLIVAN Under the Direction of Allen Fromherz, PhD ABSTRACT At the height of the Reconquista c. 1340 CE, Christian King Alfonso XI of Castile-León constructed a new throne room to commemorate his victory over Muslim forces from neighboring Granada and North Africa. The throne room called the Sala de la Justicia (Hall of Justice) was built almost entirely in the Mudéjar style, a style that looked Islamic in nature and included inscriptions in Arabic, several referencing the Qur’an, but predominantly intended for non-Muslims. The construction of this throne room in the Alcazar of Seville, a palace built by the Muslims and later used as the royal residence for the conquering Christians, has puzzled scholars due to its clearly Islamicate design being used in a new construction by a Christian ruler against a backdrop of the Crusades and the Reconquista in Spain. -

Valladolid, Ciudad Universitaria

VALLADOLID, CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA J. J. MARTÍN GONZÁLEZ La Universidad es una entidad cultural implantada en el medio urbano y que ejerce su función por medio del componente humano (profesores y alumnos) y de los edificios necesarios para la gestión. En Valladolid surgió la Universidad en el siglo XIV. Su historial es conocido por la Historia de Alcocer' y la publicada en 1989 por la propia institución'. Por los diversos estudios de esta última se conoce la organización y los diferentes cuerpos que la estructuran, es decir, la misma Universidad y los Colegios. En este estudio intentamos reflejar en el urbanismo de la ciudad la presencia de estos centros universitarios, abocando a la conclusión de que existió una zona pro- piamente representativa de tales estudios. Hay que partir del propio concepto de lo que sea un Estudio, primer nombre que se da al centro ocupado en la enseñanza superior. Hay que acudir a Las Partidas de Alfonso X el Sabio. El Estudio «es un ayuntamiento de maestros y discípulos» que se reúnen en un lugar común para el desempleo de la misión de «aprender las cien- cias»3. Se barajan tres posibilidades acerca del origen de la Universidad: traslado del Estudio de Palencia, creación de un Estudio en la Abadía, con carácter particular, y fundación del Concejo robustecida por el otorgamiento de privilegios por la Corona. Desde el punto de vista cronológico los hitos son los siguientes. En 1293 establece Sancho IV el Estudio de Alcalá de Henares, exigiendo que se atuviera al modelo del existente en Valladolid. En 1323 Alfonso XI hace ciertas concesiones «en razón del Estudio». -

The Spanish Habsburgs and the Arts of Islamic Iberia

THEHABSBURGSANDTHEIRCOURTSINEUROPE,1400–1700.BETWEENCOSMOPOLITISMANDREGIONALISM TheSpanishHabsburgsandtheArts ofIslamicIberia CatherineWilkinsonZernerȋȌ SpanishHabsburgswereacutelysensitivetoIslamicpresenceintheirterritories.BothCharlesVand PhilipII,forexample,bannedtheuseofArabicandNorthAfricanlanguagesaswellasIslamicdressin Catholic Spain. The Moriscos—a nominally Christian but formerly Islamic population living outside Granada—had been allowed to retain aspects of their Moorish identity, including language and dress.Theyrebelledin1568whentheseprivilegeswerewithdrawn.Whentherebellionhadbeen putdown,PhilipIIorderedtheMoriscosdispersedandresettledindifferentpartsofthecountryand hisson,PhilipIII,finallyorderedthemdeportedtoNorthAfricaandotherforeignlandsin1609–10. TheSpanishHabsburgreceptionofIslamicart—particularlyIslamicarchitecture—wasquitedifferent: they continued to use some Islamic buildings, which they chose to repair and extend rather than replace; and they integrated some features of Islamic origin into their classicizing Renaissance palaces. This makes one wonder what earlier Islamic art meant to these rulers. There is little scholarshiponthisissue,buttworesponsesbyearlymodernSpaniardstoIslamicartinSpainhave beenproposed:1)first,andmostgenerally,thatbythesixteenthcenturysomefeaturesofMoorish architecturehadbeensocompletelyassimilatedintotheartisticcultureofCatholicSpainthatthey werenolongerperceivedasIslamic;2)secondly,thatsomeIslamicbuildingsliketheGreatMosque atCórdobaandtheAlhambraPalaceinGranadaweretakenoverbytheChristiansandpreservedas -

Inventio in Valladolid's College of San Gregorio

136 Nicola Jennings 1377 Materialkonzepte zweier spanischer Grablegen im Spiegel von 84. Ceballos-Escalera y Gila, ‘Generación y semblanza’, Claus Sluters Werken für die Kartause von Champmol’, in B. p. 196. Borngässer Klein, H. Karge & B. Klein (eds.), Grabkunst und Sepulkralkultur in Spanien und Portugal. Arte funerario y cultura sepulcral en España y Portugal (Frankfurt am Main; Madrid: Vervuert, Iberoamericana, 2006), p. 95n13. 67. The Castilian convention of decorating tomb chests with narrative imagery, saints, weepers, and heraldry is demons- trated, for example, in María Jesús Gómez Bárcena, Escultura gótica funeraria en Burgos (Burgos: Diputacíon Provincial de Burgos, 1988). 68. See, e.g., K. Woods, ‘The Master of Rimini and the Tradition of Alabaster Carving in the Early Fifteenth-Century Netherlands’, in A. S. Lehmann, F. Scholten and P. Chapman (eds.), Meaning in Materials: Netherlandish Art, 1400-1800 (Leiden: Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, 2012), p. 62. 69. S. Nash, ‘«The Lord’s Crucifix of Costly Work- manship»: Colour, Collaboration and the Making of Meaning on the Well of Moses’, in V. Brinkmann, O. Primavesi, & M. Hollein (eds.), Circumlitio: The Polychromy of Antique and Me- dieval Sculpture (Munich: Hirmer, 2010), pp. 356-381. New Functions, 70. See, e.g., Molina de la Torre, Valladolid, pp. 40-41. The ongoing debate over the quatrain on the Ghent Altarpie- ce illustrates the difficulties inherent in evaluating medieval inscriptions. 71. Caja 7, Expt. 13, ASCT, and Caja 2, Expt. 22, New Typologies: ASCT. Villaseñor claims that construction must have been en- ded by 1431 on the basis the bull, but it seems more likely that of the bull was obtained in advance of the chapel’s completion.