Power of Memory and the Presence of a Collective History in Holocaust Literature| Analysis of Jewish and German Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch- sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Meeuwenoord, A.M.B. Publication date 2011 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meeuwenoord, A. M. B. (2011). Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Marieke Meeuwenoord 1 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad 2 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Jahresbericht !"#$

JAHRESBERICHT !"#$ 3 Inhalt 4 Vorstellung der Organisation 41 Engagement für Vielfalt und gegen Ausgrenzung 6 Rückblick 44 Internationale Bildungsarbeit 12 Ausblick 48 Ö"entlichkeitsarbeit 15 Freiwilligendienste 51 Ehrenamt 30 Highlights 54 Kirche und Gesellscha# 31 Symbol der Anerkennung: Die Freiwillige Annemarie Niemann begleitet Bundes- 57 Finanzen präsidenten beim Oradour-Besuch 34 Tschechien-Jubiläum: Lebendige 64 Danksagung Geschichte – Erinnern in der zweiten und dritten Generation 68 Organigramm 36 Familienbiogra!sche Überlegungen einer Belgien-Freiwilligen anlässlich 70 Impressum des Jubiläums 39 Sommerlager-Impression: Stumme Zeugen am Wegesrand 5 Man kann es einfach tun Die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Nationalsozialismus und seinen Verbrechen ist für Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste Motiv und Verpflichtung für konkretes Handeln in der Gegenwart. Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste steht in der mende an. In den Sommerlagern leben, lernen und Tradition der Bekennenden Kirche und trägt seit arbeiten internationale Gruppen für zwei bis drei 1958 im Rahmen von kurz- und langfristigen Frei- Wochen in unterschiedlichen Projekten. willigendiensten zu Frieden und Verständigung bei, setzt sich für Menschenrechte ein und sensibilisiert Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste sensibi- die Gesellscha# für die Auswirkungen der natio- lisiert für die heutigen Folgen des Nationalsozialis- nalsozialistischen Geschichte. Jährlich leisten rund mus und tritt aktuellen Formen von Antisemitismus, 180 Freiwillige in 13 Ländern ihren Friedensdienst. Rassismus und Ausgrenzung von Minderheiten ent- Sie begleiten ältere Menschen beispielsweise in jü- gegen. Gemeinsam mit deutschen und internatio- dischen Institutionen und Organisationen für Schoa- nalen Partner_innen engagiert sich Aktion Sühne- Überlebende, sie unterstützen sozial Benachteiligte zeichen Friedensdienste für die Entschädigung von sowie Menschen mit psychischen oder physischen Verfolgten des Nationalsozialmus und für die Rechte Beeinträchtigungen und sie engagieren sich in an- von Minderheiten. -

March May 5,1985

SPRING EVENTS ISSUE Volume LII, No. 6 April 15, 1985 Nisan 24, 5745 The observance of Yom HaShoa — Holocaust Remembrance Day has, in recent years, gained considerable recognition as an important date on the Jewish calendar. In communities throughout the world and especially in Israel and America congregations, schools and other organizations and institutions have marked this YOM HA'ATZMAUT SERVICE AND PROGRAM TO HONOR day with seriousness and commitment. We are ISRAEL INDEPENDANCE DAY proud that Kehilath Jeshurun has been in the forefront of this effort as more than 500 people THURSDAY EVENING - APRIL 25, at 7:30 P.M. now gather in our Main Synagogue each year. Once again, Kehilath Jeshurun will be the site anniversary and also honor the leaders and The Yom HaShoa program at KJ traditional¬ of a spirited observance and celebration of Yom citizens of the State who help all Jews stand tall ly begins with a memorial candle lighting Ha'atzmaut — Israel Independance Day. As is wherever we may be around the world. The ceremony in memory of the six million Jews traditional, we will begin our observance on songs reflect a pride in our people and the land who perished during the Holocaust. This year, Thursday evening, April 25 with the service in of Israel and leave us with the hope for peace we will once again ask members of our con¬ the Main Synagogue led by Cantor Avrum in the future. gregation who are survivors of the Holocaust Davis. The entire KJ community is invited to join as well as the adult children of survivors and Part two of the evening will be a ZIMRIAH with us on young children of survivors to light these OF SONGS FROM ISRAEL AND OUR THURSDAY EVENING, APRIL 25 memorial candles. -

6. DV-BEG.Pdf

Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Sechste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes (6. DV-BEG) 6. DV-BEG Ausfertigungsdatum: 23.02.1967 Vollzitat: "Sechste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes vom 23. Februar 1967 (BGBl. I S. 233), die zuletzt durch § 1 der Verordnung vom 24. November 1982 (BGBl. I S. 1571) geändert worden ist" Stand: Zuletzt geändert durch § 1 V v. 24.11.1982 I 1571 Fußnote (+++ Textnachweis Geltung ab: 18.9.1965 +++) Eingangsformel Auf Grund des § 42 Abs. 2 des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes in der Fassung des Gesetzes vom 29. Juni 1956 (Bundesgesetzbl. I S. 559, 562), zuletzt geändert durch das Gesetz vom 14. September 1965 (Bundesgesetzbl. I S. 1315), verordnet die Bundesregierung mit Zustimmung des Bundesrates: § 1 Als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG sind die in der Anlage aufgeführten Haftstätten anzusehen. § 2 (1) Soweit in der Anlage für einzelne Haftstätten bestimmte Zeiträume angegeben sind, gelten diese Haftstätten nur für die angegebenen Zeiträume als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG. (2) Die übrigen in der Anlage aufgeführten Haftstätten sind für den Zeitraum als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG anzusehen, während dem sie als geschlossene Lager in der Verwaltungsform eines Konzentrationslagers bestanden haben. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Zeiträume, in denen die Haftstätten dem Inspekteur der Konzentrationslager im SS-Hauptamt oder dem SS-Wirtschaftsverwaltungshauptamt, Amtsgruppe D, unterstanden haben. (3) Soweit in der Anlage für einzelne Haftstätten keine bestimmten Zeiträume angegeben sind, wird vermutet, daß diese Haftstätten am 1. November 1943 bestanden haben und von diesem Zeitpunkt an Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. -

Jean Améry and Wolfgang Hildesheimer: Ressentiments, Melancholia, and the West German Public Sphere in the 1960S and 1970S

JEAN AMÉRY AND WOLFGANG HILDESHEIMER: RESSENTIMENTS, MELANCHOLIA, AND THE WEST GERMAN PUBLIC SPHERE IN THE 1960S AND 1970S A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Melanie Steiner Sherwood January 2011 © 2011 Melanie Steiner Sherwood JEAN AMÉRY AND WOLFGANG HILDESHEIMER: RESSENTIMENTS, MELANCHOLIA, AND THE WEST GERMAN PUBLIC SPHERE IN THE 1960S AND 1970S Melanie Steiner Sherwood, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The dissertation revisits the West German literary scene of the 1960s and 1970s to investigate how two of its Jewish participants, Jean Améry and Wolfgang Hildesheimer, sought to promote ethical responses to the Holocaust. The study incorporates literary analysis and socio-political reflections on the ethics of public life. First, it is an analysis of the relationship between judicial confrontation of the German criminal past, the silence in the wider German cultural sphere in the wake of this confrontation, and the two writers’ efforts to expose and address this ethical disconnect (chapter I). Second, it draws attention to two very different modes of reactive affect, ressentiment and melancholia. Through readings of Hildesheimer’s novels Tynset (1965) and Masante (1973) in chapters II and III, on the one hand, and Améry’s essay “Ressentiments” (1966) and the essay-novel Lefeu oder Der Abbruch (1974) in chapters IV and V, on the other, the dissertation analyzes these two modes. Hildesheimer employed a register of ethical writing that articulated the interconnected processes of mourning and melancholia, but unlike recent scholarship that focuses on these categories and valorizes melancholia as source of productive socio-political action, Hildesheimer did not prescribe them as exemplary modes of affective reparation. -

Volunteer Translator Pack

TRANSLATION EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES 1. Principles for text, images and audio (a) General principles • Retain the intention, style and distinctive features of the source. • Retain source language names of people, places and organisations; add translations of the latter. • Maintain the characteristics of the source even if these seem difficult or unusual. • Where in doubt make footnotes indicating changes, decisions and queries. • Avoid modern or slang phrases that might be seem anachronistic, with preference for less time-bound figures of speech. • Try to identify and inform The Wiener Library about anything contentious that might be libellous or defamatory. • The Wiener Library is the final arbiter in any disputes of style, translation, usage or presentation. • If the item is a handwritten document, please provide a transcription of the source language as well as a translation into the target language. (a) Text • Use English according to the agreed house style: which is appropriate to its subject matter and as free as possible of redundant or superfluous words, misleading analogies or metaphor and repetitious vocabulary. • Wherever possible use preferred terminology from the Library’s Keyword thesaurus. The Subject and Geographical Keyword thesaurus can be found in this pack. The Institutional thesaurus and Personal Name thesaurus can be provided on request. • Restrict small changes or substitutions to those that help to render the source faithfully in the target language. • Attempt to translate idiomatic expressions so as to retain the colour and intention of the source culture. If this is impossible retain the expression and add translations in a footnote. • Wherever possible do not alter the text structure or sequence. -

A Tale of Two Brothers

A Tale of Two Brothers © Eli M. Noam 2007 992 Chapter 5.3 Uncle Max: Survivor 993 1 If Aunt Hedwig was the Saintly Sister and Aunt Kaete was the Pioneer Woman, Uncle Max was the Gutsy Survivor 994 He was the only prisoner ever to escape from the Nazi concentration camp Breendonk in Belgium. 995 2 Max Kaufmann 996 Lotte’s cousin Edith: “Periodically Uncle Max came and helped Grandfather with the bookkeeping. From time to time uncle Max drove far out into the countryside to businesses that needed a lot of materials. They were in small villages far away from Kassel. I often was permitted to go with him. They had an old car, and in those days the roads were full of rocks and had huge potholes after a rainstorm. We had to 997 Edithdrive Thorsen, Ud very fra Frankfurt, carefully. Manuskript til en ungdomsbiografi, Unpublished Memoirs, Copenhagen, 2007, translated by E. Noam, Rasmus Nielsen 3 Max (with dog), Hans (in crib), Hilde (sitting), Grandmother Adelheid, 998 and young mother Flora (on right) Lotte: “He had blue eyes and played football for one of the well known Kassel football clubs. Opposed to any kind of intellectual activity, he was the ‘goy’ of the family and quite logically he was engaged to a Christian woman. When they did not want to let go of each other [after the Nazis came to power], he was pursued for miscegenation (Rassens-chande), fled to Belgium, was caught there, and put in a concentration camp.” 999 Lotte Noam Memoir Letters to Birte 4 Max has no known descendents, and his story is reconstructed from a few old letters and newspaper clips. -

Documents Et Photographies De La Déportation Vers Les Camps

De l'arrestation aux camps Documents et photographies de la déportation vers les camps Lettre de René Bousquet, chef de la police de Vichy, la veille de la Rafle du Vél'd'hiv'. C'est la police française qui s'est chargée des arrestations. Les autobus utilisés à Paris lors de la rafle du Vél'd'hiv, les 16 et 17 juillet 1942. Les Juifs arrêtés furent conduits au Vélodrome d'Hiver puis à Drancy. C'est l'unique photo retrouvée dans les archives de presse. La censure interdit sa publication en juillet 1942. Vue générale du camp de Drancy en France où étaient amenées les Juifs arrêtés. Le camp est formé par des immeubles non terminés, sans fenêtres, en forme de U encadrant un vaste terain sur lequel est installé un baraquement. C'est de là que partaient les trains vers Auschwitz. (Reportage photographique réalisé par les nazis, Bibliothèque Nationale) Fillette juive endormie à Drancy, prête pour le départ. Les gendarmes français font monter les enfants dans les trains. Dessin de Cabu d'après des témoignages. Des Juives hongroises photographiées à travers la fenêtre d'un wagon au moment de leur déportation en 1944. Des fils de fer barbelé ont été placés devant la fenêtre. Arrivée d'un train de déportés hongrois le 26 mai 1944 sur la rampe d'Auschwitz- Birkenau. Au fond Autres lois antisémites Internement des Juifs étrangers Ordonnance du 4 octobre 1940 1. Les étrangers de race juive pourront être internés dans des camps spéciaux. 2. Les Juifs étrangers pourront en tous temps se voir assigner une résidence forcée. -

Key Findings Many European Union Governments Are Rehabilitating World War II Collaborators and War Criminals While Minimisin

This first-ever report rating individual European Union countries on how they face up their Holocaust pasts was published on January 25, 2019 to coincide with UN Holocaust Remembrance Day. Researchers from Yale and Grinnell Colleges travelled throughout Europe to conduct the research. Representatives from the European Union of Progressive Judaism (EUPJ) have endorsed their work. Key Findings ● Many European Union governments are rehabilitating World War II collaborators and war criminals while minimising their own guilt in the attempted extermination of Jews. ● Revisionism is worst in new Central European members - Poland, Hungary, Croatia and Lithuania. ● But not all Central Europeans are moving in the wrong direction: two exemplary countries living up to their tragic histories are the Czech Republic and Romania. The Romanian model of appointing an independent commission to study the Holocaust should be duplicated. ● West European countries are not free from infection - Italy, in particular, needs to improve. ● In the west, Austria has made a remarkable turn-around while France stands out for its progress in accepting responsibility for the Vichy collaborationist government. ● Instead of protesting revisionist excesses, Israel supports many of the nationalist and revisionist governments. By William Echikson As the world marks the United Nations Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, European governments are rehabilitating World War II collaborators and war criminals while minimising their own guilt in the attempted extermination of Jews. This Holocaust Remembrance Project finds that Hungary, Poland, Croatia, and the Baltics are the worst offenders. Driven by feelings of victimhood and fears of accepting refugees, and often run by nationalist autocratic governments, these countries have received red cards for revisionism. -

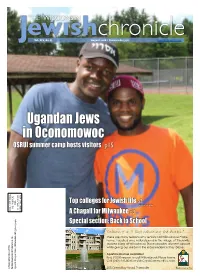

Ugandan Jews in Oconomowoc OSRUI Summer Camp Hosts Visitors P15

Vol. XCV, No. 8 August 2016 • Tammuz-Av 5776 JewishChronicle.org Ugandan Jews in Oconomowoc OSRUI summer camp hosts visitors p15 p3 PAID Top colleges for Jewish life SPECIAL SECTION U.S. POSTAGE MILWAUKEE WI MILWAUKEE PERMIT NO. 5632 NON-PROFIT ORG. A Chagall for Milwaukee p3 Special section: Back to School A free publication of the A free Inc. Milwaukee Jewish Federation, WI 53202-3094 Milwaukee, Ave., N. Prospect 1360 2 • Section I • August 2016 Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle JewishChronicle.org August 2016 • Section I • 3 A GUIDE TO ewish CANDLELIGHTING TIMES J Wisconsin 5777-5778 / 2016-2017 Milwaukee Madison Green Bay Wausau Q uotable A rt A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin August 5 7:49 p.m. 7:55 p.m. 7:53 p.m. 8:01 p.m. * * * * * * Get your FREE copy today! Contact Tela Bissett August 12 7:40 p.m. 7:46 p.m. 7:43 p.m. 7:51 p.m. Local Chagall tied to Israel, “I am standing here and turning to you, “I think the Jewish community should look at (414) 390-5720 • [email protected] Your connection to Jewish Arts, Culture, Education, Camping and Religious Life August 19 7:29 p.m. 7:35p.m. 7:32 p.m. 7:40 p.m. Arab mother. I raised my daughter to love, the big picture. The Democrats, the last eight and you raised your son to hate and sent him years, have not been friends of Israel. Republi- Golda Meir and dreams August 26 7:18 p.m. 7:24 p.m. 7:20 p.m. -

Legislating Atrocity Prevention

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLL\57-1\HLL105.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-JAN-20 14:36 ARTICLE LEGISLATING ATROCITY PREVENTION ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN* Despite promises made by the international community after the Holocaust to “never again” allow genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity to be committed, these “atrocity crimes” have been perpetrated again and again. To- * Associate Professor of Law and Political Science, University of Houston Law Center, with additional appointments in the University of Houston’s Department of Political Science and Hobby School of Public Affairs. J.D., Yale Law School; D.Phil. (Ph.D.) and M.Phil., both in International Relations, Oxford University (Marshall Scholar); B.A. in Political Science, Yale University. Research for this Article was generously facilitated by institutional support from Stanford Law School (where the author was a Lecturer from 2017 to 2019) and Harvard University Kennedy School of Government (where the author was a Senior Fellow from 2016 to 2019). While serving on the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee (“SFRC”) staff in 2016-17 as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow, the author drew on his book, United States Law and Policy on Transitional Justice: Principles, Politics, and Pragmatics (Oxford University Press, 2016), to work as a lead architect of both the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act and the Syrian War Crimes Accountability Act. The author has subsequently advised the White House National Security Council (“NSC”) and SFRC on im- plementing both laws. On June 13, 2019, an earlier draft of this Article was submitted for the record by Stanford Law School Professor Beth Van Schaack at a congressional hearing, “Pursuing Accountability for Atrocities,” hosted by the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission. -

Master Document Template

Copyright by Robert George Kohn 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Robert George Kohn Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Language of Uncertainty in W.G. Sebald’s Novels Committee: Pascale Bos, Supervisor Sabine Hake John Hoberman Philip Broadbent David Crew The Language of Uncertainty in W.G. Sebald’s Novels by Robert George Kohn, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation would not have been possible without the amazing and generous support, both emotional and intellectual, as well as incredible patience of my lovely and kind wife, Nadine Cooper-Kohn. I would like to, therefore, dedicate this study to her as a small token of my gratitude for being at my side through it all. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the following people for their help and contributions they have made to my intellectual and personal growth during my graduate career. First and foremost, I would like to recognize my wife, Nadine Cooper-Kohn for her steadfast support, inspiration and love throughout these past seven years. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Pascle Bos, for her patience and understanding throughout the process of writing, as well as for encouraging me during difficult times. The helpful feedback of Dr. Sabine Hake and Dr. John Hoberman inspired me and helped me to see this project through.