UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amiri Baraka Biography Pdf

Amiri baraka biography pdf Continue Amiri Baraka is a well-known African-American writer in fiction, drama, poetry and music. With books such as Tales of the Out and the Gone, he has received the PEN Open Book Award and is also honored as one of the most widely published African-American writers of his generation. In addition to writing, Baraka is considered a revolutionary political activist and has lectured extensively on various political and cultural issues throughout Europe, Africa, the United States and the Caribbean. Born in 1934, Amiri Baraka grew up in the United States. While studying philosophy and religion at Columbia University, he has a solid knowledge of these subjects, which are also well reflected in his writings. Baraka began his professional career by joining the U.S. Air Force in the early '50s. He was destined to be a skilled writer, he did not serve the army for long and switched to a completely different domain by choosing to work in storage for music records. Here, his social circle expanded and added Black Mountain Poets, New York School Poets and Beat Generation. In addition, it developed his interest in Jazz music, which later matured to make him one of the most sought-after music critics. Amiri Baraka is inspired by a number of musical orishai, including John Coltrane, Malcolm X, Ornette Coleman and Thelonius Monk, who led him to become founder of the Black Art Movement of the 60s. His research on African-American music and the play Dutchman and Blues People is commendable. His published collection of essays The essence and poems of substitution, such as Somebody Blowup America, also added to his name. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Superintendent Territorial Prison YUMA, Arizona, June 30Th, 1902

Oemplimente of W. lI. GRIFFITH, Superintendent. .' J 'I MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF CONTROL OFFICE IN THE CAPITOL BUILDING Phoen~-Arizo~a. ALEXANDER O. BRODIE, Governor W. F. NICHOLS, Auditor E. J. BENNITT, Citizen Member and Secretary FRANKLIN D. LANE, Clerk OFFICERS OF THE TERRITORIAL PRISON At Yuma, Arizona. Wm. M. GRIFFITH, Superintendent U. G. WILDER, Assistant Superintendent WALTER T. GREGORY, Secretary OFFICERS OF THE INSANE ASYLUM OF ARIZONA Phoenix, Arizona. DR. W. H. WARD, Superintendent ALLY K WARD, Matron J. H. KIRKLAND, Acting Steward BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE Board of Control of Arizona. OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF CONTROL, PHOENIX, Arizona, July 1st, 1902. Hon. Alexander O. Brodie, Governor of Arizona.. Sir: In accordance with Paragraph No. 287, Revised Statutes of Arizona, of 1901, I have the honor to present the fourth binennial report of the Board of Control of Arizona, together with the reports of the super· intendents of the Territorial Prison at Yuma, Arizona, and the Insane Asylum of Arizona, at Phoenix. In presenting this report for your consideration, we do not claim that it is a marvel either of the cheapness or expense in the maintenance of either of the institutions reported herein, but we do expect to show that they have been conducted as cheaply as was prudent, having in mind the welfare of the Territory as well as that of the inmates. The prices of all kinds of food products and clothing have been higher and subject to more violent fluctuation than for any biennial period since the establishment of this Board, and if indeed the cost of maintenance has not exceeded that of previous years, it is solely due to the watchful care and efficiency of the superintendents in charge. -

New Class Is Cat's Meow for Aspiring Veterinary Assistants

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY Boy Scouts converge at Deseret Peak See B1 TOOELETRANSCRIPT CHOSEN Best Small by the SOCIETY OF Newspaper PROFESSIONAL 2009 in Utah JOURNALISTS BULLETIN 2010& SeptemberSeptember 21,21, 2010 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 117 NO. 33 50¢ Report casts new light on school safety District officials say incident increases are down to better reporting, not more problems by Tim Gillie STAFF WRITER Despite a report that shows a rapid upswing in the number of students involved in unsafe behaviors, Tooele County School District offi- cials claim that local schools are a safe place for students. The district released its annual safe schools report at a school board meeting Sept. 7. The report shows almost every category of incident increased dramatically over the past year. For example, 143 students were report- ed to be involved in simple assault incidents in 2010 compared to 12 in 2009, and 490 cases of truancy were reported in 2010 compared to 76 in 2009. The large increases in reported incidents are due to a better method of data collec- tion, not necessarily an actual increase in the number of incidents, according to Dan Johnson, Tooele County School District sec- Maegan Burr ondary education director. Tooele City Police Officer Heath Hillyard watches the lunch line from the second floor of Tooele High School Wednesday afternoon. Despite an increase in the number of reported violent and SEE SAFETY PAGE A6 ➤ drug-related incidents, district officials maintain schools are generally safe. New class is cat’s meow for aspiring veterinary assistants by Tim Gillie STAFF WRITER Tooele High School junior Austin Remick brought his pigs to school one day last week. -

UCSC:ISIM Conference:Festival 2009 Program

Monday, November 23, 2009 Welcome to the 2009 UCSC/ISIM Festival/Conference at the University On behalf of the ISIM Board of of California Santa Cruz! The title of Directors and Advisory Council, I am this year's event is "Improvisation, happy to welcome you to the University Diversity and Change: Uncovering of California at Santa Cruz campus for New Social Paradigms within ISIM’s fourth annual conference, held in Spontaneous Musical Creativity." We collaboration with the USCS are grateful to the Porter College Improvisation Festival. We are honored Festival Fund at UCSC for its to join forces with Festival Drector generous support. We are also fortunate for the collaborative Karlton Hester, who is also ISIM Vice President and Board Member, sponsorship with the International Society for Improvised Music. and his wonderful staff in what will undoubtedly be a memorable There are over sixty assorted events scheduled for your enjoyment occasion for all involved. It is difficult to imagine a more timely and edification, jam packed with concerts, films, workshops, panel theme in today’s world than diversity, nor a more powerful vehicle for discussions, and other presentations with guests from around the broaching this topic than musical improvisation. As you can see from world. We hope that you will find ways to become directly involved in the enclosed schedule, the next few days will feature an extraordinary some of these activities that allow you to also improvise. This is a line up of performances and presentations that exemplify this vision. continuation of our ongoing campus effort aimed at "Rebuilding In addition to the formally scheduled events, one of my favorite Global Community through the Arts." We hope that you continue to aspects of our gatherings are the many informal conversations and support improvised music, the arts, and the creative process. -

Grocery Stores

Grocery Stores: Neighborhood Retail or Urban Panacea? Exploring the Intersections of Federal Policy, Community Health, and Revitalization in Bayview Hunters Point and West Oakland, California By Renee Roy Elias A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jason Corburn, Chair Professor Karen Chapple Professor Malo Hutson Professor Margaret Weir Fall 2013 Abstract Grocery Stores: Neighborhood Retail or Urban Panacea? Exploring the Intersections of Federal Policy, Community Health, and Revitalization in Bayview Hunters Point and West Oakland, California By Renee Roy Elias Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Jason Corburn, Chair Throughout the nation, grocery retailers are reentering underserved communities amidst growing public awareness of food deserts and the rise of federal, state, and local programs incentivizing urban grocery stores. And yet, even with expanding research on food deserts and their public health impacts, there is still a lack of consensus on whether grocery stores truly offer the best solution. Furthermore, scholars and policymakers alike have limited understandings of the broader neighborhood implications of grocery stores newly introduced into underserved urban communities. This dissertation analyzes how local organizations and agencies pursue grocery development in order to understand the conditions for success implementation. To do this, I examine the historical drivers, planning processes, and outcomes of two extreme cases of urban grocery development: a Fresh and Easy Neighborhood Market (a chain value store) in San Francisco’s Bayview Hunters Point and the Mandela Foods Cooperative (a worker-owned cooperative) in Oakland’s West Oakland districts. -

Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21St Century

Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century By Samuel Bañales A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Fall 2012 Copyright © by Samuel Bañales 2012 ABSTRACT Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century by Samuel Bañales Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California at Berkeley Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair By focusing on the politics of age and (de)colonization, this dissertation underscores how the oppression of young people of color is systemic and central to society. Drawing upon decolonial thought, including U.S. Third World women of color, modernity/coloniality, decolonial feminisms, and decolonizing anthropology scholarship, this dissertation is grounded in the activism of youth of color in California at the turn of the 21st century across race, class, gender, sexuality, and age politics. I base my research on two interrelated, sequential youth movements that I argue were decolonizing: the various walkouts organized by Chican@ youth during the 1990s and the subsequent multi-ethnic "No on 21" movement (also known as the "youth movement") in 2000. Through an interdisciplinary activist ethnography, which includes speaking to and conducting interviews with many participants and organizers of these movements, participating in local youth activism in various capacities, and evaluating hundreds of articles—from mainstream media to "alternative" sources, like activist blogs, leftist presses, and high school newspapers—I contend that the youth of color activism that is examined here worked towards ontological, epistemological, and institutional decolonization. -

Nature of Homicide: Trends and Changes

The Nature of Homicide: Trends and Changes Proceedings of the 1996 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group Santa Monica, California Editors Pamela K. Lattimore CynthiaA. Nahabedian Foreword These are the proceedings of the 1996 annual meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. The meeting was hosted by the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California from June 9 to June 12, 1996. The Proceedings include nine sections that correspond closely with the areas of presentation and discussion outlined in the program agenda. Recorder's notes and discussion summaries, when made available, were included. A copy of the meeting agenda, and a list of program participants and active members are included in the appendices. Thanks to all for your participation. Pamela K. Lattimore Cynthia A. Nahabedian Editors CONTENTS FOREWORD................................................................................................................i SECTION ONE: THE HOMICIDE RESEARCH WORKING GROUP.......................................2 THE HOMICIDE RESEARCH WORKING GROUP: PAST AND PRESENT ROLAND CHILTON................................................................ .4 THE HOMICIDE RESEARCH WORKING GROUP'S FIRST FIVE YEARS: WHAT HAS BEEN DONE? WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE? ROLAND CHILTON...............................................................12 SECTION TWO: INTEGRATING THEORIES OF LETHAL VIOLENCE............................... .22 THEORIZING ABOUT HOMICIDE: A PRESENTATION ON THE THEORIES EXPLAINING HOMICIDE AND OTHER CRTRJES CHRISTINE E. RASCHE...................................................... -

Obituary Collection

Clipping Files: Obituary Collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Note: Date(s) are usually the earliest date obituary appeared in newspaper, or where possible a date of death. True date of death appears in service programs if in file or if mentioned in Biography files. A Abdulah, Obadiah Yusuf 05/28/2003 Abernethy, Kathryn Marie 05/04/1999 Abiakam, “Chi” Ifeoma 10/19/2009 Abraham, George Earvin, SR. 01/08/2010 Abraham, Solomon 09/12/2008 Abram Gerelane “Geri” 04/14/2012 Abram, Regina Annette 05/10/2012 Caldwell-Kirk Mortuary Abrams, Harold Nelson 05/02/2012 Ballard Family Mortuary Abron, Lois 05/04/1943 Adair, Phyllis Uvonne 04/18/2008 Adams, Arianna T. “Baby” 07/21/2009 Adams, Barcus Birdine Rev. 11/20/2009 Adams, Carol Y. 02/28/2008 Adams, Corean 05/12/2008 Adams, Corean 05/11/2008 Adams, Curtis 03/05/2008 Adams, David Malakhi 08/03/2010 Adams, Evelin 05/12/2009 Adams, Gloria Jean 09/11/2009 Adams, Iola 09/10/2008 Adams, J. H. 10/12/2010 Adams, Mozell 04/12/2009 Adams, Preston B. Sr. 01/11/2013 Caldwell-Kirk Mortuary 1 Adams, Robert C. Sr. 10/21/2010 Adams, Rosie Mae 12/28/2010 Adams, Shoshone A. 09/11/2009 Adams, The Rev. Sidney Ph.D. 06/11/2003 Adams, Theodore R. 06/15/2003 Adams, Theodore R., Sr. 02/10/1995 Adams, Thomas Albert 04/30/2010 Adams, Virgil Oliver 01/28/2012 Adams, Vonda “V MaMa” 08/31/2009 Adams, Zula Ray 05/01/1987 Addison, Cathy E. -

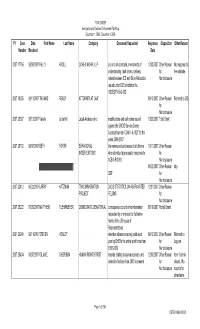

FY Case Number Date Received First Name Last Name Company

FOIA 09-0593 Immigration and Customs Enforcement FOIA Log December 1, 2006 - December 1, 2008 FY Case Date First Name Last Name Company Document Requested Response Disposition Other Reason Number Received Date 2007 17796 09/06/2007 KELLY KROLL COHEN MOHR, LLP any and all contracts, memoranda of 12/03/2007 Other Reason No response to understanding, task orders, delivery for fee estimate orders between ICE and Sirva Relocation Nondisclosure issued under ICE solicitation No. HSCEOP-05-Q-002 2007 18255 09/11/2007 THOMAS READY ATTORNEY AT LAW 09/12/2007 Other Reason Referred to CIS for Nondisclosure 2007 20397 09/13/2007 Valerie Underhill Labat-Anderson Inc. modifications and call orders issued 10/23/2007 Total Grant against the USCIS Service Center Contract Number COW-1-A-1027 for the years 2006-2007 2007 20702 09/07/2007 BETH FORTH BEHAVIORAL the names and addresses of all offerors 10/11/2007 Other Reason INTERVENTIONS who submitted a proposal in response to for ACB-3-R-0033 Nondisclosure (b)(6) 08/22/2007 Other Reason cbp CBP for Nondisclosure 2007 22412 06/22/2007 LARRY KATZMAN TRAC IMMIGRATION DACS STATISTICS ON AGGRAVATED 12/31/2007 Other Reason PROJECT FELONS for Nondisclosure 2007 25222 07/26/2007 MATTHEW FUEHRMEYER DEMOCRATIC SENATORIAL correspondence and other information 08/10/2007 Partial Grant requested by or provided to Katherine Harris of the US house of Representatives 2007 25240 09/11/2007 STEVEN HEALEY retention allowance money paid each 09/12/2007 Other Reason Referred to year by DHS for its entire work force from for Laguna 1998-2003 Nondisclosure 2007 25434 09/07/2007 GILIANE CHERUBIN HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST records relating to asylum seekers and 12/03/2007 Other Reason Item 1 admin detention facilities from 2000 to present for closed. -

African American Family Histories and Related Works in the Library Of

African American Family Histories and Related Works in the Library of Congress Compiled by Paul Connor, updated by Ahmed Johnson Local History and Genealogy Reading Room Humanities and Social Sciences Division Library of Congress Washington 2009 Introduction Revised in 2009, this edition of African American Family Histories and Related Works in the Library of Congress incorporates all the past efforts of Sandra Lawson and Paul Connor, supplemented by the edition of 84 family histories and genealogical handbooks. Because of the changing technological environment since the first publication of this guide, links to the Library of Congress vast collection of digitized records and resources related to the African American experience in America have been included covering African American culture and society, places, slave narratives, military records, and resource guides. These electronic resources include digitized oral histories, newspapers, maps, and photographs. The addition of these digital resources and books published after 1997 enriches the avai lability of resources pertaining to African American family histories at the Library of Congress. In the previous edition, Paul Connor selected 183 books that were cataloged during the period 1973-1997, covering topics ranging from abolitionists, American Loyalists, and revolutionaries to masters and slaves, freedmen, Civil War soldiers, and Cherokee Indians. In addition to published genealogies, the researcher will find references to handbooks on planning family reunions, abstracts of newspaper notices, and even some abstracts of funeral programs. The individual states under which these books have been cataloged are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. Illustrations are included in 130 of the publications, and many of them also cite bibliographical references. -

UCSC:ISIM Conference:Festival 2009 Program

Welcome to the 2009 UCSC/ISIM Festival/Conference at the University of California Santa Cruz! The title of this year's event is "Improvisation, Diversity and Change: Uncovering New Social Paradigms within Spontaneous Musical Creativity." We are grateful to the Porter College Festival Fund at UCSC for its generous support. We are also fortunate for the collaborative sponsorship with the International Society for Improvised Music. There are over sixty assorted events scheduled for your enjoyment and edification, jam packed with concerts, films, workshops, panel discussions, and other presentations with guests from around the world. We hope that you will find ways to become directly involved in some of these activities that allow you to also improvise. This is a continuation of our ongoing campus effort aimed at "Rebuilding Global Community through the Arts." We hope that you continue to support improvised music, the arts, and the creative process. Student and community involvement is important to the success of this project. In addition to campus presentations, we will also have community concerts and projects that we hope you will attend. We thank you for your support and hope that you enjoy our events! Best wishes, Karlton Hester, UCSC Festival Director Krystal Zamora, UCSC Festival Administrative Assistant 1 On behalf of the ISIM Board of Directors and Advisory Council, I am happy to welcome you to the University of California at Santa Cruz campus for ISIM’s fourth annual conference, held in collaboration with the USCS Improvisation Festival. We are honored to join forces with Festival Drector Karlton Hester, who is also ISIM Vice President and Board Member, and his wonderful staff in what will undoubtedly be a memorable occasion for all involved.