Vi. the Dialect of West Somerset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonics Spelling Words Grade K 1 2.CA

Benchmark Advance Grade 1 Phonics Skills and Spelling Words Unit Week Phonics Spiral Review Spelling Words had, has, pack, ran, see, she, back, cap, sack, 1 Short a N/A pans Short i; 1 2 Short a big, him, hit, kick, kids, lid, little, you, fit, lips Plural Nouns Short o; box, doll, hot, jump, lock, mop, one, rock, 3 Short i Double Final Consonants tops, cots ten, jet, fed, neck, let, mess, look, are, beg, 1 Short e Short o sell Short u; come, cup, duck, dull, here, nut, rug, cub, sun, 2 2 Short e Inflectional Ending -s cuff class, clock, flat, glad, plan, put, what, slip, 3 l-Blends Short u black, plums r-Blends: br, cr, dr, fr, gr, pr, tr; brim, crab, trim, went, frog, drip, grass, prop, 1 l-Blends Singular Possessives trip, now s-Blends: sk, sl, sm, sn, sp, st, sw; skip, step, skin, smell, out, was, spin, sled, 3 2 r-Blends Contractions with ’s spot, slip Final Consonant Blends: nd, nk, nt, mp, st; jump, and, pink, hand, nest, went, who, good, 3 s-Blends Inflectional Ending -ed trunk, best Consonant Digraphs th, sh, ng; bath, bring, our, shop, shut, these, thing, 1 Final Consonant Blends nd, nk, nt, mp, st Inflectional Ending -ing wish, this, rang Consonant Digraphs ch, tch, wh; Consonant Digraphs chop, lunch, catch, check, once, when, whiff, 4 2 Closed Syllables th, sh, ng much, match, hurt Three-Letter Blends scr, spl, spr, squ, str; split, strap, scrub, squid, stretch, scratch, 3 Consonant Digraphs ch, tch, wh Plurals (-es) because, when, sprint, squish take, made, came, plate, brave, game, right, 1 Long a (final -e) Three-Letter -

Unit #1 Short a and I Unit #2 Short O and E Land Crop Plan Clock Stand

Unit #1 Short a and i Unit #2 Short o and e land crop plan clock stand drop act plot last block band flock grand test stamp spent sand left stick sled trip spend thing west lift tent swim desk list nest Unit #3 Short u sound Spelling Unit #4 /oi/ and /ou/ lunch boil until join buzz voice stuff oil dull point study soil uncle proud cuff loud under house cover cloud become sound nothing round month south love found none ground Unit #5 ew and oo Unit #7 Vowel-Consonant-e crew state news face drew pave knew flame threw skate chew plane loose slide school size smooth prize pool smile shoot close roof globe fool smoke balloon broke choose stone Unit #8 Long a: ai, ay Unit #9 Long e: ee, ea aid sheep chain street mail wheels paint cheese plain sweet main dream pail east laid treat paid mean pay peace tray real maybe leave lay stream always teacher away heat Unit #10 Long i: i, igh Unit #11 Long o: ow, oa, o night snow bright load find almost light row wild soak high window blind foam fight most sight flow kind goat sign throw knight float mild blow right below sigh soap Unit #13 sh,ch,tch,wr,ck Unit #14 Consonants /j/,/s/ shape change church age watch large father page wrap fence check space finish center sharp since mother price write ice catch dance chase pencil shall slice thick place wrote city Unit #15 Digraphs, Clusters Unit #16 Schwa Sound shook afraid flash around fresh upon splash never speech open stitch animal scratch ever switch about stretch again strong another string couple spring awake think over cloth asleep brook above Unit -

Zap-Ext-Light18.Psftx Linux Console Font Codechart

zap-ext-light18.psftx Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x013 U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Filename: zap-ext-light18.psftx PSF version: 1 0x014 U+203A SINGLE RIGHT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Glyph size: 8 × 18 pixels Glyph count: 512 0x015 U+201C LEFT DOUBLE QUOTATION Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) MARK, U+201F DOUBLE HIGH-REVERSED-9 QUOTATION MARK Unicode mappings 0x016 U+201D RIGHT DOUBLE 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT QUOTATION MARK, CHARACTER U+02EE MODIFIER LETTER DOUBLE 0x001 U+03C0 GREEK SMALL LETTER PI APOSTROPHE 0x002 U+2260 NOT EQUAL TO 0x017 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x003 U+2264 LESS-THAN OR EQUAL TO 0x018 U+2E42 DOUBLE LOW-REVERSED-9 0x004 U+2265 GREATER-THAN OR EQUAL QUOTATION MARK TO 0x019 U+2E41 REVERSED COMMA, 0x005 U+25A0 BLACK SQUARE, U+02CE MODIFIER LETTER LOW U+25AC BLACK RECTANGLE, GRAVE ACCENT U+25AE BLACK VERTICAL 0x01A U+011E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G RECTANGLE, WITH BREVE U+25FC BLACK MEDIUM SQUARE, U+25FE BLACK MEDIUM SMALL 0x01B U+011F LATIN SMALL LETTER G SQUARE, WITH BREVE U+2B1B BLACK LARGE SQUARE, 0x01C U+0130 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I U+220E END OF PROOF WITH DOT ABOVE 0x006 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01D U+0131 LATIN SMALL LETTER U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT, -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

TLD: Сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012

TLD: сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012 Registry: сайт Registry Contact: Iliya Bazlyankov <[email protected]> Tel: +359 8 9999 1690 Website: http://www.corenic.org This document presents a character table used by сайт Registry for IDN registrations in Cyrillic script. The policy disallows IDN variants, but prevents registration of names with potentially similar characters to avoid any user confusion. U+002D;U+002D # HYPHEN-MINUS -;- U+0030;U+0030 # DIGIT ZERO 0;0 U+0031;U+0031 # DIGIT ONE 1;1 U+0032;U+0032 # DIGIT TWO 2;2 U+0033;U+0033 # DIGIT THREE 3;3 U+0034;U+0034 # DIGIT FOUR 4;4 U+0035;U+0035 # DIGIT FIVE 5;5 U+0036;U+0036 # DIGIT SIX 6;6 U+0037;U+0037 # DIGIT SEVEN 7;7 U+0038;U+0038 # DIGIT EIGHT 8;8 U+0039;U+0039 # DIGIT NINE 9;9 U+0430;U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A а;а U+0431;U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE б;б U+0432;U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE в;в U+0433;U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GHE г;г U+0434;U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE д;д U+0435;U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE е;е U+0436;U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE ж;ж U+0437;U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE з;з U+0438;U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER I и;и U+0439;U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT I й;й U+043A;U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA к;к U+043B;U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL л;л U+043C;U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM м;м U+043D;U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN н;н U+043E;U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O о;о U+043F;U+043F -

Regional Phonological Variants in Louisiana Speech

REGIONAL PHONOLOGICAL VARIANTS IN LOUISIANA SPEECH By August Weston Rubrecht A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1971 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. F. G. Cassidy, Jr., director of the Dictionary of American Regional English, for permission to use the tape recordings on which this study is based, and I want to thank him and the Dictionary staff for doing what they could from such a distance to make the field work as pleasant as possible. I especially recall Mrs. Laura Ducker's cheering notes and letters, and Dr. James Hartman's consideration in assigning additional communities once those in Louisiana had been finished. The names of all those in Louisiana who helped make the field work easier and the field worker more comfortable would comprise a list too long to give here. It would include all my informants, not just those who made tapes, and all those who helped direct me to prospec- tive informants, together with many others whose hospitality I enjoyed. I am especially grateful to the William R. Van Ripers at LSU in Baton Rouge and to Miller Williams, Thomas Preston, and John Mosier and their families at Loyola in New Orleans for their hospitality and assistance. In the writing of the dissertation, I gratefully acknowledge the advice and suggestions of my chairman. Dr. John Algeo, who has helped me avoid or correct a great many errors, omissions, and infelicitous turns of phrase. -

Interim Report: the Refinement of the Test Battery to Assess Word Identification Skills. Report from the Project on Studies in Language: Reading and Communication

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 194 575 TM BOO 704 AUTHOR Johnson, Dale D.; And Others TITLE Interim Report: The Refinement of the Test Battery to Assess Word Identification Skills. Report from the Project on Studies in Language: Reading and Communication. INSTITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison. Research and Development center for Individualized Schooling. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEWI, WaShington, D.C. REPORT NO WRDCIS-Ti -544 PUB DATE Jul 80 GRANT OB-NIE-G-B0-0117 NOTE BBp. EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Consonants: *Diagnostic Tests: Elementary Education; *Item Analysis; *Phonics; *Structural Analysis (Linguistics): Test Construction; Vowels; *Word Recognition IDENTIFIERS *Word Identification Test (Johnson et al) ABSTRACT The research discussed in this- report is a continuation of an effort -to develop _a set of- diagnostic subtests in phonics and structure with empirically determined mastery levels. The complete test_ will assess the word identification skillt of elementary school children. Revisions made in_the_test_battery f011eiVii*ag_administration±of_ the Phorics_and_Structure Subtests are_ documented. A study in which the revised_subtests were- administered to -BO grade 2 and 3 pupils is also_ described. Item analysis information:for use in_the preparation of the subtests ror the final administration of the Word Identification -Test battery is presented. These_revisions_will improve the diagnostic precision Cf the tests and eliminate concerns regarding correct response position and frequency of occurrence of specific distracter categories. Results of evaluating the grade level appropriateness of each subtest_indicated; (1) the Phonics Subtests could be administered-to younger children tgrade_1); and (2) the Structure Subtests could be administered to older children (grades -4 and 5 for affixes, and grade 4 or possessives ard contractions). -

Multilingualism, the Needs of the Institutions of the European Community

COMMISSION Bruxelles le, 30 juillet 1992 DES COMMUNAUTÉS VERSION 4 EUROPÉENNES SERVICE DE TRADUCTION Informatique SdT-02 (92) D/466 M U L T I L I N G U A L I S M The needs of the Institutions of the European Community Adresse provisoire: rue de la Loi 200 - B-1049 Bruxelles, BELGIQUE Téléphone: ligne directe 295.00.94; standard 299.11.11; Telex: COMEU B21877 - Adresse télégraphique COMEUR Bruxelles - Télécopieur 295.89.33 Author: P. Alevantis, Revisor: Dorothy Senez, Document: D:\ALE\DOC\MUL9206.wp, Produced with WORDPERFECT for WINDOWS v. 5.1 Multilingualism V.4 - page 2 this page is left blanc Multilingualism V.4 - page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. INTRODUCTION 1. LANGUAGES 2. CHARACTER RÉPERTOIRE 3. ORDERING 4. CODING 5. KEYBOARDS ANNEXES 0. DEFINITIONS 1. LANGUAGES 2. CHARACTER RÉPERTOIRE 3. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONCERNING ORDERING 4. LIST OF KEYBOARDS REFERENCES Multilingualism V.4 - page 4 this page is left blanc Multilingualism V.4 - page 5 0. INTRODUCTION The Institutions of the European Community produce documents in all 9 official languages of the Community (French, English, German, Italian, Dutch, Danish, Greek, Spanish and Portuguese). The need to handle all these languages at the same time is a political obligation which stems from the Treaties and cannot be questionned. The creation of the European Economic Space which links the European Economic Community with the countries of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) together with the continuing improvement in collaboration with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe oblige the European Institutions to plan for the regular production of documents in European languages other than the 9 official ones on a medium-term basis (i.e. -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK -

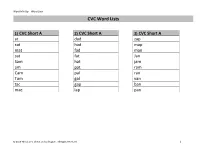

CVC Word Lists

Word Mix Up – Word Lists CVC Word Lists 1) CVC Short A 2) CVC Short A 3) CVC Short A at dad zap cat had map mat fad man sat fat Jan Sam hat jam am pat ram Cam pal ran Tam gal van tac gap ban mac lap pan © 2016 Theodore J. Christ and Colleagues. All Rights Reserved. 1 Word Mix Up – Word Lists 4) CVC Short O 5) CVC Short O 6) CVC Short O got wow Tom lot how top log now pop dog bow pod cog boss Tod cod toss toss cot loss Ross tot lot rod Tom hot rot mom hop not Note. If correct spelling is also an objective of the lesson, teach or remind that two of the same letters go together and make the same sound at end of word (examples: s, t, l, z) © 2016 Theodore J. Christ and Colleagues. All Rights Reserved. 2 Word Mix Up – Word Lists 7) CVC Short I 8) CVC Short I 9) CVC Short I sit bit zip lit hit tip fit pit lip mitt pig lick miss big pick mid wig pin lid win Zin did bin Zig dim bib fig Tim rib dig Note. If correct spelling is also an objective of the lesson, teach or remind how “c” and “k” work together to make the same sound as /c/ or /k/. © 2016 Theodore J. Christ and Colleagues. All Rights Reserved. 3 Word Mix Up – Word Lists 10) CVC Short U 11) CVC Short U 12) CVC Short U mud tug hut mug bug cut lug dug but dug duck bud hug luck buzz hum tuck bug sum tub pug gum cub pup Gus cut cup gull nut cud © 2016 Theodore J. -

The Scorecyr Cyrillic Font for Use in Score Date: January 18, 2004 Version: 1.01 Author: Jan De Kloe

1 Title: The ScoreCyr Cyrillic font for use in Score Date: January 18, 2004 Version: 1.01 Author: Jan de Kloe Introduction The font ScoreCyr was assembled from an existing industry font and adapted for use in Score by Matanya Ophee. This is a description of the font’s characters and how to use them. Use of the font is based on a Standard Russian keyboard which has different layout than a Latin keyboard. To use the font conveniently you either need a Russian keyboard1 or use SipText with the Cyrillic extension. Without a Russian keyboard, working with this font is cumbersome but not impossible, and this document is a help. The SipText program shows a Russian Keyboard on the screen and it can be used as a layout help, or keys can be pushed with the mouse. In this document, Cyrillic characters are shown in Arial Bold to distinguish the script from Latin characters. The font How to use the font There is no phonetic or visual correspondence between Latin and Cyrillic keyboards. On top of that, Score does not show the Cyrillic graphic representation of text and it is not until printing that the user sees the result of Cyrillic text editing. Also, there are some common characters like comma and period for which the font has no provision without adaptation of FONTINIT.PSC and the simplest alternative is to switch to a Latin font such as Times-Roman for those characters. Given here is the modern Russian alphabet. The transliteration is according to the “modified Library of Congress” standard.