Regional Phonological Variants in Louisiana Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interdental Fricatives in Cajun English

Language Variation and Change, 10 (1998), 245-261. Printed in the U.S.A. © 1999 Cambridge University Press 0954-3945/99 $9.50 Let's tink about dat: Interdental fricatives in Cajun English SYLVIE DUBOIS Louisiana State University BARBARA M. HORVATH University of Sydney ABSTRACT The English of bilingual Cajuns living in southern Louisiana has been pejoratively depicted as an accented English; foremost among the stereotypes of Cajun English is the use of tink and dat for think and that. We present a variationist study of/9/ and /d/ in the speech of bilingual Cajuns in St. Landry Parish. The results show a complex interrelationship of age, gender, and social network. One of the major findings is a v-shaped age pattern rather than the regular generational model that is expected. The older generation use more of the dental variants [t,d] than all others, the middle-aged dramatically decrease their use, but the young show a level of usage closer to the old generation. The change is attributed to both language attri- tion and the blossoming of the Cajun cultural renaissance. Interestingly, neither young men in open networks nor women of all ages in open networks follow the v-shaped age pattern. In addition, they show opposite directions of change: men in open networks lead the change to [d], whereas women in open networks drop the dental variants of [t,d] almost entirely. The variety of English spoken by people of Acadian descent (called Cajuns) in southern Louisiana has been the subject of pejorative comment for a long time. -

Prevocalic T-Glottaling Across Word Boundaries in Midland American

hon la Laboratory Phonology Kaźmierski, K. 2020 Prevocalic t-glottaling across word boundaries lab Journal of the Association for in Midland American English. Laboratory Phonology: Journal of Laboratory Phonology phon the Association for Laboratory Phonology 11(1): 13, pp. 1–23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/labphon.271 JOURNAL ARTICLE Prevocalic t-glottaling across word boundaries in Midland American English Kamil Kaźmierski Department of Contemporary English Language, Faculty of English at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, PL [email protected] Rates of t-glottaling across word boundaries in both preconsonantal and prevocalic contexts have recently been claimed to be positively correlated with the frequency of occurrence of a given word in preconsonantal contexts (Eddington & Channer, 2010). Words typically followed by consonants have been argued to have their final /t/s glottaled more often than words less frequently followed by consonants. This paper includes a number of ‘internal’ and ‘external’ predictors in a mixed-effects logistic regression model and has two goals: (1) to replicate the positive correlation of the frequency of occurrence of a word in preconsonantal contexts (its ‘contextual frequency’) with its rates of t-glottaling in both preconsonantal and prevocalic contexts postulated by Eddington and Channer (2010), and (2) to quantify the factors influencing the likelihood of t-glottaling across word boundaries in Midland American English. The effect of contextual frequency has been confirmed. This result is argued to support a hybrid view of phonological storage and processing, one including both abstract and exemplar representations. T-glottaling has also been found to be negatively correlated with bigram frequency and speech rate deviation, while positively correlated with young age in female speakers. -

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Commented

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Commented Translation of a Specialized Text Tomáš Šaroun Bachelor Thesis 2019 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracoval samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využil, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č.121/2000Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Beru na vědomí, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách a o změně a doplnění dalších zákonů (zákon o vysokých školách), ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a směrnicí Univerzity Pardubice č. 9/2012, bude práce zveřejněna v Univerzitní knihovně a prostřednictvím Digitální knihovny Univerzity Pardubice. V Pardubicích dne 17. 06. 2019 Tomáš Šaroun Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. Eva Nováková for her valuable advice, guidance, and patience. Additionally, I would like to thank my dear and loving family for continuous support and encouragement throughout my studies. ANNOTATION This bachelor thesis deals with various aspects of translating specialized texts from English to Czech. The first chapter contains definitions of stylistics and offers two points of view on the topic as are differently perceived by English and Czech scholars. -

Phonics Spelling Words Grade K 1 2.CA

Benchmark Advance Grade 1 Phonics Skills and Spelling Words Unit Week Phonics Spiral Review Spelling Words had, has, pack, ran, see, she, back, cap, sack, 1 Short a N/A pans Short i; 1 2 Short a big, him, hit, kick, kids, lid, little, you, fit, lips Plural Nouns Short o; box, doll, hot, jump, lock, mop, one, rock, 3 Short i Double Final Consonants tops, cots ten, jet, fed, neck, let, mess, look, are, beg, 1 Short e Short o sell Short u; come, cup, duck, dull, here, nut, rug, cub, sun, 2 2 Short e Inflectional Ending -s cuff class, clock, flat, glad, plan, put, what, slip, 3 l-Blends Short u black, plums r-Blends: br, cr, dr, fr, gr, pr, tr; brim, crab, trim, went, frog, drip, grass, prop, 1 l-Blends Singular Possessives trip, now s-Blends: sk, sl, sm, sn, sp, st, sw; skip, step, skin, smell, out, was, spin, sled, 3 2 r-Blends Contractions with ’s spot, slip Final Consonant Blends: nd, nk, nt, mp, st; jump, and, pink, hand, nest, went, who, good, 3 s-Blends Inflectional Ending -ed trunk, best Consonant Digraphs th, sh, ng; bath, bring, our, shop, shut, these, thing, 1 Final Consonant Blends nd, nk, nt, mp, st Inflectional Ending -ing wish, this, rang Consonant Digraphs ch, tch, wh; Consonant Digraphs chop, lunch, catch, check, once, when, whiff, 4 2 Closed Syllables th, sh, ng much, match, hurt Three-Letter Blends scr, spl, spr, squ, str; split, strap, scrub, squid, stretch, scratch, 3 Consonant Digraphs ch, tch, wh Plurals (-es) because, when, sprint, squish take, made, came, plate, brave, game, right, 1 Long a (final -e) Three-Letter -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

Quantifying Dimensions of the Vowel Space in Patients with Schizophrenia and Controls

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Quantifying Dimensions of the Vowel Space in Patients with Schizophrenia and Controls Elizabeth Maneval Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Phonetics and Phonology Commons Recommended Citation Maneval, Elizabeth, "Quantifying Dimensions of the Vowel Space in Patients with Schizophrenia and Controls" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1660. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1660 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincerest gratitude to my advisor, Anya Hogoboom, for her patience, insight, and unwavering support during every step of this project. Without her constant encouragement, I never would have completed this thesis. Thanks to Kate Harrigan for her assistance in conceptualizing approaches for analyzing the data. Thanks to Jacob Adams for his tireless work on troubleshooting with the coding involved in FAVE to make this project a reality. Thanks to the William & Mary Linguistics Research Group for their supportive and constructive feedback and ideas as this project progressed. Additional thanks to my family and friends for their grounding support and input on the various iterations of this project. Abstract The speech of patients with schizophrenia has been characterized as being aprosodic, or lacking pitch variation. Recent research on linguistic aspects of schizophrenia has looked at the vowel space to determine if there is some correlation between acoustic aspects of speech and patient status (Compton et al. -

The Rise of Canadian Raising of /Au/ in New Orleans English Katie Carmichael

The rise of Canadian raising of /au/ in New Orleans English Katie Carmichael Citation: The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 147, 554 (2020); doi: 10.1121/10.0000553 View online: https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0000553 View Table of Contents: https://asa.scitation.org/toc/jas/147/1 Published by the Acoustical Society of America ...................................ARTICLE The rise of Canadian raising of /au/ in New Orleans English Katie Carmichaela) Department of English, Virginia Tech, 181 Turner Street NW, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061, USA ABSTRACT: New Orleans English (NOE) has always stood out amongst Southern Englishes, since NOE speakers do not participate in the Southern vowel shift, and instead display features more commonly associated with New York City English. While these traditional features of NOE are on the decline, this study establishes the adoption of a new feature in the dialect that is similarly distinctive within the Gulf South: the pre-voiceless raising of the nucleus of /au/. Based on statistical analyses and consideration of the social context in post-Katrina New Orleans, this paper argues that this feature is a change in progress which appears to pre-date the demographic shifts following Hurricane Katrina, and which arose independently rather than due to contact with /au/-raising speakers. The social and phonetic findings in this paper converge to support arguments for the naturalness of raising in pre-voiceless environments, and for the likelihood of this feature being more widely adopted within the region. Moreover, the presence of Canadian raising of /au/ in NOE represents an additional way that the local dialect continues to diverge from patterns in the vowel systems found in nearby Southern dialects, and retain its uniqueness within the American South. -

Unit #1 Short a and I Unit #2 Short O and E Land Crop Plan Clock Stand

Unit #1 Short a and i Unit #2 Short o and e land crop plan clock stand drop act plot last block band flock grand test stamp spent sand left stick sled trip spend thing west lift tent swim desk list nest Unit #3 Short u sound Spelling Unit #4 /oi/ and /ou/ lunch boil until join buzz voice stuff oil dull point study soil uncle proud cuff loud under house cover cloud become sound nothing round month south love found none ground Unit #5 ew and oo Unit #7 Vowel-Consonant-e crew state news face drew pave knew flame threw skate chew plane loose slide school size smooth prize pool smile shoot close roof globe fool smoke balloon broke choose stone Unit #8 Long a: ai, ay Unit #9 Long e: ee, ea aid sheep chain street mail wheels paint cheese plain sweet main dream pail east laid treat paid mean pay peace tray real maybe leave lay stream always teacher away heat Unit #10 Long i: i, igh Unit #11 Long o: ow, oa, o night snow bright load find almost light row wild soak high window blind foam fight most sight flow kind goat sign throw knight float mild blow right below sigh soap Unit #13 sh,ch,tch,wr,ck Unit #14 Consonants /j/,/s/ shape change church age watch large father page wrap fence check space finish center sharp since mother price write ice catch dance chase pencil shall slice thick place wrote city Unit #15 Digraphs, Clusters Unit #16 Schwa Sound shook afraid flash around fresh upon splash never speech open stitch animal scratch ever switch about stretch again strong another string couple spring awake think over cloth asleep brook above Unit -

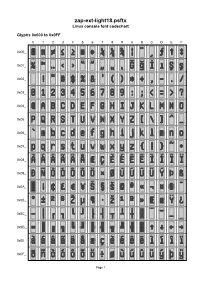

Zap-Ext-Light18.Psftx Linux Console Font Codechart

zap-ext-light18.psftx Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x013 U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Filename: zap-ext-light18.psftx PSF version: 1 0x014 U+203A SINGLE RIGHT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Glyph size: 8 × 18 pixels Glyph count: 512 0x015 U+201C LEFT DOUBLE QUOTATION Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) MARK, U+201F DOUBLE HIGH-REVERSED-9 QUOTATION MARK Unicode mappings 0x016 U+201D RIGHT DOUBLE 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT QUOTATION MARK, CHARACTER U+02EE MODIFIER LETTER DOUBLE 0x001 U+03C0 GREEK SMALL LETTER PI APOSTROPHE 0x002 U+2260 NOT EQUAL TO 0x017 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x003 U+2264 LESS-THAN OR EQUAL TO 0x018 U+2E42 DOUBLE LOW-REVERSED-9 0x004 U+2265 GREATER-THAN OR EQUAL QUOTATION MARK TO 0x019 U+2E41 REVERSED COMMA, 0x005 U+25A0 BLACK SQUARE, U+02CE MODIFIER LETTER LOW U+25AC BLACK RECTANGLE, GRAVE ACCENT U+25AE BLACK VERTICAL 0x01A U+011E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G RECTANGLE, WITH BREVE U+25FC BLACK MEDIUM SQUARE, U+25FE BLACK MEDIUM SMALL 0x01B U+011F LATIN SMALL LETTER G SQUARE, WITH BREVE U+2B1B BLACK LARGE SQUARE, 0x01C U+0130 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I U+220E END OF PROOF WITH DOT ABOVE 0x006 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01D U+0131 LATIN SMALL LETTER U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT, -

Acoustic Analysis of High Vowels in the Louisiana French of Terrebonne Parish

Acoustic analysis of high vowels in the Louisiana French of Terrebonne Parish Kelly Kasper-Cushmana∗ and Daniel Dakotaa a Department of Linguistics, Indiana University, 1020 E Kirkwood Ave, Bloomington, IN 47405, U.S.A. Abstract This study investigates high vowel laxing in the Louisiana French of the Lafourche Basin. Unlike Canadian French, in which the high vowels /i, y, u/ are traditionally described as undergoing laxing (to [I, Y, U]) in word-final syllables closed by any consonant other than a voiced fricative (see Poliquin 2006), Oukada (1977) states that in the Louisiana French of Lafourche Parish, any coda consonant will trigger high vowel laxing of /i/; he excludes both /y/ and /u/ from his discussion of high vowel laxing. The current study analyzes tokens of /i, y, u/ from pre-recorded interviews with three older male speakers from Terrebonne Parish. We measured the first and second formants and duration for high vowel tokens produced in four phonetic environments, crossing syllable type (open vs. closed) by consonant type (voiced fricative vs. any consonant other than a voiced fricative). Results of the acoustic analysis show optional laxing for /i/ and /y/ and corroborate the finding that high vowels undergo laxing in word-final closed syllables, regardless of consonant type. Data for /u/ show that the results vary widely by speaker, with the dominant pattern (shown by two out of three speakers) that of lowering and backing in the vowel space of closed syllable tokens. Duration data prove inconclusive, likely due to the effects of stress. The formant data published here constitute the first acoustic description of high vowels for any variety of Louisiana French and lay the groundwork for future study on these endangered varieties. -

The Survival of French Culture in South Louisiana by Barry Jean Ancelet

The Survival of French Culture in South Louisiana by Barry Jean Ancelet "What's your name? Where're you from? Who's your daddy?" When Barry j ean Ancelet - a native of Louisiana you first meet someone from south Louisiana, these are the questions where he grew up with French as his first language- received his Master 's Degree in you will probably hear. And you have to answer them before you can f olklore from Indiana University and his get along about your business. They are not rhetorical questions but doctorate in Creole Studies at the Universite quite serious ones designed to elicit information which helps to place de Provence. He is currently Director of Folklore Programs, Center for Louisiana you in the world of the Cajuns and Creoles. If you are from the inside, Studies, University of So uthwestern they want to know where you fit; if from the outside, they want to Louisiana. know how you got in and why. Such concerns could be thought of as xenophobic, but they are not. Rather they are simply part of a ritual to establish relationships - one which is used by a people whose history of tragedy and turmoil has taught them to be careful. Such questions function as boots for a people used to high water. Young and old perform during Cajun Mardi The French founded Louisiana in 1699. At first there were just a few Gras at Fred's Lounge in Mamou, Louisiana. forts perched precariously along the rivers of the frontier. Eventually, Photo by Philip Gould 47 however, there developed a society of French colonials. -

Universitat Pompeu Fabra Departament De Traducció I

Universitat Pompeu Fabra Departament de Traducció i Ciències del Llenguatge Programa Oficial de Doctorat Pluricentric dubbing in French and Spanish The translation of linguistic variation and prefabricated orality in films Presentat per Pascale Trencia Supervisió del projecte per Dra. Victòria Alsina, Dra. Jenny Brumme i Dra. Kristin Reinke Barcelona, setembre de 2019 Dedicatòria i Agraïments A mis padres, Guy y Lise, a mi hermana Marion, a Guillermo, a mis directoras, Vicky, Jenny y Kristin, y a todos los que han cruzado mi camino durante estos cincos años de estudios doctorales. Esta tesis lleva un poco de cada uno de vosotros. Resum El present estudi examina com es tradueix el discurs fílmic, especialment els elements marcadors de la variació lingüística, al francès i al castellà, dues llengües pluricèntriques, és a dir, llengües que tenen més d’un centre normatiu. El fet que diverses nacions adoptin mesures per promoure la indústria nacional del doblatge, en general per motius econòmics i culturals, en ocasions porta a duplicar les varietats de doblatge. Per tant, una qüestió clau és saber com es comparen aquestes versions doblades i com aconsegueixen transmetre la variació lingüística i la oralitat prefabricada a través de les seves respectives traduccions. L’objectiu d’aquesta investigació consisteix a examinar quines són les principals diferències i similituds entre el discurs fílmic doblat de Quebec i de França (per al francés) i d’Espanya i Amèrica Llatina (per a l’espanyol), sobre la base d’un estudi de la pel·lícula Death Proof (2007) de Quentin Tarantino. Aquesta pel·lícula va ser seleccionada pel seu alt nivell de variació lingüística i la importància que Tarantino dóna a la llengua (no estàndard) de les seves pel·lícules.