Ikegobo to the Iyoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

1 Ancient America and Africa

NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 2 CHAPTER 1 Ancient America and Africa Portuguese troops storm Tangiers in Morocco in 1471 as part of the ongoing struggle between Christianity and Islam in the mid-fifteenth century Mediterranean world. (The Art Archive/Pastrana Church, Spain/Dagli Orti) American Stories Four Women’s Lives Highlight the Convergence of Three Continents In what historians call the “early modern period” of world history—roughly the fif- teenth to the seventeenth century, when peoples from different regions of the earth came into close contact with each other—four women played key roles in the con- vergence and clash of societies from Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Their lives highlight some of this chapter’s major themes, which developed in an era when the people of three continents began to encounter each other and the shape of the mod- ern world began to take form. 2 NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 3 CHAPTER OUTLINE Born in 1451, Isabella of Castile was a banner bearer for reconquista—the cen- The Peoples of America turies-long Christian crusade to expel the Muslim rulers who had controlled Spain for Before Columbus centuries. Pious and charitable, the queen of Castile married Ferdinand, the king of Migration to the Americas Aragon, in 1469.The union of their kingdoms forged a stronger Christian Spain now Hunters, Farmers, and prepared to realize a new religious and military vision. Eleven years later, after ending Environmental Factors hostilities with Portugal, Isabella and Ferdinand began consolidating their power. -

Igue Festival and the British Invasion of Benin 1897: the Violation of a People’S Culture and Sovereignty

Vol. 6(1), pp. 1-5, March, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2013.0170 African Journal of History and Culture ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Full Length Research Paper Igue festival and the British invasion of Benin 1897: The violation of a people’s culture and sovereignty Charles .O. Osarumwense Department of History and International Studies, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Accepted 18 December, 2013 The Benin Kingdom was a sovereign state in pre-colonial West Africa. Sovereign in the sense that the Kingdom conducted and coordinated its internal and external affairs with its well structured political, social-cultural and economic institutions. One remarkable aspect of the Benin culture was the Igue festival. The festival was unique in the sense that it was a period when the Oba embarks on spiritual cleansing and prayers to departed ancestors for continued protection and growth of the land. The period of the festival was uncompromising and was spiritually adhered to. It was during this period that the British attempted to visit the Oba. This attempted visit to the land was declined by the Oba. An imposition of the visit by the British Crown resulted in the ambushed and killing of British officers. This incident marked the road map to the British invasion of the Kingdom in 1897. This study presents the sovereign nature of the Benin Kingdom, its social-cultural and economic uniqueness rooted in the belief and respect of deities. The paper further argues that the event of 1897 was a clear cut violation of the sovereignty, culture and territorial rights of the Benin Kingdom under a crooked agreement called the Gallwey Treaty of 1892. -

The Worlds of the Fifteenth Century

c h a p t e r t h i r t e e n The Worlds of the Fifteenth Century During 2005, Chinese authorities marked the 600th anniversary of the initial launching of their country’s massive maritime expeditions in 1405. Some eighty-seven years before Columbus sailed across the Atlantic with three small ships and a crew of about ninety men, the Chinese admiral Zheng He had captained a fleet of more than 300 ships and a crew numbering some 27,000 people, which brought a Chinese naval presence into the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean as far as the East African coast. Now in 2005, China was celebrating. Public ceremonies, books, magazine articles, two television documentaries, an international symposium, a stamp in honor of Zheng He—all of this and more was part of a yearlong remembrance of these remarkable voyages. Given China’s recent engagement with the larger world, Chinese authorities sought to use Zheng He as a symbol of their country’s expanding, but peaceful, role on the international stage. Until recently, however, his achievement was barely noticed in China’s collective memory, and for six centuries Zheng He had been largely forgotten or ignored. Columbus, on the other hand, had long been highly visible in the West, celebrated as a cultural hero and more recently harshly criticized as an imperialist, but certainly remembered. The voyages of both of these fifteenth-century mariners were pregnant with meaning for world history. Why were they remembered so differently in the countries of their origin? The fifteenth century, during which both Zheng He and Columbus undertook their momentous expeditions, proved in retrospect to mark a major turning point in the human story .At the time, of course, no one was aware of it. -

FINAL De Young Higlights Large Print

FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO DE YOUNG MUSEUM HIGHLIGHTS TOUR Audio tour script WRITER/PRODUCER: FRANCES HOMAN JUE SOUND DESIGNER: PETER DUNNE NARRATOR: TBD 1 De Young Highlights Tour American Stops: Stop 302 La Carreta de la Muerte/Chariot of Death, ca. 1900, 1995.23a-e Stop 304 The Freake-Gibbs Painter, David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason, 1670 1979.7.3 Stop 308 Joshua Johnson, Letitia Grace McCurdy, ca. 1800-1802, 1995.22 Stop 311 Thomas Hovenden, The Last Moments of John Brown, 1979.7.60 Stop 371 Horace Pippin, Trial of John Brown, 1942, 1979.7.82 Stop 370 Hiram Powers, Greek Slave, ca. 1873, 2016.1 Stop 380 James McNeil Whistler, The Gold Scab: Eruption in Filthy Lucre, 1879 1977.11 Stop 325 Frederic Edwin Church, Rainy Season in the Tropics, 1866, 1970.9 Stop 321 William Michael Harnett, After the Hunt, 1885, 1940.93 Stop 330 Mary Cassatt, The Artist’s Mother, ca. 1889, 1979.35 Modern and Contemporary Stops Stop 331 Chiura Obata, Mother Earth, 1912/1922/1928, 200.71.2 2 Stop 337 Georgia O’Keeffe, Petunias, 1950.55 Stop 343 Grant Wood, Dinner for Threshers, 1934, 1979.7.105 Stop 345 Aaron Douglas, Aspiration, 1936, 1977.84 Stop 346 Richard Diebenkorn, Berkeley No. 3, 1953, 2003.25.3 Stop 245 Larry Rivers, The Last Civil War Veteran, 1961, 2009.13 Stop 375 Frank Stella, Lettre sur les aveugles II, 1974, 2013.1 Stop 368 Ruth Asawa Sculpture installation in Education Tower Stop 385 Louise Nevelson, Sky Cathedral’s Presence I , 1959-62 African art Stop 211 Dogon figure of an Ancestor or Deity, 2003.65 Stop 215 Hornbill Mask, 73.9 Stop 216 Oath Taking Figure, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kongo, 1986.16.1 Stop 221 Benin plaque, Nigeria, Kingdom of Benin, 1980.31 Stop 222 Drum, Ghana, Fante, 1980.73 Stop 223 Kane Kwei,Coffin in the shape of a cocoa pod, ca. -

UK Rejection of Restitution of Artefacts: Confirmation Or Surprise?

25.05.2019 FEATURE ARTICLE UK Rejection Of Restitution Of Artefacts: Confirmation Or Surprise? By Kwame Opoku, Dr. ‘’Truth must be repeated constantly, because error is being repeatedly preached round about all the few, but by the masses. In the periodicals and encyclopaedias, in schools and universities, everywhe confident and comfortable in the feeling that it has the majority on its side.” Johann Wolfgang von G The United Kingdom Secretary for Culture is reported as having declared: “ Never mind the argume thing, let’s argue about how it gets to be seen ”. (2) Mr. Jeremy Wright whose pronouncements on o caused surprise made this statement in response to The Times with respect to the debate on restitutio The Minister argued that if artefacts were returned to their countries of origin, there would be no on see multiple objects:‘ if you followed the logic of restitution to its logical conclusion ,according to W ‘no single points where people can see multiple things’ Wright also stated that the United Kingdom Crown of Tewodros II, looted laws to enable restitution of cultural artefacts to the various countries. at Maqdala, Ethiopia in 1868, now in Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom. ‘His argument seemed to rely on the tired misconception that there would be nothing much left in our museums and “no single points wher things” if restitution was allowed. This kind of thinking flies in the face of the informed conversation about decolonisation, restitution and repatriation that is taking place in at government level in many countries in Europe. ‘(3) What Jeremy Wright is attempting to do is to revive the long discredited universal museum argument that artefacts of different cultures are understood when they are all gathered at one museum such as the British Museum. -

Kingdom of Benin Benin Was an Influential City-State in Northwest

1 Kingdom of Benin Benin was an influential city-state in northwest Africa generally from the 15th to 17th century. It was founded by the Edo or Bini people in the 13thcentury, and by the early 14th century a royal court was in place. It was always ruled by a powerful king who was usually a former war leader. The kings, however, later became a more religious figure. The kingdom has been though to extend throughout what is presently southern Nigeria. One of its most successful kings was Ozoula. During his reign, from about1480 to 1504, Benin established many commercial and diplomatic relations with Portugal. The kingdom participated in a lot of trade with Europe. Some of the goods they traded included palm oil, ivory, pepper, and textiles. Another industry Benin took place in was the slave trade. Mostly POW's (prisoners of war)and women were traded, but in the early years, men of the tribe were also given away. Gradually, the power of the kingdom decreased as the 18th and 19th centuries passed. Eventually, in 1897, the area was annexed to British Nigeria. While tribesmen still led the area, the real control was in the hands of the Europeans. One of the richest arts that originated in Africa are some of the hand cast bronzes that came out of the kingdom of Benin. These became known as the Benin Bronzes. The casting of brass was strictly a royal art and anyone found casting brass without royal permission was faced with execution. Whenever a king or a major figure died, a beautiful commemorative head was cast out of bronze in his honor. -

The African Bronze Art Culture of the Bight of Benin and Its Influence on Modern Art

The African Bronze Art Culture of the Bight of Benin and its Influence on Modern Art This article is dedicated to Dr. Leroy Bynum, the pioneer Dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at Albany State University (2006-2014), for his 22-years of devoted service to this institution. Emmanuel Konde Department of History and Political Science Introduction There are two “Benins” in West Africa. Both straddle the coastline area known as the Bight of Benin that encompasses, among other nations, Nigeria and the Republic of Benin. One is the former Kingdom of Benin in present-day Nigeria; the other a successor state of the former Kingdom of Dahomey, now called the Republic of Benin. These kingdoms were the products of two significant waves of social change that dominated Africa’s history from the earliest times to the 19th century: migration and state formation. Migration and state formation trends in Africa’s precolonial history often intersected and interwove. As John Lamphear observed, these trends involved internal population movements “that typically led to the formation of new societies, linguistic groups, and states.”1 Historical evidence suggests that the rise of the two Benin kingdoms was influenced by similar social forces and that the founders of these kingdoms shared a strong cultural affinity. Consequently, both Benins developed a sculptural art form in bronze casting of high quality that probably issued from the same culture complex and shared experiences. If the peoples of the kingdoms of Benin and Dahomey were not originally the same people who were eventually separated by migrations occasioned by the struggles of state formation, at least a vibrant and dynamic culture contact between them culminated in a diffusion of arts and crafts that ultimately resulted in striking similarities between their bronze sculptures. -

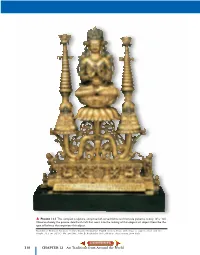

318 CHAPTER 12 Art Traditions from Around the World CHAPTER 12 Art Traditions from Around the World Rt Is More Than Just Objects and Images

ᮡ 1 FIGURE 12.1 This complex sculpture, composed of curved forms and intricate patterns, is only 12 /4 Љ tall. Observe closely the precise detail and craft that went into the making of this elegant art object. Describe the type of balance that organizes this object. Kashmir or Northern Pakistan. Crowned Buddha Shakyamuni. Eighth century. Brass with inlays of copper, silver, and zinc. 1 Height: 31.1 cm (12 ր4”). Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection. Asia Society: New York. 318 CHAPTER 12 Art Traditions from Around the World CHAPTER 12 Art Traditions from Around the World rt is more than just objects and images. It is a visual Astory of a people and their culture. It reveals their feelings, views, and beliefs. In a sense, art history mirrors the history of the world. It is a window on the past and the many cultures that enrich our lives. In this chapter, you will: Describe general characteristics in artworks from a variety of cultures. Compare and contrast historical styles, identifying trends and themes. Describe art traditions from cultures around the world. Figure 12.1 is an ancient object of worship from Kashmir or Northern Pakistan. The subject is Buddha Shakyamuni, spir- itual leader of the Shakya clan of Buddhism. His hands are positioned in the gesture of teaching as he sits peacefully on a lotus flower rising above the water on a thick stem. To the right and left of the base are small female and male figures. Art historians believe that these figures represent the donors of the sculpture. -

THE MILITARY SYSTEM of BENIN KINGDOM, C.1440 - 1897

THE MILITARY SYSTEM OF BENIN KINGDOM, c.1440 - 1897 THESIS in the Department of Philosophy and History submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Hamburg, Germany By OSARHIEME BENSON OSADOLOR, M. A. from Benin City, Nigeria Hamburg, 23 July, 2001 DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FIRST EXAMINER Professor Dr. Leonhard Harding Doctoral father (Professor für Geschichte Afrikas) Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg SECOND EXAMINER Professor Dr. Norbert Finzsch (Professor für Aussereuropäische Geschichte) Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg CHAIR Professor Dr. Arno Herzig Prodekan Fachbereich Philosophie und Geschichtswissenchaft Universität Hamburg DATE OF EXAMINATION (DISPUTATION) 23 July, 2001 ii DECLARATION I, Osarhieme Benson Osadolor, do hereby declare that I have written this doctoral thesis without assistance or help from any person(s), and that I did not consult any other sources and aid except the materials which have been acknowledged in the footnotes and bibliography. The passages from such books or maps used are identified in all my references. Hamburg, 20 December 2000 (signed) Osarhieme Benson Osadolor iii ABSTRACT The reforms introduced by Oba Ewuare the Great of Benin (c.1440-73) transformed the character of the kingdom of Benin. The reforms, calculated to eliminate rivalries between the Oba and the chiefs, established an effective political monopoly over the exertion of military power. They laid the foundation for the development of a military system which launched Benin on the path of its imperial expansion in the era of the warrior kings (c.1440-1600). The Oba emerged in supreme control, but power conflicts continued, leading to continuous administrative innovation and military reform during the period under study.