Thesis-Reclaiming the Past- How a Legacy Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Macgregor, a History of the World in 100 Objects

TERMINUS tom 15 (2013), z. 2 (27), s. 275–282 doi:10.4467/20843844TE.13.016.1573 www.ejournals.eu/Terminus NCEIL MA GREGOR, A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 100 OBJECTS, FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRINT IN OCTOBER 2010 BY ALLEN LANE IMPRINT OF PENGUIN BOOKS, PP. 640 Edition used for the review: Kindle Edition, 6 October 2011, Penguin KAJA SZYMAńSKA Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków Only stable, rich and powerful states can commission great art and architectu- re that, unlike text or language, can be instantly understood by anyone – a gre- at advantage in multilingual empires. Neil MacGregor1 The book A History of the World in 100 Objects is a result of a multi-plat- form BBC and British Museum joint enterprise released in 2010. It of- fered an innovative look at history and the role of a museum, and was a great success in popularising knowledge, and history in particular. The whole project involved 550 heritage partners and comprised several me- dia outlets: a six-month long series of daily broadcasts by BBC Radio 4, a website through which individual users and other institutions could also contribute, uploading objects of their own choice, and finally, the book to which this review specifically relates. The radio programme drew 4 million listeners and podcast downloads amounted to over 10 million during the 1 N. MacGregor, loc. 3542/9008. Publikacja objęta jest prawem autorskim. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Kopiowanie i rozpowszechnianie zabronione. Publikacja przeznaczona jedynie dla klientów indywidualnych. Zakaz rozpowszechniania i udostępniania w serwisach bibliotecznych 276 Kaja Szymańska following year (only just over 5.7 million from the UK). -

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

The British Museum Report and Accounts for the Year

The British Museum REPOrt AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 HC 400 £14.75 The British Museum REPOrt AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Museums and Galleries Act 1992 (c.44) S.9(8) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 12 July 2012 HC 400 London: The Stationery Office £14.75 The British Museum Account 2011-2012 © The British Museum (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The British Museum copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk ISBN: 9780102976199 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2481871 07/12 21557 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum The British Museum Account 2011-2012 Contents Page Trustees’ and Accounting Officer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 5 Constitution and operating environment 5 Governance statement 5 Subsidiaries 10 Friends’ organisations 10 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 10 To manage and research the collection more effectively 10 Collection 10 Conservation -

Barbara Blackmun Collection, EEPA 2016-012

Barbara Blackmun Collection, EEPA 2016-012 Eden Orelove October 2018 Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art National Museum of African Art P.O. Box 37012 MRC 708 Washington, DC 20013-7012 [email protected] http://africa.si.edu/collection/eliot-elisofon-photographic-archives/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Museum Objects, 1979-1994.................................................................... 4 Series 2: People, circa 1969-1994......................................................................... 71 Series 3: Ceremonies and Festivals, circa 1969-1994........................................... 89 Series 4: Landscape and Street -

The Parthenon Sculptures Sarah Pepin

BRIEFING PAPER Number 02075, 9 June 2017 By John Woodhouse and Sarah Pepin The Parthenon Sculptures Contents: 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 3. Ongoing controversy 4. Further reading www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Parthenon Sculptures Contents Summary 3 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 5 1.1 Early history 5 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 6 3. Ongoing controversy 7 3.1 Campaign groups in the UK 9 3.2 UK Government position 10 3.3 British Museum position 11 3.4 Greek Government action 14 3.5 UNESCO mediation 14 3.6 Parliamentary interest 15 4. Further reading 20 Contributing Authors: Diana Perks Attribution: Parthenon Sculptures, British Museum by Carole Radatto. Licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 9 June 2017 Summary This paper gives an outline of the more recent history of the Parthenon sculptures, their acquisition by the British Museum and the long-running debate about suggestions they be removed from the British Museum and returned to Athens. The Parthenon sculptures consist of marble, architecture and architectural sculpture from the Parthenon in Athens, acquired by Lord Elgin between 1799 and 1810. Often referred to as both the Elgin Marbles and the Parthenon marbles, “Parthenon sculptures” is the British Museum’s preferred term.1 Lord Elgin’s authority to obtain the sculptures was the subject of a Select Committee inquiry in 1816. It found they were legitimately acquired, and Parliament then voted the funds needed for the British Museum to acquire them later that year. -

The New Encyclopedia of Benin

Barbara Plankensteiner. Benin: Kings and Rituals. Gent: Snoeck, 2007. 535 pp. $85.00, cloth, ISBN 978-90-5349-626-8. Reviewed by Kate Ezra Published on H-AfrArts (December, 2008) Commissioned by Jean M. Borgatti (Clark Univeristy) The exhibition "Benin Kings and Rituals: This section of the catalog features 301 ob‐ Court Arts from Nigeria," organized by Barbara jects discussed in 205 entries by 19 authors. The Plankensteiner, is an extraordinary opportunity objects, all illustrated in full color, are drawn to see hundreds of masterworks of Benin art to‐ from twenty-five museums in Europe, the United gether in one place. It will be on view at the Art States, and Nigeria, and also include several Institute of Chicago, its only American venue, works privately owned by Oba Erediauwa and from July 10 to September 21, 2008. The colossal High Priest Osemwegie Ebohen of Benin City. exhibition catalog provides a permanent record Most of the international team of authors who of this remarkable exhibition and will soon be‐ wrote the catalog entries are renowned Benin come the essential reference work on Benin art, scholars; the others are Africanists who serve as culture, and history. The frst half of the book curators of collections that lent objects to the exhi‐ Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria, bition. A full half of the entries were written by edited by Barbara Plankensteiner, consists of Barbara Blackmun (forty-nine) , Kathy Curnow twenty-two essays by a world-class roster of schol‐ (twenty-six), Paula Ben-Amos Girshick (fourteen), ars on a broad range of topics and themes related and Joseph Nevadomsky (thirteen). -

Wikimedia with Liam Wyatt

Video Transcript 1 Liam Wyatt Wikimedia Lecture May 24, 2011 2:30 pm David Ferriero: Good afternoon. Thank you. I’m David Ferriero, I’m the Archivist of the United States and it is a great pleasure to welcome you to my house this afternoon. According to Alexa.com, the internet traffic ranking company, there are only six websites that internet users worldwide visit more often than Wikipedia: Google, Facebook, YouTube, Yahoo!, Blogger.com, and Baidu.com (the leading Chinese language search engine). In the States, it ranks sixth behind Amazon.com. Over the past few years, the National Archives has worked with many of these groups to make our holdings increasingly findable and accessible, our goal being to meet the people where they are. This past fall, we took the first step toward building a relationship with the “online encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” When we first began exploring the idea of a National Archives-Wikipedia relationship, Liam Wyatt was one of, was the one who pointed us in the right direction and put us in touch with the local DC-area Wikipedian community. Early in our correspondence, we were encouraged and inspired when Liam wrote that he could quote “quite confidently say that the potential for collaboration between NARA and the Wikimedia projects are both myriad and hugely valuable - in both directions.” I couldn’t agree more. Though many of us have been enthusiastic users of the Free Encyclopedia for years, this was our first foray into turning that enthusiasm into an ongoing relationship. As Kristen Albrittain and Jill James of the National Archives Social Media staff met with the DC Wikipedians, they explained the Archives’ commitment to the Open Government principles of transparency, participation, and collaboration and the ways in which projects like the Wikipedian in Residence could exemplify those values. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

![[2005] Decision](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7927/2005-decision-847927.webp)

[2005] Decision

Page 1 2 of 3 DOCUMENTS Attorney General v Trustees of the British Museum (Commission for Looted Art in Eu- rope intervening) Chancery Division [2005] EWHC 1089 (Ch), [2005] Ch 397 HEARING-DATES: 24, 27 May 2005 27 May 2005 CATCHWORDS: Charity - Disposal of asset - Power - Museum's collection including looted objects - Heir of previous owner having moral claim to their return - Statutory prohibition on museum disposing of objects in collection - Whether Attorney General or court having power to authorise return - Whether trustees having power to ignore limitation defence to effect return - British Museum Act 1963 (c 24), s. 3(4) (as amended by Museums and Galleries Act 1992 (c 44), s. 11(2), Sch. 8, Pt I, para 5(a)) HEADNOTE: The trustees of the British Museum considered a claim brought by the heirs of F that four old master drawings in the museum's collections had been the property of F and had been stolen from him by the Gestapo during the Nazi oc- cupation of Czechoslovakia. The trustees were sympathetic to the claim and asked the Attorney General to permit the restitution of the drawings to F's heirs on the ground that it was morally right to do so. There was a principle which permitted the Attorney General or the court to authorise a payment out of charity funds where there was a moral obliga- tion to make such a payment, however, the Attorney General was concerned that the prohibition in section 3(4) of the British Museum Act 1963 n1 on the disposal of objects comprised in the museum's collections prevented the application of that principle to authorise the restitution of the drawings. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

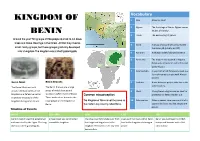

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

When Repatriation Doesn't Happen: Relationships Created Through Cultural Property Negotiations

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 2020 When Repatriation Doesn’t Happen: Relationships Created Through Cultural Property Negotiations Ellyn DeMuynck Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Museum Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons When Repatriation Doesn’t Happen: Relationships Created Through Cultural Property Negotiations __________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Denver __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ___________________ by Ellyn DeMuynck March 2020 Advisor: Christina Kreps Author: Ellyn DeMuynck Title: When Repatriation Doesn’t Happen: Relationships Created Through Cultural Property Negotiations Advisor: Christina Kreps Degree Date: March 2020 Abstract This thesis analyzes the discourse of repatriation in connection to the Encounters exhibition held by the National Museum of Australia in 2015. Indigenous Australian and Torres Strait Islander artifacts were loaned to the Australian museum by the British Museum. At the close of the exhibition, one item, the Gweagal shield, was claimed for repatriation. The repatriation request had not been approved at the time of this research. The Gweagal shield is a historically significant artifact for Indigenous and non- Indigenous Australians. Analysis takes into account the political economy of the two museums and situates the exhibition within the relevant museum policies. This thesis argues that, while the shield has not yet returned to Australia, the discussions about what a return would mean are part of the larger process of repatriation. It is during these discussions that the rights to material culture are negotiated.