Bring Me Sunshine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There Are 16 Primary and 2 Secondary

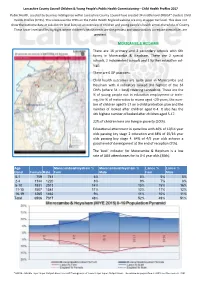

Lancashire County Council Children & Young People’s Public Health Commissioning—Child Health Profiles 2017 Public Health, assisted by Business Intelligence within Lancashire County Council have created 34 middle level (MSOA* cluster) Child Health Profiles (CHPs). This is because the CHPs on the Public Health England website are only at upper tier level. This does not show the outcome data at sub-district level but just an overview of children and young people’s health across the whole of County. These lower level profiles highlight where children’s health needs are the greatest and opportunities to reduce inequalities are greatest. MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There are 16 primary and 2 secondary schools with 6th forms in Morecambe & Heysham. There are 2 special schools, 2 independent schools and 1 further education col- lege. There are 6 GP practices. Child health outcomes are quite poor in Morecambe and Heysham with 4 indicators ranked 3rd highest of the 34 CHPs (where 34 = best) covering Lancashire. These are the % of young people not in education employment or train- ing, the % of maternities to mums aged <20 years, the num- ber of children aged 5-17 on a child protection plan and the number of looked after children aged 0-4. It also has the 4th highest number of looked after children aged 5-17. 22% of children here are living in poverty (10th). Educational attainment in quite low with 46% of 10/11 year olds passing key stage 2 education and 48% of 15/16 year olds passing key stage 4. 64% of 4/5 year olds achieve a good level of development at the end of reception (7th). -

CYCLING for ALL CONTENTS Route 1: the Lune Valley

LANCASTER, MORECAMBE & THE LUNE VALLEY IN OUR CITY, COAST & COUNTRYSIDE CYCLING FOR ALL CONTENTS Route 1: The Lune Valley..................................................................................4 Route 2: The Lune Estuary ..............................................................................6 Route 3: Tidal Trails ..........................................................................................8 Route 4: Journey to the Sea............................................................................10 Route 5: Brief Encounters by Bike..................................................................11 Route 6: Halton and the Bay ..........................................................................12 Cycling Online ................................................................................................14 2 WELCOME TO CYCLING FOR ALL The District is rightly proud of its extensive cycling network - the largest in Lancashire! We're equally proud that so many people - local and visitors alike - enjoy using the whole range of routes through our wonderful city, coast and countryside. Lancaster is one of just six places in the country to be named a 'cycling demonstration' town and we hope this will encourage even more of us to get on our bikes and enjoy all the benefits cycling brings. To make it even easier for people to cycle Lancaster City Council has produced this helpful guide, providing at-a-glance information about six great rides for you, your friends and family to enjoy. Whether you've never ridden -

Download the Report Item 4

BOROUGH COUNCIL OF WELLINGBOROUGH AGENDA ITEM 4 Development Committee 17 February 2020 Report of the Principal Planning Manager Local listing of the Roundhouse and proposed Article 4 Direction 1 Purpose of report For the committee to consider and approve the designation of the Roundhouse (or number 2 engine shed) as a locally listed building and for the committee to also approve an application for the addition of an Article 4(1) direction to the building in order to remove permitted development rights and prevent unauthorised demolition. 2 Executive summary 2.1 The Roundhouse is a railway locomotive engine shed built in 1872 by the Midland Railway. There is some concern locally that the building could be demolished and should be protected. It was not considered by English Heritage to be worthy of national listing but it is considered by the council to be worthy of local listing. 2.2 Local listing does not protect the building from demolition but is a material consideration in a planning application. 2.3 An article 4(1) direction would be required to be in place to remove the permitted development rights of the owner. In this case it would require the owner to seek planning permission for the partial or total demolition of the building. 3 Appendices Appendix 1 – Site location plan Appendix 2 – Photos of site Appendix 3 – Historic mapping Appendix 4 – Historic England report for listing Appendix 5 – Local list criteria 4 Proposed action: 4.1 The committee is invited to APPROVE that the Roundhouse is locally listed and to APPROVE that an article 4 (1) direction can be made. -

Peat Database Results Lancashire

Bare, Lancashire Record ID 236 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 443 649 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat layer (often <1 m thick, hard, consolidated, dry, laminated deposit). Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Boreholes SD46 SW/52-54 Depth of deposit 14C ages available -10 m OD No Notes Bibliographic reference Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. 1998 'Geology of the country around Lancaster', Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheet 59 (England and Wales), . Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 31 Bare, Lancashire Record ID 237 Authors Year Crofton, A. 1876 Location description Deposit location SD 445 651 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat horizon resting on blue organic clay. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Crofton (1876) referred to in Brandon et al (1998). Possibly same layer as mentioned by Reade (1904). Bibliographic reference Crofton, A. 1876 'Drift, peat etc. of Heysman [Heysham], Morecambe Bay', Transactions of the Manchester Geological Society, 14, 152-154. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 2 of 31 Carnforth coastal area, Lancashire Record ID 245 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 4879 6987 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Coastal peat up to 4.9 m thick. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Borehole SD 46 NE/1 Depth of deposit 14C ages available Varying from near-surface to at-surface. -

Part 3 of the Bibliography Catalogue

Bibliography - L&NWR Society Periodicals Part 3 - Railway Magazine Registered Charity - L&NWRSociety No. 1110210 Copyright LNWR Society 2012 Title Year Volume Page Railway Magazine Photos. Junction at Craven Arms Photos. Tyne-Mersey Power. Lime Street, Diggle 138 Why and Wherefore. Soho Road station 465 Recent Work by British Express Locomotives Inc. Photo. 2-4-0 No.419 Zillah 1897 01/07 20 Some Racing Runs and Trial Trips. 1. The Race to Edinburgh 1888 - The Last Day 1897 01/07 39 What Our Railways are Doing. Presentation to F.Harrison from Guards 1897 01/07 90 What Our Railways are Doing. Trains over 50 mph 1897 01/07 90 Pertinent Paragraphs. Jubilee of 'Cornwall' 1897 01/07 94 Engine Drivers and their Duties by C.J.Bowen Cooke. Describes Rugby with photos at the 1897 01/08 113 Photo.shed. 'Queen Empress' on corridor dining train 1897 01/08 133 Some Railway Myths. Inc The Bloomers, with photo and Precedent 1897 01/08 160 Petroleum Fuel for Locomotives. Inc 0-4-0WT photo. 1897 01/08 170 What The Railways are Doing. Services to Greenore. 1897 01/08 183 Pertinent Paragraphs. 'Jubilee' class 1897 01/08 187 Pertinent Paragraphs. List of 100 mile runs without a stop 1897 01/08 190 Interview Sir F.Harrison. Gen.Manager .Inc photos F.Harrison, Lord Stalbridge,F.Ree, 1897 01/09 193 TheR.Turnbull Euston Audit Office. J.Partington Chief of Audit Dept.LNW. Inc photos. 1897 01/09 245 24 Hours at a Railway Junction. Willesden (V.L.Whitchurch) 1897 01/09 263 What The Railways are Doing. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Model Railways

Toy Trains, and Model Railways The Clockwork Era, 1952-55 The genesis of a lifetime’s hobby was, as usual at that time, a Hornby ‘O’ gauge clockwork train set, purchased probably for my birthday in 1952, or at Xmas later that year. This comprised a dark red 0-4-0 tank locomotive and two 4-wheeled carriages, running on jointed tinplate track which I took great pleasure in routing sinuously around the table and chairs, on the floor of our living room at Fenton Avenue, Staines, getting under everyone’s feet. This system was expanded to include various goods wagons, a level crossing, signals, a tinplate station, a further coach, and lastly an additional engine of the same 0-4-0 type, but this time enamelled in black livery. A broken mainspring, no doubt due to over-enthusiastic winding, was a problem requiring fiddly replacement by my father. This collection was probably sold to the Atkins at no 24, who had twin boys a few years younger than me. They also had all my old ‘Dinky Toys’ which too would have been worth something these days! However they were probably very ‘well-used’ and without their boxes, so perhaps not. “OO” gauge electric trains 1956-58 The replacement for my ‘O’ gauge system came in the form of a Hornby Dublo “Royal Scot” train set. I think this cost the princely sum of 63 shillings (£3.15) at a time when the average take-home pay was around £9 per week. Nowadays a similar set would be around £120, so the relative amounts are not greatly different. -

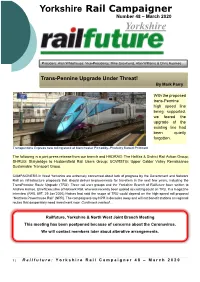

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 48 – March 2020

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 48 – March 2020 Yorkshire President: Alan Whitehouse: Vice-Presidents: Mike Crowhurst, Alan Williams & Chris Hyomes Trans-Pennine Upgrade Under Threat! By Mark Parry With the proposed trans-Pennine high speed line being supported, we feared the upgrade of the existing line had been quietly forgotten. Transpennine Express new rolling stock at Manchester Piccadilly–Photo by Robert Pritchard The following is a joint press release from our branch and HADRAG: The Halifax & District Rail Action Group; SHRUG: Stalybridge to Huddersfield Rail Users Group; UCVRSTG: Upper Calder Valley Renaissance Sustainable Transport Group. CAMPAIGNERS in West Yorkshire are extremely concerned about lack of progress by the Government and Network Rail on infrastructure proposals that should deliver improvements for travellers in the next few years, including the TransPennine Route Upgrade (TRU). Three rail user groups and the Yorkshire Branch of Railfuture have written to Andrew Haines, Chief Executive of Network Rail, who was recently been quoted as casting doubt on TRU. In a magazine interview (RAIL 897, 29 Jan’2020) Haines had said the scope of TRU could depend on the high-speed rail proposal “Northern Powerhouse Rail” (NPR). The campaigners say NPR is decades away and will not benefit stations on regional routes that desperately need investment now. Continued overleaf… Railfuture, Yorkshire & North West Joint Branch Meeting This meeting has been postponed because of concerns about the Coronavirus. We will contact members later about alterative arrangements. 1 | Railfuture: Yorkshire Rail Campaigner 4 8 – M a r c h 2020 The campaigners have also written to Secretary of State for Transport Grant Shapps MP, and to the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, calling for urgent, overdue projects to go ahead without further delay. -

Lancashire and Cumbria Route Utilisation Strategy August 2008

Lancashire and Cumbria Route Utilisation Strategy August 2008 Foreword I am delighted to present Network Rail’s Route There are currently aspirations for a service Utilisation Strategy (RUS) for Lancashire and between Southport, Preston and Ormskirk. Cumbria, which considers issues affecting This is partly facilitated by work to enhance the railway in this part of the country over the track and signalling between Preston and next decade and gives a view on longer-term Ormskirk, which will allow a standard hourly issues in the years beyond. service pattern with improved journey times but without the need for more rolling stock. Getting to this stage has involved following a now well-established process. However, there Services into Sellafield during peak hours are two key differences with this strategy. suffer from overcrowding, though Northern The first is that no part of the area it covers Rail’s anticipated service from December is the responsibility of either a Passenger 2008 will address that to a degree. It is Transport Executive or a regional body with important services on this route firstly cater public transport responsibilities. Secondly, for peak traffic at Sellafield and Barrow, with the challenge usually faced when producing services outside the peak being on as close a RUS, that of insufficient capacity to meet to an hourly pattern as possible. current or future demand, is not a major A number of consultation responses were problem here. As a result, this strategy received regarding a direct service between focuses on how to make the best use of Manchester and Burnley, including a report what is already available. -

Rail North West

Rail North West A Class 350 service sits in platform 3 at Oxenholme, perhaps saying how things could have been if the Windermere line had been electrified. Photo courtesy Lakes Line Rail Users Association/ Malcolm Conway Timetable Chaos Caused by Electrification Delay and Cancellation A week of cancellations and delays at meaning a large number of services the start of the new timetable on May needed re-planning to operate with 20th has led to calls by the Mayor of available units, though insufficient Manchester Andy Burnham and the drivers trained on units new to routes Mayor of the Liverpool City Region, (e.g. electric trains to Blackpool North) Steve Rotherham for Northern to be has added to the issue. stripped of its franchise if improvements weren’t made. The Lakes Line between Oxenholme and Windermere is feeling the effects of The disruption was caused primarily by the failure to electrify that line. The delays to the Manchester – Preston replacement bi-mode trains aren’t electrification, and cancellation of ready, but Northern has received some Oxenholme to Windermere schemes, Class 158 diesels from Scotland. With a Newsletter of the North West Branch1 of Railfuture — Summer 2018 Rail North West 2 Summer 2018 top speed of 90mph, they are easier to the greatest timetable change for a timetable on the West Coast Main Line generation as the government carries than the current Class 156 and 153 out the biggest modernisation of the rail units. However, the new units will entail network since Victorian times to an extensive driver training programme, improve services for passengers across and their lack of availability is causing the country.” significant cancellations on this line in particular. -

Scottish Railways: Sources

Scottish Railways: Sources How to use this list of sources This is a list of some of the collections that may provide a useful starting point when researching this subject. It gives the collection reference and a brief description of the kinds of records held in the collections. More detailed lists are available in the searchroom and from our online catalogue. Enquiries should be directed to the Duty Archivist, see contact details at the end of this source list. Beardmore & Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 100) GUAS Ref: UGD 100/1/17/1-2 Locomotive: GA diesel electric locomotive GUAS Ref: UGD 100/1/17/3 Outline and weight diagram diesel electric locomotive Dunbar, A G; Railway Trade Union Collection (GUAS Ref: UGD 47) 1949-67 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/1/6 Dumbarton & Balloch Joint Railway 1897-1909 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/1/3 Dunbar, A G, Railway Trade Union Collection 1869-1890 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/3 Dunbar, A G, Railway Trade Union Collection 1891-1892 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/2 London & North Eastern Railway 1922-49 Mowat, James; Collection (GUAS Ref: UGD 137) GUAS Ref: UGD 137/4/3/2 London & North Western Railway not dated Neilson Reid & Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 10) 1890 North British Locomotive Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 11) GUAS Ref: UGD 11/22/41 Correspondence and costs for L100 contract 1963 Pickering, R Y & Co Ltd (GUAS Ref: UGD 12) not dated Scottish Railway Collection, The (GUAS Ref: UGD 8) Scottish Railways GUAS Ref: UGD 8/10 Airdrie, Coatbridge & Wishaw Junction Railway 1866-67 GUAS Ref: UGD 8/39 Airdrie, Coatbridge & Wishaw Junction Railway 1867 GUAS Ref: UGD 8/40 Airdrie, Coatbridge