And Others TITLE Condom Availability in Schools: a Guide for Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View/Method……………………………………………………9

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

De Representatie Van Leraren En Onderwijs in Populaire Cultuur. Een Retorische Analyse Van South Park

Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Psychologie en Pedagogische Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2014-2015 De representatie van leraren en onderwijs in populaire cultuur. Een retorische analyse van South Park Jasper Leysen 01003196 Promotor: Dr. Kris Rutten Masterproef neergelegd tot het behalen van de graad van master in de Pedagogische Wetenschappen, afstudeerrichting Pedagogiek & Onderwijskunde Voorwoord Het voorwoord schrijven voelt als een echte verlossing aan, want dit is het teken dat mijn masterproef is afgewerkt. Anderhalf jaar heb ik op geregelde basis gezwoegd, gevloekt en getwijfeld, maar het overheersende gevoel is toch voldoening. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar veel tijd en moeite is ingekropen. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar ik toch wel fier op ben. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben dat ik zelfstandig op poten heb gezet en heb afgewerkt. Althans hoofdzakelijk zelfstandig, want ik kan er niet omheen dat ik regelmatig hulp heb gekregen van mensen uit mijn omgeving. Het is dan ook niet meer dan normaal dat ik ze hier even bedank. In de eerste plaats wil ik mijn promotor, dr. Kris Rutten, bedanken. Ik kon steeds bij hem terecht met vragen en opmerkingen en zijn feedback gaf me altijd nieuwe moed en inspiratie om aan mijn thesis verder te werken. Ik apprecieer vooral zijn snelle en efficiënte manier van handelen. Nooit heb ik lang moeten wachten op een antwoord, nooit heb ik vele uren zitten verdoen op zijn bureau. Bedankt! Ten tweede wil ik ook graag Ayna, Detlef, Diane, Katoo, Laure en Marijn bedanken voor deelname aan mijn focusgroep. Hun inzichten hebben ervoor gezorgd dat mijn analyses meer gefundeerd werden, hun enthousiasme heeft ertoe bijgedragen dat ik besefte dat mijn thesis zeker een bijdrage is voor het onderzoeksveld. -

Hiv/Aids Basics for Ngos and Family Planning Program Managers

THE CEDPA TRAINING MANUAL SERIES family planning plus: hiv/aids basics for ngos and family planning program managers Integrating Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS for NGOs, FBOs & CBOs Vol. I THE enable PROJECT ENABLING CHANGE FOR WOMEN'S THE CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND POPULATION ACTIVITIES Family Planning Plus: HIV/AIDS Basics for Non-Governmental Organizations and Family Planning Program Managers Integrating Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS for Non-Governmental Organizations, Faith-Based Organizations and Community-Based Organizations Volume I Family Planning Plus: HIV/AIDS Basics for NGOs and Family Planning Program Managers Authors Kathleen Callahan, MA Laurette Cucuzza, MPH This publication was supported by the United States Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement # HRN-A-00-98-00009-00. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Agency for International Development or The Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA). ii Family Planning Plus Abbreviations AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARV Antiretroviral CEDPA The Centre for Development and Population Activities HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus MTCT Mother-to-Child Transmission NGO Non-Governmental Organization PLWHA People Living with HIV/AIDS RH Reproductive Health STI Sexually Transmitted Infection WHO World Health Organization UNAIDS Joint United Nations Program on AIDS UNDP United Nations Development Programme USAID United States Agency for International Development VCT Voluntary Counseling and Testing Overview iii Acknowledgements Headquartered in Washington, DC, The Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA) is an international nonprofit organization that seeks to empower women at all levels of society to be full partners in development. -

Program Guide Report

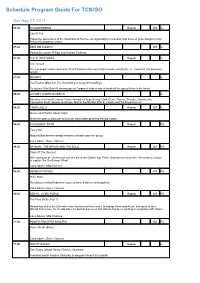

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Aug 21, 2011 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G City Of Fire Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:05 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G The Tycoon The fun begins when commoner Fred Flintstone discovers that he looks exactly like J.L. Gotrocks, the business tycoon. 07:30 SMURFS G The Fastest Wizard In The World/Sing A Song Of Smurflings To counter Wild Smurf's blazing speed Gargamel finds a way to break all the speed limits in the forest. 08:00 LOONEY TUNES CLASSICS G Adventures of iconic Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety, Silvester, Granny, the Tasmanian Devil, Speedy Gonzales, Marvin the Martian Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. 08:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G Beans and Pranks/ Movie Night Slinkman goes undercover to find out who's been pranking the big moose. 09:00 SYM-BIONIC TITAN Repeat PG Tashy 497 Modula finds another deadly beast to unleash upon the group. Cons.Advice: Some Violence 09:30 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Trials Of The Demon! After taking on the Scarecrow with the aid of the Golden Age Flash, Batman must travel to 19th century London to capture the Gentleman Ghost. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 GENERATOR REX WS PG Robo Bobo Rex discovers that Bobo has replaced himself with a robot duplicate. -

Program Guide Report

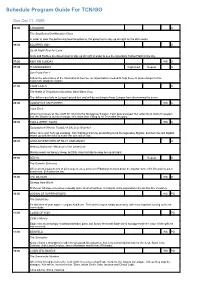

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Oct 11, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Sing Beans/Certifrycation Class In order to cook the performing food Sing Beans, the gang has to stay up all night as the dish cooks. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G Up All Night/ Pool For Love Andy and Rodney are determined to stay up all night in order to see the legendary Yellow Flash in the sky. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Sun Probe Part 1 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO G The Battle of Pimpleback Mountain/ Dead Bean Drop The Jellies rip a hole in Lumpus' prized tent and will do anything to keep Lumpus from discovering the secret. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G Cape Duck When Duck takes all the credit for catching the Shropshire Slasher, Tech gets annoyed. But when Duck starts to suspect that the Slasher is out for revenge, he's more than willing to let Tech take the glory. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G Sasquashed/ Xtreme Trouble/ A Life Less Guarded When Jerry and Tuffy go camping, Tom frightens them by pretending to be the legendary Bigfoot, but then the real Bigfoot teams up with the mice to scare the wits out of Tom. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY G Waking Nightmare / Because of the Undertoad Mandy needs her beauty sleep, but Billy risks his hide to keep her up all night. -

Relationship Between Knowledge of Proper Condom Use And

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN KNOWLEDGE OF PROPER CONDOM USE AND BEHAVIOUR AMONG STUDENTS OF KIRINYAGA UNIVERSITY BY MOLLY MUIGA A Research Proposal Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Award of Master’s degree in Psychology (Health Psychology) in the Department of Psychology of University of Nairobi 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University Signed: Date: NAME: MOLLY MUIGA Department of Psychology of University of Nairobi. Supervisors Declaration This research dissertation has been submitted for examination with my approval as university supervisor. Signed: Date: Name: Dr. CHARLES KIMAMO Senior Lecturer Department of Psychology University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION This research project is dedicated to my beloved daughter Prudence and Muiga family. Their forbearance of my inevitable absence from them while working on my project was a source of encouragement and determination for me to complete this document. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My gratitude goes to my superior Dr. Charles Kimamo for the specialized guidance, patience and many hours spent in supervising me throughout the project. I want to appreciate all staffs of the department of psychology, University of Nairobi for their support. I acknowledge the management of Kirinyaga University for their support during the data collection phase, staffs and students of Kirinyaga University for their support and participation respectively. I recognize my Family and colleagues for their endless inspiration and support during writing of the research project. I acknowledge the faithfulness of God throughout the research period. Lastly my gratitude goes to all those who participated in any way. -

Predicting Condom Use Behavior in Sexually Active Adolescents

PREDICTING CONDOM USE BEHAVIOR IN SEXUALLY ACTIVE ADOLESCENTS: APPLICATION OF THE HEALTH BELIEF MODEL AND DEVELOPMENTAL ASSETS FRAMEWORK by HOLLI M. SLATER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Holli M. Slater 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements My path to completing this PhD has been long, but rewarding. I am forever grateful to the many incredible people in my life who helped me along the way so that I was able to reach this incredible milestone. First and foremost, Diane Mitschke, my mentor, colleague, and friend. Thank you for gently nudging and eventually pushing me to finish. Your constant encouragement inspired me to never give up. It was because of you that I made it through this final push. Thank you to each of my committee members: Regina Praetorius, the first person to encourage me to pursue a PhD; Maria Scannapieco, the first person to encourage me to use this data; Larry Watson, for your support along the way; Sharon Homan, for talking through numerous ideas until we found something that would work; and finally, Mike Killian, who came on halfway through this process and spent endless hours answering question…after question…after question. There are a lot of words written here. I appreciate all of you for reading each and every one of them and providing me with valuable feedback. I am a stronger researcher because of all of you. -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park. -

HIV TRANSMISSION: Guidelines for Assessing Risk

HIV Transmission: Guidelines for Assessing Risk Now including hepatitis C transmission A RESOURCE FOR EDUCATORS, COUNSELLORS AND HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS Fifth Edition HIV Transmission: Guidelines for Assessing Risk A RESOURCE FOR EDUCATORS, COUNSELLORS AND HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS Fifth Edition Copyright © 2004 Canadian AIDS Society / Société canadienne du sida All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the publisher. Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction. ISBN Funding for this publication was provided by Health Canada. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors/researchers and do not necessarily reflect the official views of Health Canada. Ce document est aussi disponible en français. HIV TRANSMISSION: Guidelines for Assessing Risk Contents Foreward and Acknowledgements . 3 Fingering (Anal and Vaginal) . 25 Fisting (Anal and Vaginal) . 26 Quick Reference HIV . 5 Masturbation by Partner . 26 Quick Reference Hepatitis C . 6 Using Insertive Sex Toys . 27 Sadomasochistic Activities . 28 1. Guidelines Context Contact with Feces . 28 Urination . 28 Who is this document for? . 7 Vulva-to-vulva rubbing . 29 How the Document Was Produced . 7 Docking . 29 Affirming Sexuality and the Risk Reduction Breast milk . 29 Approach . 7 Cultural Practices . 29 The Challenge of Providing Accurate Information . 8 Part 2. Drug Use What Does Risk Mean? . 9 Injection Drug Use . 30 Assessing Risk of HCV Transmission . 10 Non-Injection Drug Use . 31 Risk Reduction . -

Why People Fail to Use Condoms for STD and HIV Prevention David T

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2009 Why People Fail to use Condoms for STD and HIV Prevention David T. Brunner Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Brunner, D. (2009). Why People Fail to use Condoms for STD and HIV Prevention (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/361 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY PEOPLE FAIL TO USE CONDOMS FOR STD AND HIV PREVENTION A Thesis Submitted To the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Masters of Social and Public Policy By David Brunner May 2009 WHY PEOPLE FAIL TO USE CONDOMS FOR STD AND HIV PREVENTION By David Brunner Approved January 26, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Moni McIntyre, Ph.D. Matthew Schneirov, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Associate Professor Graduate Center for Social and Public Sociology Department Policy (Committee Member) (Committee Chair) ________________________________ ________________________________ Ralph L. Pearson, Ph.D. Joseph Yenerall, Ph.D. Provost Duquesne University Director Graduate Center for Social and Public Policy Associate Professor of Sociology iii ABSTRACT WHY PEOPLE FAIL TO USE CONDOMS FOR STD AND HIV PREVENTION By David Brunner May 2009 Thesis supervised by professors Moni McIntyre, Ph.D. and Matthew Schneirov, Ph.D. The world is almost 30 years into the AIDS pandemic. -

The Biggest Myths About Stis

HUMAN RELATIONS MEDIA 8195 41 Kensico Drive Mount Kisco NY 10549 1-800-431-2050 Drive Kisco 41 Kensico Mount The Biggest Myths about STIs DVD Version ISBN-13: 978-1-55548-912-0 THE BIGGEST MYTHS ABOUT STIS Credits Executive Producer Anson W. Schloat Producer Peter Cochran Teacher’s Resource Book Karin Rhines Copyright 2013 Human Relations Media, Inc. © HUMAN RELATIONS MEDIA hrmvideo.com Biggest Myths about STIs http://www.hrmvideo.com THE BIGGEST MYTHS ABOUT STIS Table of Contents Teacher Resources DVD Menu i Introduction 1 Learning Objectives 2 Biographies of Featured Experts 3 Program Summary 4 NHES Performance Indicators (grades 6‐8) 5 NHES Performance Indicators (grades 9‐12) 7 Student Activities 1. Pre/Post Test 9 2. Dear Lucy 12 3. Myth Busting 13 4. What about STIs? 14 5. Help! 15 Student Fact Sheets 1. Condom Sense 16 2. What Is a Myth? 18 3. Teens and STIs 20 4. Diagnosis and Treatment 22 5. Resources 23 Other Programs from HRM 24 © HUMAN RELATIONS MEDIA hrmvideo.com Biggest Myths about STIs http://www.hrmvideo.com THE BIGGEST MYTHS ABOUT STIS DVD Menu Main Menu Play Chapter Selection From here, you can access many different paths of the DVD, beginning with the introduction and ending with the credits. 1. Introduction 2. “Trashy” People 3. A Person’s Appearance 4. Oral Sex 5. Sex with a Virgin 6. Lesbian Sex 7. Getting an STI Again 8. Checking Your Partner 9. The Pill 10. Sex in a Hot Tub 11. Multiple Condoms 12. Conclusion Teacher’s Resource Book A printable file of the accompanying Teacher’s Resource Book is available on the DVD.