Oroko Orthography Development: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Referred to As Class 18A (See Hyman 1980:187)

WS1 Remarks on the nasal classes in Mungbam and Naki Mungbam and Naki are two non-Grassfields Bantoid languages spoken along the northwest frontier of the Grassfields area to the north of the Ring languages. Until recently, they were poorly described, but new data reveals them to show significant nasal noun class patterns, some of which do not appear to have been previously noted for Bantoid. The key patterns are: 1. Like many other languages of their region (see Good et al. 2011), they make productive use of a mysterious diminutive plural prefix with a form like mu-, with associated concords in m, here referred to as Class 18a (see Hyman 1980:187). 2. The five dialects of Mungbam show a level of variation in their nasal classes that one might normally expect of distinct languages. a. Two dialects show no evidence for nasals in Class 6. Two other dialects, Munken and Ngun, show a Class 6 prefix on nouns of form a- but nasal concords. In Munken Class 6, this nasal is n, clearly distinct from an m associated with 6a; in Ngun, both 6 and 6a are associated with m concords. The Abar dialect shows a different pattern, with Class 6 nasal concords in m and nasal prefixes on some Class 6 nouns. b. The Abar, Biya, and Ngun dialects show a Class 18a prefix with form mN-, rather than the more regionally common mu-. This reduction is presumably connected to perseveratory nasalization attested throughout the languages of the region with a diachronic pathway along the lines of mu- > mũ- > mN- perhaps providing a partial example for the development of Bantu Class 9/10. -

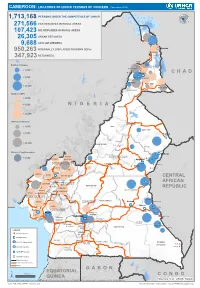

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Climate Change Adaptation Among Forest-Dependent Communities in Bamboko Forest Reserve, the Southwest Region of Cameroon

Non-timber forest products and climate change adaptation among forest-dependent communities in Bamboko forest reserve, the southwest region of Cameroon Tieminie Robinson Nghogekeh ( [email protected] ) TTRECED Cameroon Chia Eugene Loh GIZ Yaounde,Cameroon Tieguhong Julius Chupezi African Development Bank Nghobuoche Frankline Mayiadieh Universite de Yaounde I Piabuo Serge Mandiefe ICRAF-Cameroon Mamboh Rolland Tieguhong Universite de Yaounde II Research Keywords: NTFPs, Climate change, adaptation, BFR, South West Region, Cameroon Posted Date: November 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-61744/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on March 9th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-020-00215-z. Page 1/24 Abstract Background: Forests are naturally endowed to combat climate change by protecting people and livelihoods as well as creating a base for sustainable economic and social development. But this natural mechanism is often hampered by anthropogenic activities. It is therefore imperative to take measures that are environmentally sustainable not only for mitigation but also for its adaptation. This study was carried out to assess the role of Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) as a strategy to cope with the impacts of climate change among forest-dependent communities around the Bamkoko Forest Reserve in the South West Region of Cameroon. Methods: Datasets were collected through household questionnaires (20% of the population in each village that constitute the study site was a sample), participatory rural appraisal techniques, transect walks in the 4 corners of the Bamboko Forest Reserve with a square sample of 25 m2 x 25 m2 to identied and record NTFPs in the reserve, and direct eld observations. -

Rapid Protection Assessments Summary Report

Rapid Protection Assessments Summary Report Danish Refugee Council Southwest Cameroon December 2020 Cameroon – RPA Report – December 2020 Table of Content 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Information on Key Informants (KIs) ............................................................................................ 5 2. Communities’ General Profile ..................................................................................... 6 2.1 Pre and post crisis population movements ................................................................................. 6 2.2 Vulnerability profile ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Displacement profile ................................................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 Vulnerability types .................................................................................................................... 7 3. Access to services ...................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Education ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Health ........................................................................................................................................... -

Bernander Et Al AAM NEC in Bantu

The negative existential cycle in Bantu1 Bernander, Rasmus, Maud Devos and Hannah Gibson Abstract Renewal of negation has received ample study in Bantu languages. Still, the relevant literature does not mention a cross-linguistically recurrent source of standard negation, i.e., the existential negator. The present paper aims to find out whether this gap in the literature is indicative of the absence of the Negative Existential Cycle (NEC) in Bantu languages. It presents a first account of the expression of negative existence in a geographically diverse sample of 93 Bantu languages. Bantu negative existential constructions are shown to display a high degree of formal variation both within dedicated and non-dedicated constructions. Although such variation is indicative of change, existential negators do not tend to induce changes at the same level as standard negation. The only clear cases of the spread of an existential negator to the domain of standard negation in this study appear to be prompted by sustained language contact. Keywords: Bantu languages, negation, language change, morphology 1 Introduction The Bantu language family comprises some 350-500 languages spoken across much of Central, Eastern and Southern Africa. According to Grollemund et al. (2015), these languages originate from a proto-variety of Bantu, estimated to have been spoken roughly 5000 years ago in the eastern parts of present-day northwest Cameroon. Many Bantu languages exhibit a dominant SVO word order. They are primarily head-marking, have a highly agglutinative morphology and a rich verbal complex in which inflectional and derivational affixes join to an obligatory verb stem. The Bantu languages are also characterised by a system of noun classes – a form of grammatical gender. -

November 2011 EPIGRAPH

République du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon Paix-travail-patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Ministry of Employment and Formation Professionnelle Vocational Training INSTITUT DE TRADUCTION INSTITUTE OF TRANSLATION ET D’INTERPRETATION AND INTERPRETATION (ISTI) AN APPRAISAL OF THE ENGLISH VERSION OF « FEMMES D’IMPACT : LES 50 DES CINQUANTENAIRES » : A LEXICO-SEMANTIC ANALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of a Vocational Certificate in Translation Studies Submitted by AYAMBA AGBOR CLEMENTINE B. A. (Hons) English and French University of Buea SUPERVISOR: Dr UBANAKO VALENTINE Lecturer University of Yaounde I November 2011 EPIGRAPH « Les écrivains produisent une littérature nationale mais les traducteurs rendent la littérature universelle. » (Jose Saramago) i DEDICATION To all my loved ones ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Immense thanks goes to my supervisor, Dr Ubanako, who took out time from his very busy schedule to read through this work, propose salient guiding points and also left his personal library open to me. I am also indebted to my lecturers and classmates at ISTI who have been warm and friendly during this two-year programme, which is one of the reasons I felt at home at the institution. I am grateful to IRONDEL for granting me the interview during which I obtained all necessary information concerning their document and for letting me have the book at a very moderate price. Some mistakes in this work may not have been corrected without the help of Mr. Ngeh Deris whose proofreading aided the researcher in rectifying some errors. I also thank my parents, Mr. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Replacive Grammatical Tone in the Dogon Languages

University of California Los Angeles Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 c Copyright by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 Abstract of the Dissertation Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages by Laura Elizabeth McPherson Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Russell Schuh, Co-chair Professor Bruce Hayes, Co-chair This dissertation focuses on replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages of Mali, where a word’s lexical tone is replaced with a tonal overlay in specific morphosyntactic contexts. Unlike more typologically common systems of replacive tone, where overlays are triggered by morphemes or morphological features and are confined to a single word, Dogon overlays in the DP may span multiple words and are triggered by other words in the phrase. DP elements are divided into two categories: controllers (those elements that trigger tonal overlays) and non-controllers (those elements that impose no tonal demands on surrounding words). I show that controller status and the phonological content of the associated tonal overlay is dependent on syntactic category. Further, I show that a controller can only impose its overlay on words that it c-commands, or itself. I argue that the sensitivity to specific details of syntactic category and structure indicate that Dogon replacive tone is not synchronically a phonological system, though its origins almost certainly lie in regular phrasal phonology. Drawing on inspiration from Construction Morphology, I develop a morphological framework in which morphology is defined as the id- iosyncratic mapping of phonological, syntactic, and semantic information, explicitly learned by speakers in the form of a construction. -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Neural Machine Translation for Extremely Low-Resource African Languages: a Case Study on Bambara

Neural Machine Translation for Extremely Low-Resource African Languages: A Case Study on Bambara Allahsera Auguste Tapo1;∗, Bakary Coulibaly2, Sébastien Diarra2, Christopher Homan1, Julia Kreutzer3, Sarah Luger4, Arthur Nagashima1, Marcos Zampieri1, Michael Leventhal2 1Rochester Institute of Technology 2Centre National Collaboratif de l’Education en Robotique et en Intelligence Artificielle (RobotsMali) 3Google Research, 4Orange Silicon Valley ∗[email protected] Abstract population have access to “encyclopedic knowl- edge” in their primary language, according to a Low-resource languages present unique chal- 2014 study by Facebook.2 MT technologies could lenges to (neural) machine translation. We dis- help bridge this gap, and there is enormous interest cuss the case of Bambara, a Mande language in such applications, ironically enough, from speak- for which training data is scarce and requires ers of the languages on which MT has thus far had significant amounts of pre-processing. More than the linguistic situation of Bambara itself, the least success. There is also great potential for the socio-cultural context within which Bam- humanitarian response applications (Öktem et al., bara speakers live poses challenges for auto- 2020). mated processing of this language. In this pa- Fueled by data, advances in hardware technol- per, we present the first parallel data set for ogy, and deep neural models, machine translation machine translation of Bambara into and from (NMT) has advanced rapidly over the last ten years. English and French and the first benchmark re- Researchers are beginning to investigate the ef- sults on machine translation to and from Bam- bara. We discuss challenges in working with fectiveness of (NMT) low-resource languages, as low-resource languages and propose strategies in recent WMT 2019 and WMT 2020 tasks (Bar- to cope with data scarcity in low-resource ma- rault et al., 2019), and in underresourced African chine translation (MT). -

Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Maize Production in the West Region of Cameroon for Sustainable Development

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.4, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania EVALUATING THE CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF MAIZE PRODUCTION IN THE WEST REGION OF CAMEROON FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Godwin Anjeinu Abu1, Raoul Fani Djomo-Choumbou1 and Stephen Adogwu Okpachu2 1. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Agriculture PMB 2373, Makurdi Benue State- Nigeria 2. Federal College of Education (Technical), Potiskum, Yobe State, Nigeria ABSTRACT A study of Evaluating the constraints and opportunities of Maize production in the West Region of Cameroon was carried out using primary and secondary data collected. One hundred and twenty (120) maize farmers randomly selected from eight (8) villages were interviewed using structured questionnaire. Data from the study were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentages, and inferential statistics such as multiple linear regressions. The study found that most maize farmers in the study area were small scale farmers and are full time farmers, the major maize production constraints was poor access to credit facilities. it was also found any unit increase in the quantity of any of the resources used for maize production will increase maize output by the value of their estimated coefficients respectively , however to raise maize production, the study recommend that financial institutions such as agricultural and community banks should be established in the study area with the simple procedure of securing loans. The relevant government agencies and non- governmental organization should mobilize the maize farmers to form themselves into formidable group so that they can derive maximum benefit of collective union.