Hung Liu, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Life and Death Images of Exceptional Women and Chinese Modernity Wei Hu University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Beyond Life And Death Images Of Exceptional Women And Chinese Modernity Wei Hu University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hu, W.(2017). Beyond Life And Death Images Of Exceptional Women And Chinese Modernity. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4370 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND LIFE AND DEATH IMAGES OF EXCEPTIONAL WOMEN AND CHINESE MODERNITY by Wei Hu Bachelor of Arts Beijing Language and Culture University, 2002 Master of Laws Beijing Language and Culture University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Michael Gibbs Hill, Major Professor Alexander Jamieson Beecroft, Committee Member Krista Jane Van Fleit, Committee Member Amanda S. Wangwright, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Wei Hu, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To My parents, Hu Quanlin and Liu Meilian iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During my graduate studies at the University of South Carolina and the preparation of my dissertation, I have received enormous help from many people. The list below is far from being complete. First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my academic advisor, Dr. -

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

POWER an D IDENTITY I N the CHINES E WORLD ORDE R Festschrift M Honour of Professor Wang Gomgwui

POWER AN D IDENTITY I N THE CHINES E WORLD ORDE R Festschrift m Honour of Professor Wang Gomgwui Edited by Billy K.L. So John Fitzgerald Huang Jianli James K. Chin # » * # i h Bf c *t HONG KON G UNIVERSIT Y PRES S Hong Kon g Universit y Pres s 14/F Hing Wai Centr e 7 Tin Wan Pray a Roa d Aberdeen Hong Kon g © Hon g Kong Universit y Pres s 200 3 ISBN 96 2 20 9 59 0 9 All rights reserved . No portio n o f this publication ma y be reproduced o r transmitte d i n an y form o r by an y means, electronic o r mechanical , includin g photocopy, recording , or an y information storag e o r retrieva l system , withou t prior permissio n i n writing fro m th e publisher . This volume i s published with th e suppor t o f the Universit y o f Hong Kon g an d the Australia n Academ y o f the Humanities . British Librar y Cataloguing-in-Publicatio n Dat a A catalogu e recor d fo r thi s book i s available fro m th e British Library . Secure On-lin e Orderin g http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Liang Yu Printing Factory Ltd., Hong Kong, China . Contents Acknowledgements i x Contributors x i Introduction 1 Billy K. L . So Prologue Wang Gungwu : Th e Historia n i n Hi s Times 1 1 Philip A. Kuhn Part I . I n Searc h o f Power : Powe r Restructurin g i n 3 3 Modern Chin a 1. -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

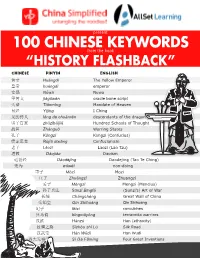

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Melissa Barber – the Cicada and the Plum September 22 – October 9 2016

The Corner Store Gallery www.cornerstoregallery.com Melissa Barber – The Cicada and the Plum September 22 – October 9 2016 This exhibition introduces work from Melissa’s new series The Cicada and the Plum. This series concerns itself with the exploration of the transition of a four thousand year old culture into the modern day era, namely that of China. Melissa has been strongly influenced by antique photographs of Chinese society that reveal a culture steeped in tradition but on the very verge of change. Melissa Barber is a self-taught artist based in the Central West town of Canowindra. She has been painting professionally since the age of 24, exhibiting from time to time in Sydney and Melbourne, and has paintings in private and corporate collections within Australia and internationally. GST included in all prices. 1 The Divorcee (The Cicada and the Plum Series), oil on canvas, 91.5cm x 91.5cm. $5500 Wenxiu was the second wife of Puyi. She was actually his first choice before his advisers told him to marry Wanrong. She was 14 when they married and she became extremely bored and lonely with palace life as Puyi mainly ignored her. She eventually escaped and with the help of a friend managed to arrange a divorce from Puyi - the first ever royal divorce in Chinese Imperial history. It is said that she ended up becoming a school teacher and remarrying. The orchids in her hair are symbolic of the Chinese meaning for love and marriage, and the fact that they’re white refers to death and ghostliness adding another meaning to her marriage to Puyi. -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 1-2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Manling Luo _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Politics of Place-Making _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Politics of Place-Making T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 43-75 www.brill.com/tpao 43 The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang Manling Luo Indiana University The Luoyang qielan ji 洛陽伽藍記 (Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang; hereafter Records), compiled by Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (fl. 547) in roughly 547 CE, commemorates the ruined capital city of the North- ern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534).1 One of the few major works to survive from the period, the Records has received much critical attention, with topics ranging from its textual history to its historical and literary value. This essay focuses on what I call the “politics of place-making” in the memoir, that is, engagements with Luoyang’s space as expressions of power before and after the city’s abandonment, as represented and un- derstood by Yang. These ignored aspects shed light on the central con- cerns that motivated his writing, thereby revealing his perspective on the intersections of place, power, and human agency. The analysis al- lows us to better understand his innovations in pioneering an unofficial, space-centered historiography that defines historical agents as place- makers whose deeds and lives are anchored spatially as much as tempo- rally. -

Empresses, Bhikṣuṇῑs, and Women of Pure Faith

EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH: BUDDHISM AND THE POLITICS OF PATRONAGE IN THE NORTHERN WEI By STEPHANIE LYNN BALKWILL, B.A. (High Honours), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, July 2015 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Empresses, Bhikṣuṇīs, and Women of Pure Faith: Buddhism and the Politics of Patronage in the Northern Wei AUTHOR: Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, B.A. (High Honours) (University of Regina), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 410. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the contributions that women made to the early development of Chinese Buddhism during the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏 (386–534 CE). Working with the premise that Buddhism was patronized as a necessary, secondary arm of government during the Northern Wei, the argument put forth in this dissertation is that women were uniquely situated to play central roles in the development, expansion, and policing of this particular form of state-sponsored Buddhism due to their already high status as a religious elite in Northern Wei society. Furthermore, in acting as representatives and arbiters of this state-sponsored Buddhism, women of the Northern Wei not only significantly contributed to the spread of Buddhism throughout East Asia, but also, in so doing, they themselves gained increased social mobility and enhanced social status through their affiliation with the new, foreign, and wildly popular Buddhist tradition. -

Cixi Draktronens Härskarinna

Lunds Universitet KINK11 VT 2010 Språk- och Litteraturcentrum Handledare Michael Schoenhals Kandidatkurs, Kinesiska Cixi Draktronens Härskarinna Charlotte Colliander Sammanfattning Änkekejsarinnan Cixi styrde Kina under kejsardömets sista halvsekel. Hon utmålades länge som maktgalen och grym, men på senare tid har en mer nyanserad bild presenterats. I den här uppsatsen analyseras hur ett antal händelser i Cixis liv i relation till Guangxu-kejsaren och hans konkubin Zhenfei har beskrivits i olika källor. Syftet är att se vad dessa händelser säger om Cixi som person och om det är möjligt att få en klar och sann bild av henne. Namn och nyckelord Cixi, Yehenala, Xianfeng, Tongzhi, Prins Gong, Prins Chun, Guangxu, Zhenfei, Qingdynastin, änkekejsarinna, De hundra dagarnas reform, förmyndarregent. Abstract Empress Dowager Cixi governed China during the final five decades of the Qing dynasty. She was for many years depicted as a cruel megalomaniac, lately Cixi has been described in a more nuanced way. This paper seeks to analyze how a selection of sources describe a number of specific events in connection with Cixi and the Guangxu-emperor and his concubine Zhenfei. The objective is to discuss what this reveals about Cixi as an individual and evaluate whether it is possible for historians to arrive at a more truthful picture. Names and Keywords Cixi, Yehenala, Xianfeng, Tongzhi, Prins Gong, Guangxu, Zhenfei, Qingdynasy, Empress Dowager, The Hundred Daysʼ Reform, regency. 摘要: 在清朝的最后五十年慈禧太后统 治中国。多年以来,她被描述为 一个残忍并狂妄自 大的人, 但近来对 慈禧的描述却有些不同。这 篇文章解析了这 些资 料是怎样 描述 发 生在慈禧,光绪 皇帝及珍妃之间 的具体事件的。本文的目的是探讨这 些资 料所展 现 出的慈禧是怎样 的一个人,这 或许 会让 人们认识 到一个更为 真实 的慈禧。 关键词 : 慈禧,叶赫那拉,咸丰,同治, 恭忠亲 王,光绪 ,珍妃,清朝,皇太后,戊戌变 法, 摄 政权。 2 Änkekejsarinnan Cixi i Beijing år 1904 http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/97/46297-004-7878BDA4.jpg 3 Innehållsförtecking 1.