Tocc0264notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

Toccata Classics Cds Are Also Available in the Shops and Can Be Ordered from Our Distributors Around the World, a List of Whom Can Be Found At

Recorded in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire on 25–27 June 2013 Recording engineers: Maria Soboleva (Piano Concerto) and Pavel Lavrenenkov (Cello Concerto) Booklet essays by Anastasia Belina and Malcolm MacDonald Design and layout: Paul Brooks, [email protected] Executive producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0219 © 2014, Toccata Classics, London P 2014, Toccata Classics, London Come and explore unknown music with us by joining the Toccata Discovery Club. Membership brings you two free CDs, big discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings and Toccata Press books, early ordering on all Toccata releases and a host of other benefits, for a modest annual fee of £20. You start saving as soon as you join. You can sign up online at the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com. Toccata Classics CDs are also available in the shops and can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 E-mail: [email protected] A student of Ferdinand Leitner in Salzburg and Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa at Tanglewood, Hobart Earle studied conducting at the Academy of Music in Vienna; received a performer’s diploma in IGOR RAYKHELSON: clarinet from Trinity College of Music, London; and is a magna cum laude graduate of Princeton University, where he studied composition with Milton Babbitt, Edward Cone, Paul Lansky and Claudio Spies. In 2007 ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME THREE he was awarded the title of Honorary Professor of the Academy of Music in Odessa. -

Tezfiatipnal "

tezfiatipnal" THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Borodin Quartet MIKHAIL KOPELMAN, Violinist DMITRI SHEBALIN, Violist ANDREI ABRAMENKOV, Violinist VALENTIN BERLINSKY, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 25, 1990, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 .............................. PROKOFIEV Allegro sostenuto Adagio, poco piu animate, tempo 1 Allegro, andante molto, tempo 1 Quartet No. 3 (1984) .......................................... SCHNITTKE Andante Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, with Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 ...... BEETHOVEN Adagio, ma non troppo; allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alia danza tedesca: allegro assai Cavatina: adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge The Borodin Quartet is represented exclusively in North America by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, Inc., San Francisco. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twenty-eighth Concert of the lllth Season Twenty-seventh Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 ........................ SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev, born in Sontsovka, in the Ekaterinoslav district of the Ukraine, began piano lessons at age three with his mother, who also encouraged him to compose. It soon became clear that the child was musically precocious, writing his first piano piece at age five and playing the easier Beethoven sonatas at age nine. He continued training in Moscow, studying piano with Reinhold Gliere, and in 1904, entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Anatoly Lyadov, orchestration with Rimsky- Korsakov, and conducting with Alexander Tcherepnin. -

A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential Actf Ors in Performer Repertoire Choices

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 2020 A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices Yuan-Hung Lin Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lin, Yuan-Hung, "A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices" (2020). Dissertations. 1799. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1799 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF SELECT WORLD-FEDERATED INTERNATIONAL PIANO COMPETITIONS: INFLUENTIAL FACTORS IN PERFORMER REPERTOIRE CHOICES by Yuan-Hung Lin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Elizabeth Moak, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen Elder Dr. Michael Bunchman Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe August 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Yuan-Hung Lin 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT In the last ninety years, international music competitions have increased steadily. According to the 2011 Yearbook of the World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC)—founded in 1957—there were only thirteen world-federated international competitions at its founding, with at least nine competitions featuring or including piano. One of the founding competitions, the Chopin competition held in Warsaw, dates back to 1927. -

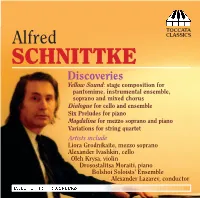

Toccata Classics TOCC 0091 Notes

TOCCATA Alfred CLASSICS SCHNITTKE Discoveries Yellow Sound: stage composition for pantomime, instrumental ensemble, soprano and mixed chorus Dialogue for cello and ensemble Six Preludes for piano Magdalina for mezzo soprano and piano Variations for string quartet Artists include Liora Grodnikaite, mezzo soprano Alexander Ivashkin, cello Oleh Krysa, violin Drosostalitsa Moraiti, piano Bolshoi Soloists’ Ensemble Alexander Lazarev, conductor SCHNITTKE DISCOVERIES by Alexander Ivashkin This CD presents a series of ive works from across Alfred Schnittke’s career – all of them unknown to the wider listening public but nonetheless giving a conspectus of the evolution of his style. Some of the recordings from which this programme has been built were unreleased, others made specially for this CD. Most of the works were performed and recorded from photocopies of the manuscripts held in Schnittke’s family archive in Moscow and in Hamburg and at the Alfred Schnittke Archive in Goldsmiths, University of London. Piano Preludes (1953–54) The Piano Preludes were written during Schnittke’s years at the Moscow Conservatory, 1953–54; before then he had studied piano at the Moscow Music College from 1949 to 1953. An advanced player, he most enjoyed Rachmaninov and Scriabin, although he also learned and played some of Chopin’s Etudes as well as Rachmaninov’s Second and the Grieg Piano Concerto. It was at that time that LPs irst became available in the Soviet Union, and so he was able to listen to recordings of Wagner’s operas and Scriabin’s orchestral music. The piano style in the Preludes is sometimes very orchestral, relecting his interest in the music of these composers. -

Eliso Virsaladze Элисо Вирсаладзе

ელისო ვირსალაძე Eliso Virsaladze Элисо Вирсаладзе Eliso VirsaladzE Элисо Вирсаладзе თბილისი Tbilisi Тбилиси 2012 შემდგენელი და რედაქტორი Edited and compiled by Редактор и составитель მანანა ახმეტელი Manana Akhmeteli Манана Ахметели დიზაინერი Design: Дизайнер ბესიკ დანელია Besik Danelia Бесик Данелия თარგმანი ქართულ ენაზე: Georgian translation: Перевод на Грузинский язык: მანანა ახმეტელი Manana Akhmeteli Манана Ахметели თარგმანი ინგლისურ ენაზე: ნინო ახვლედიანი, თამუნა ლოლუა, English translation: Перевод на Английский язык: მიხეილ გელაშვილი Nino Akhvlediani, Tamuna Lolua, Нино Ахвледиани, Тамуна Лолуа, Mikheil Gelashvili Михаил Гелашвили თარგმანი რუსულ ენაზე: მანანა ახმეტელი, ნინო ახვლედიანი, Russian translation: Перевод на Русский язык: ლალი ხუჭუა Manana Akhmeteli, Nino Akhvlediani, Манана Ахметели, Нино Ахвледиани, Lali Khuchua Лали Хучуа განსაკუთრებული მადლობა: ქერენ ჩეპმენ კლარკს, Special thanks: Особая благадарность: მიხეილ გელაშვილს Caryne Chapman Clark, Mikheil Gelashvili Керен Чепмен Кларк, Михаилу Гелашвили ქართული ტექსტის კომპიტერული უზრუნველყოფა: Photographs: В книге использованы фотографии ვერა ფცქიალაძე Derek Prager, Yuri Mechitov, Дерека Пражера, Юрия Мечитова, Gia Gogatishvili, Alexander Saakov, Гии Гогатишвили, Александра Саакова, წიგნში გამოყენებულია დერეკ პრაჟერის, Irakli Zviadadze and Virsaladze family Ираклия Звиададзе и из семейного იური მეჩითოვის, გია გოგატიშვილის, archive архива Элисо Вирсаладзе ალექსანდრე სააკოვის, ირაკლი ზვიადაძის ფოტოები და აგრეთვე მასალა ელისო ვირსალაძის საოჯახო ფოტოარქივიდან პროექტის მენეჯერი -

Nikoloz Rachveli the Rest Is Silence Requiem for Holocaust and Violence Victims for Mezzo-Soprano, Mixed Choir and Orchestra *40 Min

Nikoloz Rachveli The Rest is Silence Requiem for Holocaust and violence victims for mezzo-soprano, mixed choir and orchestra *40 min World premiere - 19.12 2016 at the Teatro alla Scala Georgian Premiere - 27.12.2017 at the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre This composition, which was specially created for Anita Rachvelishvili's concert at the Teatro alla Scala, is dedicated to the memory of people who have been tortured and killed unjustly. The final words from Shakespeare's Hamlet are used for a title. The work is based on a poem "Death Fugue”, written by an outstanding poet Paul Celan (1920-1970) about his experience in the Nazi concentration camps. Five-piece vocal cycle consists of Georgian poet Vazha Pshavela’s (1861-1915) poem “I could not save anyone” and poem about Jewish boy - 1st part, 2nd part - The Fest of the Tortured Souls, 3rd - Hebrew lullaby by Emanuel Harussi (1903- 1979), 4th - "Death Fugue" by Paul Celan, and 5th part - Postludium, where Paul Celan reads his own poem written in the concentration camp. After the premiere on December 27, 2017 the mesmerized public was silent for a long time before a standing ovation. "Although defending human rights is the supreme value of humanity, injustice and brutality remains an irreparable problem of nowadays. If we consider the Earth as a whole, we find that the largest percentage of its population is still sacrificed to dictatorship, repression, the death penalty, political and religious confrontations, terrorist acts and territorial conflicts. Mental and technological progress has failed to protect the most vulnerable people until today; the world is still full of displaced refugees, innocent prisoners fighting for the freedom of speech. -

23&24Apr HP Fullset AW V9

%HUH]RYVN\fࣜ˿ʩਥ Berezovsky plays Tchaikovsky ᘣ݇শ ຝ͌ ۂ СԓΛʩ ᚓಙcАܞ Perry So ۂconductor ࣜ˿ʩਥ ࠌ%ɩሁȹ፡ೄԾۗςcА ᗲϤɺʪ҄ؿ҄ Ķ τ၀ुؿ҄ Ķ Αనࡈ܈ሔኴؿɩϷ Ķ ร ॗʩਥ ᆅईؿּ҄ˈ ፡ೄ Boris Berezovsky xɻͤࢠx piano ۂࣳᖓࡐഥʩ ࠌ%ɣሁʄ͚ᚊςcА Ϸ τɈؿ҄ ྺ ጹ⸈ؿ҄ Programme LIADOV The Enchanted Lake, Op. 62 ࠗಋཋ̎ႇАɁࡗ TCHAIKOVSKY Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, RTHK Production Team Op. 23 ཋ̎ႇА Radio Production Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso – ፣ࠑဟႇ Audio Producer ະ Calvin Lai Allegro con spiritoۺፆ Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo 1 ཋ̎ຝ͌˚ܛ Presenters ңཽޔ Jenny Lee Allegro con fuoco ధᓤ Ben Pelletier үᐲᅌဟႇ Simulcast Producer – Intermission – ᒉɥႚ Raymond Chung үᐲᅌ˚ܛ Simulcast Presenter PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 5 in B flat, Op. 100 ңཽޔ Jenny Lee Andante Allegro marcato ཋ഼ႇА TV Production Adagio ဟႇ Executive Producer ใᏬജ Henry Wan Allegro giocoso ᇁኒ Producer Edde Lam ڲۺ׳ Хଉᇁኒ Assistant Producer כᅌcԎقͰႠ ଊ )0 Tang Chun-cheong ˂ˀؿࠑᅥผࠗͅಋཋ̎፣ࠑʥ፣ᄧcࠗಋཋ̎̒̎ ןሳࢯ क̎dࠗಋཋ̎̒̎ʥࠗಋཋ̎၉ɐᄤᅌॎעܱ౨ʒ Ɏʟࣂʗͅಲ㡊ཋ഼ ˀ˂ ᅥᖪᚋਐ Music Score Advisor ZZZUWKNRUJKN үᅌˮe The 23 Apr concert is recorded by RTHK and is broadcast live on RTHK Radio 4 (FM Stereo 97.6 – 98.9 MHz). ޔޔ Tina Ma The audio/visual recording will be simulcast via TVB Pearl, on RTHK Radio 4 and RTHK’s website (www.rthk.org.hk) on 12 Jun (Sat) at 2:35pm. ྡྷΔ፣ᄧᘐ Mobile Production Unit ሳᙬ Jolly Tang ΈϽᜮଠ cᇼᗐઌʹొཋʥԯˢᚊባສeʑɺඝࠕdᙘᄧd፣ࠑֶ፣ᄧeूɣࡼτکሌᅥ ཋ̎ʥཋ഼ႇАɮೡ ȹ҄ؿࠑᅥe Radio and TV Outdoor Broadcast Engineering Dear patrons ཋޔޫᄤᅌɮೡ For a wonderful concert experience, kindly switch off your mobile phone and other beeping devices PCCW Broadcasting Section before the concert begins. -

Lydia Chernicoff, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2019

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PARADOX AND PARALLEL: ALFRED SCHNITTKE’S WORKS FOR VIOLIN IN CONTEXT Lydia Chernicoff, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2019 Dissertation Directed By: Professor JaMes Stern, School of Music In his works for violin, Alfred Schnittke explores and challenges the traditional boundaries of Western composition. This dissertation project is founded on the conviction that these works by Schnittke, despite their experiMental and idiosyncratic nature, hold an integral place in the standard violin repertoire as well as in the broader canon of Western classical music. The argument will be supported by three recital prograMs that place the works in the context of that canon and an investigation of how Schnittke’s compositional language relates to that of the western European composers, revealing his complex and distinctive voice. By tracking his deconstruction and reworking of the music of other composers, we see Schnittke’s particular formality and musical rhetoric, as well as his energetic and artistic drive, and we see that his works are not merely experiMental—they renew the forms whose boundaries they transgress, and they exhibit a gravity, a tiMelessness, and a profound humanity, earning the composer his rightful place in the lineage of Western classical music. The first and third recitals were performed in Ulrich Recital Hall, and the second recital was performed in Gildenhorn Recital Hall, all at the University of Maryland. Recordings of all three recitals can be accessed at the University of Maryland Hornbake Library. PARADOX AND PARALLEL: ALFRED SCHNITTKE’S WORKS FOR VIOLIN IN CONTEXT By Lydia Chernicoff Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillMent of the requireMents for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2019 Advisory ComMittee: Professor JaMes Stern, Chair Professor Olga Haldey Professor Irina Muresanu Professor Rita Sloan Professor Eric ZakiM © Copyright by Lydia Chernicoff 2019 To every artist in search of his or her voice. -

Narrativity in Postmodern Music: a Study of Selected Works of Alfred Schnittke

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-31-2012 12:00 AM Narrativity in Postmodern Music: A Study of Selected Works of Alfred Schnittke Karen K. Ching The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Catherine Nolan The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Karen K. Ching 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Ching, Karen K., "Narrativity in Postmodern Music: A Study of Selected Works of Alfred Schnittke" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 910. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/910 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Narrativity in Postmodern Music: A Study of Selected Works of Alfred Schnittke (Spine title: Narrativity in Postmodern Music) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Karen K. Ching Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Karen K. Ching 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Catherine Nolan Dr. Thomas Carmichael ______________________________ Dr. John Doerksen Supervisory Committee ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Peter Franck Dr. Richard Parks ______________________________ Dr. -

The V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire International

The V. Sarajishvili #1 Tbilisi State Conservatoire International 3 Manana Doijashvili - Greeting 3 Rusudan Tsurtsumia – Introduction Research 7 The V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire Center for 8 Manana Andriadze - The Tbilisi State Conservatoire’s Georgian Folk Music Traditional Department 10 Program of Scientific Works at the Second International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony Polyphony 11 First English Translation of Essays on Georgian Folk Music BULLETIN 13 Musical Scores 99 Georgian Songs 14 Georgian Traditional Music in 2004 16 Field Expeditions Ethnomusicological Field Expedition in Dmanisi 17 Ethnomusicological Field Expedition in Ozurgeti Region, Guria 18 Ethnomusicological Field Expedition in Lentekhi (Lower Svaneti) and Tsageri (Lechkhumi) 20 Ethnomusicological Field Expedition in Telatgori (Kartli) 21 Georgian Ethnomusciologists Evsevi (Kukuri) Chokhonelidze 23 Georgian Folk Groups The Anchiskhati Church Choir and Folk Group Dzveli Kiloebi 25 Georgian Songmasters “Each Time I Sing It Differently” - An Interview with Otar Berdzenishvili 28 Georgian Folk Song – New Transcription TBILISI. DECEMBER. 2004 Kiziq Boloze 2 This bulletin is published bi-annually in Georgian and English through the support of UNESCO ' International Research Center The for Traditional Polyphony of Tbilisi V. Sarajishvili State Conservatoire, 2004. ISSN 1512 - 2883 Editors: Rusudan Tsurtsumia, Tamaz Gabisonia Translators: Maia Kachkachishvili, Carl Linich Design: Nika Sebiskveradze, George Kokilashvili Computer services: Kakha Maisuradze Printed by: Polygraph 3 Prof. MANANA DOIJASHVILI Prof. Dr. RUSUDAN TSURTSUMIA, Rector, V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire Director, International Research Center for Today people all over the world are Traditional Polyphony singing Georgian polyphonic songs. The num- ber of scholars interested in this has greatly in- Georgian life has changed greatly since our creased. -

September 2014 Representing Today’S Great Labels This Month's Highlights

CONSUMER INFORMATION SERVICE: NO. 272 SEPTEMBER 2014 REPRESENTING TODAY’S GREAT LABELS THIS MONTH'S HIGHLIGHTS Select Music and Video Distribution Limited 3 Wells Place, Redhill, Surrey RH1 3SL Tel: 01737 645600 Fax: 01737 644065 George Frideric HANDEL Highlight of the month Arias Radamisto: Quando mai, spietata sorte Alcina: Mi lusinga il dolce affetto; Verdi prati; Stà nell’Ircana; Hercules: There in myrtle shades reclined; Cease, ruler of the day, to rise; Where shall I fly? Giulio Cesare in Egitto: Cara speme, questo core Ariodante: Con l’ali di costanza; Scherza infida!; Dopo notte Alice Coote The English Concert, Harry Bicket Hyperion is delighted to present a tour de force from the supreme mezzo-soprano of today, Alice Coote, accompanied by The English Concert and Harry Bicket, making their Hyperion debut. Coote performs a selection of Handel’s greatest arias from opera and CDA67979 oratorio, employing an extraordinary range of vocal and dramatic colour, tone and emotion to produce triumphant and moving interpretations of these masterpieces. Piano Sonatas Nikolai MEDTNER: Skazki, Op. 20; Sonata in B flat minor ‘Sonata Romantica’, Op. 53, No. 1 Sergei RACHMANINOV: Variations on a theme of Corelli; Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Steven Osborne Steven Osborne has become increasingly admired for his performances and recordings of Russian romantic piano music, playing with a remarkable level of authority and a rare combination of technical ease, tonal CDA67936 lustre and idiomatic identification. Here he presents an impressive selection from two masters who lived and worked contemporaneously. Both were renowned concert pianists, and both wrote superbly for their instrument.