Caecilia May 1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

2016 Annual Report 3 4 Delaware State Police 2016 Annual Report 5 6 Delaware State Police Executive Staff

The 2016 Delaware State Police Annual Report is dedicated to the members of the Delaware State Police who have made the ultimate sacrifice while protecting the citizens and visitors of the State of Delaware. Patrolman Francis Ryan Sergeant Thomas H. Lamb Trooper Paul H. Sherman Corporal Leroy L. Lekites Corporal James D. Orvis Corporal Raymond B. Wilhelm Trooper William F. Mayer Trooper First Class Harold B. Rupert Trooper Robert A. Paris Colonel Eugene B. Ellis Trooper William C. Keller Trooper Ronald L. Carey Trooper David C. Yarrington Trooper George W. Emory Lieutenant William I. Jearman Corporal David B. Pulling Trooper Kevin J. Mallon Trooper Gerard T. Dowd Corporal Robert H. Bell Corporal Francis T. Schneible Trooper Sandra M. Wagner Corporal Frances M. Collender Corporal Christopher M. Shea 2 Delaware State Police Mission Statement To enhance the quality of life for all Delaware citizens and visitors by providing professional, competent and compassionate law enforcement services. HONOR INTEGRITY COURAGE LOYALTY ATTITUDE DISCIPLINE SERVICE Photo by: Elisa Vassas 2016 Annual Report 3 4 Delaware State Police 2016 Annual Report 5 6 Delaware State Police Executive Staff Colonel Nathaniel McQueen Lt. Colonel Monroe Hudson Superintendent Deputy Superintendent Major Robert Hudson Major Daniel Meadows Administrative Officer Special Operations Officer Major Galen Purcell Major Melissa Zebley South Operations Officer North Operations Officer 2016 Annual Report 7 Table of Contents Mission Statement ..............Page 3 Office -

PUBLIC NOTICE CONVERSE COUNTY, WYOMING in Accordance with W.S

PUBLIC NOTICE CONVERSE COUNTY, WYOMING In accordance with W.S. 18-3-516, the following is a complete listing of all fulltime employees and elected officials of Converse County. Salaries are gross yearly salaries and do not reflect any fringe benefits or overtime compensation: Alvarado, Adam, Detention LT $68,394.06; Alvarado, Daniel, Patrol Deputy $56,225.32; Ayers, Earl, Operator $49,295.98; Becker, Clinton, Sheriff $97,600; Blomberg, Kelli, Attorney $104,999.95; Boespflug, Alex, PS Telecommunicator $43,596.80; Bowen, James, Operator $51,792; Brammer, Jeffery Detention Officer $45,186; Bright, Robin Detention SGT $63,181.02; Carr, Frances, Clerk $41,529.60; Carr, Geri, Clerk $55,654.07; Carr, Patricia, Clerk $45,580.63; Caskey, Christopher, Tech Svc. Dir. $86,000; Cathcart, Carly, PS Telecommunicator $41,600.04; Chamberlain, Joel, Operator $39,991.64; Colling, Michael, Commissioner $37,800; Cooper, Vere, Comm Supervisor $64,000; Dalgarn, Russel, Emergency Mgr. $71,426.75; Davies, Mike Operator $46,337.09; Davis, Robert, Operator $38,480; Dexter, Mark, Patrol Deputy $66,809.59; Doyle, Sara, PS Telecommuter $37,502.40; Dwyer, Corey, Patrol Deputy $59,666.75; Dyess, Courtney, Receptionist $33,600.04; Eller, Michael, Operator $48,831.59;Florence, David, Detention Officer $52,945; Gabert, Harley, Operator $41,019.24; Gallagher, Jamie, Detention Officer $50,142.08; Grant, Richard Jr, Commissioner $37,800; Gregersen, Stephen, Attorney $103,492.44; Guenther, Kenneth, Operator $38,480; Gushurst, Don, Maint. Dir. $57,623.71; Gilliam, Whitney, PS Telecommunicator $37,502.40; Harris, Barbara, Deputy Dist. Court Clerk $61,509.55; Herrera, Paul, Mechanic $58,559.07; Hinckley, Jim, Operator $57,883.07; Hinckley, Katy, Detention Officer $44,300; Hinckley, Thomas, Operator $38,480; Hinton, Christopher, Dep. -

RISURREZIONE Dramma in Four Acts - Libretto by Cesare Hanau from the Novel by Leo Tolstoy Publisher: Casa Ricordi Milano

7866.02 (DDD) Franco Alfano (Naples, 1875 – Sanremo, 1954) RISURREZIONE Dramma in four acts - Libretto by Cesare Hanau from the novel by Leo Tolstoy Publisher: Casa Ricordi Milano Katerina Mihaylovna (Katyusha) Anne Sophie Duprels Prince Dimitri Ivanovich Nehlyudov Matthew Vickers Simonson Leon Kim Sofia Ivanovna Francesca Di Sauro Matryona Pavlovna / Anna Romina Tomasoni An old maidservant Nadia Pirazzini Vera / Korablyova Ana Victoria Pitts Fenyichka Barbara Marcacci The Hunchback Filomena Pericoli The Redhead Nadia Sturlese A woman Silvia Capra Kritzlov / Second peasant Lisandro Guinis Chief Guard Gabriele Spina Guard Giovanni Mazzei Train-station officer Nicolò Ayroldi Officer / First peasant Nicola Lisanti Muzhik Egidio Massimo Naccarato Cossack Antonio Montesi Fedia Giulia Bruni First female prisoner Delia Palmieri Second female prisoner Monica Marzini Third female prisoner Giovanna Costa Chorus Livia Sponton, Sabina Beani, Katja De Sarlo, Nadia Pirazzini Orchestra e Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Conductor: Francesco Lanzillotta - Chorus Master: Lorenzo Fratini Recording: MASClassica Audio Recording - Claudio Speranzini, Antonio Martino Recorded at: Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, 17th and 21st January 2020 Tracklist Cd 1 46:34 Act I 01 Piano, che non si versi (Housekeeper, Maidservant, Katyusha) 02:54 02 Cristo è risuscitato (Housekeeper, Maidservant, Katyusha, Chorus) 04:45 03 Dimitri, figliuol mio (Sofia, Dimitri) 02:10 04 Tu sei cambiato tanto (Sofia, Dimitri, Housekeeper, Katyusha) 02:24 05 Qualcuno là in giardino? -

A Cta ΠCumenica

2020 N. 2 ACTA 2020 ŒCUMENICA INFORMATION SERVICE OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN UNITY e origin of the Pontical Council for Promoting Christian Unity is closely linked with the Second Vatican Council. On 5 June 1960, Saint Pope John XXIII established a ‘Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity’ as one of the preparatory commissions for the Council. In 1966, Saint Pope Paul VI conrmed the Secretariat as a permanent dicastery CUMENICA of the Holy See. In 1974, a Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews was established within the Secretariat. In 1988, Saint Pope John Paul II changed the Secretariats status to Pontical Council. Œ e Pontical Council is entrusted with promoting an authentic ecumenical spirit in the Catholic Church based on the principles of Unitatis redintegratio and the guidelines of its Ecumenical Directory rst published in 1967, and later reissued in 1993. e Pontical Council also promotes Christian unity by strengthening relationships CTA with other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, particularly through A theological dialogue. e Pontical Council appoints Catholic observers to various ecumenical gatherings and in turn invites observers or ‘fraternal delegates’ of other Churches or Ecclesial Communities to major events of the Catholic Church. Front cover Detail of the icon of the two holy Apostles and brothers Peter and Andrew, symbolizing the Churches of the East and of the West and the “brotherhood rediscovered” (UUS 51) N. 2 among Christians on their way towards unity. (Original at the Pontical -

For People Whose Bowels "Bellyache" Their Brains HISPERING Jennies" of the G

SOUTH BEND PUBLIC L1BRA1Y, 1 304 S.MAIN ST., CITY. SIXTY MILLION JOBS NOT SO MANY WHEN "WHITE COLLAR" BOYS GET MOSCLED IN SERVICE OUTWEIGHS SOLIDS FRIDAY, MARCH 16th, 1945 *££??*« FACTORY HANOS ONLY 25% of NEEOFOL at NATION'S RESIDENT ROOSEVELT'S 60,000,000 post the president wasn't talking so big after all. It ELIEVE IT war job challenge, thrown at the country meant only about 8,000,000 more jobs than pre P mid-campaign, and which the opposition war, all manner of jobs considered, and these at OR ELSE undertook to laugh down, has now been taken up gainful employment instead of WPA. by American industry to the tune of 56,000,000 Notwithstanding the greatly increased labor ME A T O' THE COCONUT —and out of the wash conies the knowledge that (On Page Four) -.-• BY -:- SILAS WITHERSPOON I Conquered Countries Finger Noses at Rescuers "Herm New- OT Russia, not Poland, or Holland, or Ar please, and already has the "big three" wonder some and Al. "GO FEATHER YOUR gentina, but France appears more and ing just how big was their possible mistakes Doyle are N more the big stumbling block on the road when after Africa, they took on Gen. Charles de plannin' to NEST" MADE G.O.P, to post-war peace. She'is getting cockey as you Gaulle, self-setup leader of the Free French un quit their jobs ANTHEM BY AUTHOR in the court derground, and sort of passed house, come I CAUSE AND EFFECT! up Gen. Henry Honore Gi- OF NEW COURT LAW April 2nd, an' raud. -

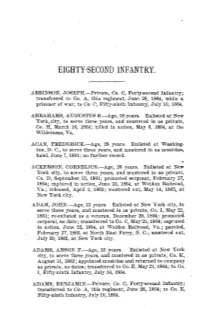

Eighty-Second Infantry

EIGHTY-SECOND INFANTRY. ABBINSON, JOSEPH.—Private, Oo. 0, Forty-second Infantry; transferred to Co. A, this regiment, June 28, 1864, while a prisoner of war; to Oo. O, Fifty-ninth Infantry, July 10, 1864. ABRAHAMS, AUGUSTUS S.—Age, 18 years. Enlisted at New York, city, to serve three years, and mustered in as private, Co. H, March 16, 1864; killed in action, May 6, 1864, at the Wilderness, Ya. ACAN, FREDERICK.—Age, 28 years. Enlisted at Washing• ton, D. C, to serve three years, and mustered in as musician, band, June 7,1861; no further record. • ACKERSON, CORNELIUS.—Age, 26 years. Enlisted at New York city, to serve three years, and mustered in as private, Co. D, September 15, 1861; promoted sergeant, February 27, 1864; captured in action, June 22, 1861, at Weldon Railroad, Va.; released, April 1, 1865; mustered out, May 11, 1865, at New York city. ADAM, JOHN.—Age, 21 years. Enlisted at New York city, to serve tbree years, and mustered in as private, Co. I, May 21, 1861; re-enlisted as a veteran, December 29, 1864; promoted corporal, no date; transferred to Co. C, May 21,1864; captured in action, June 22, 1864, at Weldon Railroad, Va.; paroled, February 27, 1865, at North East Ferry, N. C; mustered out, July 20, 1865, at New York city. ADAMS, ANSON F.—Age, 25 years. Enlisted at New York city, to serve three years, and mustered in as private, Co. K, August 11,1862; appointed musician and returned to company as private, no dates; transferred to Co. E, May 21,1861; to Co. -

CORONATION MEDAL HER Majesty the Queen Has Approved the Institution, to Commemorate the Coronation, of a Silver Medal to Be Known As " the Coronation Medal "

N0. 37] 1021 NEW ZEALAND SUPPLEMENT TO THE New Zealand Gazette OF THURSDAY, 2 JULY 1953 Published by Authority WELLINGTON, FRJµ)AY, 3 JULY 1953 CORONATION MEDAL HER Majesty the Queen has approved the institution, to commemorate the Coronation, of a silver medal to be known as " The Coronation Medal ". It has been struck for issue as a personal souvenir from Her Majesty to persons in the Crown Services and others in the United Kingdom and in other parts of the Commonwealth and Empire. Individuals selected for the award in New Zealand will not receive the medal for several weeks after the Coronation. The following is a description of the medal : Obverse: Effigy of Her Majesty the Queen, Crowned and robed and looking to the observer's right. Reverse: The Royal Cypher " E. R. II " surmounted by the Crown. The inscription " Queen Elizabeth II, Crowned 2nd June, 1953 ", also appears on the reverse. The medal is 1-! in. in diameter, and will be worn suspended from a ribbon 1-! in. in width, dark red in colour, with narrow white stripes at the edges and two narrow dark blue vertical stripes near the centre. The Coronation Medal has been classified as an official medal to be worn, on all occasions on which decorations and medals are worn, on the left breast. In the official list showing the order in which orders, decorations, and medals should be worn it has been placed after war medals, Jubilee and previous Coronation medals, but before efficiency and long service awards. Ladies not in uniform will wear the Coronation Medal on the left shoulder of the dress, the ribbon in this case being in the form of a bow. -

"Duetto a Tre": Franco Alfano's Completion of "Turandot" Author(S): Linda B

"Duetto a tre": Franco Alfano's Completion of "Turandot" Author(s): Linda B. Fairtile Source: Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Jul., 2004), pp. 163-185 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878265 Accessed: 23-06-2017 16:44 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878265?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cambridge Opera Journal This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Fri, 23 Jun 2017 16:44:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge Opera Journal, 16, 2, 163-185 ( 2004 Cambridge University Press DOI- 10.1017/S0954586704001831 Duetto a tre: Franco Alfano's completion of Turandot LINDA B. FAIRTILE Abstract: This study of the ending customarily appended to Giacomo Puccini's unfinished Turandot offers a new perspective on its genesis: that of its principal creator, Franco Alfano. Following Puccini's death in November 1924, the press overstated the amount of music that he had completed for the opera's climactic duet and final scene. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Piano Trios of Nino Rota and the Art Songs of Franco Alfano on Poetry of Rabindranath Tagore Francesco Binda Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE PIANO TRIOS OF NINO ROTA AND THE ART SONGS OF FRANCO ALFANO ON POETRY OF RABINDRANATH TAGORE By FRANCESCO BINDA A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2017 Francesco Binda defended this treatise on February 26, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Timothy Hoekman Professor Directing Treatise André Thomas University Representative Iain Quinn Committee Member Valerie Trujillo Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my father, Germano Binda, whose sacrifices in life gave me the opportunity to undertake the study of piano. The love he gave to his family has been an indelible example for my life. His passion for opera and for the arts was the spark that introduced me to music. I hope and pray that the achievement of this honorable degree may make him proud of my accomplishment. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my major professor, Dr. Timothy Hoekman, who guided me throughout this exceptional journey. His patience, understanding, professionalism, and expertise were indispensable elements toward the accomplishment of this degree. -

Sacramental Woes and Theological Anxiety in Medieval Representations of Marriage

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Elizabeth Churchill University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Churchill, Elizabeth, "When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2229. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2229 For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Two Become One: Sacramental Woes And Theological Anxiety In Medieval Representations Of Marriage Abstract This dissertation traces the long, winding, and problematic road along which marriage became a sacrament of the Church. In so doing, it identifies several key problems with marriage’s ability to fulfill the sacramental criteria laid out in Peter Lombard’s Sentences: that a sacrament must signify a specific form of divine grace, and that it must directly bring about the grace that it signifies. While, on the basis of Ephesians 5, theologians had no problem identifying the symbolic power of marriage with the spiritual union of Christ and the Church, they never fully succeeded in locating a form of effective grace, placing immense stress upon marriage’s status as a signifier. As a result, theologians and canonists found themselves unable to deal with several social aspects of marriage that threatened this symbolic capacity, namely concubinage and the remarriage of widows and widowers. -

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY's PUBLICATIONS General Editors

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: Madge Dresser Peter Fleming Roger Leech VOLUME 58 ROBERT STURMY'S COMMERCIAL EXPEDITION TO THE MEDITERRANEAN (1457/8) ROBERT STURMY'S COMMERCIAL EXPEDITION TO THE MEDITERRANEAN (1457/8) With Editions of the Trial of the Genoese before King and Council and of other sources By Stuart Jenks With a Preface by Evan Jones Published by The Bristol Record Society 2006 ISBN 0 901538 28 0 © S tuart J enks No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage or retrieval system. The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant Venturers. BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS. Peter Fleming, Ph.D. Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming Treasurer: Mr William Evans The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty eight major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. All the volumes, together with their authoritative introductions, are edited by scholars who are experts in their chosen field. Recent volumes have included: Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth-Century Slave Trade to America (Vols.