Renal Papillary Necrosis in Infancy PETER HUSBAND* and K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

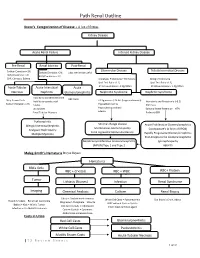

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

Acute Tubular Necrosıs After Nephrectomy: Case Presentatıon

Case Report JOJ Case Stud Volume 7 Issue 1 - May 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ebru Canakci DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2018.07.555703 Acute Tubular Necrosıs after Nephrectomy: Case Presentatıon Ebru Canakci1*, Ahmet Karatas2, Ahmet Gultekin1, Zubeyir Cebeci1, Ilker Coskun1 and Anıl Kılınc1 1Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Ordu University, Turkey 2Department of Internal Medicine & Nephrology, Ordu University, Turkey Submission: May 07, 2018; Published: May 18, 2018 *Corresponding author: Ebru Canakci, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Ordu University, Ordu, Turkey, Email: Abstract ATN, contrary to prerenal azotemia, is not immediately cured upon the recovery of renal perfusion. In its severe form, renal hypoperfusion leads Acute renal failure (ARF) has a clinical presentation with declining renal function and glomerular filtration rate within hours-days. Ischemic trauma, severe hypovolemia, sepsis and severe burns. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is one of the frequently encountered causes of morbidity and mortalityto bilateral in renal hospitals. cortical The necrosis aim of this and study irreversible is to present renal the insufficiency. case with ATN Ischemic after major ATN often surgery develops and subsequent as a result permanent of major surgical kidney injuryintervention, in light of the information from the literature. Keywords: Nephrectomy; Acute Tubular Necrosis; Hemodialysis Introductıon and Objectıve to endogenous or exogenous toxins. Toxins cause intrarenal Acute renal failure (ARF) has a clinical presentation with vasoconstriction, direct tubular toxicity and/or intratubular obstruction and thus lead to ARF [4]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) hours-days. Although there are several differences in the declining renal function and glomerular filtration rate within is one of the frequently encountered causes of morbidity and mortality in hospitals. -

Effects of Bodybuilding Supplements on the Kidney

Ali et al. BMC Nephrology (2020) 21:164 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01834-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Effects of bodybuilding supplements on the kidney: A population-based incidence study of biopsy pathology and clinical characteristics among middle eastern men Alaa Abbas Ali1, Safaa E. Almukhtar2†, Dana A. Sharif3†, Zana Sidiq M. Saleem4†, Dana N. Muhealdeen1 and Michael D. Hughson1* Abstract Background: The incidence of kidney diseases among bodybuilders is unknown. Methods: Between January 2011 and December 2019, the Iraqi Kurdistan 15 to 39 year old male population averaged 1,100,000 with approximately 56,000 total participants and 25,000 regular participants (those training more than 1 year). Annual age specific incidence rates (ASIR) with (95% confidence intervals) per 100,000 bodybuilders were compared with the general age-matched male population. Results: Fifteen male participants had kidney biopsies. Among regular participants, diagnoses were: focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), 2; membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN), 2; post-infectious glomeruonephritis (PIGN), 1; tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), 1; and nephrocalcinosis, 2. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) was diagnosed in 5 regular participants and 2 participants training less than 1 year. Among regular participants, anabolic steroid use was self- reported in 26% and veterinary grade vitamin D injections in 2.6%. ASIR for FSGS, MGN, PIGN, and TIN among regular participants was not statistically different than the general population. ASIR of FSGS adjusted for anabolic steroid use was 3.4 (− 1.3 to 8.1), a rate overlapping with FSGS in the general population at 2.0 (1.2 to 2.8). ATN presented as exertional muscle injury with myoglobinuria among new participants. -

An Unusual Cause of Glomerular Hematuria and Acute Kidney Injury in a Chronic Kidney Disease Patient During Warfarin Therapy Clara Santos, Ana M

11617 14/5/13 12:11 Página 400 http://www.revistanefrologia.com casos clínicos © 2013 Revista Nefrología. Órgano Oficial de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología An unusual cause of glomerular hematuria and acute kidney injury in a chronic kidney disease patient during warfarin therapy Clara Santos, Ana M. Gomes, Ana Ventura, Clara Almeida, Joaquim Seabra Department of Nephrology. Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia. Vila Nova de Gaia (Portugal) Nefrologia 2013;33(3):400-3 doi:10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2012.Oct.11617 ABSTRACT Un caso inusual de hematuria glomerular y fracaso renal agudo en un paciente con enfermedad renal crónica Warfarin is a well-established cause of gross hematuria. durante terapia con warfarina However, impaired kidney function does not occur RESUMEN except in the rare instance of severe blood loss or clot La warfarina es una causa muy conocida de hematuria ma- formation that obstructs the urinary tract. It has been croscópica. Sin embargo, el deterioro de la función renal no ocurre salvo en el caso inusual de gran pérdida de sangre o recently described an entity called warfarin-related formación de coágulos que obstruyen el tracto urinario. Re- nephropathy, in which acute kidney injury is caused by cientemente se ha descrito una entidad denominada nefro- glomerular hemorrhage and renal tubular obstruction patía relacionada con la warfarina en la que el fracaso renal by red blood cell casts. We report a patient under agudo es provocado por hemorragia glomerular y obstruc- warfarin treatment with chronic kidney disease, ción tubular renal por cilindros de glóbulos rojos. Exponemos macroscopic hematuria and acute kidney injury. -

Acute Toxic Nephropathies: Clinical Pathologic Correlations - ROBERT C

ANNALS OF CLINICAL AND LABORATORY SCIENCE, Vol. 6, No. 6 Copyright © 1976, Institute for Clinical Science Acute Toxic Nephropathies: Clinical Pathologic Correlations - ROBERT C. MUEHRCKE, M.D.,* FREDERICK I. VOLINI, M.D.,f ARTHUR M. MORRIS, M.D.,f JOSEPH B. MOLES, M.D.,f and ARTHUR G. LAWRENCE, M.D.,f *West Suburban Kidney Center and fWest Suburban Hospital, Oak Park, IL 60302 ABSTRACT Man’s ever increasing exposure to numerous drugs and chemicals, which are the results of medical and industrial progress, produces a by-product of acute toxic nephropathies. These include acute toxic renal failure, drug- induced acute oliguric renal failure, acute hemorrhagic glomerulonephritis, nephrotic syndrome, tubular disturbances and potassium deficiency. In depth information is provided for the previously mentioned disorders. Introduction have extremely vascular renal medullae Acute toxic nephropathy is a by and rete mirabile that function in the product of man’s ever increasing expo final dilution and concentration of the sure to a vast array of various chemicals urine. This complex mechanism results and drugs that result from industrial and in hypertonicity of the renal interstitium medical progress. The kidney, with its with concentration of nephrotoxic chemi rich blood supply, numerous enzyme sys cals, biologic products and drugs. tems and superior excretory function, is In our experience, approximately 25 especially vulnerable to the adverse ef percent of all patients with acute oliguria fects of chemicals, biologic products and have renal failure induced by drugs or drugs.44,226 The kidneys comprise 0.4 chem icals.188 The other main clinical percent of the total body weight and re syndrome of toxic nephropathy include quire a high oxygen consumption. -

In-Depth Review AKI Associated with Macroscopic Glomerular Hematuria: Clinical and Pathophysiologic Consequences

In-Depth Review AKI Associated with Macroscopic Glomerular Hematuria: Clinical and Pathophysiologic Consequences Juan Antonio Moreno,* Catalina Martı´n-Cleary,* Eduardo Gutie´rrez,† Oscar Toldos,‡ Luis Miguel Blanco-Colio,* Manuel Praga,† Alberto Ortiz,* § and Jesu´s Egido* § Summary *Division of Nephrology and Hematuria is a common finding in various glomerular diseases. This article reviews the clinical data on glomerular Hypertension, IIS- hematuria and kidney injury, as well as the pathophysiology of hematuria-associated renal damage. Although Fundacio´n Jime´nez glomerular hematuria has been considered a clinical manifestation of glomerular diseases without real Dı´az, Autonoma consequences on renal function and long-term prognosis, many studies performed have shown a relationship University, Madrid, Spain; †Division of between macroscopic glomerular hematuria and AKI and have suggested that macroscopic hematuria-associated Nephrology and AKI is related to adverse long-term outcomes. Thus, up to 25% of patients with macroscopic hematuria– ‡Department of associated AKI do not recover baseline renal function. Oral anticoagulation has been associated with glomerular Pathology, Instituto de macrohematuria–related kidney injury. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms may account for the tubular injury Investigacio´n Hospital found on renal biopsy specimens. Mechanical obstruction by red blood cell casts was thought to play a role. More 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; and recent evidence points to cytotoxic effects of oxidative stress induced by hemoglobin, heme, or iron released from §Fundacion Renal red blood cells. These mechanisms of injury may be shared with hemoglobinuria or myoglobinuria-induced AKI. Inigo~ Alvarez de Heme oxygenase catalyzes the conversion of heme to biliverdin and is protective in animal models of heme Toledo/Instituto toxicity. -

Unique Proximal Tubular Cell Injury and the Development of Acute

Fujigaki et al. BMC Nephrology (2017) 18:339 DOI 10.1186/s12882-017-0756-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Unique proximal tubular cell injury and the development of acute kidney injury in adult patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome Yoshihide Fujigaki1*, Yoshifuru Tamura2, Michito Nagura2, Shigeyuki Arai2, Tatsuru Ota2, Shigeru Shibata2, Fukuo Kondo3, Yutaka Yamaguchi3 and Shunya Uchida2 Abstract Background: Adult patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS) are often associated with acute kidney injury (AKI). To assess the mechanisms of AKI, we examined whether tubular cell injuries unique to MCNS patients exist. Methods: We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical data and tubular cell changes using the immunohistochemical expression of vimentin as a marker of tubular injury and dedifferentiation at kidney biopsy in 37 adult MCNS patients. AKI was defined by the criteria of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines for AKI. Results: Thirteen patients (35.1%) were designated with AKI at kidney biopsy. No significant differences in age, history of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diuretics use, proteinuria, and serum albumin were noted between the AKI and non- AKI groups. Urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (uNAG) and urinary alpha1-microglobulin (uA1MG) as markers of tubular injury were increased in both groups, but the levels were significantly increased in the AKI group compared with the non- AKI group. The incidence of vimentin-positive tubules was comparable between AKI (84.6%) and non-AKI (58.3%) groups, but vimentin-positive tubular area per interstitial area was significantly increased in the AKI group (19.8%) compared with the non-AKI group (6.8%) (p = 0.011). -

Sorting the Alphabet Soup of Renal Pathology: a Review

Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology ] (2016) ]]]–]]] Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology journal homepage: www.cpdrjournal.com Sorting the Alphabet Soup of Renal Pathology: A Review Sheilah M. Curran-Melendez, MDa,n, Matthew S. Hartman, MDa, Matthew T. Heller, MDb, Nancy Okechukwu, MDa a Department of Radiology, Allegheny General Hospital, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, PA b University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Department of Radiology, Pittsburgh, PA Diseases of the kidney often have their names shortened, creating an arcane set of acronyms which can be confusing to both radiologists and clinicians. This review of renal pathology aims to explain some of the most commonly used acronyms within the field. For each entity, a summary of the clinical features, pathophysiology, and radiological findings is included to aid in the understanding and differentiation of these entities. Discussed topics include acute cortical necrosis, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, angiomyolipoma, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, acute tubular necrosis, localized cystic renal disease, multicystic dysplastic kidney, multilocular cystic nephroma, multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma, medullary sponge kidney, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, renal papillary necrosis, transitional cell carcinoma, and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. & 2016 Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Pathology Diseases of the kidney often have their names shortened, The underlying pathophysiology of ACN is poorly understood, creating an arcane set of acronyms that can be confusing to both but it involves ischemic injury to the renal cortex, primarily the radiologists and clinicians. This review of renal pathology aims to renal tubules, because of arterial insufficiency. The renal medulla explain some of the most commonly used acronyms within the and papilla are spared because of lower oxygen tension in this field. -

Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury

Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury Pamela Parker Ultrasound Specialty Manager Aims • What is Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)? • Discuss the implications of AKI for USS • Revisit Resistive Index (RIs) Why? The FACTS • AKI is responisble for a 20-30% in-patient mortality rate • The mortality rate varies greatly depending on the severity, setting, and many patient- related factors but it is a KILLER. AKI Explained • The older term is 'acute renal failure' (ARF). • Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a rapid deterioration of renal function, resulting in inability to maintain fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance. AKI Explained • It is detected and monitored by serial serum creatinine readings primarily, which rise acutely • The definition of acute kidney injury has changed in recent years, and detection is now mostly based on monitoring creatinine levels, with or without urine output. Acute Kidney Injury, adding insult to injury (2009) • 2009 UK National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) found serious deficiencies in patients who died with a diagnosis of AKI. • Only 50% of patients received good medical care Why NICE? • Acute kidney injury is seen in 13–18% of all people admitted to hospital, with older adults being particularly affected. • The costs to the NHS of acute kidney injury (excluding costs in the community) are estimated to be between £434 million and £620 million per year, • More than the costs associated with breast cancer, or lung and skin cancer combined. Why NICE? • Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management of acute kidney injury up to the point of renal replacement therapy • NICE guideline August 2013 Why NICE? • Estimated that improving care could save 12,000 lives in England and save the NHS £150 million per year NICE Guideline 2013 Ultrasound Offer urgent ultrasound of the urinary tract to patients with acute kidney injury who: – have no identified cause of acute kidney injury, or – are at risk of urinary tract obstruction. -

Renal Failure • It May Be Prerenal, Renal Or Postrenal

Urinary System Pathology Kidney • The essential requirements for normal renal function are: adequate perfusion with blood (pressure >60 mm Hg), adequate functional renal tissue, and normal elimination of urine from the urinary tract Renal failure • It may be prerenal, renal or postrenal. PRERENAL FAILURE The kidneys do not have enough blood. RENAL FAILURE It is characterized by a disorder in the kidney parenchyma. POSTRENAL FAILURE It occurs when urine excretion is prevented. • In such cases, imbalance of acid-base and salt-water are formed, and residual products cannot be removed from the body. • The most important indicator of renal insufficiency is the amount of urea that cannot be removed from the body. • Urea itself does not have any detrimental effect, but other disorders in urinary function lead to uremia syndrome, with very important clinical signs. • In renal disorders blood vessels, glomeruli, tubules and interstitium are affected. • Although the kidneys constitute only about 0.5% of body weight, they receive 20-25% of cardiac output. Renal disease, Renal failure, and Uremia • Renal disease, which encompasses any deviation from normal renal structure or function, is usually subclinical. • Severe renal disease may lead to renal failure, which is typically divided into acute and chronic forms. • Acute renal failure (ARF) is characterized by rapid onset of oliguria or anuria and azotemia; it may result from acute glomerular or interstitial injury or from Acute Tubulus Necrosis (ATN), and is often reversible. • Chronic renal failure (CRF) is the end result of many chronic renal diseases, is usually irreversible, and is characterized by prolonged duration of signs of uremia. -

Chapter 11. Chemotherapy and Kidney Injury

Chapter 11. Chemotherapy and Kidney Injury † † Ilya G. Glezerman, MD,* and Edgar A. Jaimes, MD* *Renal Service, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; and †Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York INTRODUCTION cell apoptosis and production of ROS (3). Cisplatin is excreted and concentrated in the kidneys entering re- By January 1, 2011, 4,594,732 people in the United nal tubular cells via organic cation transporter 2, States carried the diagnosis of invasive malignancy. which is kidney specific(3). On the other hand, with significant advances in Initialrenaltoxicitymanifestsasadecreaseinrenal anticancer therapies, the 5-year survival for cancer blood flow and subsequent decline in GFR within patients has increased from 48.9% in 1975–1979 to 3hoursofcisplatinadministration.Thesechangesare 68.5% in 2006 (1). These statistics show that a sig- probably due to increased vascular resistance sec- nificant percentage of the population is likely to be ondary to tubulo-glomerular feedback and increased exposed to chemotherapy and suffer various short- sodium chloride delivery to macula densa. The term and, in case of survivors, long-term adverse decline in GFR appears to be dose dependent. In effects of treatment. a group of patients who received four cycles of Kidneys are vulnerable to the development of drug 100 mg/m2,the51Cr-EDTA–measured GFR de- toxicity due to their role in the metabolism and clined by 11.7%, whereas in patients who received excretion of toxic agents. The kidneys receive close to three cycles of 200 mg/m2, the mean decline was 25% of cardiac output, and the renal tubules and 35.7%. -

Glomerular Hematuria: Cause Or Consequence of Renal Inflammation?

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Glomerular Hematuria: Cause or Consequence of Renal Inflammation? Juan Antonio Moreno 1,2,* , Ángel Sevillano 3, Eduardo Gutiérrez 3, Melania Guerrero-Hue 1,2, Cristina Vázquez-Carballo 1, Claudia Yuste 3, Carmen Herencia 1, Cristina García-Caballero 1, Manuel Praga 3 and Jesús Egido 1,4,* 1 Renal, Vascular and Diabetes Research Laboratory. Fundacion Jimenez Diaz University Hospital-Health Research Institute (FIIS-FJD), Autonoma University of Madrid (UAM), 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (M.G.-H.); [email protected] (C.V.-C.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (C.G.-C.) 2 Department of Cell Biology, Physiology, and Immunology, Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute of Cordoba (IMIBIC), University of Cordoba, 14014 Cordoba, Spain 3 Department of Nephrology, Hospital 12 de Octubre, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (Á.S.); [email protected] (E.G.); [email protected] (C.Y.); [email protected] (M.P.) 4 Spanish Biomedical Research Centre in Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders (CIBERDEM), 28040 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.A.M.); [email protected] (J.E.) Received: 29 March 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 5 May 2019 Abstract: Glomerular hematuria is a cardinal symptom of renal disease. Glomerular hematuria may be classified as microhematuria or macrohematuria according to the number of red blood cells in urine. Recent evidence suggests a pathological role of persistent glomerular microhematuria in the progression of renal disease. Moreover, gross hematuria, or macrohematuria, promotes acute kidney injury (AKI), with subsequent impairment of renal function in a high proportion of patients.