Urinary Tract Disorders in Cattle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point-Of-Care Ultrasound to Assess Anuria in Children

CME REVIEW ARTICLE Point-of-Care Ultrasound to Assess Anuria in Children Matthew D. Steimle, DO, Jennifer Plumb, MD, MPH, and Howard M. Corneli, MD patients to stay abreast of the most current advances in medicine Abstract: Anuria in children may arise from a host of causes and is a fre- and provide the safest, most efficient, state-of-the-art care. Point- quent concern in the emergency department. This review focuses on differ- of-care US can help us meet this goal.” entiating common causes of obstructive and nonobstructive anuria and the role of point-of-care ultrasound in this evaluation. We discuss some indications and basic techniques for bedside ultrasound imaging of the CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS urinary system. In some cases, as for example with obvious dehydration or known renal failure, anuria is not mysterious, and evaluation can Key Words: point-of-care ultrasound, anuria, imaging, evaluation, be directed without imaging. In many other cases, however, diagnosis point-of-care US can be a simple and helpful way to assess urine (Pediatr Emer Care 2016;32: 544–548) volume, differentiate urinary retention in the bladder from other causes, evaluate other pathology, and, detect obstructive causes. TARGET AUDIENCE When should point-of-care US be performed? Because this imag- ing is low-risk, and rapid, early use is encouraged in any case This article is intended for health care providers who see chil- where it might be helpful. Scanning the bladder first answers the dren and adolescents in acute care settings. Pediatric emergency key question of whether urine is present. -

Overactive Bladder: What You Need to Know Whiteboard Animation Transcript with Shawna Johnston, MD and Emily Stern, MD

Obstetrics and Gynecology – Overactive Bladder: What You Need to Know Whiteboard Animation Transcript with Shawna Johnston, MD and Emily Stern, MD Overactive bladder (OAB) is a symptom-based disease state, which includes urinary frequency, nocturia, and urgency, with or without urgency incontinence. Symptoms of a urinary tract infection (UTI) are similar but additionally include dysuria (painful voiding) and hematuria. OAB tends to be a chronic progressive condition, while UTI symptoms are acute and may be associated with fever and malaise. In patients whose symptoms are unclear, urinalysis and urine culture may help rule out infection. If symptoms point to OAB, you should rule out: 1. Neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, dementia, parkinson’s disease, and stroke. 2. Medical disorders such as diabetes, and 3. Prolapse, as women with obstructed voiding, usually from advanced prolapse, can have symptoms that mimic those of OAB. It is important to delineate how OAB symptoms affect a patient’s quality of life. Women with OAB are often socially isolated and sleep poorly. On history, pay attention to lifestyle factors such as caffeine and fluid intake, environmental triggers, and medications that may worsen symptoms like diuretics. Cognitive impairment and diabetes can influence OAB symptoms. Estrogen deficiency worsens OAB symptoms, so menopausal status and hormone use are important to note. Physical exam includes a screening sacral neurologic exam, an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse and a cough stress test to rule out stress urinary incontinence. On pelvic exam, look for signs of estrogen deficiency. Investigations include urinalysis, urine culture, and a post-void residual volume measurement. -

Ideal Conditions for Urine Sample Handling, and Potential in Vitro Artifacts Associated with Urine Storage

Urinalysis Made Easy: The Complete Urinalysis with Images from a Fully Automated Analyzer A. Rick Alleman, DVM, PhD, DABVP, DACVP Lighthouse Veterinary Consultants, LLC Gainesville, FL Ideal conditions for urine sample handling, and potential in vitro artifacts associated with urine storage 1) Potential artifacts associated with refrigeration: a) In vitro crystal formation (especially, calcium oxalate dihydrate) that increases with the duration of storage i) When clinically significant crystalluria is suspected, it is best to confirm the finding with a freshly collected urine sample that has not been refrigerated and which is analyzed within 60 minutes of collection b) A cold urine sample may inhibit enzymatic reactions in the dipstick (e.g. glucose), leading to falsely decreased results. c) The specific gravity of cold urine may be falsely increased, because cold urine is denser than room temperature urine. 2) Potential artifacts associated with prolonged storage at room temperature, and their effects: a) Bacterial overgrowth can cause: i) Increased urine turbidity ii) Altered pH (1) Increased pH, if urease-producing bacteria are present (2) Decreased pH, if bacteria use glucose to form acidic metabolites iii) Decreased concentration of chemicals that may be metabolized by bacteria (e.g. glucose, ketones) iv) Increased number of bacteria in urine sediment v) Altered urine culture results b) Increased urine pH, which may occur due to loss of carbon dioxide or bacterial overgrowth, can cause: i) False positive dipstick protein reaction ii) Degeneration of cells and casts iii) Alter the type and amount of crystals present 3) Other potential artifacts: a) Evaporative loss of volatile substances (e.g. -

Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis

$50. 00 Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis Dennis J. Chew, DVM Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM Clinical Handbook Series Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis Dennis J. Chew, DVM Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM Clinical Handbook Series Preface Urine is that golden body fluid that has the potential to reveal the answers to many of the body’s mysteries. As Thomas McCrae (1870-1935) said, “More is missed by not looking than not knowing.” And so, the authors would like to dedicate this handbook to three pioneers of veterinary nephrology and urology who emphasized the importance of “looking,” that is, the importance of conducting routine urinalysis in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of dogs and cats. To Dr. Carl A. Osborne , for his tireless campaign to convince veterinarians of the importance of routine urinalysis; to Dr. Richard C. Scott , for his emphasis on evaluation of fresh urine sediments; and to Dr. Gerald V. Ling for his advancement of the technique of cystocentesis. Published by The Gloyd Group, Inc. Wilmington, Delaware © 2004 by Nestlé Purina PetCare Company. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Nestlé Purina PetCare Company: Checkerboard Square, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63188 First printing, 1998. Laboratory slides reproduced by permission of Dennis J. Chew, DVM and Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM. This book is protected by copyright. ISBN 0-9678005-2-8 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................1 Part I Chapter 1 Sample Collection ...............................................5 -

Dysuria White Paper

CASE STUDY SUMMARY Management of Dysuria for BPH Surgical Procedures Ricardo Gonzalez, M.D. Medical Director of Voiding Dysfunction at Houston Metro Urology, Houston, Texas Dysuria following Benign Prostatic approach, concentrating on one area without Hyperplasia (BPH) Procedures ‘jumping around.’ Keep the laser at .5 mm away from the tissue when using the GreenLight PV® Transient dysuria following surgical treatment system; and 3 mm or less for the GreenLight of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is not an HPS® and GreenLight XPS® systems. Care must uncommon occurrence regardless of treatment. also be taken at the bladder neck: Identify Many factors may contribute to dysuria after the UOs and trigone, use lower power these procedures, including irritation from the (60-80 watts) and avoid directing energy introduction of the cystoscope; the degree of into the bladder.” tissue necrosis; the surgical modality utilized; the surgical technique employed; and the patient’s condition. This paper will focus on Pre-and Post-Operative Management both pre-procedural as well as post-procedural of Dysuria management of irritative symptoms related to Dr. Ricardo Gonzalez is an expert in the surgical BPH procedures. treatment of BPH with the GreenLight Laser System. “I spend considerable time Contributors to Dysuria educating patients on what to expect after Ricardo Gonzalez, M.D., Medical Director of surgical treatment of BPH, including dysuria,” Voiding Dysfunction at Houston Metro Urology says Dr. Gonzalez. “Proper patient education states, “Inefficient surgical technique can encour- will prevent many unnecessary phone calls age coagulative necrosis, which may increase from patients.” inflammation. This is more likely to be the case Dr. -

Urinary System Diseases and Disorders

URINARY SYSTEM DISEASES AND DISORDERS BERRYHILL & CASHION HS1 2017-2018 - CYSTITIS INFLAMMATION OF THE BLADDER CAUSE=PATHOGENS ENTERING THE URINARY MEATUS CYSTITIS • MORE COMMON IN FEMALES DUE TO SHORT URETHRA • SYMPTOMS=FREQUENT URINATION, HEMATURIA, LOWER BACK PAIN, BLADDER SPASM, FEVER • TREATMENT=ANTIBIOTICS, INCREASE FLUID INTAKE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS • AKA NEPHRITIS • INFLAMMATION OF THE GLOMERULUS • CAN BE ACUTE OR CHRONIC ACUTE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS • USUALLY FOLLOWS A STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTION LIKE STREP THROAT, SCARLET FEVER, RHEUMATIC FEVER • SYMPTOMS=CHILLS, FEVER, FATIGUE, EDEMA, OLIGURIA, HEMATURIA, ALBUMINURIA ACUTE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS • TREATMENT=REST, SALT RESTRICTION, MAINTAIN FLUID & ELECTROLYTE BALANCE, ANTIPYRETICS, DIURETICS, ANTIBIOTICS • WITH TREATMENT, KIDNEY FUNCTION IS USUALLY RESTORED, & PROGNOSIS IS GOOD CHRONIC GLOMERULONEPHRITIS • REPEATED CASES OF ACUTE NEPHRITIS CAN CAUSE CHRONIC NEPHRITIS • PROGRESSIVE, CAUSES SCARRING & SCLEROSING OF GLOMERULI • EARLY SYMPTOMS=HEMATURIA, ALBUMINURIA, HTN • WITH DISEASE PROGRESSION MORE GLOMERULI ARE DESTROYED CHRONIC GLOMERULONEPHRITIS • LATER SYMPTOMS=EDEMA, FATIGUE, ANEMIA, HTN, ANOREXIA, WEIGHT LOSS, CHF, PYURIA, RENAL FAILURE, DEATH • TREATMENT=LOW NA DIET, ANTIHYPERTENSIVE MEDS, MAINTAIN FLUIDS & ELECTROLYTES, HEMODIALYSIS, KIDNEY TRANSPLANT WHEN BOTH KIDNEYS ARE SEVERELY DAMAGED PYELONEPHRITIS • INFLAMMATION OF THE KIDNEY & RENAL PELVIS • CAUSE=PYOGENIC (PUS-FORMING) BACTERIA • SYMPTOMS=CHILLS, FEVER, BACK PAIN, FATIGUE, DYSURIA, HEMATURIA, PYURIA • TREATMENT=ANTIBIOTICS, -

Renal Papillary Necrosis in Infancy PETER HUSBAND* and K

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.48.2.116 on 1 February 1973. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1973, 48, 116. Renal papillary necrosis in infancy PETER HUSBAND* and K. A. HOWLETT From the Departments of Paediatrics and Radiology, Charing Cross Group of Hospitals, Fulham Hospital, London Husband, P., and Howlett, K. A. (1973). Archives of Disease in Childhood, 48, 116. Renal papillary necrosis in infancy. Two infants developed renal papillary necrosis after acute illnesses associated with dehydration. After a short oliguric phase there was a longer phase characterized by impaired urinary concen- tration, hyponatraemia, metabolic acidosis, and a raised blood urea. Intravenous urograms showed contrast collecting in the papillae, with subsequent sinus formation extending into the medulla. In one case impaired urinary concentration was still present 21 months after the initial illness. Renal papillary necrosis was originally described admitted to hospital 9 days later after he had been by Friedreich (1877) in a man aged 70 years. found in his cot, grey, with respiratory distress and a Since then the majority of further cases reported high temperature. 3 days before he had diarrhoea and have also been in adults. It has been thought to vomiting for 24 hours but subsequently tolerated feeds be uncommon and usually to have a fatal outcome of full cream Cow and Gate milk, 180 ml 5 times a day. He was again extremely ill: temperature 40 3 °C, pale, copyright. in infancy and childhood (Davies, Kennedy, and cyanosed with a rapid respiratory rate, but not dehydra- Roberts, 1969). In the newborn infant renal ted. -

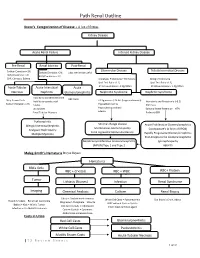

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

Acute Tubular Necrosıs After Nephrectomy: Case Presentatıon

Case Report JOJ Case Stud Volume 7 Issue 1 - May 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ebru Canakci DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2018.07.555703 Acute Tubular Necrosıs after Nephrectomy: Case Presentatıon Ebru Canakci1*, Ahmet Karatas2, Ahmet Gultekin1, Zubeyir Cebeci1, Ilker Coskun1 and Anıl Kılınc1 1Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Ordu University, Turkey 2Department of Internal Medicine & Nephrology, Ordu University, Turkey Submission: May 07, 2018; Published: May 18, 2018 *Corresponding author: Ebru Canakci, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Ordu University, Ordu, Turkey, Email: Abstract ATN, contrary to prerenal azotemia, is not immediately cured upon the recovery of renal perfusion. In its severe form, renal hypoperfusion leads Acute renal failure (ARF) has a clinical presentation with declining renal function and glomerular filtration rate within hours-days. Ischemic trauma, severe hypovolemia, sepsis and severe burns. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is one of the frequently encountered causes of morbidity and mortalityto bilateral in renal hospitals. cortical The necrosis aim of this and study irreversible is to present renal the insufficiency. case with ATN Ischemic after major ATN often surgery develops and subsequent as a result permanent of major surgical kidney injuryintervention, in light of the information from the literature. Keywords: Nephrectomy; Acute Tubular Necrosis; Hemodialysis Introductıon and Objectıve to endogenous or exogenous toxins. Toxins cause intrarenal Acute renal failure (ARF) has a clinical presentation with vasoconstriction, direct tubular toxicity and/or intratubular obstruction and thus lead to ARF [4]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) hours-days. Although there are several differences in the declining renal function and glomerular filtration rate within is one of the frequently encountered causes of morbidity and mortality in hospitals. -

Management of the Nephrotic Syndrome GAVIN C

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.43.228.257 on 1 April 1968. Downloaded from Personal Practice* Arch. Dis. Childh., 1968, 43, 257. Management of the Nephrotic Syndrome GAVIN C. ARNEIL From the Department of Child Health, University of Glasgow The nephrotic syndrome may be defined as gross (3) Idiopathic nephrosis. This may be re- proteinuria, predominantly albuminuria, with con- garded either as a primary disease, or as a secondary sequent selective hypoproteinaemia; usually accom- disorder, with the primary cause or causes still panied by oedema, ascites, and hyperlipaemia, and unknown. It is the common form of nephrosis in sometimes by systemic hypertension, azotaemia, or childhood, but the less common in adult patients. excessive erythrocyturia. Unless otherwise specified, the present discussion concerns idiopathic nephrosis. Grouping of Nephrotic Syndrome The syndrome falls into three groups. Assessment of the Case Full history and examination helps to exclude (1) Congenital nephrosis. A group of dis- many secondary forms of the disease. Blood orders present at and presenting soon after birth, pressure is recorded employing as broad a cuff as which are familial and may be acquired or inherited. practicable, and the width of the cuff used is Persistent oedema attracts attention in the first recorded as of importance in comparative estima- weeks of life. The disease may be rapidly lethal, tions. A careful search for concomitant infection but occasionally the patient will survive for a year is made, particularly to exclude pneumococcal copyright. or more without fatal infection or lethal azotaemia. peritonitis or low grade cellulitis. In a patient The disease pattern tends to run true within a previously treated elsewhere, evidence of steroid family. -

Effects of Bodybuilding Supplements on the Kidney

Ali et al. BMC Nephrology (2020) 21:164 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01834-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Effects of bodybuilding supplements on the kidney: A population-based incidence study of biopsy pathology and clinical characteristics among middle eastern men Alaa Abbas Ali1, Safaa E. Almukhtar2†, Dana A. Sharif3†, Zana Sidiq M. Saleem4†, Dana N. Muhealdeen1 and Michael D. Hughson1* Abstract Background: The incidence of kidney diseases among bodybuilders is unknown. Methods: Between January 2011 and December 2019, the Iraqi Kurdistan 15 to 39 year old male population averaged 1,100,000 with approximately 56,000 total participants and 25,000 regular participants (those training more than 1 year). Annual age specific incidence rates (ASIR) with (95% confidence intervals) per 100,000 bodybuilders were compared with the general age-matched male population. Results: Fifteen male participants had kidney biopsies. Among regular participants, diagnoses were: focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), 2; membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN), 2; post-infectious glomeruonephritis (PIGN), 1; tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), 1; and nephrocalcinosis, 2. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) was diagnosed in 5 regular participants and 2 participants training less than 1 year. Among regular participants, anabolic steroid use was self- reported in 26% and veterinary grade vitamin D injections in 2.6%. ASIR for FSGS, MGN, PIGN, and TIN among regular participants was not statistically different than the general population. ASIR of FSGS adjusted for anabolic steroid use was 3.4 (− 1.3 to 8.1), a rate overlapping with FSGS in the general population at 2.0 (1.2 to 2.8). ATN presented as exertional muscle injury with myoglobinuria among new participants. -

The Nephrotic Syndrome in Early Infancy: a Report of Three Cases* by H

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.32.163.167 on 1 June 1957. Downloaded from THE NEPHROTIC SYNDROME IN EARLY INFANCY: A REPORT OF THREE CASES* BY H. McC. GILES, R. C. B. PUGH, E. M. DARMADY, FAY STRANACK and L. I. WOOLF From the Department of Paediatrics, St. Mary's Hospital, The Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, and the Central Laboratory, Portsmouth (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION, DECEMBER 12, 1956) The nephrotic syndrome is characterized by evidence of genetic aetiology inasmuch as two of generalized oedema, hypoproteinaemia with diminu- the infants were brother and sister and both sets of tion or reversal of the albumin/globulin ratio, hyper- parents were cousins. Further points of interest lipaemia and gross albuminuria. Haematuria is not were the demonstration of anisotropic crystalline prominent; hypertension and azotaemia, except in material in alcohol-fixed tissues from all three the terminal stages, are slight and transient and infants, and the discovery on renal microdissection often do not occur at all. Recognition of this of lesions of the proximal tubule recalling those syndrome presents no difficulty but in many cases, found in Fanconi-Lignac disease (cystinosis). particularly in childhood, its cause remains obscure. Occasionally certain drugs such as troxidone or mercury, or certain diseases such as amyloidosis, Case Reports pyelonephritis, diabetes, disseminated lupus erythe- The parents of the first two patients (and the paternal copyright. matosus or renal vein thrombosis, can be in- grandparents) are first cousins. They, and a sister born criminated. In cases which develop renal failure three years before the first of her affected siblings, have and come to necropsy the lesions of glomerulo- been investigated in detail and show no sign of renal II disease.