De-France, Pointe-À-Pitre, and London Carnivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weathering Process on Tropical Volcanics Islands (Guadeloupe

A696 Goldschmidt Conference Abstracts 2005 The Earth's Weathering Engine Weathering process on tropical Influence of overstory vegetation on volcanics islands (Guadeloupe, long-term chemical weathering rates 1 2 3 Martinique and Réunion) A.W. SCHROTH , A.J. FRIEDLAND AND B.C BOSTICK by using U-series 1Dept. of Earth Sciences/ Environmental Studies Program, 6182 Steele Hall, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, S. RAD, J. GAILLARDET, P. LOUVAT, 03755, USA ([email protected]) B. BOURDON AND C.J ALLEGRE 2Environmental Studies Program, Dartmouth College, IPGP, 4 place jussieu 75005 Paris, France Hanover NH, USA ([email protected]) ([email protected]) 3Dept. of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover NH, USA ([email protected]) The volcanic islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique and Réunion, are particuarly interesting for the study of landscape The influence of overstory vegetation on long-term base erosion. Their lithology is andesitic (Martinique, Guadeloupe) cation depletion rates in soil is significant in the context of to basaltic (Réunion). They are located in a tropical climate global climate cycles, soil health and forest management, and with high temperatures (24°C to 28°C), high precipitation, neutralization of acid deposition. Because other variables that sharp relief and very dense vegetation. These characteristics influence chemical weathering in natural systems are often not favour high weathering rates with significant variations, over a controlled (i.e. parent material composition, elevation, land- short distance, from one basin to another. use history), studies that isolate overstory effects on chemical We have taken samples from main streams of Guadeloupe, weathering are limited, particularly on timescales that would Martinique and Réunion (dissolved phase, particles and sand) be evident in the pedogenic record. -

Historical Archaeology in the French Caribbean: an Introduction to a Special Volume of the Journal of Caribbean Archaeology

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2004 ISSN 1524-4776 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE FRENCH CARIBBEAN: AN INTRODUCTION TO A SPECIAL VOLUME OF THE JOURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ARCHAEOLOGY Kenneth G. Kelly Department of Anthropology University of South Carolina Columbia SC 29208, USA [email protected] _______________________________________________________ The Caribbean region has seen a projects too numerous to mention, throughout tremendous growth in historical archaeology the Caribbean, with only a few areas excepted over the past 40 years. From important, (for an example of the coverage, see the although isolated beginnings in Jamaica, at papers in Farnsworth 2001 and Haviser 1999). Port Royal and Spanish Town and Montpelier (Mayes 1972; Mathewson 1972, 1973; Not only have nearly all islands of the Higman 1974, 1998), in Barbados at Newton Caribbean been the focus of at least some Cemetery (Handler and Lange 1978), and historical archaeology, but also the types of elsewhere in the Caribbean, the field has historical archaeological research have been expanded at a phenomenal rate. The late diverse. Thus, studies of both industry and 1970s and the early 1980s saw the initiation of labor have been conducted on sugar, coffee several important long-term studies, including and cotton plantations in the Greater and Norman Barka’s island-wide focus on rural Lesser Antilles. Military fortifications have and urban life in the Dutch territory of St. been documented and explored in many areas. Eustatius (Barka 1996), Kathleen Deagan’s Urban residential and commercial sites have multi-year project at Puerto Real and the been investigated, and ethnic minorities neighboring site of En Bas Saline in Haïti within the dominant class, such as Jewish and (Deagan 1995), Douglas Armstrong’s work at Irish populations, have been the focus of Drax Hall, Jamaica (Armstrong 1985, 1990), research programs. -

Critical Care Medicine in the French Territories in the Americas

01 Pan American Journal Opinion and analysis of Public Health 02 03 04 05 06 Critical care medicine in the French Territories in 07 08 the Americas: Current situation and prospects 09 10 11 1 2 1 1 1 Hatem Kallel , Dabor Resiere , Stéphanie Houcke , Didier Hommel , Jean Marc Pujo , 12 Frederic Martino3, Michel Carles3, and Hossein Mehdaoui2; Antilles-Guyane Association of 13 14 Critical Care Medicine 15 16 17 18 Suggested citation Kallel H, Resiere D, Houcke S, Hommel D, Pujo JM, Martino F, et al. Critical care medicine in the French Territories in the 19 Americas: current situation and prospects. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e46. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2021.46 20 21 22 23 ABSTRACT Hospitals in the French Territories in the Americas (FTA) work according to international and French stan- 24 dards. This paper aims to describe different aspects of critical care in the FTA. For this, we reviewed official 25 information about population size and intensive care unit (ICU) bed capacity in the FTA and literature on FTA ICU specificities. Persons living in or visiting the FTA are exposed to specific risks, mainly severe road traffic 26 injuries, envenoming, stab or ballistic wounds, and emergent tropical infectious diseases. These diseases may 27 require specific knowledge and critical care management. However, there are not enough ICU beds in the FTA. 28 Indeed, there are 7.2 ICU beds/100 000 population in Guadeloupe, 7.2 in Martinique, and 4.5 in French Gui- 29 ana. In addition, seriously ill patients in remote areas regularly have to be transferred, most often by helicopter, 30 resulting in a delay in admission to intensive care. -

The Dougla Poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad

The dougla poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy Centre of Ethnicity and Racism Studies June 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © The University of Leeds, 2014, Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Shirley Anne Tate. Her refreshing serenity and indefatigable spirit often helped combat my nerves. I attribute my on-going interest in learning about new approaches to race, sexuality and gender solely to her. All the ideas in this research came to fruition in my supervision meetings during my master’s degree. Not only has she expanded my intellectual horizons in a multitude of ways, her brilliance and graciousness is simply unsurpassed. There are no words to express my thanks to Dr Robert Vanderbeck for his guidance. He not only steered along the project to completion but his meticulous editing made this more readable and deserves a very special recognition for his patience, understanding, intelligence and sensitive way of commenting on my work. I would like to honour and thank all of my family. My father who was my refuge against many personal storms and who despite facing so many of his own battles, never gave up on mine. -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Music, Mas, and the Film and Video Segments

Entertainment Services with Special Reference to MUSIC, MAS, AND THE FILM AND VIDEO SEGMENTS Submitted to: MR. HENRY S. GILL Communications Director/Team Leader CARICOM Trade Project Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery (RNM) "Windmark", First Avenue, Harts Gap Hastings, Christ Church Barbados Submitted by: MS. ALLISON DEMAS AND DR. RALPH HENRY December 2001 Entertainment Services with Special Reference to Music, Mas, and the Film & Video Segments i Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................VI SECTION I 1.0 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives of Study........................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Delimitations and Limitations....................................................................................... 2 1.3 Outline of Study............................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Intellectual Property Rights.......................................................................................... 4 1.5 Industrial Organisation ................................................................................................ 7 1.6 Music........................................................................................................................... 11 1.7 Street Festivals........................................................................................................... -

Cultural Maintenance and the Politics of Fulfillment in Barbados’S Junior Calypso Monarch Programme

MASK AND MIRROR: CULTURAL MAINTENANCE AND THE POLITICS OF FULFILLMENT IN BARBADOS’S JUNIOR CALYPSO MONARCH PROGRAMME A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC MAY 2016 By Anjelica Corbett Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, chairperson Ricardo Trimillos Njoroge Njoroge Keywords: Anjelica Corbett, Calypso, Carnival, Nationalism, Youth Culture, Barbados Copyright © 2016 Anjelica Corbett Acknowledgements Foremost, I would like to thank God because without him nothing would be possible. I would also like to thank the National Cultural Foundation, the Junior Calypso Monarch Programme participants, Chrystal Cummins-Beckles, and Ian Webster for welcoming into the world of Bajan calypso and answering my questions about this new environment. My gratitude also extends to the Junior Calypso Monarch Programme participants for allowing me to observe and their rehearsals and performances and sharing their love of calypso with me. I would like to thank Dr. Frederick Lau, Dr. Byong-Won Lee, Dr. Ricardo Trimillos, and Dr. Njoroge Njoroge, and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa's Music Department for approving this project and teaching me valuable lessons throughout this process. I would especially like to thank my fellow colleagues in the Ethnomusicology department for their emotional and academic support. Finally, I would like to thank my family for support and encouragement throughout my academic career. i Abstract Barbados, like other Caribbean nations, holds junior calypso competitions for Barbadian youth. These competitions, sponsored by Barbados’s National Cultural Foundation (NCF), allow the youth to express their opinions on society. -

One Dead, Roofs Off and Flooding in Trinidad, Grenada

FREE www.caribbeanlifenews.com QUEENS/LONG ISLAND/BRONX/MANHATTAN June 23–29, 2017 BRET BRINGS MISERY One dead, roofs off and Youth designer honored flooding in Trinidad, Grenada Nine-year-old Sappire Autumn Rose is presented with the Golden Arrowhead of Achievement Youth Award by Barbara Atherly, consul general of Guyana to New York. See story on Page 3. By Bert Wilkinson relieved Prime Minister Keith Photo by Tangerine Clarke Grenada and its smaller fam- Rowley who is already trying to ily islands as well as the Dutch steer the oil and gas-rich twin dependencies of Aruba, Bonaire island republic with Tobago and Curacao were spared the back to economic prosperity Give Caribbean ‘Dreamers’ permanent status: Clarke wrath of Tropical Storm Bret after years of poor governance as it roared through the Car- decisions and shocks from rel- By Nelson A. King into the fabric of this nation,” administration Thursday ibbean and northern South atively low oil and gas prices. As the United States said Congresswoman Yvette D. night, President Trump will American countries this week, “This was a serious storm Deferred Actions for Childhood Clarke, the daughter of Jamai- not immediately eliminate dumping tons of rain, snarling but everything was in place Arrivals (DACA) program, oth- can immigrants. protections for the so-called traffic, cancelling commercial and I just want to thank every- erwise known as the “Dream “But the DACA program “Dreamers,” undocumented flights and closing govern- body who did everything that Program”, marks its fifth remains under threat,” Clarke, immigrants who came to the ment and private sector offices they were supposed to do. -

Jazz, Race, and Gender in Interwar Paris

1 CROSSING THE POND: JAZZ, RACE, AND GENDER IN INTERWAR PARIS A dissertation presented by Rachel Anne Gillett to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts May, 2010 2 CROSSING THE POND: JAZZ, RACE, AND GENDER IN INTERWAR PARIS by Rachel Anne Gillett Between 1920 and 1939 the nightclubs of Montmartre became a venue where different nationalities came into contact, danced, talked, and took advantage of the freedom to cross the color line that Paris and the ―color-blind‖ French audience seemed to offer. The fascination for black performers known as the tumulte noir provided the occasion for hundreds of jazz and blues performers to migrate to Paris in these years. French society was inundated with the sounds of jazz and also with images and stereotypes of jazz performers that often contained primitivist, exotic and sexualized associations. The popularity of jazz and its characterization as ―black‖ music raised the question of how the French state dealt with racial difference. It caused consternation among „non- jazz‟ black men and women throughout the Francophone Atlantic many of whom were engaged in constructing an intellectual pan-Africanist discourse with a view to achieving full citizenship and respect for French colonial subjects. This manuscript examines the tension between French ideals of equality, and „color-blindness,‟ and the actual experiences of black men and women in Paris between the wars. Although officially operating within the framework of a color-blind Republican model, France has faced acute dilemmas about how to deal with racial and ethnic differences that continue to spark debate and controversy. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

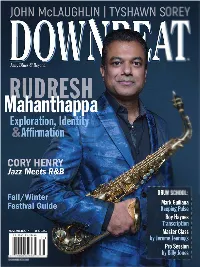

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana ABSTRACTS & PROGRAM NOTES updated October 30, 2015 Abeles, Harold see Ondracek-Peterson, Emily (The End of the Conservatory) Abeles, Harold see Jones, Robert (Sustainability and Academic Citizenship: Collegiality, Collaboration, and Community Engagement) Adams, Greg see Graf, Sharon (Curriculum Reform for Undergraduate Music Major: On the Implementation of CMS Task Force Recommendations) Arnone, Francesca M. see Hudson, Terry Lynn (A Persistent Calling: The Musical Contributions of Mélanie Bonis and Amy Beach) Bailey, John R. see Demsey, Karen (The Search for Musical Identity: Actively Developing Individuality in Undergraduate Performance Students) Baldoria, Charisse The Fusion of Gong and Piano in the Music of Ramon Pagayon Santos Recipient of the National Artist Award, Ramón Pagayon Santos is an icon in Southeast Asian ethnomusicological scholarship and composition. His compositions are conceived within the frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions and feature western and non- western elements, including Philippine indigenous instruments, Javanese gamelan, and the occasional use of western instruments such as the piano. Receiving part of his education in the United States and Germany (M.M from Indiana University, Ph. D. from SUNY Buffalo, studies in atonality and serialism in Darmstadt), his compositional style developed towards the avant-garde and the use of extended techniques. Upon his return to the Philippines, however, he experienced a profound personal and artistic conflict as he recognized the disparity between his contemporary western artistic values and those of postcolonial Southeast Asia. Seeking a spiritual reorientation, he immersed himself in the musics and cultures of Asia, doing fieldwork all over the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, resulting in an enormous body of work.