CRM Vol. 21, No. 7 (1998)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westray Story a Predictable Path to Disaster

3 . // ^V7 / C‘H- The Westray Story A Predictable Path to Disaster Report of the Westray Mine Public Inquiry Justice K. Peter Richard, Commissioner Volume One November 1997 LIBRARY DEPARTfvtEr,T Or NATURAL RESOURCES. \ HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA \ ^V 2,2,4- VJ. I Published on the authority of the Lieutenant Governor in Council c, by the Westray Mine Public Inquiry. © Province of Nova Scotia 1997 ISBN 0-88871-465-3 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Westray Mine Public Inquiry (N.S.) The Westray story: a predictable path to disaster Includes bibliographical references. Partial contents: v.[3] Reference - v.[4] Executive summary. ISBN 0-88871-465-3 (v.l) - 0-88871-466-1 (v.2) - 0-88871-467-X ([v.3])-0-88871-468-8 ([v.4]) 1. Westray Mine Disaster, Plymouth, Pictou, N.S., 1992. 2. Coal mine accidents—Nova Scotia—Plymouth (Pictou Co.) I. Richard, K. Peter, 1932- II. Title. TN806C22N6 1997 363.11’9622334'0971613 C97-966011-4 Cover: Sketch of Westray mine by Elizabeth Owen Permission is hereby given by the copyright holder for any person to reproduce this report or any part thereof. “The most important thing to come out of a mine is the miner.” Frederic Le Play (1806-1882) French sociologist and inspector general of mines of France » At 5:20 am on 9 May 1992 the Westray mine exploded taking the lives of the following 26 miners. John Thomas Bates, 56 Trevor Martin Jahn, 36 Larry Arthur Bell, 25 Laurence Elwyn James, 34 Bennie Joseph Benoit, 42 Eugene W. Johnson, 33 Wayne Michael Conway, 38 Stephen Paul Lilley, 40 Ferris Todd Dewan, 35 Michael Frederick MacKay, 38 Adonis J. -

Let's Talk Turkey

Let’s Talk Turkey The Official Newsletter of the Town of East Granby September 2017 • Volume XXII, Issue VI Autumn, A Colorful Time of Year As we get into the month of October, the forests and mountains will be alive with color, but you don’t have to drive out of town to appreciate the season. We in East Granby are fortunate to have beautiful natural amenities such as the Greenway, East Granby Farms, Granbrook and Cowles Parks, along with the Metacomet Trail within town borders! State Budget Update: Unfortunately, as I write this, we do not have a state budget. Hopefully when this edition of Let’s Talk Turkey reaches your doorstep, the legislature and the Governor will have figured things out and passed a balanced budget. Recent press reports of budget negotiations indicate that, while state revenue for East Granby will be lower than we received last year, it may not be reduced as drastically as in the Governor’s August budget. It’s Happening Right Here in East Granby: October is always a busy month with a lot of worthwhile activities in town such as the 17th Annual Empty Bowls Fundraiser to be held October 21st, Soccer Under the Lights at the High School on October 27th, and the Old Newgate Prison Halloween on Newsletter October 27th and 28th. For more information, please see the articles within this edition. Thanks to all our volunteers who make East Granby a great place to live! Publication Schedule September is Emergency Preparedness Month: Every year, as the evenings get crisp and winter is almost upon us, I provide preparedness tips and reminders for residents. -

Of Gold and Gravel: a Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek

OF GOLD AND GRAVEL A Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, 1934–1938 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan OF GOLD AND GRAVEL A Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, 1934–1938 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Edited and Notes by Chris Allan 2021 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Lynn Johnson, the granddaughter of Walter Johnson who designed the Coal Creek and Woodchooper Creek dredges; Rachel Cohen of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives; and Jeff Rasic, Adam Freeburg, Kris Fister, Brian Renninger, and Lynn Horvath who all helped with editing and photograph selection. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service Fairbanks Administrative Center 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska Front Cover: View from the pilot house of the Coal Creek gold dredge showing the bucket line carrying gravel to be processed inside the machine. The bucket line could dig up to twenty-two feet below the surface. University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska & Polar Regions Collections and Archives, Stanton Patty Family Papers. Title Page Inset: A stock certificate for Gold Placers, Inc. signed by General Manager Ernest N. Patty, November 16, 1935. University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska & Polar Regions Collections and Archives, Stanton Patty Family Papers. Back Cover: Left to right: The mail carrier Adolph “Ed” Biederman, his son Charlie, daughter Doris, the trapper and miner George Beck, Ed’s son Horace, and Jack Welch, the proprietor of Woodchopper Roadhouse. The group is at Slaven’s Roadhouse on the banks of the Yukon River posing with a mammoth tusk recovered from a placer mining tunnel. -

Connecticut Project Helper

Connecticut Project Helper Resources for Creating a Great Connecticut Project From the Connecticut Colonial Robin and ConneCT Kids! Connecticut State Symbols Famous Connecticut People Connecticut Information and Facts Famous Connecticut Places Connecticut Outline Map Do-it-Yourself Connecticut Flag Six Connecticut Project Ideas Connecticut Postcard and more…. www.kids.ct.gov What Makes a Great Connecticut Project? You! You and your ability to show how much you have learned about Connecticut. So, the most important part of your project will not be found in this booklet. But, we can help to give you ideas, resources, facts, and information that would be hard for you to find. Some students are good at drawing and art, some students are good at writing reports, and some students are good at crafts and other skills. But that part of the project will be only the beginning. A great Connecticut Project will be the one where you have become a Connecticut expert to the best of your abilities. Every State in the United States has a special character that comes from a unique blend of land, people, climate, location, history, industry, government, economy and culture. A great Connecticut Project will be the one where you can answer the question: "What makes Connecticut special?" In addition to this booklet, you should look for Connecticut information in your school library or town library. There are many online resources that can be found by doing internet searches. The more you find, the easier it will be to put together that Great Connecticut Project! The Connecticut Project Helper is produced and distributed by The ConneCT Kids Committee, and is intended for educational purposes only. -

GEOLOGY THEME STUDY Page 1

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS Dr. Harry A. Butowsky GEOLOGY THEME STUDY Page 1 Geology National Historic Landmark Theme Study (Draft 1990) Introduction by Dr. Harry A. Butowsky Historian, History Division National Park Service, Washington, DC The Geology National Historic Landmark Theme Study represents the second phase of the National Park Service's thematic study of the history of American science. Phase one of this study, Astronomy and Astrophysics: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study was completed in l989. Subsequent phases of the science theme study will include the disciplines of biology, chemistry, mathematics, physics and other related sciences. The Science Theme Study is being completed by the National Historic Landmarks Survey of the National Park Service in compliance with the requirements of the Historic Sites Act of l935. The Historic Sites Act established "a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the American people." Under the terms of the Act, the service is required to survey, study, protect, preserve, maintain, or operate nationally significant historic buildings, sites & objects. The National Historic Landmarks Survey of the National Park Service is charged with the responsibility of identifying America's nationally significant historic property. The survey meets this obligation through a comprehensive process involving thematic study of the facets of American History. In recent years, the survey has completed National Historic Landmark theme studies on topics as diverse as the American space program, World War II in the Pacific, the US Constitution, recreation in the United States and architecture in the National Parks. -

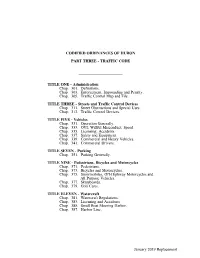

I:\My Files\Huron\D-TRAFFIC.Wpd

CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF HURON PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration Chap. 301. Definitions. Chap. 303. Enforcement, Impounding and Penalty. Chap. 305. Traffic Control Map and File. TITLE THREE - Streets and Traffic Control Devices Chap. 311. Street Obstructions and Special Uses. Chap. 313. Traffic Control Devices. TITLE FIVE - Vehicles Chap. 331. Operation Generally. Chap. 333. OVI; Willful Misconduct; Speed. Chap. 335. Licensing; Accidents. Chap. 337. Safety and Equipment. Chap. 339. Commercial and Heavy Vehicles. Chap. 341. Commercial Drivers. TITLE SEVEN - Parking Chap. 351. Parking Generally. TITLE NINE - Pedestrians, Bicycles and Motorcycles Chap. 371. Pedestrians. Chap. 373. Bicycles and Motorcycles. Chap. 375. Snowmobiles, Off-Highway Motorcycles and All Purpose Vehicles. Chap. 377. Skateboards. Chap. 379. Golf Carts. TITLE ELEVEN - Watercraft Chap. 381. Watercraft Regulations. Chap. 383. Licensing and Accidents. Chap. 385. Small Boat Mooring Harbor. Chap. 387. Harbor Line. January 2019 Replacement 3 CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF HURON PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration Chap. 301. Definitions. Chap. 303. Enforcement, Impounding and Penalty. Chap. 305. Traffic Control Map and File. CHAPTER 301 Definitions 301.01 Meaning of words and phrases. 301.26 Private road or driveway. 301.02 Agricultural tractor. 301.27 Public safety vehicle. 301.03 Alley. 301.28 Railroad. 301.031 Beacon; hybrid beacon. 301.29 Railroad sign or signal. 301.04 Bicycle; motorized bicycle; 301.30 Railroad train. moped. 301.31 Residence district. 301.05 Bus. 301.32 Right of way. 301.06 Business district. 301.321 Road service vehicle. 301.07 Commercial tractor. 301.33 Roadway. 301.08 Controlled-access highway. 301.34 Safety zone. 301.09 Crosswalk. -

Miners, Managers, and Machines : Industrial Accidents And

Miners, managers, and machines : industrial accidents and occupational disease in the Butte underground, 1880-1920 by Brian Lee Shovers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Montana State University © Copyright by Brian Lee Shovers (1987) Abstract: Between 1880 and 1920 Butte, Montana achieved world-class mining status for its copper production. At the same time, thousands of men succumbed to industrial accidents and contracted occupational disease in the Butte underground, making Butte mining significantly more dangerous than other industrial occupations of that era. Three major factors affected working conditions and worker safety in Butte: new mining technologies, corporate management, and worker attitude. The introduction of new mining technologies and corporate mine ownership after 1900 combined to create a sometimes dangerous dynamic between the miner and the work place in Butte. While technological advances in hoisting, tramming, lighting and ventilation generally improved underground working conditions, other technological adaptations such as the machine drill, increased the hazard of respiratory disease. In the end, the operational efficiencies associated with the new technologies could not alleviate the difficult problems of managing and supervising a highly independent, transient, and often inexperienced work force. With the beginning of the twentieth century and the consolidation of most of the major Butte mines under the corporate entity of Amalgamated Copper Company (later the Anaconda Copper Mining Company), conflict between worker and management above ground increased. At issue were wages, conditions, and a corporate reluctance to accept responsibility for occupational hazards. The new atmosphere of mistrust between miners and their supervisors provoked a defiant attitude towards the work place by workers which increased the potential for industrial accidents. -

Milford Mine National Register Historic District, Crow Wing County, Minnesota

MILFORD MINE NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICT, CROW WING COUNTY, MINNESOTA CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC and 10,000 Lakes Archaeology, Inc. March 2015 PUBLIC VERSION MILFORD MINE NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICT, CROW WING COUNTY, MINNESOTA CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Evaluation Prepared for Crow Wing County Land Services 322 Laurel Street, Suite 12 Brainerd, MN 56401 Prepared by Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 Amanda Gronhovd, M.S., RPA 10,000 Lakes Archaeology, Inc. 220 9th Avenue South South St. Paul, MN 55075 THIS PROJECT WAS FUNDED IN PART BY THE ARTS AND CULTURAL HERITAGE FUND March 2015 PUBLIC VERSION MILFORD MINE NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICT CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT This publication was made possible in part by the people of Minnesota through a grant funded by an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. Any views, findings, opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the State of Minnesota, the Minnesota Historical Society, or the Minnesota Historic Resources Advisory Committee. MILFORD MINE NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICT CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT MILFORD MINE NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICT CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT They came mostly to fulfill dreams of a better life and were willing to work hard and long to achieve that – if not for themselves, at least for their children… ~ ~ ~ Among the miners there developed a closeness and camaraderie that transcended the differences in language, ethnic background, and religion. -

Mines of El Dorado County

by Doug Noble © 2002 Definitions Of Mining Terms:.........................................3 Burt Valley Mine............................................................13 Adams Gulch Mine........................................................4 Butler Pit........................................................................13 Agara Mine ...................................................................4 Calaveras Mine.............................................................13 Alabaster Cave Mine ....................................................4 Caledonia Mine..............................................................13 Alderson Mine...............................................................4 California-Bangor Slate Company Mine ........................13 Alhambra Mine..............................................................4 California Consolidated (Ibid, Tapioca) Mine.................13 Allen Dredge.................................................................5 California Jack Mine......................................................13 Alveoro Mine.................................................................5 California Slate Quarry .................................................14 Amelia Mine...................................................................5 Camelback (Voss) Mine................................................14 Argonaut Mine ..............................................................5 Carrie Hale Mine............................................................14 Badger Hill Mine -

Commissioner of Mines for The

TERRITORY OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF MINES Report of the Commissioner of Mines for the EPENNPUM ENDED DECEMBER 31, 1954 DEPARTMENT OF MINES STAFF ON DECEMBER. 31, 1954 Phil R. Holdsworth, Commissioner of Mines, Box 1391, Juneau January 10, 1955 James A. Williams, Associate Mining Engineer, Box 1391, Juneau Honorable B. Frank Heintzleman Tdartin W. Jasper, Associate Mining Engineer, Box 2139, Anchorage Governor of Alaska Juneau. Alaska Wiley D. Robinson, Associate Coal Mining Engineer, Box 2139, Anchorage Sir : Robert M. Saunders, Associate Mining Engineer, Box C, College I I have the honor to submit to you, and through you Arthur E. Glover, Assayer-Engineer, Box 1408, Ketchikan to the Twenty-second Session of the Territorial kegisla- I ture, in accordance with Section 47-3-1319, ACLA, 1949, Peter 0. Sandvik, Assayer-Engineer, Box 657, Norne the report of the Commissioner of Mines for the bien- William F. Attwood, Assayer-Engineer, Box @, College nium ended December 31, 1954. RoyPe C. Rowe, Assayes, Box 2139, Anchorage Respectfully submitted, Cathryn Mack, Administrative Assistant, Box 1391, Juneau PHIL R. HOLDSWORTH Jean Crosby, Stenographer-Clerk, Box 1391, Juneau Commissioner of Mines CONTENTS Page Letter of Transmittal .................................................................................. 3 The I>epartment of Mines ............................................................................. 7 Atlministrative and General Information ........................................ 7 Cooperation with Federal Agencies ................................................... -

Mining and Rock Construction Technology Desk Reference

Mining and Rock Construction Technology Desk Reference 77007TS-RUSTAN0-Book.indb007TS-RUSTAN0-Book.indb i 110/20/20100/20/2010 110:09:200:09:20 AAMM Mining and Rock Construction Technology Desk Reference Rock mechanics, drilling and blasting Including acronyms, symbols, units and related terms from other disciplines Compiled by a group of experts from the Fragblast Section at the International Society of Explosives Engineers ISEE, Atlas Copco AB and Sandvik AB Editor-in-Chief Agne Rustan, formerly Luleå University of Technology, Sweden Associate Editors Claude Cunningham, Consulting Mining Engineer, South Africa Prof. William Fourney, University of Maryland, USA Prof. K.R.Y. Simha, Indian Institute of Science, India Dr. Alex T. Spathis, Orica Mining Services, Australia Downloaded by [Visvesvaraya Technological University (VTU Consortium)] at 01:50 01 March 2016 77007TS-RUSTAN0-Book.indb007TS-RUSTAN0-Book.indb iiiiii 110/20/20100/20/2010 110:09:210:09:21 AAMM Cover Illustrations: Illustration, Front Cover: Extensive rock reinforcement using rock bolts in combination with wire mesh in the LKAB mine in Kiruna, Sweden. Shown is a Boltec LC rock bolting rig. Photograph: Rob Naylor, 2010. © Atlas Copco. Used with kind permission. Illustration, Back Cover: It shows the working stages of the Roofex monitor bolt. © Atlas Copco MAI GmbH. Used with kind permission. CRC Press/Balkema is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Taylor & Francis Group, London, UK Typeset by Vikatan Publishing Solutions (P) Ltd, Chennai, India Printed and bound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe (a CPI group Company), Chippenham,Wiltshire All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

679 Part 77—Mandatory Safety Standards, Surface

Mine Safety and Health Admin., Labor Pt. 77 § 75.1916 Operation of diesel-powered 77.203 Use of material or equipment over- equipment. head; safeguards. 77.204 Openings in surface installations; (a) Diesel-powered equipment shall safeguards. be operated at a speed that is con- 77.205 Travelways at surface installations. sistent with the type of equipment 77.206 Ladders; construction; installation being operated, roadway conditions, and maintenance. grades, clearances, visibility, and other 77.207 Illumination. traffic. 77.208 Storage of materials. 77.209 Surge and storage piles. (b) Operators of mobile diesel-pow- 77.210 Hoisting of materials. ered equipment shall maintain full 77.211 Draw-off tunnels; stockpiling and re- control of the equipment while it is in claiming operations; general. motion. 77.211–1 Continuous methane monitoring de- (c) Standardized traffic rules, includ- vice; installation and operation; auto- ing speed limits, signals and warning matic deenergization of electric equip- signs, shall be established at each mine ment. 77.212 Draw-off tunnel ventilation fans; in- and followed. stallation. (d) Except as required in normal min- 77.213 Draw-off tunnel escapeways. ing operations, mobile diesel-powered 77.214 Refuse piles; general. equipment shall not be idled. 77.215 Refuse piles, construction require- (e) Diesel-powered equipment shall ments. not be operated unattended. 77.215–1 Refuse piles; identification. 77.215–2 Refuse piles; reporting require- ments. PART 77—MANDATORY SAFETY 77.215–3 Refuse piles; certification. STANDARDS, SURFACE COAL 77.215–4 Refuse piles; abandonment. MINES AND SURFACE WORK 77.216 Water, sediment, or slurry impound- ments and impounding structures; gen- AREAS OF UNDERGROUND COAL eral.