Experiment 7: Conservation of Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

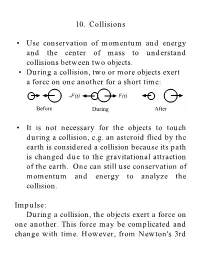

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Heat and Energy Conservation

1 Lecture notes in Fluid Dynamics (1.63J/2.01J) by Chiang C. Mei, MIT, Spring, 2007 CHAPTER 4. THERMAL EFFECTS IN FLUIDS 4-1-2energy.tex 4.1 Heat and energy conservation Recall the basic equations for a compressible fluid. Mass conservation requires that : ρt + ∇ · ρ~q = 0 (4.1.1) Momentum conservation requires that : = ρ (~qt + ~q∇ · ~q)= −∇p + ∇· τ +ρf~ (4.1.2) = where the viscous stress tensor τ has the components = ∂qi ∂qi ∂qk τ = τij = µ + + λ δij ij ∂xj ∂xi ! ∂xk There are 5 unknowns ρ, p, qi but only 4 equations. One more equation is needed. 4.1.1 Conservation of total energy Consider both mechanical ad thermal energy. Let e be the internal (thermal) energy per unit mass due to microscopic motion, and q2/2 be the kinetic energy per unit mass due to macroscopic motion. Conservation of energy requires D q2 ρ e + dV rate of incr. of energy in V (t) Dt ZZZV 2 ! = − Q~ · ~ndS rate of heat flux into V ZZS + ρf~ · ~qdV rate of work by body force ZZZV + Σ~ · ~qdS rate of work by surface force ZZX Use the kinematic transport theorm, the left hand side becomes D q2 ρ e + dV ZZZV Dt 2 ! 2 Using Gauss theorem the heat flux term becomes ∂Qi − QinidS = − dV ZZS ZZZV ∂xi The work done by surface stress becomes Σjqj dS = (σjini)qj dS ZZS ZZS ∂(σijqj) = (σijqj)ni dS = dV ZZS ZZZV ∂xi Now all terms are expressed as volume integrals over an arbitrary material volume, the following must be true at every point in space, 2 D q ∂Qi ∂(σijqi) ρ e + = − + ρfiqi + (4.1.3) Dt 2 ! ∂xi ∂xj As an alternative form, we differentiate the kinetic energy and get De -

Lecture 5: Magnetic Mirroring

!"#$%&'()%"*#%*+,-./-*+01.2(.*3+456789* !"#$%&"'()'*+,-".#'*/&&0&/-,' Dr. Peter T. Gallagher Astrophysics Research Group Trinity College Dublin :&2-;-)(*!"<-$2-"(=*%>*/-?"=)(*/%/="#* o Gyrating particle constitutes an electric current loop with a dipole moment: 1/2mv2 µ = " B o The dipole moment is conserved, i.e., is invariant. Called the first adiabatic invariant. ! o µ = constant even if B varies spatially or temporally. If B varies, then vperp varies to keep µ = constant => v|| also changes. o Gives rise to magnetic mirroring. Seen in planetary magnetospheres, magnetic bottles, coronal loops, etc. Bz o Right is geometry of mirror Br from Chen, Page 30. @-?"=)(*/2$$%$2"?* o Consider B-field pointed primarily in z-direction and whose magnitude varies in z- direction. If field is axisymmetric, B! = 0 and d/d! = 0. o This has cylindrical symmetry, so write B = Brrˆ + Bzzˆ o How does this configuration give rise to a force that can trap a charged particle? ! o Can obtain Br from " #B = 0 . In cylindrical polar coordinates: 1 " "Bz (rBr )+ = 0 r "r "z ! " "Bz => (rBr ) = #r "r "z o If " B z / " z is given at r = 0 and does not vary much with r, then r $Bz 1 2&$ Bz ) ! rBr = " #0 r dr % " r ( + $z 2 ' $z *r =0 ! 1 &$ Bz ) Br = " r( + (5.1) 2 ' $z *r =0 ! @-?"=)(*/2$$%$2"?* o Now have Br in terms of BZ, which we can use to find Lorentz force on particle. o The components of Lorentz force are: Fr = q(v" Bz # vzB" ) (1) F" = q(#vrBz + vzBr ) (2) (3) Fz = q(vrB" # v" Br ) (4) o As B! = 0, two terms vanish and terms (1) and (2) give rise to Larmor gyration. -

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24Th

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24th •Fluids – Static properties • Density and pressure • Hydrostatic equilibrium • Archimedes principle and buoyancy •Fluid Motion • The continuity equation • Bernoulli’s effect •Demonstration, iClicker and example problems Reading: pages 243 to 255 in text book (Chapter 15) Definitions: Density Pressure, ρ , is defined as force per unit area: Mass M ρ = = [Units – kg.m-3] Volume V Definition of mass – 1 kg is the mass of 1 liter (10-3 m3) of pure water. Therefore, density of water given by: Mass 1 kg 3 −3 ρH O = = 3 3 = 10 kg ⋅m 2 Volume 10− m Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Atmospheric pressure (1 atm.) is equal to 101325 N.m-2. 1 pound per square inch (1 psi) is equal to: 1 psi = 6944 Pa = 0.068 atm 1atm = 14.7 psi Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Pressure in Fluids Pressure, " p, is defined as force per unit area: # Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] " A8" rea A + $ In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static+ 8" fluid increases with depth. " – This allows an upward pressure force " to balance the downward gravitational force. + " $ – This condition is hydrostatic equilibrium. – Incompressible fluids like liquids have constant density; for them, pressure as a function of depth h is p p gh = 0+ρ p0 = pressure at surface " + Pressure in Fluids Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static fluid increases with depth. -

Fluid Dynamics and Mantle Convection

Subduction II Fundamentals of Mantle Dynamics Thorsten W Becker University of Southern California Short course at Universita di Roma TRE April 18 – 20, 2011 Rheology Elasticity vs. viscous deformation η = O (1021) Pa s = viscosity µ= O (1011) Pa = shear modulus = rigidity τ = η / µ = O(1010) sec = O(103) years = Maxwell time Elastic deformation In general: σ ε ij = Cijkl kl (in 3-D 81 degrees of freedom, in general 21 independent) For isotropic body this reduces to Hooke’s law: σ λε δ µε ij = kk ij + 2 ij λ µ ε ε ε ε with and Lame’s parameters, kk = 11 + 22 + 33 Taking shear components ( i ≠ j ) gives definition of rigidity: σ µε 12 = 2 12 Adding the normal components ( i=j ) for all i=1,2,3 gives: σ λ µ ε κε kk = (3 + 2 ) kk = 3 kk with κ = λ + 2µ/3 = bulk modulus Linear viscous deformation (1) Total stress field = static + dynamic part: σ = − δ +τ ij p ij ij Analogous to elasticity … General case: τ = ε ij C'ijkl kl Isotropic case: τ = λ ε δ + ηε ij ' kk ij 2 ij Linear viscous deformation (2) Split in isotropic and deviatoric part (latter causes deformation): 1 σ ' = σ − σ δ = σ + pδ ij ij 3 kk ij ij ij 1 ε' = ε − ε δ ij ij 3 kk ij which gives the following stress: σ = − δ + ςε δ + ηε 'ij ( p p) ij kk ij 2 'ij ε = With compressibility term assumed 0 (Stokes condition kk 0 ) 2 ( ς = λ ' + η = bulk viscosity) 3 τ Now τ = 2 η ε or η = ij ij ij ε 2 ij η = In general f (T,d, p, H2O) Non-linear (or non-Newtonian) deformation General stress-strain relation: ε = Aτ n n = 1 : Newtonian n > 1 : non-Newtonian n → ∞ : pseudo-brittle 1 −1 1−n 1 −1/ n (1−n) / n Effective viscosity η = A τ = A ε eff 2 2 Application: different viscosities under oceans with different absolute plate motion, anisotropic viscosities by means of superposition (Schmeling, 1987) Microphysical theory and observations Maximum strength of materials (1) ‘Strength’ is maximum stress that material can resist In principle, viscous fluid has zero strength. -

Conservation of Momentum

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 3 www.accessscience.com Conservation of momentum Contributed by: Paul W. Schmidt Publication year: 2014 The principle that, when a system of masses is subject only to forces that masses of the system exert on one another, the total vector momentum of the system is constant. Since vector momentum is conserved, in problems involving more than one dimension the component of momentum in any direction will remain constant. The principle of conservation of momentum holds generally and is applicable in all fields of physics. In particular, momentum is conserved even if the particles of a system exert forces on one another or if the total mechanical energy is not conserved. Use of the principle of conservation of momentum is fundamental in the solution of collision problems. See also: COLLISION (PHYSICS) . If a person standing on a well-lubricated cart steps forward, the cart moves backward. One can explain this result by momentum conservation, considering the system to consist of cart and human. If both person and cart are originally at rest, the momentum of the system is zero. If the person then acquires forward momentum by stepping forward, the cart must receive a backward momentum of equal magnitude in order for the system to retain a total momentum of zero. When the principle of conservation of momentum is applied, care must be taken that the system under consideration is really isolated. For example, when a rough rock rolls down a hill, the isolated system would have to consist of the rock plus the earth, and not the rock alone, since momentum exchanges between the rock and the earth cannot be neglected. -

Conservation of Energy Physics Lab VI

Conservation of Energy Physics Lab VI Objective This lab experiment explores the principle of energy conservation. You will analyze the ¯nal speed of an air track glider pulled along an air track by a mass hanger and string via a pulley falling unhindered to the ground. The analysis will be performed by calculating the ¯nal speed and taking measurements of the ¯nal speed. Equipment List Air track, air track glider with a double break 25mm flag, set of hanging masses, one photogate with Smart Timer, ruler, string, mass balance, meter stick Theoretical Background The conservation principles are the most powerful concepts to have been developed in physics. In this lab exercise one of these conservation principles, the conservation of energy, will be explored. This experiment explores properties of two types of mechanical energy, kinetic and potential energy. Kinetic energy is the energy of motion. Any moving object has kinetic energy. When an object undergoes translational motion (as opposed to rotational motion) the kinetic energy is, 1 K = Mv2: (1) 2 In this equation, K is the kinetic energy, M is the mass of the object, and v is the velocity of the object. Potential energy is dependent on the forces acting on an object of mass M. Forces that have a corresponding potential energy are known as conservative forces. If the force acting on the object is its weight due to gravity, then the potential energy is (since the force is constant), P = Mgh: (2) 2 Conservation of Energy In this equation, P is the potential energy, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and h is the distance above some reference position were the potential energy is set to zero. -

Distributed Generation: Glossary of Terms

Distributed Generation: Glossary of Terms Items with an asterisk (*) are terms as defined by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA collects, analyzes, and disseminates independent and impartial energy information to promote sound policymaking, efficient markets, and public understanding of energy and its interaction with the economy and the environment. Additional definitions are available online in EIA’s glossary of terms. Avoided Cost The incremental cost for a utility to produce one more unit of power. For example, because a qualifying facility (QF) as defined under the Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act or an Alternate Energy Production Facility and as defined in Iowa Code §476.42, reduces the utility’s need to produce this additional power themselves, the price utilities pay for QF power has been set to the avoided or marginal cost. Backfeed When electric power is being induced into the local power grid, power flows in the opposite direction from its usual flow. Backup Generator A generator that is used only for test purposes, or in the event of an emergency, such as a shortage of power needed to meet customer load requirements.* Backup Power Electric energy supplied by a utility to replace power and energy lost during an unscheduled equipment outage.* Baseload Generation (Baseload Plant) Generation from a plant, usually housing high-efficiency steam-electric units, which is normally operated to take all or part of the minimum load of a system, and which consequently produces electricity at an essentially constant rate and runs continuously. These units are operated to maximize system mechanical and thermal efficiency and minimize system operating costs.* Biomass Organic nonfossil material of biological origin constituting a renewable energy source.* Central Station Generation Production of energy at a large power plant and transmitted through infrastructure to a widely distributed group of users. -

7-7 Combining Energy and Momentum to Analyze Some Situations, We Apply Both Energy Conservation and Momentum Conservation in the Same Problem

Answer to Essential Question 7.6: A whole-vector approach, not splitting the velocity and momentum vectors into components, would also work (see End-of-Chapter Exercise 58). 7-7 Combining Energy and Momentum To analyze some situations, we apply both energy conservation and momentum conservation in the same problem. The trick is to know when to apply energy conservation (and when not to!) and when to apply momentum conservation. Consider the following Exploration. EXPLORATION 7.7 – Bringing the concepts together Two balls hang from strings of the same length. Ball A, with a mass of 4.0 kg, is swung back to a point 0.80 m above its equilibrium position. Ball A is released from rest and swings down and hits ball B. After the collision, ball A rebounds to a height of 0.20 m above its equilibrium position and ball B swings up to a height of 0.050 m. Let’s use g = 10 m/s2 to simplify the calculations. Step 1 – Sketch a diagram of the situation. This is shown in Figure 7.14. Step 2 – Our goal is to find the mass of ball B. Can we find the mass by setting the initial gravitational potential energy of ball A equal to the sum of the final potential energy of ball A and the final potential energy of ball B? Explain why or why not. The answer to the question is no. We can use energy conservation to help solve the problem, but setting the mechanical energy before the collision equal to the mechanical energy after the collision is assuming too much. -

A Formulation of Noether's Theorem for Fractional Problems Of

A Formulation of Noether’s Theorem for Fractional Problems of the Calculus of Variations∗ Gast˜ao S. F. Frederico Delfim F. M. Torres [email protected] [email protected] Department of Mathematics University of Aveiro 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal Abstract Fractional (or non-integer) differentiation is an important concept both from theoretical and applicational points of view. The study of problems of the calculus of variations with fractional derivatives is a rather recent subject, the main result being the fractional necessary optimality con- dition of Euler-Lagrange obtained in 2002. Here we use the notion of Euler-Lagrange fractional extremal to prove a Noether-type theorem. For that we propose a generalization of the classical concept of conservation law, introducing an appropriate fractional operator. Keywords: calculus of variations; fractional derivatives; Noether’s theo- rem. Mathematics Subject Classification 2000: 49K05; 26A33. 1 Introduction The notion of conservation law – first integral of the Euler-Lagrange equations – is well-known in Physics. One of the most important conservation laws is the arXiv:math/0701187v1 [math.OC] 6 Jan 2007 integral of energy, discovered by Leonhard Euler in 1744: when a Lagrangian L(q, q˙) corresponds to a system of conservative points, then −L(q, q˙)+ ∂2L(q, q˙) · q˙ ≡ constant (1) holds along all the solutions of the Euler-Lagrange equations (along the ex- tremals of the autonomous variational problem), where ∂2L(·, ·) denote the par- tial derivative of function L(·, ·) with respect to its second argument. Many other examples appear in modern physics: in classic, quantum, and optical ∗Research report CM06/I-04, University of Aveiro. -

Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy

This page intentionally left blank PLASMA PHYSICS AND FUSION ENERGY There has been an increase in worldwide interest in fusion research over the last decade due to the recognition that a large number of new, environmentally attractive, sustainable energy sources will be needed during the next century to meet the ever increasing demand for electrical energy. This has led to an international agreement to build a large, $4 billion, reactor-scale device known as the “International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor” (ITER). Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy is based on a series of lecture notes from graduate courses in plasma physics and fusion energy at MIT. It begins with an overview of world energy needs, current methods of energy generation, and the potential role that fusion may play in the future. It covers energy issues such as fusion power production, power balance, and the design of a simple fusion reactor before discussing the basic plasma physics issues facing the development of fusion power – macroscopic equilibrium and stability, transport, and heating. This book will be of interest to graduate students and researchers in the field of applied physics and nuclear engineering. A large number of problems accumulated over two decades of teaching are included to aid understanding. Jeffrey P. Freidberg is a Professor and previous Head of the Nuclear Science and Engineering Department at MIT. He is also an Associate Director of the Plasma Science and Fusion Center, which is the main fusion research laboratory at MIT. PLASMA PHYSICS AND FUSION ENERGY Jeffrey P. Freidberg Massachusetts Institute of Technology CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521851077 © J.