Arxiv:2004.09254V1 [Math.HO] 20 Apr 2020 Srpoue Ntels Frfrne Eo.I Sa Expand an Is It Below

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Ehresmann Et Commentées

Charles Ehresmann œuvres complètes et commentées CATÉGORIES STRUCTURÉES ET QUOTIENTS PARTIE III - 1 commentée par Andrée CHARLES EHRESMANN AMIENS 1980 CHARLES EHRESMANN 19 Avril 1905 - 22 Septembre 1979 «... Le mathématicien est engagé dans la poursuite d'un rêve sans fin, mais la traduction de ce rêve en formules précises exige un effort extraordinaire. Chaque problème résolu pose de nouvelles questions de plus en plus nombreuses.Mais qui d'en• tre nous ne se surprend pas quelquefois à se poser la question dangereuse : a quoi bon tout cet effort? On a dit que les Mathéma- tiques sont «le bulldozer de la Physique ». Bien que personne ne puisse douter de l'efficacité des Mathématiques dans les appli• cations pratiques, je ne crois pas qu'un mathématicien voie dans cette efficacité la justification de ses efforts car le vrai but de son rêve perpétuel est de comprendre la structure de toute chose». Extrait du discours fait par Charles EHRESMANN en 1967, pour remercier l'Université de Bologna de l'avoir nommé Docteur Honoris Causa. Tous droits de traduction, reproduction et adaptation réservés pour tous pays LISTE DES PUBLICATIONS DE CHARLES EHRESMANN 1. TRAVAUX DE RECHERCHE. 1. Les invariants intégraux et la topologie de l'espace proj ectif réglé, C. R. A. S. Paris 194 ( 1932 ), 2004-2006. 2. Sur la topologie de certaines variétés algébriques, C.R.A.S. Paris 196 ( 1933 ), 152-154. 3- Un théorème relatif aux espaces localement proj ectifs et sa généralisa• tion, C. R. A. S. Paris 196 (1933), 1354- 1356. 4. Sur la topologie de certains espaces homogènes, Ann. -

The Works of Charles Ehresmann on Connections: from Cartan

********************************** BANACH CENTER PUBLICATIONS, VOLUME 76 INSTITUTE OF MATHEMATICS POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WARSZAWA 2007 THE WORKS OF CHARLES EHRESMANN ON CONNECTIONS: FROM CARTAN CONNECTIONS TO CONNECTIONS ON FIBRE BUNDLES CHARLES-MICHEL MARLE Institut de Math´ematiques, Universit´ePierre et Marie Curie, 4, place Jussieu, 75252 Paris c´edex 05, France E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Around 1923, Elie´ Cartan introduced affine connections on manifolds and defined the main related concepts: torsion, curvature, holonomy groups. He discussed applications of these concepts in Classical and Relativistic Mechanics; in particular he explained how parallel transport with respect to a connection can be related to the principle of inertia in Galilean Mechanics and, more generally, can be used to model the motion of a particle in a gravitational field. In subsequent papers, Elie´ Cartan extended these concepts for other types of connections on a manifold: Euclidean, Galilean and Minkowskian connections which can be considered as special types of affine connections, the group of affine transformations of the affine tangent space being replaced by a suitable subgroup; and more generally, conformal and projective connections, associated to a group which is no more a subgroup of the affine group. Around 1950, Charles Ehresmann introduced connections on a fibre bundle and, when the bundle has a Lie group as structure group, connection forms on the associated principal bundle, with values in the Lie algebra of the structure -

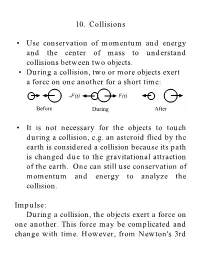

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

![Arxiv:1807.04136V2 [Math.AG] 25 Jul 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7341/arxiv-1807-04136v2-math-ag-25-jul-2018-177341.webp)

Arxiv:1807.04136V2 [Math.AG] 25 Jul 2018

HITCHIN CONNECTION ON THE VEECH CURVE SHEHRYAR SIKANDER Abstract. We give an expression for the pull back of the Hitchin connection from the moduli space of genus two curves to a ten-fold covering of a Teichm¨ullercurve discovered by Veech. We then give an expression, in terms of iterated integrals, for the monodromy representation of this connection. As a corollary we obtain quantum representations of infinitely many pseudo-Anosov elements in the genus two mapping class group. Contents 1. Introduction 2 1.1. Acknowledgements 6 2. Moduli spaces of vector bundles and Hitchin connection in genus two 6 2.1. The Heisenberg group 8 2.2. The Hitchin connection 10 2.2.1. Riemann surfaces with theta structure 11 2.2.2. Projectively flat connections 12 3. Teichm¨ullercurves and pseudo-Anosov mapping classes 16 3.1. Hitchin connection and Hyperlogarithms on the Veech curve 20 4. Generators of the (orbifold) fundamental group 25 4.1. Computing Monodromy 26 References 31 arXiv:1807.04136v2 [math.AG] 25 Jul 2018 This is author's thesis supported in part by the center of excellence grant 'Center for Quantum Geometry of Moduli Spaces' from the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF95). 1 HITCHIN CONNECTION ON THE VEECH CURVE 2 1. Introduction Let Sg be a closed connected and oriented surface of genus g ¥ 2, and consider its mapping class group Γg of orientation-preserving diffeomorphisms up to isotopy. More precisely, ` ` Γg :“ Diffeo pSgq{Diffeo0 pSgq; (1) ` where Diffeo pSgq is the group of orientation-preserving diffeomorphisms of Sg, and ` Diffeo0 pSgq denotes the connected component of the identity. -

Cartan Connections to Connections on fibre Bundles, and Some Modern Applications

The works of Charles Ehresmann on connections: from Cartan connections to connections on fibre bundles, and some modern applications Charles-Michel Marle Universite´ Pierre et Marie Curie Paris, France The works of Charles Ehresmann on connections: from Cartan connections to connections on fibre bundles, and some modern applications – p. 1/40 Élie Cartan’s affine connections (1) Around 1923, Élie Cartan [1, 2, 3] introduced the notion of an affine connection on a manifold. That notion was previously used, in a less general setting, by H. Weyl [16] and rests on the idea of parallel transport due to T. Levi-Civita [11]. The works of Charles Ehresmann on connections: from Cartan connections to connections on fibre bundles, and some modern applications – p. 2/40 Élie Cartan’s affine connections (1) Around 1923, Élie Cartan [1, 2, 3] introduced the notion of an affine connection on a manifold. That notion was previously used, in a less general setting, by H. Weyl [16] and rests on the idea of parallel transport due to T. Levi-Civita [11]. A large part of [1, 2] is devoted to applications of affine connections to Newtonian and Einsteinian Mechanics. Cartan show that the principle of inertia (which is at the foundations of Mechanics), according to which a material point particle, when no forces act on it, moves along a straight line with a constant velocity, can be expressed locally by the use of an affine connection. Under that form, that principle remains valid in (curved) Einsteinian space-times. The works of Charles Ehresmann on connections: from Cartan connections to connections on fibre bundles, and some modern applications – p. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences - - an Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics by C

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research Physics and Space Science Volume 12 Issue 4 Version 1.0 June 2012 Type : Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences - - An Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics By C. Y. Lo Applied and Pure Research Institute, Nashua, NH Abstract - The 2011 Shaw Prize in mathematical sciences is shared by Richard S. Hamilton and D. Christodoulou. However, the work of Christodoulou on general relativity is based on obscure errors that implicitly assumed essentially what is to be proved, and thus gives misleading results. The problem of Einstein’s equation was discovered by Gullstrand of the 1921 Nobel Committee. In 1955, Gullstrand is proven correct. The fundamental errors of Christodoulou were due to his failure to distinguish the difference between mathematics and physics. His subsequent errors in mathematics and physics were accepted since judgments were based not on scientific evidence as Galileo advocates, but on earlier incorrect speculations. Nevertheless, the Committee for the Nobel Prize in Physics was also misled as shown in their 1993 press release. Here, his errors are identified as related to accumulated mistakes in the field, and are illustrated with examples understandable at the undergraduate level. Another main problem is that many theorists failed to understand the principle of causality adequately. It is unprecedented to award a prize for mathematical errors. Keywords : Nobel Prize; general relativity; Einstein equation, Riemannian Space; the non- existence of dynamic solution; Galileo. GJSFR-A Classification : 04.20.-q, 04.20.Cv Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences -- An Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2012. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

1 INTRO Welcome to Biographies in Mathematics Brought to You From

INTRO Welcome to Biographies in Mathematics brought to you from the campus of the University of Texas El Paso by students in my history of math class. My name is Tuesday Johnson and I'll be your host on this tour of time and place to meet the people behind the math. EPISODE 1: EMMY NOETHER There were two women I first learned of when I started college in the fall of 1990: Hypatia of Alexandria and Emmy Noether. While Hypatia will be the topic of another episode, it was never a question that I would have Amalie Emmy Noether as my first topic of this podcast. Emmy was born in Erlangen, Germany, on March 23, 1882 to Max and Ida Noether. Her father Max came from a family of wholesale hardware dealers, a business his grandfather started in Bruchsal (brushal) in the early 1800s, and became known as a great mathematician studying algebraic geometry. Max was a professor of mathematics at the University of Erlangen as well as the Mathematics Institute in Erlangen (MIE). Her mother, Ida, was from the wealthy Kaufmann family of Cologne. Both of Emmy’s parents were Jewish, therefore, she too was Jewish. (Judiasm being passed down a matrilineal line.) Though Noether is not a traditional Jewish name, as I am told, it was taken by Elias Samuel, Max’s paternal grandfather when in 1809 the State of Baden made the Tolerance Edict, which required Jews to adopt Germanic names. Emmy was the oldest of four children and one of only two who survived childhood. -

Heat and Energy Conservation

1 Lecture notes in Fluid Dynamics (1.63J/2.01J) by Chiang C. Mei, MIT, Spring, 2007 CHAPTER 4. THERMAL EFFECTS IN FLUIDS 4-1-2energy.tex 4.1 Heat and energy conservation Recall the basic equations for a compressible fluid. Mass conservation requires that : ρt + ∇ · ρ~q = 0 (4.1.1) Momentum conservation requires that : = ρ (~qt + ~q∇ · ~q)= −∇p + ∇· τ +ρf~ (4.1.2) = where the viscous stress tensor τ has the components = ∂qi ∂qi ∂qk τ = τij = µ + + λ δij ij ∂xj ∂xi ! ∂xk There are 5 unknowns ρ, p, qi but only 4 equations. One more equation is needed. 4.1.1 Conservation of total energy Consider both mechanical ad thermal energy. Let e be the internal (thermal) energy per unit mass due to microscopic motion, and q2/2 be the kinetic energy per unit mass due to macroscopic motion. Conservation of energy requires D q2 ρ e + dV rate of incr. of energy in V (t) Dt ZZZV 2 ! = − Q~ · ~ndS rate of heat flux into V ZZS + ρf~ · ~qdV rate of work by body force ZZZV + Σ~ · ~qdS rate of work by surface force ZZX Use the kinematic transport theorm, the left hand side becomes D q2 ρ e + dV ZZZV Dt 2 ! 2 Using Gauss theorem the heat flux term becomes ∂Qi − QinidS = − dV ZZS ZZZV ∂xi The work done by surface stress becomes Σjqj dS = (σjini)qj dS ZZS ZZS ∂(σijqj) = (σijqj)ni dS = dV ZZS ZZZV ∂xi Now all terms are expressed as volume integrals over an arbitrary material volume, the following must be true at every point in space, 2 D q ∂Qi ∂(σijqi) ρ e + = − + ρfiqi + (4.1.3) Dt 2 ! ∂xi ∂xj As an alternative form, we differentiate the kinetic energy and get De -

Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician Clark Kimberling

Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician Clark Kimberling Mathematics Teacher, March 1982, Volume 84, Number 3, pp. 246–249. Mathematics Teacher is a publication of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). With more than 100,000 members, NCTM is the largest organization dedicated to the improvement of mathematics education and to the needs of teachers of mathematics. Founded in 1920 as a not-for-profit professional and educational association, NCTM has opened doors to vast sources of publications, products, and services to help teachers do a better job in the classroom. For more information on membership in the NCTM, call or write: NCTM Headquarters Office 1906 Association Drive Reston, Virginia 20191-9988 Phone: (703) 620-9840 Fax: (703) 476-2970 Internet: http://www.nctm.org E-mail: [email protected] Article reprinted with permission from Mathematics Teacher, copyright March 1982 by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. All rights reserved. mmy Noether was born over one hundred years ago in the German university town of Erlangen, where her father, Max Noether, was a professor of Emathematics. At that time it was very unusual for a woman to seek a university education. In fact, a leading historian of the day wrote that talk of “surrendering our universities to the invasion of women . is a shameful display of moral weakness.”1 At the University of Erlangen, the Academic Senate in 1898 declared that the admission of women students would “overthrow all academic order.”2 In spite of all this, Emmy Noether was able to attend lectures at Erlangen in 1900 and to matriculate there officially in 1904. -

Lecture 5: Magnetic Mirroring

!"#$%&'()%"*#%*+,-./-*+01.2(.*3+456789* !"#$%&"'()'*+,-".#'*/&&0&/-,' Dr. Peter T. Gallagher Astrophysics Research Group Trinity College Dublin :&2-;-)(*!"<-$2-"(=*%>*/-?"=)(*/%/="#* o Gyrating particle constitutes an electric current loop with a dipole moment: 1/2mv2 µ = " B o The dipole moment is conserved, i.e., is invariant. Called the first adiabatic invariant. ! o µ = constant even if B varies spatially or temporally. If B varies, then vperp varies to keep µ = constant => v|| also changes. o Gives rise to magnetic mirroring. Seen in planetary magnetospheres, magnetic bottles, coronal loops, etc. Bz o Right is geometry of mirror Br from Chen, Page 30. @-?"=)(*/2$$%$2"?* o Consider B-field pointed primarily in z-direction and whose magnitude varies in z- direction. If field is axisymmetric, B! = 0 and d/d! = 0. o This has cylindrical symmetry, so write B = Brrˆ + Bzzˆ o How does this configuration give rise to a force that can trap a charged particle? ! o Can obtain Br from " #B = 0 . In cylindrical polar coordinates: 1 " "Bz (rBr )+ = 0 r "r "z ! " "Bz => (rBr ) = #r "r "z o If " B z / " z is given at r = 0 and does not vary much with r, then r $Bz 1 2&$ Bz ) ! rBr = " #0 r dr % " r ( + $z 2 ' $z *r =0 ! 1 &$ Bz ) Br = " r( + (5.1) 2 ' $z *r =0 ! @-?"=)(*/2$$%$2"?* o Now have Br in terms of BZ, which we can use to find Lorentz force on particle. o The components of Lorentz force are: Fr = q(v" Bz # vzB" ) (1) F" = q(#vrBz + vzBr ) (2) (3) Fz = q(vrB" # v" Br ) (4) o As B! = 0, two terms vanish and terms (1) and (2) give rise to Larmor gyration.