Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Manual for Lake-Bound Species and Habitats of Lakes Prespa, Ohrid and Shkodra/Skadar

{MANLEY 2006 #1} Monitoring Manual for Lake-bound Species and Habitats of Lakes Prespa, Ohrid and Shkodra/Skadar Implementing the EU Nature Conservation Directives in South-Eastern Europe Published by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity at Lakes Prespa, Ohrid and Shkodra/Skadar (CSBL) Rruga Skenderbej Pallati 6, Ap.1/3 Tirana, Albania T ++355 42 25 8650 F ++355 42 251 792 www.giz.de As at May 2019 Prepared by Amphibia: Katarina Ljubisavljevic1, Enerit Sacdanaku2, Bogoljub Sterijovski3 Aves: Nela Dubak4, Stefan Ferger5, Tomaz Mihelic6, Mirjan Topi7, Danka Uzunova3, Bojan Zeković8 Mammalia: Mareike Brix5, Ninoslav Đurović4, Bledi Hoxha7, Hajdana Božović Ilić4, Milos Jovic9, Aleksandar Stojanov3, Aleksandër Trajçe7 Odonata: Despina Kitanova3, Bledar Pepa10 Habitats: Daniela Jovanovska11, Ajola Mesiti12 Plants: Slavica Đurišic4, Ajola Mesiti12, Slobodan Stijepovic4, Daniela Jovanovska11 GIZ CSBL Team Jelena Perunicic ([email protected]) Focal Point Biodiversity and National Coordinator for Montenegro Alkida Sini ([email protected]) National Coordinator for Albania Nikoleta Bogatinovska ([email protected]) National Coordinator for North Macedonia Edited by Stefan Ferger5, Mareike Brix5, Marija Vugdelic13, Sabrina Essel14, Ralf Peveling14 Reviewed by Ferdinand Bego15, Lefter Kashta15 Additional contributions provided by participants of the Training Workshop on Monitoring Methodologies of the Project -

Monitoring Methodology and Protocols for 20 Habitats, 20 Species and 20 Birds

1 Finnish Environment Institute SYKE, Finland Monitoring methodology and protocols for 20 habitats, 20 species and 20 birds Twinning Project MK 13 IPA EN 02 17 Strengthening the capacities for effective implementation of the acquis in the field of nature protection Report D 3.1. - 1. 7.11.2019 Funded by the European Union The Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, Department of Nature, Republic of North Macedonia Metsähallitus (Parks and Wildlife Finland), Finland The State Service for Protected Areas (SSPA), Lithuania 2 This project is funded by the European Union This document has been produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Twinning Project MK 13 IPA EN 02 17 and and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Summary 6 Overview 8 Establishment of Natura 2000 network and the process of site selection .............................................................. 9 Preparation of reference lists for the species and habitats ..................................................................................... 9 Needs for data .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Protocols for the monitoring of birds .................................................................................................................... -

An Insight Guide of Prespa Lakes Region Short Description of the Region

An Insight Guide of Prespa Lakes Region Short description of the region Located in the north-western corner of Greece at 850 metres above sea level and surrounded by mountains, the Prespa Lakes region is a natural park of great significance due to its biodiversity and endemic species. Prespa is a trans boundary park shared between Greece, Albania and FYR Macedonia. It only takes a few moments for the receptive visitor to see that they have arrived at a place with its own unique personality. Prespa is for those who love nature and outdoor activities all year round. This is a place to be appreciated with all the senses, as if it had been designed to draw us in, and remind us that we, too, are a part of nature. Prespa is a place where nature, art and history come together in and around the Mikri and Megali Prespa lakes; there are also villages with hospitable inhabitants, always worth a stop on the way to listen to their stories and the histories of the place. The lucky visitor might share in the activities of local people’s daily life, which are all closely connected to the seasons of the year. These activities have, to a large extent, shaped the life in Prespa. The three main traditional occupations in the region are agriculture, animal husbandry and fishing. There are a lot of paths, guiding you into the heart of nature; perhaps up into the high mountains, or to old abandoned villages, which little by little are being returned once more to nature’s embrace. -

Dr. Konstantinos Stergiou – Curriculum Vitae Dr

Dr. Konstantinos Stergiou – Curriculum vitae Dr. Konstantinos Stergiou Monastiriou Terma, 53100 Florina (Greece) +306974828298 [email protected] www.stergioukon.com Date of birth 13/06/1983 Education 13/04/2011–28/06/2017 Ph.D. in Pedagogy EQF level 8 University of Western Macedonia, School of Education, Florina (Greece) Ph.D. in Pedagody, with entitled dissertation: Investigating and evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of education, Grade 10 (A scale of 1 to 10 applies to the marks of each subject in the Hellenic Higher Education). 01/09/2016–16/11/2018 Master of Arts (M.A.) EQF level 7 Limerick Institute of Technology (LIT), Limerick, Ireland Youth Work with Games and Digital Media, First Class Honours 31/10/2007–02/06/2010 Master of Education (M.Ed.) EQF level 7 University of Western Macedonia, School of Education, Florina (Greece) Master of Education, focused on the use Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in education. Thesis on the field of Economics of Education entitled : Measuring the Efficiency of Primary Schools of the Prefecture of Florina using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). ECTS 120, Grade 8.56 (A scale of 1 to 10 applies to the marks of each subject in the Hellenic Higher Education). 05/08/2008–21/08/2008 Master’s Degree Programme - Developing Intercultural Competence EQF level 7 University of Helsinki, Helsinki (Finland) Master’s Degree Programme in Intercultural Encounters at the University of Helsinki's Renvall Institute. 6 ECTS, Grade 3 (A scale of 1 to 5 applies to the marks of each subject in the Finish Higher Education). 29/08/2005–14/01/2006 Undergraduate Erasmus Program Scholarship EQF level 6 Vaxjo University, Vaxjo (Sweden) Exchange program (Erasmus scholarship) between Vaxjo University, Sweden and Aristotle Page 1 / 12 University of Thessaloniki. -

On the Basis of Article 65 of the Law on Real Estate Cadastre („Official Gazette of Republic of Macedonia”, No

On the basis of article 65 of the Law on Real Estate Cadastre („Official Gazette of Republic of Macedonia”, no. 55/13), the Steering Board of the Agency for Real Estate Cadastre has enacted REGULATION FOR THE MANNER OF CHANGING THE BOUNDARIES OF THE CADASTRE MUNICIPALITIES AND FOR DETERMINING THE CADASTRE MUNICIPALITIES WHICH ARE MAINTAINED IN THE CENTER FOR REC SKOPJE AND THE SECTORS FOR REAL ESTATE CADASTRE IN REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Article 1 This Regulation hereby prescribes the manner of changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities, as well as the determining of the cadastre municipalities which are maintained in the Center for Real Estate Cadastre – Skopje and the Sectors for Real Estate Cadastre in Republic of Macedonia. Article 2 (1) For the purpose of changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities, the Government of Republic of Macedonia shall enact a decision. (2) The decision stipulated in paragraph (1) of this article shall be enacted by the Government of Republic of Macedonia at the proposal of the Agency for Real Estate Cadastre (hereinafter referred to as: „„the Agency„„). (3) The Agency is to submit the proposal stipulated in paragraph (2) of this article along with a geodetic report for survey of the boundary line, produced under ex officio procedure by experts employed at the Agency. Article 3 (1) The Agency is to submit a proposal decision for changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities in cases when, under a procedure of ex officio, it is identified that the actual condition/status of the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities is changed and does not comply with the boundaries drawn on the cadastre maps. -

“Notes and Studies of Prespa in the Branislav Rusic Archoves at The

“Notes and Studies of Prespa in the Branislav Rusiќ Archives at the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and the Arts” Branislav Rusiќ was a member of the first post-war generation of Macedonian ethnographers who set the groundwork for ethnographic studies of Macedonia. His family originated from the village of German in Lower Prespa, now in Aegean Macedonia. He was born in the village of Tomino in the Poreč region, he received his primary and secondary education in Prilep, Kruševac and in Bitola, and in 1937 received a degree in ethnography from Belgrade University. He received his doctorate from Zagreb University in 1951. From 1939 to 1946 he worked at the State Archives and at the Ethnographic museum in Belgrade. In 1946 he moved to the newly established university in Skopje, where he formed a group on Ethnology, which he lead until 1958. From 1958 to the end of his life in 1971 he was a professor of Ethnography in the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. He was concurrently in charge of the division on folk costumes at the Folklore Institute in Skopje. Rusiќ’s greatest contribution to the ethnographic study of Macedonia is undoubtedly his extensive field research of every part of the country, either alone early in his career, or on field studies with his students in later years. He began his field research as a student in 1934 as a student at Belgrade University. There is hardly a village in Macedonia that escaped a study by Rusiќ, though his most voluminous studies were concentrated mostly in the regions of Poreč, Železnik, Debarce, Struga, Ohrid, Prespa, Slavište, Pijanec, Delčevo, Osogovia and Capari. -

Misconceptions Regading Three Levels Of

ПРИЛОЗИ, Одделение за природно-математички и биотехнички науки, МАНУ, том 40, бр. 1, стр. 93–103 (2019) CONTRIBUTIONS, Section of Natural, Mathematical and Biotechnical Sciences, MASA, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 93–103 (2019) Received: November 26, 2018 ISSN 1857–9027 Accepted: February 11, 2019 e-ISSN 1857–9949 UDC: 634.11-244.42(497.7)"2013/2017 634.53-244.42(497.7)"2013/2017 DOI: 10.20903/csnmbs.masa.2019.40.1.133 Original scientific paper PHYTOPHTHORA CACTORUM (LEBERT & COHN) J. SCHRÖT AS CAUSAL AGENT OF DIEBACK OF CHESTNUT AND APPLE TREES IN MACEDONIA# Mihajlo Risteski1*, Stephen Woodward2, Marin Ježić3, Rade Rusevski4, Biljana Kuzmanovska4, Kiril Sotirovski1 1Faculty of Forestry, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia 2The Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Scotland 3Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Croatia 4Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Food, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia *e-mail: [email protected] From 2013–2017, 11 chestnut populations and 16 apple orchards/plantations in Macedonia were examined for health; soil, root and bark samples were collected from trees expressing symptoms regarded as Phytophthora specific. Using leaf baits of Prunus laurocerasus and selective V8 Agar (PARPNH), 19 pure Phytophthora sp. cultures were isolated and identified as P. cactorum by ITS sequencing. Sixteen isolates were from apple trees and 3 from chestnut trees. Phylogenetic analyses suggested slight distance between P. cactorum isolates originating from chestnut trees compared to those from apple orchards. Assessment of pathogenicity using chestnuts twigs showed no differences be- tween P. cactorum isolates from the two tree host species. -

"Shoot the Teacher!": Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle

"SHOOT THE TEACHER!" EDUCATION AND THE ROOTS OF THE MACEDONIAN STRUGGLE Julian Allan Brooks Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 1992 Bachelor of Education, University of British Columbia, 200 1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Julian Allan Brooks 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Julian Allan Brooks Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: "Shoot the Teacher!" Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle Examining Committee: Chair: Professor Mark Leier Professor of History Professor AndrC Gerolymatos Senior Supervisor Professor of History Professor Nadine Roth Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Professor John Iatrides External Examiner Professor of International Relations Southern Connecticut State University Date Approved: DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Landraces of Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Under Organic Agriculture in a Protected Area in Greece

2nd Scientific Conference within the framework of the 9th European Summer Academy on Organic Farming, Lednice na Moravě, Czech Republic, June 24 - 26, 2009 Prelimenary results on a comparative study evaluating landraces of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under organic agriculture in a protected area in Greece. Vakali, C.1, Papathanasiou, F.,2 Papadopoulos, I.2 and Tamoutsidis, E.2 Key words: local landraces, dry beans, organic growing conditions, yield characteristics, cooking time Abstract Organic farming requires cultivars or landraces that are specifically adapted to this low input cropping system. Six landraces of Greek common dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and one from the neighbouring Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) were evaluated for different agronomic and physicochemical characteristics under organic conditions in the National Park of the lake Prespes, on the borders of Greece, FYROM and Albania. Significant differences among landraces were found in yield characteristics such as yield plant-1, pod plant-1 and seeds pod-1 with two of the landraces performing the best. The cooking time was estimated by measuring seed hardness using a penetrometer. There was a considerable variation between the landraces tested with cooking times between 25-45 minutes. Some of the landraces could be a useful resource for the development of organic farming systems in this protected area. Introduction Organic farming is increasingly gaining interest in Greece with organic farmers especially in the North part of the country to have tripled in the past few years. However, the research on organically grown land is limited with organic farming relying on the improvements achieved by conventional methods. -

Creating Touristic Itinerary in the Region of Prespa Abstract

International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection Vol. 4, No. 7, 2016 ISSN 2309-0405 CREATING TOURISTIC ITINERARY IN THE REGION OF PRESPA M.Sc. Ema MUSLLI, PhD Candidate University of Tirana ABSTRACT The Prespa Region is located on the Balkan Peninsula, between the countries of Albania, Macedonia and Greece. It includes Greater Prespa Lake and the surrounding beach and meadow areas, designated agricultural use areas and the towns of Pustec, Resen and Prespes. This region is now a part of the Trans-Boundary Biosphere Reserve ‘Ohrid-Prespa Watershed. Greater and Lesser Prespa lakes plus Ohrid Lake are included in the UNESCO world Heritage Site. This area has been known historically for its diverse natural and cultural features. Prespa Region is currently covered by Prespa National Parks in Albania and Greece and Galichica and Pelisteri National Parks in Macedonia. The natural environment and the cultural heritage are a key element designated for the development of the region’s sustainable tourism. This study was enhanced via the Geographic Info System (GIS) digital presentation showing the opportunities for nature tourism in the Pustec and Resen commune. The article also includes two touristic itineraries that will help a better promotion of the tourism in the Prespa Region. Keywords: Touristic potential, cultural heritage, nature heritage, touristic itineraries. INTRODUCTION The Greater Prespa Watershed is located in the southeastern region of Albania and in the southwestern part of Macedonia, in the region of Korçë, commune of Pustec in the Albanian part, in the Resen commune in the Macedonian part and in the Prespe commune in Greece. -

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

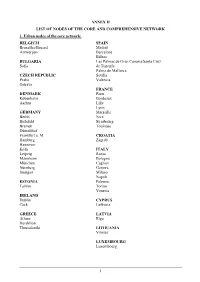

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

Management Plan

MANAGEMENT PLAN οf the River Basins of Western Macedonia River Basin District (GR09) Special Management Plan for the Sub-basin of Prespa in the River Basin Of Prespa (GR01) Summary JANUARY 2014 HELLENIC REPUBLIC MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE SPECIAL SECRETERIAT FOR WATER PROJECT: DEVELOPMENT OF THE RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLANS OF THE RIVER BASINS OF WEST MACEDONIA AND CENTRAL MACEDONIA RIVER BASIN DISTRICTS ACCORDING TO THE SPECIFICATIONS OF THE WFD 2000/60/EC, APPLYING THE GREEK LAW 3199/2003 AND THE GREEK PD 51/2007 CONSORTIUM: EXARCHOU NIKOLOPOULOS BENSASSON CONSULTING ENGINEERS SA - GEOSYNOLO LTD - LISA BENSASSON - ILIAS KOURKOULIS - ENVIROPLAN SA - DIKTIO SA - ECO CONSULTANTS SA - FOTEINI MPALTOGIANNI DEVELOPMENT OF THE RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF THE RIVER BASINS OF WEST MACEDONIA RIVER BASIN DISTRICT (GR09) Special Management Plan for the Sub-basin of Prespa in the River Basin Of Prespa (GR01) - SUMMARY G.G. of Management Plan’s Approval: G.G. B’ 181/31.1.2014 RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF THE RIVER BASINS OF WESTERN MACEDONIA RIVER BASIN DISTRICT Special Management Plan for the Sub-basin of Prespa in the River Basin of Prespa (GR01) Summary Index 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 2. OBJECTIVE AND CONTENTS OF THE SPECIAL RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN…3 3. CONSULTATION PROCESS…………………………………………………………………………………5 4. NATURAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE CHARACTERISTICS OF PRESPA SUB-BASIN……....7 5. COMPETENT AUTHORITIES……………………………………………………………………………..8 6. IDENTIFICATION OF WATER BODIES…………………………………………………………………9 6.1 Surface Water Bodies (SWB) ........................................................................................ 9 6.2 Groundwater bodies ...................................................................................................... 9 6.3 Heavily modified water bodies (HMWB) and Artificial water bodies (AWB) ............... 9 6.4 Protected Areas ........................................................................................................... 10 7.