The “Gryfice Scandal” in Poznań — Dealing with Abuses Committed in the Process of Establishing Cooperative Farms in the Poznań Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounds of War and Peace: Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945

10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. Exploiting to the full methodologies and research tools developed in the fields of sound and soundscape studies, the Sounds of War and Peace authors analyse their reflections on autobiographical texts and art. The studies demonstrate the role urban sounds played in the inhabitants’ forging a sense of 1945 Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945 identity as they adapted to new living conditions. The chapters also shed light on the ideological forces at work in the creation of urban sound space. Sounds of War and Peace. War Sounds of Soundscapes of European Cities in Volume 10 Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Renata Tańczuk is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Sławomir Wieczorek is a faculty member of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) · Wieczorek / Sławomir Tańczuk Renata ISBN 978-3-631-75336-1 EESM 10_275336_Wieczorek_SG_A5HC globalL.indd 1 16.04.18 14:11 10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. -

Oferty Pracy (Pdf, 667

POWIATOWY URZĄD PRACY W GRYFICACH 91 3842934; 91 3843506; www.pupgryfice.pl Dysponuje na dzień 24.09.2021 następującymi wolnymi miejscami pracy: STANOWISKO WYMAGANIA PRACODAWCY DANE PRACODAWCY REFUNDACJA WYNAGRODZENIA,NAGRÓD I SKŁADEK DLA OSÓB DO 30 ROKU ŻYCIA KIEROWCA SAMOCHODU WYMAGANE: PRAWO JAZDY GRYFICE CIĘZAROWEGO KAT. C+E KAT.C+E,ŚWIADECTWO WI-TRANS SP Z O O, SP.K KWALIFIKACJI,ORZECZENIE UL.LAZUROWA 5 LEKARSKIE I DAMIAN WIŚNIEWSKI PSYCHOLOGICZNE,KARTA KIEROWCY TEL.609 090 276 OFPR/19/1076 KELNER/KA WYMAGANE: DYSPOZYCYJNOŚĆ, NIECHORZE MILE WIDZIANE WYKSZTAŁCENIE RAWO TUR SP. Z O.O ŚREDNIE UL. BURSZTYNOWA 74 MARIUSZ RAKOWICZ TEL. 601-777-171 OFPR/21/0812 ROBOTY PUBLICZNE DRÓŻNIK WYMAGANE: GRYFICE OFERTA PRACY DLA OSÓB ZARZĄD DRÓG POWIATOWYCH ZAREJESTROWANYCH W PUP GRYFICE W RAMACH ROBÓT TEL. 91 384 21 13 PUBLICZNYCH- FUNDUSZ PRACY OFPR/21/0776 ROBOTNIK GOSPODARCZY WYMAGANE: GRYFICE OFERTA PRACY DLA OSÓB ZAKŁAD USŁUG KOMUNALNYCH ZAREJESTROWANYCH W PUP W GRYFICACH GRYFICE W RAMACH ROBÓT TEL. 91-38-420-47 PUBLICZNYCH- Rezerwa MRiPS- Program aktywizacji zawodowej OFPR/21/0801 bezrobotnych zamieszkujących na wsi MŁODSZY OPIEKUN WYMAGANE: WYKSZTAŁCENIE JAROMIN ŚREDNIE OGÓLNOKSZTAŁCĄCE DOM POMOCY SPOŁECZNEJ W OFERTA PRACY DLA OSÓB JAROMINIE ZAREJESTROWANYCH W PUP TEL: 913872529, 913873313 GRYFICE W RAMACH ROBÓT PUBLICZNYCH- Rezerwa MRiPS- Program aktywizacji zawodowej bezrobotnych zamieszkujących na OFPR/21/0804 wsi DOPOSAŻENIA STANOWISKA PRACY KONSERWATOR OŚRODKA WYMAGANE: REWAL 06.09.2021 DOMKI „GOŚCINIAK” 30.09.2021 OFERTA PRACY DLA OSÓB MAGDALENA GOŚCINIAK ZAREJESTROWANYCH W PUP UL. CZAPLI SIWEJ 7 GRYFICE W RAMACH TEL. 519-611-398 DOPOSAŻENIA STANOWISKA PRACY POWER 2021 OFPR/21/0773 1 MECHANIK POJAZDÓW WYMAGANE: DOŚWIADCZENIE MODLIMOWO 22.02.2021 30.12.2021 SAMOCHODOWYCH ZAWODOWE USŁUGOWY TRANSPORT ZAROBKOWY OFERTA PRACY DLA OSÓB MODLIMOWO 30 ZAREJESTROWANYCH W PUP PIOTR WAŃCOWICZ GRYFICE W RAMACH TEL. -

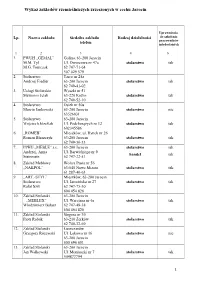

Wykaz Zakładów Rzemieślniczych Zrzeszonych W Cechu Jarocin

Wykaz zakładów rzemie ślniczych zrzeszonych w cechu Jarocin Uprawnienia Lp. Nazwa zakładu Siedziba zakładu Rodzaj działalno ści do szkolenia pracowników telefon młodocianych 1 2 3 4 6 1. PWUH „GEMAL” Golina, 63-200 Jarocin M.M. Tyl Ul. Dworcowa nr 47a stolarstwo tak M.G. Tomczak 62 747-71-64 507 029 579 2. Stolarstwo Tarce nr 25a Andrzej Fiedler 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-41-02 3. Usługi Stolarskie Wyszki nr 51 Sławomir Jelak 63-220 Kotlin stolarstwo tak 62 740-52-10 4. Stolarstwo Osiek nr 50a Marcin Jankowski 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo nie 63526031 5. Stolarstwo 63-200 Jarocin Wojciech Józefiak Ul. Podchor ąż ych nr 12 stolarstwo tak 602345586 6. „ROMEB” Mieszków, ul. Rynek nr 26 Roman Błaszczyk 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-30-33 7. PPHU „MEBLE” s.c. 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak Andrzej, Anna Ul. Barwickiego nr 9 handel tak Steinmetz 62 747-22-51 8. Zakład Meblowy Wolica Pusta nr 56 „NAKPOL” 63-040 Nowe Miasto stolarstwo tak 61 287-40-63 9. „ART.-STYL” Mieszków, 63-200 Jarocin Stolarstwo Ul. Jaroci ńska nr 27 stolarstwo tak Rafał Szik 62 747-75-50 604 454 826 10. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin „MEBLEX” Ul. Warciana nr 6a stolarstwo tak Włodzimierz Bałasz 62 747-48-38 604 454 826 11. Zakład Stolarski St ęgosz nr 30 Piotr Robak 63-210 Żerków stolarstwo tak 62 740-32-69 12. Zakład Stolarski Łuszczanów Grzegorz Ró żewski Ul. Ł ąkowa nr 16 stolarstwo nie 63-200 Jarocin 600 696 651 13. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin Jan Wałkowski Ul. -

Paradowska.Pdf

kunsttexte.de/ostblick 3/2019 - 1 Aleksandra !arado&ska Architecture and 0istor) and .heir $e resentations in German !ro aganda in the $eichsgau "artheland* Amongst the surviving traces of German urban lan- ce. Escutcheons to the left of the ma com rise sym- ning in !oland during "orld "ar ## eculiar artefacts bolic re resentations of the trades t) ical of the regi- ha en to be found. A large-scale ma of the $eichs- on. .hese include> soldiering% agriculture% crafts, in- gau "artheland is a case in oint%1 no& art of the dustry, science% joinery, and navigation. .he central collection of the 'tate Archive in (ydgoszc*% !oland section on the ma renders "arthegau in relation to +,ig. 1).2 .he ma belongs in a series of various illus- the ca itals of other rovinces: (erlin, "rocła& 4(res- trations, very much redolent of children’s rints and lau7% Kato&ice 4Katto&it*7% Krak@& 4Krakau7% 5Anigs- roviding synthetic re resentations of the territories berg% and Gdańsk 49anzig7. Escutcheons to the right annexed Germany or occupied b) it.3 As the style of bear the ne& coats of arms of the major cities in the the re resentation suggests, the ublisher, namely region: !o*naB 4!osen7% C@dD 4Lit*mannstadt7% #n- Heimatbund "artheland% intended the ma as an ac- o&rocła& 40ohensalza7% Kalisz 4Kalisch7% Gnie*no cessible means of circulating information on the 1the 4Gnesen7, and Włocła&ek [Leslau7. heartland of the German East3 4Kernland des deut- .he ex anse &ithin the outline of "arthegau fea- schen 6stens7. ,eatured in the framing% the lyrics of tures sim lified dra&ings &hich describe each of its Heinrich Gutberlet’s song 18arch of the Germans in arts. -

OBWIESZCZENIE Powiatowej Komisji Wyborczej W Jarocinie Z Dnia 2 Października 2018 R

OBWIESZCZENIE Powiatowej Komisji Wyborczej w Jarocinie z dnia 2 października 2018 r. o zarejestrowanych listach kandydatów na radnych w wyborach do Rady Powiatu Jarocińskiego zarządzonych na dzień 21 października 2018 r. Na podstawie art. 435 § 1 w związku z art. 450 ustawy z dnia 5 stycznia 2011 r. - Kodeks wyborczy (Dz. U. z 2018 r. poz. 754, 1000 i 1349) Powiatowa Komisja Wyborcza w Jarocinie podaje do wiadomości publicznej informację o zarejestrowanych listach kandydatów na radnych w wyborach do Rady Powiatu Jarocińskiego zarządzonych na dzień 21 października 2018 r. Okręg wyborczy Nr 1 Okręg wyborczy Nr 2 Okręg wyborczy Nr 3 Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL 1. KOŁODZIEJ Ryszard Idzi, lat 72, zam. Zakrzew 1. WŁODARCZYK Bronisława Kazimiera, lat 76, zam. 1. JĘDRASZCZYK Jacek Marek, lat 70, zam. Żerków 2. MATUSZAK Karol Piotr, lat 54, zam. Golina Jarocin 2. SZLACHETKA Andrzej, lat 34, zam. Komorze 3. IGNASIAK Katarzyna, lat 34, zam. Potarzyca 2. SZATKOWSKA Hanna Jadwiga, lat 51, zam. Jarocin Przybysławskie 4. PIECHOCKA Anita Magdalena, lat 34, zam. Cząszczew 3. FLORCZYK Wojciech Zdzisław, lat 66, zam. Jarocin 3. RYBACKA Agnieszka, lat 43, zam. Żerków 5. KOWNACKI Witold, lat 62, zam. Witaszyce 4. WALCZAK-GŁĄB Aleksandra, lat 60, zam. Jarocin 4. NOWAK Halina Maria, lat 64, zam. Szczonów 6. ORPEL Bartłomiej, lat 29, zam. Siedlemin 5. GROCHOWSKI Marek Jan, lat 66, zam. Jarocin 5. BIERNACIK Zbigniew, lat 49, zam. Chrzan 7. STASZAK Anna, lat 34, zam. Jarocin 6. FRANKIEWICZ Błażej, lat 54, zam. Jarocin 8. MĄKA Joanna, lat 23, zam. -

Newslettr.Iil;

5r-{f M6 /evq Poli sh Geneal ogical Soci ety of Mirncsota NEWSLETTr.Iil; VOLI-IME 7 SPRING 1999 NIMBER 1 Sources for Reconstructing a Polish Ancestral Vi[age: llm this ilssue q q q .Iank6 w Zale,6ry, Wielkopolska Sources for reconstructing a Polish ancestral village: Jank6w Zaleilny, Wielkopolska by Paul Theodore Kulas by Paul Ku1as........ page 1 President's Letter In his presentation, "Reconstructing the Vanished Communities by Greg Kishe1....... ...p.2 of Poland and Polish America" at the MGS "Branching Out" The Bulletin Board.... ....p. 3 conference in March, PGS-MN President illustrated a Greg Kishel Letters to the Editor: method of gathering information from various sources that allows Thanks amillion... one to gain an understanding of one's ancestral places of residence Lamczyk derivation in both Poland and in America.l I have used much the same method Rosen pioneers remembered.......p. 4 in reconstructing my ancestral villages in both Poland and in Family History research on-line wanting America. I have been to do articles about these villages for Tony Bukoski shon stories.........p. 5 quite sometime. Greg's presentation prompted me to gather together Reconstructing the vanished in this article the information that I have discovered over the years communities of Poland and about one of them--the village of origin in Poland of my Kulas Polish America ancestors: Janhdw Zaleflny, Wielhopolska.2 Besides describing my by Greg Kishe1....... ...p. 5 ancestral village, this article is intended to show what kinds of Looking for the Veleske family who information can be found in each source.3 It also is intended to give once lived at977 E. -

PDF (Angielski)

13 Analysis of Rescue Measures in Selected Industrial Plants Using Toxic Chemical Compounds in Poznań Tomasz Michalak, Jerzy Orłowski, Edyta Pędzieszczak-Michalak, Karol Marcinkowski University of Medical Sciences in Poznań Introduction The broad development of chemistry has been one of the crucial elements of the socio-economic development in the recent decades. It has contributed to an increased life expectancy and improved health condition of people to a large and unprecedented extent. However, it has also been realised that economic development poses substantial threats. Both on the global and local level, chemical substances can seriously and often irreversibly damage human health and natural environment. It has been demonstrated very clearly by huge chemical disasters, for example the Flixborough 30-tonne cyclohexan leakage and subsequent explosion in 1974, the Seveso dioxin release in 1976, the Bhopal methyl isocyanate release in 1984, the pollution of Rhine River after a fire in a chemical warehouse in Basilea in 1986 and the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster [1,3]. In Poznań the source of chemical threats to the inhabitants and environment are the plants using dangerous substances and road or rail transportation of dangerous commodities. A serious failure at a high- or increased-risk plant and during road or rail transportation of dangerous commodities may pose a threat to a very large group of people and to the environment (Table 1). In the recent years, there have been instances of mass chemical human poisoning in the city -

Lista Danych Dotyczących Terenu Site Check List

LISTA DANYCH DOTYCZĄCYCH TERENU SITE CHECK LIST Położenie Nazwa lokalizacji Zespół Pałacowo-Parkowy Location Site name Palace and Park Complex Miasto / Gmina Mielno, gmina Mieleszyn Town / Commune Mielno, Mieleszyn commune Powiat gnieźnieński District Gniezno county Województwo wielkopolskie Province (Voivodship) Wielkopolskie Province Powierzchnia Maksymalna dostępna powierzchnia (w jednym 4,51.08 ha nieruchomości kawałku) [ha] Area of property Max. area available (as one piece) [ha] 4,51.08 ha Kształt działki trapez The shape of the site trapezoid Możliwości powiększenia terenu (krótki opis) brak możliwości Possibility for expansion (short description) no possibilities Informacje Orientacyjna cena gruntu [PLN/m2] 1.946.550,00 zł - cena wywoławcza do dotyczące włączając 23% VAT przetargu nieruchomości Approx. land price [PLN/m2] PLN 1,946,550.00 - reserve price in tender Property including 23% VAT information Właściciel / właściciele Powiat Gnieźnieński Owner(s) Gniezno county Aktualny plan zagospodarowania Brak planu zagospodarowania przestrzennego (T/N) przestrzennego. Zgodnie ze Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego Gminy Mieleszyn, nieruchomość leży na terenie mieszanej zabudowy wiejskiej – M. Valid zoning plan (Y/N) No spatial development plan. Pursuant to the land use plan of the commune of Mieleszyn, the real estate is located in the area of the mixed rural development - M. Przeznaczenie w miejscowym planie brak planu zagospodarowania zagospodarowania przestrzennego przestrzennego Zoning no spatial development -

Acta Biologica 24/2017

Acta Biologica 24/2017 (dawne Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego Acta Biologica) Rada Redakcyjna / Editorial Board Vladimir Pésič (University of Montenegro) Andreas Martens (Karlsruhe University of Education) Stojmir Stojanovski (Hydrobiological Institute in Ohrid) Clémentine Fritsch (University of Antwerp) Leszek Jerzak (University of Zielona Góra) Barbara Płytycz (Jagiellonian University in Krakow) Maria Zając (Jagiellonian University in Krakow) Francesco Spada (University of Rome “La Sapienza”) Joana Abrantes (Universidade do Porto) Pedro J. Esteves (Universidade do Porto) Recenzenci / Reviewers Vladimir Pésič – University of Montenegro (Montenegro), Ralf Bastrop – University Rostock (Germany), Sergey Buga – Belarussian State University (Belarus), Oleksandr Puchkov – Institute of Zoology NAS (Ukraine), Zdeňka Svobodová – Czech Medical University (Czech Republic), Horst von Bannwarth – Universität zu Köln (Germany), Fedor Ciampor – Slovak Academy of Sciences (Slovakia), Giedre Visinskiene – Nature Research Centre (Lithuania), Jacek Międzobrodzki –Jagielonian University (Poland), Beata Krzewicka – Polish Academy of Sciences (Poland), Sead Hadziablahovic – Environmental Protection Agency (Montenegro), Robert Kościelniak – Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Krakowie (Poland), Katarzyna Wojdak-Maksymiec – West Pomeranian University of Technology Szczecin (Poland), Izabela Gutowska – West Pomeranian University of Technology Szczecin (Poland), Magdalena Moska – Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Poland) Redaktor naukowy -

Najciekawsze Wiejskie Zakątkiwielkopolski

Najciekawsze Wiejskie Zakątki Wielkopolski 2007-2015 r. / Most interesting RURAL AREAS of Wielkopolska 2007-2015 KATALOG OBIEKTÓW WYŁONIONYCH W KONKURSIE NA NAJLEPSZY OBIEKT TURYSTYKI NA OBSZARACH WIEJSKICH W WIELKOPOLSCE Nie musimy wyjeżdżać w odległe zakątki świata, żeby znaleźć miejsce z niepowtarzalnym klimatem. W wielkopolskich gospodarstwach agroturystycznych odnajdziemy wszystko to, co zagwarantuje doskonały wypoczynek i mnóstwo atrakcji. To właśnie w takich miejscach przekonamy się, czym jest prawdziwa, polska gościnność i tradycyjna kuchnia. Odwiedzając odrestaurowane dworki, czy folwarki poznamy również bogatą historię regionu. Wielkopolska wieś, to dzisiaj także miejsca odnowy biologicznej i niczym nieskrępowanej rekreacji na łonie natury, wśród lasów, jezior, rzek i to przez cały rok. Wielkopolska to także szlaki turystyczne wiodące wśród licznych zabytków architektury, zabytków przyrody, muzeów, stanowisk archeologicznych. Jak odnaleźć takie miejsca? Z pomocą przychodzi kolejna już Krzysztof Grabowski Wicemarszałek edycja Konkursu na najlepszy obiekt turystyki na obszarach Województwa Wielkopolskiego wiejskich w Wielkopolsce organizowanego od 2007 roku przez Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Wielkopolskiego, we współpracy z Uniwersytetem Przyrodniczym w Poznaniu i Wielkopolskim Towarzystwem Agroturystyki i Turystyki Wiejskiej. Wyłaniane są w nim najlepsze w swej branży gospodarstwa, które wcześniej przechodzą surową ocenę kapituły konkursowej. Są one oceniane w trzech kategoriach: gospodarstwo agroturystyczne w funkcjonującym -

Takk Dla Funduszy Norweskich I EOG

Takk dla Funduszy norweskich i EOG Fundusze norweskie i EOG 2009 – 2014 w Polsce Podsumowanie EEA and Norway Grants 2009 – 2014 in Poland Summary Wydawca: Publisher: Ministerstwo Rozwoju Ministry of Economic Development Departament Programów Pomocowych Department of Assistance Programmes Zdjęcia: Pictures: Łukasz Bera Łukasz Bera Jakub Swerpel Jakub Swerpel Fotografia foki pochodzi z archiwum Seal picture comes from the archive Słowińskiego Parku Narodowego of Słowiński National Park Egzemplarz bezpłatny Free copy Warszawa, październik 2017 Warsaw, October 2017 Fundusze norweskie i EOG 2009 – 2014 w Polsce EEA and Norway Grants 2009 – 2014 in Poland Szanowny Czytelniku, Dear Reader oddajemy w Twoje ręce podsumowanie drugiej edycji We present you the summary of the second edition of Funduszy norweskich i EOG, które z roku na rok coraz the EEA and Norway Grants that year after year change bardziej zmieniają otaczającą nas rzeczywistość. I choć the reality around us. And although the terms Norwegian nazwy: Norweski Mechanizm Finansowy oraz Mecha- Financial Mechanism and European Economic Area nizm Finansowy Europejskiego Obszaru Gospodarczego Financial Mechanism may sound a little mysterious, we brzmią tajemniczo, możemy zapewnić, że kryją się za nimi assure you that behind these, there are thousands of tysiące inspirujących ludzkich, pozytywnych historii. To inspiring human beings and uplifting stories. Successful zakończone sukcesem badania naukowe, natura, któ- scientific research, nature which beauty we can admire, rej piękno podziwiamy, uratowane zdrowie i życie wielu saved lives and good health of many Poles, trained Polek i Polaków, wyszkoleni oraz świadomi swoich praw employees aware of their rights and responsibilities. It is i obowiązków pracownicy. To przestrzeń, którą się ota- the space that surrounds us, monuments of culture you czasz, zabytki, które zwiedzasz i polecasz do zobaczenia explore and recommend for sightseeing to your family rodzinie i znajomym. -

Linguistic Geography and Historical Material. an Example of Inventory Ledgers from the Second Half of the 18Th Century Kept in Wielkopolska1

Gwary Dziś – vol. 13 – 2020, pp. 111–134 DOI 10.14746/gd.2020.13.5 ISSN 1898-9276 Błażej Osowski Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań Institute of Polish Philology ORCID: 0000-0002-4226-1378; e-mail: [email protected] Linguistic geography and historical material. An example of inventory ledgers from the second half of the 18th century kept in Wielkopolska1 Abstract: This work connects with the dialectological aspect of linguistic geography. The analysed material consists of inventory ledgers kept in Wielkopolska in the second half of the 18th century for nobility possessions. It is assumed that the then regional variety of the Polish language spoken in Wielkopolska was geographically diverse and this diversity was anything but accidental. It was affected by the education of the communication actors (including the writers) and their command of the literary Polish language, dialectal influences, impact of foreign languages, presence of archaic and innovative elements. This diversity is reflected in inventory ledgers; an analysis thereof was aimed at excerpting examples of lexical variants. This work contains 4 selected examples: ‘bogaty chłop’ [a wealthy farmer], ‘ziemniaki’ [potatoes], ‘mała izba’[a small room], ‘niebieski’ [blue]. Maps have been created for them. The analytical part is followed by generalisation of the variability in the surveyed sources (types of variability, its sources, levels, types of variants). Keywords: linguistic geography, historical dialectology, 18th century, inventory ledgers, variability, a linguistic map. Abstract: Geografia lingwistyczna a materiał historyczny. Na przykładzie wielkopolskich inwen - tarzy z drugiej połowy XVIII wieku. Niniejsza praca wpisuje się w nurt dialektologiczny geografii językowej. Analizowany materiał to wielkopolskie inwentarze dóbr szlacheckich z 2.