Christian Scriptures in Muslim Culture in the Work of Kenneth Cragg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews Reviewers in Tbls Issue the Rev

Book Reviews Reviewers In tbls Issue The Rev. H. J. Burgess, M.A., Ph.D. The Rev. Canon T. G. Mohan, M.A. The Rev. C. Sydney Carter, M.A., D.D. The Rev. J. A. Motyer, M.A., B.D. Madeleine Cowan The Rt. Rev. Stephen Neill, D.D. The Rev. Canon Kenneth Cragg, M.A., The Rev. James I. Packer, M.A., D.Phil. D.Phil. The Rev. Professor G. C. B. Davies, The Rev. Canon A. W. Parsons, L.Th. M.A.,D.D. Arthur Pollard, Esq., B.A., B.Litt. The Rev. Canon G. G. Dawson, D.D., The Rev. L. E. H. Stephens-Hodge, Ph.D. M.A. The Rev. A. J. K. Goss, M.A. The Rev. Alan M. Stibbs, M.A. The Rev. Douglas F. Horsefield The Rev. Denis H. Tongue, M.A. The Rt. Rev. Frank Houghton, B.A. The Rt. Rev. R. R. Williams, D.D., The Rev. Philip E. Hughes, M.A., B.D., Bishop of Leicester D.Litt. The Rev. M. A. P. Wood, D.S.C., M.A. Leslie T. Lyall, Esq., M.A. The Rev. Principal J. Stafford Wright, The Rev. A. V. M'Callin, B.A., B.D. M.A. The Rev. A. R. Milroy, M.A. CYRIL FORSTER GARBETT : ARCHBISHOP OF YoRK. By Charles Smyth. (Hodder and Stoughton.) 536pp. 35s. The life of Cyril Forster Garbett covers a period of years fraught with anxiety and danger both for Church and State. Between 1875 and 1955, the progress of science and discovery, the vast changes in social and economic life, the expansion and development of the Anglican Communion, not to mention the devastating intervention of two world wars, have all revolutionized the outlook of mankind. -

Rep.Ort Resumes

REP.ORT RESUMES ED 010 471 48 LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMSIN AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES. BY MOSES, LARRY OUR. OF INTELLIGENCE AND RESEARCH, WASHINGTON, 0.Ce REPORT NUMBER NDEA VI -34 PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICEMF40.27HC $7.08 177P. DESCRIPTORS *LANGUAGE PROGRAMS, *AREA STUDIES, *HIGHER EDUCATION, GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS, COURSES, *NATIONAL SURVEYS, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AFRICA, ASIA, LATIN AMERICA, NEAR EAST, WESTERN EUROPE, SOVIET UNION, EASTERN EUROPE . LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMS OFFERED IN 1964 BY UNITED STATES INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION ARE LISTEDFOR THE AREAS OF (1) AFRICA, (2) ASIA,(3) LATIN AMERICA, (4) NEAR EAST,(5) SOVIET UNION AND EASTERN EUROPE, AND (6) WESTERN EUROPE. INSTITUTIONS OFFERING BOTH GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS IN LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDIESARE ALPHABETIZED BY AREA CATEGORY, AND PROGRAM INFORMATIONON EACH INSTITUTION IS PRESENTED, INCLUDINGFACULTY, DEGREES OFFERED, REGIONAL FOCUS, LANGUAGE COURSES,AREA COURSES, LIBRARY FACILITIES, AND.UNIQUE PROGRAMFEATURES. (LP) -,...- r-4 U.,$. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION AND WELFARE I.: 3 4/ N- , . Office of Education Th,0 document has been. reproducedexactly as received from the petson or organization originating it. Pointsof View or opinions CD st4ted do not necessarily representofficial Office of EdUcirtion?' ri pdpition or policy. CD c.3 LANGUAGEAND AREA "Ai STUDYPROGRAMS IN AMERICAN VERSITIES EXTERNAL RESEARCHSTAFF DEPARTMENT OF STATE 1964 ti This directory was supported in part by contract withtheU.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. -

Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38)

M.L. Sehgal, International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 09 Issue 01, January 2019, Page 315-326 Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38) M. L. Sehgal (Fmrly: D. A. V. College, Jalandhar, Punjab (India)) Abstract: By 1917, Gandhi had become a front rung leader of I.N.C. Thereafter, the ‘Freedom Movement’ continued to swirl around him till 1947. During these years, there happened quite a number of political events which brought Gandhi and Iqbal on the opposite sides of the table. Our stress would , primarily, be discussing as to how Gandhi and Iqbal reacted on these political events which changed the psych of ‘British Indians’, in general, and the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent in particular.Nevertheless, a brief references would, also, be made to all these political events for the sake of continuity. Again, it would be in the fitness of the things to bear in mind that Iqbal entered national politics quite late and, sadly, left this world quite early(21 April 1938), i.e. over 9 years before the creation of Pakistan. In between, especially in the last two years, Iqbal had been keeping indifferent health. So, he might not have reacted on some political happenings where we would be fully entitled to give reactions of A.I.M.L. and I.N.C. KeyWords: South Africa, Eghbale Lahori, Minto-Morley Reform Act, Lucknow Pact, Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, Ottoman Empire, Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements, Simon Commission, Nehru Report, Communal Award, Round Table Conferences,. -

Introduction: Modern Arab-Islamic Scholarship on Ethics a Reflective Contextualization

Introduction: Modern Arab-Islamic Scholarship on Ethics A Reflective Contextualization Mohammed Hashas and Mutaz al-Khatib The question whether there are theories in Islamic ethics1 does not differ much from the similar question whether there is an Islamic philosophy.This issue was first raised by some 18th and 19th century European Orientalists—à la Johann Jakob Brucker (1696–1770), Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann (1761–1819), and Ern- est Renan (1823–1892) (ʿAbd al-Rāziq [1944] 2011, 8)—and has been revisited by a number of ongoing studies, particularly since the modern edition and public- ation of various manuscripts originally written in the classical period (before the 19th century) by various Muslim and non-Muslim scholars in and from different Islamic contexts—the Arabic, Persian, Ottoman, Indian and Malay contexts—where philosophy did not die out as a discipline, as the claim has gone for some good time (El-Rouayheb and Schmidtke 2017, 1–7). A review of classical Qurʾanic exegeses shows that neither the exegets have been concerned with building theories of ethics based on the Qurʾan (al-Khaṭīb 2017), nor have Muslim scholars in general, even though the sacred text is all about ethics (Rah- man 1982, 154–155). It was the challenge of modernity that required revisiting the Islamic tradition in search of Islamic philosophy, or Arab(ic) philosophy as some prefer to call it (Ṣalībā 1989, 9–11). The avant-guardist thinkers of the so-called Arab-Islamic nahḍa (awakening or renaissance) of the 19th century, like Rifaʿa Rafiʿ al-Tahtawi (1801–1873), Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838–1897) and Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905), did not deal with this question of ethics as contemporary scholars do. -

The Diocese of Egypt – History

THE DIOCESE OF EGYPT – HISTORY • The Bishops • History of the Diocese 1839-2000 • Early Evangelism 1898-1910 • The Cathedral on the Nile • The Cathedral in Zamalak • Early Hospital Pictures • Sketches 1895 – 1907 • Christianity in Egypt AD • BC Egypt and the Bible • Further Reading Archival material collated by Douglas Thornton for the Egyptian Diocese Association, now FAPA – Friends of the Province of Alexandria - 2020 1 The Bishops of the Diocese of Egypt 1920- 2020 Llewellyn Gynne 1920- 1946 Geoffrey Allen 1947- 1952 Francis Johnston 1952-58 Kenneth Cragg 1970-1974 Ishaq Mussaad 1974-1978 Ghais Abdel Malik 1983-2000 Mouneer Hanna Anis 2000- 2020 In 1920, the Diocese of Egypt and the Sudan was created with Bishop Llewelyn Gwynne as its Bishop. He was mainly responsible for the building of All Saints’ Cathedral on the banks of the Nile. Bishop Gwynne ordained the first four Egyptian pastors of the Church, including Girgis Bishai, and Adeeb Shammas. The Cathedral on the Nile became an important centre for many of the British forces during the second world war, attracted by the inspiring sermons of Bishop Gwynne who retired in 1946. The diocese of Egypt separated from Sudan and Bishop Gwynne was succeeded in Egypt by Bishop Geoffrey Allen (1947-52), then Bishop Francis Johnston (1952-58) who was followed by Bishop Kenneth Cragg (1970-74). Other leaders included Archdeacons Adeeb Shammas and Ishaq Musaad, and the latter was appointed Bishop in 1974. The Cathedral had to make way for a new bridge over the Nile in 1978. A new design by Dr Awad Kamil Fahmi in the form of a lotus flower was built in Zamalek, adjacent to the Marriott Hotel. -

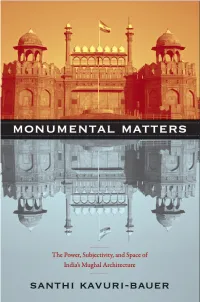

The Power, Subjectivity, and Space of India's Mughal Architecture

monumental matters monumental matters The Power, Subjectivity, and Space of India’s Mughal Architecture Santhi Kavuri-Bauer Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by April Leidig-Higgins Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. In memory of my father, Raghavayya V. Kavuri contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 Breathing New Life into Old Stones: The Poets and Artists of the Mughal Monument in the Eighteenth Century 19 2 From Cunningham to Curzon: Producing the Mughal Monument in the Era of High Imperialism 49 3 Between Fantasy and Phantasmagoria: The Mughal Monument and the Structure of Touristic Desire 76 4 Rebuilding Indian Muslim Space from the Ruins of the Mughal “Moral City” 95 5 Tryst with Destiny: Nehru’s and Gandhi’s Mughal Monuments 127 6 The Ethics of Monumentality in Postindependence India 145 Epilogue 170 Notes 179 Bibliography 197 Index 207 acknowledgments This book is the result of over ten years of research, writing, and discus- sion. Many people and institutions provided support along the way to the book’s final publication. I want to thank the UCLA International Institute and Getty Museum for their wonderful summer institute, “Constructing the Past in the Middle East,” in Istanbul, Turkey in 2004; the Getty Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship during 2005–2006; and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts Grant Award for a subvention grant toward the costs of publishing this book. -

Magazine of the Jerusalem and the Middle East Church Association

Bible Lands Summer 2014 Magazine of the Jerusalem and the Middle East Church Association www.jmeca.org.uk & TH M E M LE ID SA DL RU E E EA J S N T I D H I C O R C E U S H E C O L F A J P E O R C U S S I A P L E E M E H T Jerusalem Egypt & North Africa Cyprus & the Gulf Iran Pupils at the Holy Land Institute for the Deaf in Salt, Jordan greet two bishops (see page 10) Contents include: U.S. PRESIDING BISHOP VISITS JORDAN – page 10 PRIESTS AND IMAMS IN PARTNERSHIP – pages 12-13 and 19 WORLD COUNCIL OF CHURCHES IN IRAN – page 20 THE JERUSALEM AND Bible Lands Editor Letters, articles, comments are welcomed by the Editor: THE MIDDLE EAST CHURCH Canon Timothy Biles, 36 Hound Street, ASSOCIATION Sherborne DT9 3AA Tel: 01935 816247 Email: [email protected] (JMECA) The next issue will be published in November for Winter 2014/15. Founded in 1887 Views expressed in this magazine are not necessarily ‘To encourage support in prayer, money and those of the Association; therefore only signed articles personal service for the religious and other will be published. charitable work of the Episcopal church in JMECA Website www.jmeca.org.uk Jerusalem and the Middle East’. The site has information for each of the four Dioceses Reg. Charity no. 248799 with links to the websites of each one and regular www.jmeca.org.uk updates of Middle East news. -

2016 Yearbook

— THE LIVING STONES OF THE HOLY LAND TRUST _________________________________________________ Registered Charity No. 1081204 'An ecumenical trust seeking to promote contacts between Christian Communities in Britain and those in the Holy Land and neighbouring countries.’ You are permitted to redistribute or reproduce all or part of the contents of the Yearbook in any form as long as it is for personal or academic purposes and non-commercial use only and that you acknowledge and cite appropriately the source of the material. You are not permitted to distribute or commercially exploit the content without the written permission of the copyright owner, nor are you permitted to transmit or store the content on any other website or other form of electronic retrieval system. The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of the contents in its publications. However, the opinions and views expressed in its publications are those of the contributors and are not necessarily those of The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust. The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook and its content are copyright of © The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust. All rights reserved. [email protected] 1 Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2019 2 Contributors Living StoneS Yearbook 2016 i Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2016 ii Contributors Living StoneS Yearbook 2016 The inter-relationship between religion and politics in the Middle East Living StoneS of the hoLY Land truSt Registered charity no. 1081204 iii Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2016 © Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust 2016 all rights reserved. -

Kenneth Cragg's Christian Vocation to Islam

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE CALL TO RETRIEVAL Kenneth Cragg's Christian vocation to Islam A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theology Faculty of Arts University of Birmingham 1987 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS The career of the Anglican scholar and bishop, Kenneth Cragg, focusses attention on the Christian understanding of other faiths in general and of Islam in particular. Cragg has been a leading exponent of a particular missionary approach to Islam, emphasizing that there is a 'mission to Islam' as much as a mission to Muslims. To this end he interprets Islam as pointing in its deepest meaning towards Christianity, a course which has aroused both admiration and opposition among Christians and Muslims alike. I attempt to show that his theology is strongly influenced by distinctive Anglican traditions, and nourished by one particular Arab Christian source. Cragg, however, resists any easy classification, and faces the accusation of theological evasiveness as well as hermeneutic sleight of hand. -

Nahdlatul Ulama – Traditional Islam and Religious Tolerance

Studies & Comments 12 Richard Asbeck (ed.) Religious Pluralism Modern Concepts for Interfaith Dialogue Imprint ISBN 978-3-88795-384-3 Publisher Copyright © 2010, Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung e.V., Munich Lazarettstr. 33, 80636 Munich, Tel. +49-89-1258-0 E-Mail: [email protected], online: www.hss.de Chairman Dr. h.c. mult. Hans Zehetmair, State Minister ret., Hon. Senator Managing Director Dr. Peter Witterauf Head of Academy for Prof. Dr. Reinhard Meier-Walser Politics and Current Affairs Head of Press, PR & Internet Hubertus Klingsbögl Editorial Office Prof. Dr. Reinhard Meier-Walser (Editor-in-Chief, V.i.S.d.P.) Barbara Fürbeth M.A. (Editorial Manager) Anna Pomian M.A. (Editorial Staff) Claudia Magg-Frank, Dipl. sc. pol. (Editorial Staff) Marion Steib (Editorial Assistant) Print Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung e.V., Munich All rights reserved, in particular the right to reproduction, distribution and translation. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, microfilm, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. The copyright for this publication is held by the Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung e.V. The views expressed by the authors in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. Contents Richard Asbeck Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Philipp W. Hildmann Faith and reason – requirements -

NIFCON) of the Anglican Communion REPORT to the ANGLICAN CONSULTATIVE COUNCIL

ACC15/2012/13/1 The Network for Inter Faith Concerns (NIFCON) of the Anglican Communion REPORT TO THE ANGLICAN CONSULTATIVE COUNCIL NIFCON exists to encourage: • Progress towards genuinely open and loving relationships between Christians and people of other faiths. • Exchange of news, information, ideas and resources relating to inter faith concerns between provinces of the Anglican Communion. • Local contextual and wider theological reflection. • Witness and evangelism where appropriate. • Prayerful and urgent action with all involved in tension and conflict. • Support for people of faith, especially Christians, who live as religious minorities in situations of discrimination or danger. NIFCON does this by: • Networking and meeting; • Communication using various media • Gathering information through its international presidents, management group, correspondents, and contacts support groups. • It has also been charged by the Lambeth Conference to study and evaluate Muslim- Christian relations and report regularly to the Anglican Consultative Council PERSONNEL Presidents of NIFCON The Rt Revd Mouneer Anis, Bishop of Egypt, Province of Jerusalem & the Middle East The Most Revd Paul Keun-Sang Kim, Presiding Bishop, Anglican Church of Korea & Bishop of Seoul) The Rt Revd Timothy Stevens, Bishop of Leicester, Church of England Management Group This group is chaired by the Archbishop of Dublin, the Most Revd Michael Jackson. The group meets two or three times each year in order to take forward the work of the NIFCON. Staff Changes Mrs Clare Amos The Network has been provided with huge and invaluable leadership and inspiration, theological insight, support and fundraising ability by Clare Amos over these last years. We continue to be amazed at what could be achieved in one day each week. -

Whatever Happened to Hindustani?

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO HINDUSTANI? LANGUAGE POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL INDIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY DECEMBER 2012 By Richard Forster Thesis Committee: Ned Bertz, Chairperson Peter H. Hoffenberg Miriam Sharma ii Acknowledgements In the course of completing this thesis and other requirements for the MA degree I have become indebted to numerous individuals as well as several institutions for various forms of encouragement and support. Firstly and above all I want to thank Lorinda and Lichen for putting up with me and my often irascible temperament, almost always without complaint, and for supporting me so selflessly that I have been largely free to pursue my studies over the last several years. Without your hard work and many sacrifices it would surely have been impossible for me to spend so much time trying to learn something more about South Asian history and culture, and I am more grateful to both of you than you can know. Similarly, our extended family in both Australia and the USA have been consistently generous, offering both material and moral support without which this study would have so much more challenging. This thesis concerns aspects of the history of certain South Asian languages, in particular Hindi and Urdu, (or Hindustani), but in a way, Sanskrit and Persian as well. Now that I take stock of my attempts to learn each of these languages I realize that I have been assisted in no small way by a rather large cohort of language teachers, for each of whom I hold enormous fonts of respect, affection and gratitude.