Immigrant Worlds Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 20, 1968 Yu. Andropov to the CPSU CC

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 20, 1968 Yu. Andropov to the CPSU CC Citation: “Yu. Andropov to the CPSU CC,” September 20, 1968, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, RGANI, F. 80, Op. 1, D. 513, Ll. 58-60. Obtained and translated by Mark Kramer. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/188129 Summary: This memorandum from KGB Chairman Andropov to the CPSU Politburo follows up on the initial report from Andropov, Shchelokov, and Malyarov. The document highlights the “malevolent views” of the group that held an unauthorized demonstration in Red Square on 25 August 1968, singling out Pavel Litvinov, Larisa Bogoraz, Viktor Fainberg, and Vadim Delaunay for particular opprobrium. Andropov stresses that the KGB will intensify its crackdown on opposition figures who try to “spread defamatory information about Soviet reality.” Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Blavatnik Family Foundation. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document Secret Copy No. 1 USSR ___ Committee of State Security of the USSR under the USSR Council of Ministers ______ 20 September 1968 No. 2205-A Moscow To the CPSU CC By way of addendum to our No. 2102 from 5 September 1968, I am reporting that the Moscow procurator, in contact with the Committee of State Security, has completed the investigation and is remanding to the court the criminal case charging L. I. BOGORAZ-BRUKHMAN (the wife of the imprisoned writer [Yulii] Daniel), P. M. LITVINOV, K. I. BABITSKII, V. I. FAINBERG, V. A. DREMLYUGA, and V. N. DELAUNAY. The guilt of these people in staging disturbances on Red Square on 25 August 1968 was confirmed by the testimony of multiple witnesses and by material evidence that was confiscated. -

List of Participants to the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

HSP HSP/WUF/3/INF/9 Distr.: General 23 June 2006 English only Third session Vancouver, 19-23 June 2006 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM 1 1. GOVERNMENT Afghanistan Mr. Abdul AHAD Dr. Quiamudin JALAL ZADAH H.E. Mohammad Yousuf PASHTUN Project Manager Program Manager Minister of Urban Development Ministry of Urban Development Angikar Bangladesh Foundation AFGHANISTAN Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Dhaka, AFGHANISTAN Eng. Said Osman SADAT Mr. Abdul Malek SEDIQI Mr. Mohammad Naiem STANAZAI Project Officer AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN Ministry of Urban Development Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Musa ZMARAY USMAN Mayor AFGHANISTAN Albania Mrs. Doris ANDONI Director Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Telecommunication Tirana, ALBANIA Angola Sr. Antonio GAMEIRO Diekumpuna JOSE Lic. Adérito MOHAMED Adviser of Minister Minister Adviser of Minister Government of Angola ANGOLA Government of Angola Luanda, ANGOLA Luanda, ANGOLA Mr. Eliseu NUNULO Mr. Francisco PEDRO Mr. Adriano SILVA First Secretary ANGOLA ANGOLA Angolan Embassy Ottawa, ANGOLA Mr. Manuel ZANGUI National Director Angola Government Luanda, ANGOLA Antigua and Barbuda Hon. Hilson Nathaniel BAPTISTE Minister Ministry of Housing, Culture & Social Transformation St. John`s, ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 1 Argentina Gustavo AINCHIL Mr. Luis Alberto BONTEMPO Gustavo Eduardo DURAN BORELLI ARGENTINA Under-secretary of Housing and Urban Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Development Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ms. Lydia Mabel MARTINEZ DE JIMENEZ Prof. Eduardo PASSALACQUA Ms. Natalia Jimena SAA Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Session Leader at Networking Event in Profesional De La Dirección Nacional De Vancouver Políticas Habitacionales Independent Consultant on Local Ministerio De Planificación Federal, Governance Hired by Idrc Inversión Pública Y Servicios Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ciudad Debuenosaires, ARGENTINA Mrs. -

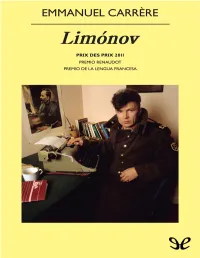

Limonov Emmanuel Carrère, 2011 Traducción: Jaime Zulaika Goicoechea

«Limónov no es un personaje de ficción. Existe y yo lo conozco», advierte Emmanuel Carrère. Esta novela biográfica o biografía novelada reconstruye la vida de un personaje real que parece surgido de la ficción. Un personaje desmesurado y estrafalario, con una peripecia vital casi inverosímil, que le permite al autor trazar un contundente retrato de la Rusia de los últimos cincuenta años y al mismo tiempo aventurarse en una indagación deslumbrante sobre las paradojas de la condición humana. Poeta y pendenciero en su juventud, Limónov frecuentó los círculos clandestinos de la disidencia en la Unión Soviética, se vio obligado a exiliarse y aterrizó en Nueva York, donde vivió como un vagabundo, fue mayordomo de un millonario y escribió novelas autobiográficas. Siguió haciéndolo cuando se marchó a París y allí alcanzó notoriedad pública con una escandalosa novela sobre sus andanzas neoyorquinas por el lado salvaje. De allí pasó a los Balcanes, donde apoyó hasta las últimas consecuencias la causa serbia, y regresó después a la Rusia poscomunista para fundar un partido nacional bolchevique que fue prohibido. Él acabó en la cárcel, acusado de tentativa de golpe de Estado, y allí escribió más libros, tuvo una experiencia mística y al salir se convirtió en opositor a Putin. Ambiguo, escurridizo y estrambótico, este personaje fascinante y detestable a partes iguales, mitad héroe romántico y mitad majadero abominable, es tan contradictorio y desconcertante que se convierte por derecho propio en carne de novela y en el protagonista de esta espléndida y sorprendente narración, galardonada con el Premio Renaudot, el Premio de la Lengua Francesa 2011 y, en especial, el Prix des Prix 2011, que se elige entre las obras ganadoras de los ocho premios literarios franceses más importantes (Académie française, Décembre, Femina, Flore, Goncourt, Interallié, Médicis y Renaudot). -

1 Communication, Democracy, and Intelligentsia by Dmitri N. Shalin Keywords

Communication, democracy, and intelligentsia by Dmitri N. Shalin Keywords: Intelligentsia, glasnost, perestroika, democracy, distorted communications, embodied communications, emotional intelligence * Dmitri N. Shalin is professor of sociology and director of the UNLV Center for Democratic Culture at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas ([email protected]). 1 Introduction In the early 1990s, a group of Russian and American scholars teamed up to investigate the impact of Gorbachev’s reform on Soviet society, focusing especially on the role the intelligentsia played in fomenting glasnost and perestroika. Results of this collaborative study were published in a volume Russian Culture at the Crossroads: Paradoxes of Postcommunist Consciousness (Shalin, 1996a). The contributors worked on the assumption that perestroika was an irreversible achievement, that distortions the reforms wrought in Russian society would be smoothed out over time. Today, this assumption appears overoptimistic. After nearly twenty years in power, Vladimir Putin dismantled key democratic institutions, badly weakened other, and established a personalistic regime that reversed many political gains brought about by his predecessors. An international team assembled for the present project starts with the premise that we live in the age of counterperestroika. Our focus is still on the intelligentsia and its contribution to dismantling the Soviet system, but now we want to explore the unanticipated consequences of social change threatening the existence of the intelligentsia as a distinct group. Our team includes prominent scholars, writers, and civil rights leaders who illuminate the political agendas and personal choices confronting intellectuals in today’s Russia. Contributors look at the current trends through different lenses, they disagree about the intelligentsia’s past achievements and looming future, yet they all feel the need to examine its local and world-historical significance. -

La Défense Des Droits Humains En Union Soviétique Sous Brejnev

Entre coopération et répression: la défense des droits humains en Union soviétique sous Brejnev. Étude du Groupe Helsinki de Moscou Mémoire Zoé Allen-Mercier Maîtrise en histoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Zoé Allen-Mercier, 2018 ii Résumé Ce mémoire porte sur le Groupe Helsinki de Moscou et son évolution au sein de l’Union soviétique dans les années 1970 et 1980. Celui-ci y est présenté en tant qu’association dissidente originale de par son pouvoir de convergence parmi les sources d’opposition et son succès à mobiliser les instances étrangères à la cause des droits humains en URSS. L’étude se penche plus spécifiquement sur la portée de ses activités à la fois sur la conduite du gouvernement à l’intérieur du pays et sur la création d’un réseau d’activisme au-delà des frontières du régime. En maintenant une approche orientée selon ces deux perspectives, à savoir celle de la politique intérieure de l’URSS et celle de l’évolution du contexte international, il s’agit de mettre en évidence la contribution du groupe à la montée d’une opposition au régime soviétique et à ses pratiques humainitaires, mais également d’en souligner les limites. À travers cette narrative, se révèleront donc les contours du régime soviétique sous Léonid Brejnev, sa nature, ses priorités et son caractère répressif. iii Abstract This thesis focuses on the Moscow Helsinki Group and its evolution in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and 1980s. The Group’s work is presented as an original form of dissidence due to its ability to converge the sources of opposition and its success in mobilizing foreign advocacy groups to the cause of human rights in the USSR. -

To Build a Castle V4+(1).Pdf

About the Book Praise for TO BUILD A CASTLE “Sometimes ironic, sometimes detached, sometimes written in cold fury, but always compelling.” —The New Yorker “This is a landmark book and a human document that remains vital.” —Sir Tom Stoppard, Oscar-winning screenwriter of Shakespeare in Love “Vladimir Bukovsky has written an extraordinary account of his life in the Soviet Union…. Listen closely.” —New York Times “A huge story we must not forget. Even inside prison, a revolt of the mind is possible.” —Masha Alyokhina, co-founder of the anti-Putinist punk rock group Pussy Riot, who read To Build a Castle while serving time as a prisoner of conscience “This book is important.” —Former US President Ronald Reagan “If human bravery were a book, it would be To Build a Castle. Bukovsky’s memoir serves as testimony to the horrors of totalitarianism, a reference manual of the Soviet gulag during the Brezhnev years, and an unforgettable tribute to the courage of dissidents like Bukovsky. Unfortunately, the book is a reminder we still very much need today, when Western moral equivalence would have us believe that such monsters no longer exist. They do, and ‘To Build a Castle’ is an essential guide to understanding them, and how to fight them.” —Garry Kasparov, Chairman of the Human Rights Foundation “Bukovsky is properly outraged, but he is also bitterly amusing.” —TIME Magazine “One of the masterpieces of the period.” —Michael Ledeen, former consultant to the US National Security Council, Department of State, and Department of Defense “A gripping and evocative account of the evil empire from a man who helped bring it down.” —Edward Lucas, Senior Editor, The Economist, author of THE NEW COLD WAR: Putin’s Russia and the Threat to the West “To Build a Castle is a fascinating document of its era, as well as the inspiring story of one man’s courageous battle against a totalitarian state. -

Political Protest and Dissent in the Khrushchev Era

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Political Protest and Dissent in the Khrushchev Era Robert Hornsby A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Russian and East European Studies European Research Institute The University of Birmingham December 2008 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis addresses the subject of political dissent during the Khrushchev era. It examines the kinds of protest behaviours that individuals and groups engaged in and the way that the Soviet authorities responded to them. The findings show that dissenting activity was more frequent and more diverse during the Khrushchev period than has previously been supposed and that there were a number of significant continuities in the forms of dissent, and the authorities’ responses to these acts, across the eras of Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev. In the early Khrushchev years a large proportion of the political protest and criticism that took place remained essentially loyal to the regime and Marxist-Leninist in outlook, though this declined in later years as communist utopianism and respect for the ruling authorities seem to have significantly diminished. -

![Untitled F:Friedlvomgröller F:Friedlvomgröller/I:Jonasmekas, Peterkubelka F:Friedlvomgröller [ 21 ] BUENOS AIRESFESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DECINE INDEPENDIENTE Portrayed](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9149/untitled-f-friedlvomgr%C3%B6ller-f-friedlvomgr%C3%B6ller-i-jonasmekas-peterkubelka-f-friedlvomgr%C3%B6ller-21-buenos-airesfestival-internacional-decine-independiente-portrayed-7819149.webp)

Untitled F:Friedlvomgröller F:Friedlvomgröller/I:Jonasmekas, Peterkubelka F:Friedlvomgröller [ 21 ] BUENOS AIRESFESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DECINE INDEPENDIENTE Portrayed

El cine nos emociona, nos hace reír, nos muestra otras Cinema moves us, it makes us laugh, it shows us realidades y, muchas veces, nos deja enseñanzas que other realities, and many times, it teaches us lessons nos quedan para toda la vida. Todos tenemos una pe- we cherish for the rest of our lives. We all have that lícula favorita que nos marcó y que podríamos ver una one favorite movie that marked us and that we could y mil veces. rewatch a thousand times. Cada película es el resultado del trabajo de muchas Each film is the result of the work of many people personas que, en equipo, se esfuerzan para que disfru- who, as a team, make an effort for us to enjoy all of temos de todo su talento. Detrás de cada documental, their talent. Behind every documentary, fiction, dra- ficción, drama o comedia, hay actores, actrices, guionis- ma or comedy, there are actors, actresses, screen- tas, directores, maquilladores y productores que traba- writers, make-up artists and producers who work jan con pasión para que el cine crezca cada día. passionately for cinema to grow every day. En esta nueva edición del BAFICI, vamos a ver el mundo In this new edition of BAFICI, we will see the world a través de los ojos de directores nacionales e inter- through the eyes of local and international directors, nacionales, algunos ya consagrados y otros que recién some of them already established and others who empiezan, independientes. are just starting, independent. Y los vecinos vamos a copar los cines y las calles de la And us neighbors will crowd the theaters and the ciudad para disfrutar de nuevas historias acompañadas streets of the city in order to enjoy new stories with de grandes actuaciones. -

List of Foreign Citizens Illegally Visited Occupied Territories of the Republic

Updated: 18.01.2021 LIST OF FOREIGN CITIZENS ILLEGALY VISITED OCCUPIED TERRITORIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN Date and purpose № Name and surname Citizenship Position of the visit Participated at so called Scientist and journalist 1. Abel Riu Kingdom of Spain “referendum” as an observer on (Catalonia) February 20, 2017 2. Abedi Maryam Gholamreza Islamic Republic of Iran - 2018 Participated at the event held in 3. Abugail Sin Si Ern Republic of Singapore Musician July, 2011 4. Adqur Dzidzariya Georgia/Russian Federation - - Adarya Gushtin 5. Republic of Belarus Journalist May 25, 2016 (Адарья Гуштын) 6. Adam Bennet Schiff United States of America Member of US Congress October, 2019 7. Adrien Buchard French Republic - November, 2019 Member, California State 8. Adrin Nazarian United States of America October 4-9, 2017 Assembly 1 Date and purpose № Name and surname Citizenship Position of the visit 9. Avigdor Eskin State of Israel Journalist April, 2016 Columnist, “Posttimees”; 10. Ahto Lobjakas Republic of Estonia expert, Estonian Foreign - Policy Institute, NGO 11. Agostinho Leitao Portugal - July, 2018 Chairman, “Neptune” 12. Agop Srents Republic of Bulgaria Summer, 2016 Diving Club Director, Kaunas Chamber 13. Egidijus Tamasiunas Republic of Lithuania October, 2012 Theatre 14. Akram Khalief Algeria Blogger February 9-13, 2018 Former adviser to the 15. Alan Yelbakiyev Georgia/Russian Federation “President of South - Ossetia” Alan Robertovich Khugaev 16. (Алан Хугаев Georgia/Russian Federation June 01-09, 2019 Робертович) 17. Ali Bayramoğlu Republic of Turkey Political commentator September 22, 2017 2 Date and purpose № Name and surname Citizenship Position of the visit 18. Ali Sait Çetinoğlu Republic of Turkey Scholar September 22, 2017 Federal Republic of Member of Bundestag, 19. -

II Die Sowjetischen Dissidenten

Universität des Saarlandes Philosophische Fakultät Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften Fachrichtung 4.2 Romanistik Propheten oder Störenfriede? Sowjetische Dissidenten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und Frankreich und ihre Rezeption bei den Intellektuellen (1974—1977) Wissenschaftliche Arbeit zur Erlangung des Diplomgrades Diplom-Kulturwissenschaftlerin (mit Schwerpunkt Deutschland/Frankreich) Eingereicht von: Sonja Hauschild [email protected] Saarbrücken, Mai 2005 II Danksagung Die vorliegende Arbeit ist eine leicht überarbeitete Version meiner im Mai 2005 an der Universität des Saarlandes Saarbrücken und der Université Paul Verlaine Metz vorgeleg- ten Diplomarbeit im Rahmen des integrierten Teildiplomstudienganges Grenzüber- schreitende Deutsch-Französische Studien. Für ihre Unterstützung von der ersten Idee bis zur Abgabe dieser Arbeit möchte ich mich zuallererst bei meinen drei Betreuern be- danken – Herrn Prof. Dr. Rainer Hudemann von der Universtät des Saarlandes, Herrn Prof. Dr. Michel Grunewald von der Université Paul Verlaine Metz und Herrn Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Boll vom Historischen Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung –, die sich auf das Wagnis einer „trinationalen Arbeit“ eingelassen haben und mir mit wertvol- len Hinweisen, der Vermittlung von Kontaktpersonen und ihrer fachlichen Kompetenz stets zur Seite standen. Desweiteren danke ich Johano Strasser für seine Gastfreundschaft, das interessante Ge- spräch und die Möglichkeit sein Privatarchiv der Zeitschrift L’76 einzusehen. Ebenso nahm sich Roselyne Chenu Zeit, mit mir ihre persönlichen Erinnerungen an Pierre Em- manuel weiter zu geben. Bei Pierre Grémion, Directeur de Recherche am CNRS in Pa- ris, möchte ich mich für seine Einschätzungen und Anregungen hinsichtlich der Rezepti- on der Dissidenten in Frankreich herzlich bedanken. Wertvolle Hinweise und Tipps ga- ben mir auch Alfred Grosser, Carola Stern und Richard Picht. -

(DEVELOPMENT and PLANS, 1978-81) 0006.Pdf

r-Ap,r3 Sig6}1PJF COMPT 71-45V 14 A R. A j97 MEMORANDUM FOR: Director of Central Intelligence VIA: Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Deputy Director for Operations Chief, International Activities Division FROM: Chief, IAD/Covert Action Staff SUBJECT: ..,,Pr9gress ,Jtep,ort on.....-Support - Russian and East European Book Distribution and Publishing 1. Action—Requested: Please release .the:.-attached yemorandilucwhach...is.;-in_response to the ..Assistant to. the President ._for.-Na.tiona.1..-SecurityAffairs request for information.on progress-_ and plans for ,the USSR/Eastern Turopean_bOok distribution a.nd publication program.. . 2. Background: The attached report reflects in part use of th -e—C"2SCC-approved Reserve Release in FY 78. The report also updates the information provided to the SCC in your Memorandum of 15 December 1978 on this same subject. All portions of this document are SECRET. DECLASS IF I ED AND RELEASED 8Yr-1 CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENC`k___ 3 SOURCESMETHODGEXEMPT ION 3B28 NAZI WAR CR IMES DI SCLOSURE ACTC.. DATE 2007 Attachment: A/S cc: DDCI 7.7j.j ATiV .77 :7 ' T. C- : WARNING NOTICE DDEcLET : 7 y, i (- 27 Fe 1999 INTELUGENCE SOURCES AND :.;ETHUDS CET,iTED D9d•S • E. • CONCUR: 9 MAR 1979 ctor for Operations Date DDO/IAD/CAS/SOB/ gL Ipas (27 Feb 79) Distribution: Original - Addressee Watt 1 - DCI Watt 1 - DDCI Watt 1 - Comptroller Watt 1 - Executive Registry 1- DDO Watt 1 DDO Registry Watt 1 C/EPS Watt 1 - C/SE w/o att 1 - C/SE/PO w/o att 1 - C/EUR w/o att 1 - C/IAD/CAS Watt 1 - C/IAD/CAS/PUB Watt 1 - C/IAD/CAS/SOB Watt 1 - C/IAD/CAS/SOB/I Watt 1.1./. -

Sborník GA 2018

GRATIAS AGIT MMXVIII GRATIAS AGIT MMXVIII CENA MINISTERSTVA ZAHRANIČNÍCH VĚCÍ ČESKÉ REPUBLIKY SEZNAM LAUREÁTŮ WATHEQ AL-QSOUS LIST OF LAUREATES JORDÁNSKO / JORDAN HARTMUT BINDER NĚMECKO / GERMANY JANA BRATINKOVÁ SLOVENSKO / SLOVAKIA JAROSLAV HAVELKA ŠVÝCARSKO / SWITZERLAND ESTANISLAO KOCOUREK ARGENTINA JAROSLAV MAŘÍK USA JOSEF OPATRNÝ ČESKO / CZECHIA JANA REICHOVÁ AUSTRÁLIE / AUSTRALIA JIŘÍ ŠÍMA ETIOPIE / ETHIOPIA OTAKAR ŠTORCH ŠVÉDSKO / SWEDEN KATEŘINA VLASÁKOVÁ ŠPANĚLSKO / SPAIN PAMÁTNÍK LIDICE ČESKO / CZECHIA PAŘÍŽSKÝ SOKOL FRANCIE / FRANCE SKUPINA „OSMI STATEČNÝCH“ RUSKO / RUSSIA | GRATIAS AGIT | 5 MUDr. Al-Qsous je již několik let ústřední postavou realizace For several years M.D. Al-Qsous has been the central figure for vládního programu MEDEVAC v Jordánsku, jehož pro- the implementation of the MEDEVAC government programme střednictvím poskytuje vláda ČR přímou lékařskou pomoc in Jordan, through which the Government of the Czech syrským uprchlíkům v místě jejich současného pobytu. Republic has been providing direct medical assistance to MUDr. Al-Qsous působí nejen jako konzultant všech týmů Syrian refugees at the locations of their current residences. českých nemocnic, které se v průběhu roku vystřídají v rámci M.D. Al-Qsous works not only as a consultant for all the programu na jordánském území (jen v roce 2017 čtrnáct týmů teams from the Czech hospitals that during the year alternate shifts in the programme in the Jordanian territory (in 2017 it z ČR a 875 odoperovaných pacientů), ale je i nepostradatelným accounted for fourteen teams from the Czech Republic and 875 organizátorem celkového průběhu misí. Pro zajištění úspěš- patients were operated), but also as an indispensable organiser ného průběhu provádí předvýběr pacientů z uprchlických of the overall courses of the individual missions.