Open Aas195 Thesis Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historique Du Parc Des Buttes-Chaumont

A 175 Parc des Buttes-Chaumont Descriptif général HISTORIQUE DU PARC DES BUTTES-CHAUMONT Par Françoise HAMON, historienne, membre de l’équipe Grünig-Tribel Mai 2001. Publié en ligne avec l’autorisation de l’auteur. Reproduction interdite pour un usage commercial ou professionnel. Historique sous forme de trois chapitres présentés en annexe au descriptif général du concours. Annexe 1 : historique du projet des Buttes-Chaumont Annexe 2 : Liste de la documentation d’archives disponibles relative au parc des Buttes-Chaumont Annexe 3 : Chronologie du parc 1 A 175 Equipe GRUNIG-TRIBEL - Historique du Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, par Françoise HAMON, historienne. I. Annexe 1 : Historique du projet des Buttes Chau- mont a) La genèse Parc des Buttes-Chaumont Descriptif général ⇒ Les origines du jardin paysager Les traités anglais du XVIII˚ siècle consacrés aux jardins ne traitent que des parcs de châteaux et ne portent sur des questions d’esthétique : comment créer des paysages dignes d’être peints, c’est- à-dire pittoresques. En réalité, on cherche surtout, par une rupture subtile avec le paysage rural environnant, à mettre en valeur la demeure aristocratique ainsi que l’exige une société extrêmement hiérarchisée. Autant que les portraits de famille (conversation pieces) destinés à valoriser la lignée, l’aristocratie anglaise apprécie les portraits de maisons (voir le film Meurtre dans un jardin anglais) destinés à renforcer la présence territoriale de leur demeure et sa domination spatiale, dans une tradi- tion encore féodale. Le naturel du jardin paysager sera donc un naturel au second degré, identifiable comme naturel fabriqué. On peut ici jouer sur les mots car ce naturel fabriqué est fondé sur la présence de fabriques : outre les commodités qu’elle offre pour la vie sociale, la multiplication de ces pavillons d’agrément produit des fragments de paysages exotiques (à base de pagodes chinoises ou tentes turques) ou historiques (fondés sur le temple antique ou la ruine médiévale). -

In This Issue in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion

F A L L 2 0 1 3 Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris at the Palais de Chaillot… page 11 The Carlu Gatsby’s Fashions Denver 1926 Pittsburgh IN THIS ISSUE in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion IN THIS ISSUE FALL 2013 FEATURE ARTICLES “Degenerate” Ceramics Revisited By Rolf Achilles . 7 Outside the Museum Doors By Linda Levendusky . 10. Prepare to be Dazzled: Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris . 11. Art Moderne in Toronto: The Carlu on the Tenth Anniversary of Its Restoration By Scott Weir . .14 Fashions and Jewels of the Jazz Age Sparkle in Gatsby Film By Annette Bochenek . .17 Denver Deco By David Wharton . 20 An Unlikely Art Deco Debut: The Pittsburgh Pavilion at the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial International Exposition By Dawn R. Reid . 24 A Look Inside… The Art Deco Poster . 27 The Architecture of Barry Byrne: Taking the Prairie School to Europe . 29 REGULAR FEATURES President’s Message . .3 CADS Recap . 4. Deco Preservation . .6 Deco Spotlight . .8 Fall 2013 1 Custom Fine Jewelry and Adaptation of Historic Designs A percentage of all sales will benefit CADS. Mention this ad! Best Friends Elevating Deco Diamonds & Gems Demilune Stacker CADS Member Karla Lewis, GG, AJP, (GIA) Zig Zag Deco By Appointment 29 East Madison, Chicago u [email protected] 312-269-9999 u Mobile: 312-953-1644 bestfriendsdiamonds.com Engagement Rings u Diamond Jewelry u South Sea Cultured Pearl Jewelry and Strands u Custom Designs 2 Chicago Art Deco Society Magazine CADS Board of Directors Joseph Loundy President Amy Keller Vice President PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Susanne Petersson Secretary Mary Miller Treasurer Ruth Dearborn Ann Marie Del Monico Steve Hickson Conrad Miczko Dear CADS Members, Kevin Palmer Since I last wrote to you in April, there have been several important personnel changes at CADS . -

De Vincennes S Ain T-Mand É 16 Et 18, Avenue Aubert Sortie Sortie Bois De Vincennes B Érault Place Du Général Leclerc Fort Neuf a Sortie Venue R De L Av

V incennes Avenue F och Sortie Château-de-Vincennes FONTENAY-SOUS-BOIS Porte de Vincennes S ain t-Mand é 16 et 18, Avenue Aubert Sortie Sortie Bois de Vincennes B érault Place du Général Leclerc Fort Neuf A Sortie venue R de l Av. du Général De Gaulle o a Da u Hôpital Bégin me t Ave Bla e nue de e nche Nogent r d è e i n la i p T GARE 6 é o Aven P ue du u x ROUTIÈRE B u a el- r l A e e i a r l e n l h e CHATEA U d Fontenay-sous-Bois VINCENNES c u DE é e a r u J a n VINCENNES e e M v CHALET DU LAC R t A o r s u t o e e d d P s u r G s r a a l de A r e Lac de S aint-Mandé n venue Fort de Vincennes i d d u M e t s Minim aréc e es o o hal d C b a y e S t a u n s A A o e R e ve e ou v n t t R e de d ue n l n R Ro i 'Esplanad e de o e e n o u N o t t u og F e m e u e u e n d ESPLANADE t e t u L o d d e L R GR 14 A u a te ST-LOUIS e d c ou R u e s n d e C e v g A T A h n S a ve r ê a e n n t i n m A u e E t e v ' - b s l M d e e l a R a n e e s Bois l n y u o l M d e d u u é il in e n t R d a s im e e é e o G e m u s l u d t LA CHESNAIE s a e s a e PARC FLORAL D e d u B e d l DU ROY e a u l e a Jardin botanique de Paris a n Quartier l h l r e la e v T é C A P G o Carnot n y Lac de s Minime s a é u ra e b G r m d r e i a u e VINCENNES l i d c l l d l e R e s . -

Highlights of a Fascinating City

PARIS HIGHLIGHTS OF A FASCINATING C ITY “Paris is always that monstrous marvel, that amazing assem- blage of activities, of schemes, of thoughts; the city of a hundred thousand tales, the head of the universe.” Balzac’s description is as apt today as it was when he penned it. The city has featured in many songs, it is the atmospheric setting for countless films and novels and the focal point of the French chanson, and for many it will always be the “city of love”. And often it’s love at first sight. Whether you’re sipping a café crème or a glass of wine in a street café in the lively Quartier Latin, taking in the breathtaking pano- ramic view across the city from Sacré-Coeur, enjoying a romantic boat trip on the Seine, taking a relaxed stroll through the Jardin du Luxembourg or appreciating great works of art in the muse- ums – few will be able to resist the charm of the French capital. THE PARIS BOOK invites you on a fascinating journey around the city, revealing its many different facets in superb colour photo- graphs and informative texts. Fold-out panoramic photographs present spectacular views of this metropolis, a major stronghold of culture, intellect and savoir-vivre that has always attracted many artists and scholars, adventurers and those with a zest for life. Page after page, readers will discover new views of the high- lights of the city, which Hemingway called “a moveable feast”. UK£ 20 / US$ 29,95 / € 24,95 ISBN 978-3-95504-264-6 THE PARIS BOOK THE PARIS BOOK 2 THE PARIS BOOK 3 THE PARIS BOOK 4 THE PARIS BOOK 5 THE PARIS BOOK 6 THE PARIS BOOK 7 THE PARIS BOOK 8 THE PARIS BOOK 9 ABOUT THIS BOOK Paris: the City of Light and Love. -

Promenade Dans Le Parc Monceau

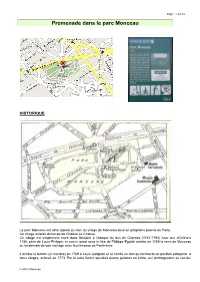

Page : 1 sur 16 Promenade dans le parc Monceau HISTORIQUE Le parc Monceau est ainsi appelé du nom du village de Monceau situé en périphérie proche de Paris. Ce village existait du temps de Charles Le Chauve. Ce village est simplement entré dans l’histoire à l’époque du duc de Chartres (1747-1793) futur duc d’Orléans 1785, père de Louis-Philippe, et connu aussi sous le titre de Philippe Egalité achète en 1769 la terre de Monceau au lendemain de son mariage avec la princesse de Penthièvre. Il achète le terrain (un hectare) en 1769 à Louis Colignon et lui confie en tant qu’architecte un pavillon octogonal, à deux étages, achevé en 1773. Par la suite furent ajoutées quatre galeries en étoile, qui prolongeaient au rez-de- Le Parc Monceau Page : 2 sur 16 chaussée quatre des pans, mais l'ensemble garda son unité. Colignon dessine aussi un jardin à la française c’est à dire arrangé de façon régulière et géométrique. Puis, entre 1773 et 1779, le prince décida d’en faire construire un autre plus vaste, dans le goût du jour, celui des jardins «anglo-chinois» qui se multipliaient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle dans la région parisienne notamment à Bagatelle, Ermenonville, au Désert de Retz, à Tivoli, et à Versailles. Le duc confie les plans à Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle (1717-1806). Ce dernier ingénieur, topographe, écrivain, célèbre peintre et surtout portraitiste et organisateur de fêtes, décide d'aménager un jardin d'un genre nouveau, "réunissant en un seul Jardin tous les temps et tous les lieux ", un jardin pittoresque selon sa propre formule. -

Dvvd Accorhotels Arena

DVVD ACCORHOTELS ARENA PRESS KIT 03 THE ACCORHOTELS ARENA REBIRTH OF AN ICON Ranking as one of the most emblematic structures in the landscape of the capital city, the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy has been reborn under a new light, thanks to the work of the architects from the DVVD agency. Modernized, expanded, upgraded to 21st-century norms and standards, and above all delivered to the public in record time, the new AccorHotels Arena stands out as one of the strong points in the candidature of Paris to host the summer Olympics in 2024. The largest venue for concerts, shows the architectural team of Andrault, and sports events in France, the Parat, Prouvé and Guvan to replace the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy Vel d’Hiv stadium, it rapidly became a (POPB) was opened in February 1984, key venue in the cultural life of Paris. in the 12th arrondissement of the Its blue metallic web structure, its capital. At that time, it formed part sloping lawns and its bold pyramidal of a major urban development project design made a strong imprint upon the for eastern Paris, which was already panorama of the city and captured the exceptionally well-served (thanks to imagination of the public, who thronged the proximity of the Gare de Lyon, the there to attend the performances of RER rapid transit system, the Métro, leading signers or sports stars. From the Right Bank expressway and the funboarding to stock car racing, from Boulevard Périphérique). Designed by Madonna concerts to acrobatic ski-ing, 04 this venue already enjoys a globally unique multi-purpose capability, which has made its reputation. -

Du Chemin Des Roses Aux Épines De La SNCF

Du chemin des roses aux épines de la SNCF Par Daniel Chatelain Qui, parmi les anciens, se souvient de Nation, il sera facile, avec nos deux vélos électriques, via les RER A puis B, d’arriver à la du petit train entre la gare de la Bastille et le gare du Nord, sise, comme chacun sait, à lointain bourg briard de Verneuil-l’Etang (Seine-et- proximité de la gare de l’Est. Marne) le long de la nationale 19 ? Il n’en reste plus que la coulée verte René- Or pour le cyclotouriste il existe deux catégories Dumont de la Bastille à St-Mandé et la branche d’ascenseurs : ceux (de la RATP) où il suffit de sud-est du RER A jusqu’à Boissy-St Léger… et... mettre le vélo en diagonale et ceux (de la SNCF) le « chemin des roses » allant-presque- de Boissy- où il faut cabrer le vélo sur sa roue arrière si vous St Léger à Verneuil-l’Etang. voulez voir la porte se refermer ; et ces deux Son nom vient du train qui acheminait, jusqu’en catégories sont encore plus sensiblement 1939, les roses coupées jusqu’à Paris. distinctes pour l’e.cyclotouriste que nous étions. La concurrence étrangère a fait qu’il n’existe plus Si bien que la sortie de la gare du Nord a qu’une seule roseraie commerciale à Mandres-les- représenté une épreuve de portage du genre Roses la bien nommée. canoë dans des cailloux ; car la qualité de la signalétique de la gare du Nord nous a amenés à prendre chacun deux fois un ascenseur SNCF. -

De La Bastille À Sucy

RANDONNÉE PÉDESTRE DES MARDI 6 ET VENDREDI 9 DÉCEMBRE 2016 DE LA BASTILLE À SUCY …Dis le toi désormais, même s’il est sincère Aucun rêve jamais ne mérite une guerre. On a détruit la Bastille, mais ça n’a rien arrangé, On a détruit la Bastille, quand il fallait nous aimer ! (Jacques Brel) Départ : Place de la Bastille, au pied des marches de l’Opéra, à 9h . Arrivée : Gare R.E.R. de Sucy. Randonnée de 20 km , en terrain plat. Groupes limités à 35 participants . Matin : 11 km : La coulée verte René Dumont (ex Promenade plantée) dans sa totalité et le square Charles Péguy. Le bois de Vincennes d’Ouest en Est, par le GR 14. Après-midi : 9 km : Les bords de Marne, rive droite à Saint-Maur ouest, rive gauche à Créteil. Les îles de Créteil : Brise-Pain, de la Gruyère, des Ravageurs et Ste Catherine. Le pont de Bonneuil, le Moulin Bateau et le confluent du Morbras. Entrée dans Sucy par le quartier des Noyers. Chaussures de randonnée indispensables, le terrain pouvant être très boueux par endroits. Prévoir vêtements adaptés aux conditions climatiques du jour. Si nécessaire, des surchaussures seront distribuées avant d'entrer au restaurant. Possibilité d’abréger : R.E.R. à Joinville. Repas : Vers 12h au restaurant Le Rallye à Saint-Maurice . ℡ : 01 48 89 69 26. Menu Choucroute + dessert. Prix : 18,5 €, apéritif, vin ou bière, café compris. Les suppléments éventuels seront à régler individuellement. Rendez-vous : Gare R.E.R. de Sucy à 8h , pour prendre le R.E.R de 8h13. -

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand Et Le Rayonnement Des Parcs Publics De L’École Française E Du XIX Siècle

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand et le rayonnement des parcs publics de l’école française e du XIX siècle Journée d’étude organisée dans le cadre du bi-centenaire de la naissance de Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand par la Direction générale des patrimoines et l’École Du Breuil 22 mars 2017 ISSN : 1967-368X SOMMAIRE Introduction et présentation p. 4 Carine Bernède, directice des espaces verts et de l’environnement de la Ville de Paris « De la science et de l’Art du paysage urbain » dans Les Promenades de Paris (1867-1873), traité de l’art des jardins publics p. 5 Chiara Santini, docteur en histoire (EHESS-Université de Bologne), ingénieur de recherche à l’École nationale supérieure de paysage de Versailles-Marseille Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, père fondateur d’une nouvelle « école paysagère » p. 13 Luisa Limido, architecte et journaliste, docteur en géographie Édouard André et la diffusion du modèle parisien p. 19 Stéphanie de Courtois, historienne des jardins, enseignante à l’École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Versailles Les Buttes-Chaumont : un parc d’ingénieurs inspirés p. 27 Isabelle Levêque, historienne des jardins et paysagiste Les plantes exotiques des parcs publics du XIXe siècle : enjeux et production aujourd’hui p. 36 Yves-Marie Allain, ingénieur horticole et paysagiste DPLG Le parc de la Tête d’Or à Lyon : 150 ans d’histoire et une gestion adaptée aux attentes des publics actuels p. 43 Daniel Boulens, directeur des Espaces Verts, Ville de Lyon ANNEXES Bibliographie p. 51 -2- Programme de la journée d’étude p. 57 Présentation des intervenants p. -

Mr Agency Wedding Mplarces

MR AGENCY WEDDING MPLARCES... OUR LOCATIONS We manage and operate 15 Parisian locations as well as an exclusive network of 21 partner spaces ranging from high- end apartments with a view such as on the Eiffel Tower, to atypical galleries in the heart of the Marais, castles and domains throughout France. Our venues can accommodate weddings from 20 to 600 people in order to meet both the needs of intimate and extravagant 02 celebrations. Our team is at your disposal to define your criteria for choosing the place of your dreams and to organise venue visits. Keep in mind that we always have a few unpublished treasures and that large venues can be partially privatized to meet your smaller needs. Don’t hesitate to contact us directly. Our services are billed from 3500€/day (tax included) MR AGENCY WEDDING Le rooftop des Lavandes: Rooftop of 135m2 overlooking Paris that can accommodate up to 90 people. Near the Seine River and the Eiffel Tower. 04 L’hôtel des Dahlias: Private mansion of 735m2 located in Paris that can accommodate up to 1000 people. Close to the City Hall of the 7th district. MR AGENCY WEDDING Jardin des Cerisiers: River boat of 500m2 located at the Seine banks that can accommodate up to 350 people. Near to Notre Dame Cathedral. 05 Rooftop des Margherites: Rooftop of 170m2 with extraordinary 360° views of Paris that can accommodate/host up to 80 people. Close to the Arc de Triomphe and the Champs-Élysées.. MR AGENCY WEDDING Château des Sapins: Orangery of 600m2 in the gardens of a castle that can accommodate up to 500 people. -

3 Bis Rue Jean Pierre-Bloch – 75015 PARIS Tél : 01 45 66 59 49 – Email

3 bis rue Jean Pierre-Bloch – 75015 PARIS Tél : 01 45 66 59 49 – Email : [email protected] www.bu.edu/paris SOMMAIRE Page Bienvenue à Paris ! 3 Administrative,Teaching & Internship staff 6-7 American Embassy/Consulate 8 American Embassies around Europe 8 BU Paris Emergency Plan 5 Boston University Center in Paris 6 Boston University abroad 9 Boulangeries, Pâtisseries & Salon de thé 14 Blogs – Paris Life 28 Cabarets & Guinguettes 14 Cafés 15 CellPhones___________ 42-43 Classes (Ceramics, Cooking, Dance) 15-16 Cool hangouts 16 Direction _____________________________________________________________________ 4 Discothèques & Clubs 17 Doctors, Pharmacies 18-19 Counselling 20 Entertainment Listings: Cinema, Clubs, Concerts, Theaters 21 Fitness/Sports 22 Gift ideas from France 23 H1N1 51-53 Hair salons 24 Hostels 25 Hotels 26-27 Internet / Cybercafés 28 Marchés 29-30 Money 31 Museums 32 Organic foods (Bio) 33 Parks & Gardens 34-35 Radio & Television stations 36 Restaurants 37-39 In the neighbourhood, Reasonable, Brunch, Brasseries, Vegetarian, Expensive Safety tips from the U.S. Embassy 10-13 Shopping 40 Supermarkets 41 Telephone 44 Theme parks 44 Tipping 44 Transportation 45-47 Metro, Buses, Airport transportation, Trains, Boat tours Transportation Pass 45 Travel agencies, Shipping 48 University cafeteria information 48 Weather 49 Websites 49 Worship directory 50 Emergency phone numbers 54 2 BIENVENUE A PARIS ! Félicitations! Vous faites partie de Boston University Paris. Ce programme a fêté ses 20 ans en 2009 et a vu défilé plus de 1800 étudiants dans ses murs. Les mois à venir vont marquer un grand tournant dans votre vie et vont devenir une expérience inoubliable. Vous avez l’opportunité unique de vivre et d’étudier ici à Paris, de faire des stages dans des organisations ou des entreprises tout en goûtant à une autre culture, vibrante et variée. -

Des Jardins Et Des Hommes MARCEL VILLETTE

L’entreprise MARCEL VILLETTE Des jardins et des hommes Arnaud Berthonnet SOMMAIRE 5 PRÉFACE Témoignage de Michel Villette 6 AVANT-PROPOS HISTORIQUE La création de jardins, un art millénaire 11 1ÈRE PARTIE - 1929-1984 La société d’espaces verts Marcel Villette, une pionnière dans son métier 31 2E PARTIE - 1985-2007 Un nouveau souffle et des chantiers phares en Île-de-France 41 3E PARTIE - 2008-2018 Des savoir-faire d’excellence au cœur de la transition écologique 51 LES GRANDS CHANTIERS QUI FONT RÉFÉRENCE - 2008-2018 60 ENTRETIEN AVEC ARMAND JOYEUX Quatre questions au président de l’entreprise Marcel Villette ATTELAGE PERCHERON AU PARC DES CHANTERAINES. PRÉFACE Témoignage de Michel Villette Après avoir obtenu le diplôme de paysagiste, j’ai eu la chance avaient entraîné des retards dans les travaux d’aménagements de travailler plusieurs mois avec le Maître Isamu Noguchi* qui a routiers aux abords immédiats de l’aéroport, nous avons dû créé et réalisé le « jardin de la paix » à l’UNESCO. À son contact, maintenir des équipes renforcées et travailler 60 heures par j’ai appris que chaque arbre, chaque plante, chaque cours semaine pour que les travaux sur l’esplanade soient terminés d’eau, chaque pierre et que chaque détail doit être réfléchi à temps. dans un rapport avec les autres éléments de l’aménagement. Cette leçon m’a servi pour tous les aménagements que Les travaux furent terminés à temps pour l’inau guration, et l’Entreprise Marcel Villette a réalisés. à la satisfaction générale. Ce chantier m’a appris que le plus important était de trouver très rapidement des solutions pour Pendant les trente-quatre mois du service militaire, j’ai fait s’adapter à tous les problèmes rencontrés.