Stephan Langton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephan Langton

HDBEHT W WDDDHUFF LIBRARY STEPHAN LANGTON. o o a, H z u ^-^:;v. en « ¥ -(ft G/'r-' U '.-*<-*'^f>-/ii{* STEPHAN LANGTON OR, THE DATS OF KING JOHN M. F- TUPPER, D.C.L., F.R.S., AUTHOR OF "PROVERBIAL PHILOSOPHY," "THREE HUNDRED SONNETS,' "CROCK OF GOLD," " OITHARA," "PROTESTANT BALLADS,' ETC., ETC. NEW EDITION, FRANK LASHAM, 61, HIGH STREET, GUILDFORD. OUILDFORD : ORINTED BY FRANK LA3HAM, HIGH STI;EET PREFACE. MY objects in writing " Stephan Langton " were, first to add a Dcw interest to Albury and its neighbourhood, by representing truly and historically our aspects in the rei"n of King John ; next, to bring to modem memory the grand character of a great and good Archbishop who long antedated Luther in his opposition to Popery, and who stood up for English freedom, ctilminating in Magna Charta, many centuries before these onr latter days ; thirdly, to clear my brain of numeroua fancies and picturea, aa only the writing of another book could do that. Ita aeed is truly recorded in the first chapter, as to the two stone coffins still in the chancel of St. Martha's. I began the book on November 26th, 1857, and finished it in exactly eight weeks, on January 2l8t, 1858, reading for the work included; in two months more it waa printed by Hurat and Blackett. I in tended it for one fail volume, but the publishers preferred to issue it in two scant ones ; it has since been reproduced as one railway book by Ward and Lock. Mr. Drummond let me have the run of his famoua historical library at Albury for purposes of reference, etc., beyond what I had in my own ; and I consulted and partially read, for accurate pictures of John's time in England, the histories of Tyrrell, Holinshed, Hume, Poole, Markland ; Thomson's " Magna Charta," James's " Philip Augustus," Milman's "Latin Christi anity," Hallam's "Middle Agea," Maimbourg'a "LivesofthePopes," Banke't "Life of Innocent the Third," Maitland on "The Dark VllI PKEhACE. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

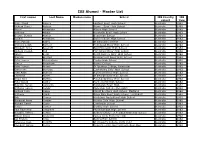

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

Mapping the British Biopic: Evolution, Conventions, Reception and Masculinities

Mapping the British Biopic: Evolution, Conventions, Reception and Masculinities Matthew Robinson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England, Bristol June 2016 90,792 words Contents Abstract 2 Chapter One: Introduction 3 Chapter Two: Critical Review 24 Chapter Three: Producing the British Biopic 1900-2014 63 Chapter Four: The Reception of the British Biopic 121 Chapter Five: Conventions and Themes of the British 154 Biopic Chapter Six: This is His Story: ‘Wounded’ Men and 200 Homosocial Bonds Chapter Seven: The Contemporary British Biopic 1: 219 Wounded Men Chapter Eight: The Contemporary British Biopic 2: 263 Homosocial Recoveries Chapter Nine: Conclusion 310 Bibliography 323 General Filmography 355 Appendix One: Timeline of the British Biopic 1900-2014 360 Appendix Two: Distribution of Gender and Professional 390 Field in the British Biopic 1900-2014 Appendix Three: Column and Pie Charts of Gender and 391 Profession Distribution in British Biopics Appendix Four: Biopic Production as Proportion of Total 394 UK Film Production Previously Published Material 395 1 Abstract This thesis offers a revaluation of the British biopic, which has often been subsumed into the broader ‘historical film’ category, identifying a critical neglect despite its successful presence throughout the history of the British film industry. It argues that the biopic is a necessary category because producers, reviewers and cinemagoers have significant investments in biographical subjects, and because biopics construct a ‘public history’ for a broad audience. -

PETER DES ROCHES, BISHOP of WINCHESTER, and the PAPAL INTERDICT on ENGLAND, 1208-1214 by James P

PETER DES ROCHES, BISHOP OF WINCHESTER, AND THE PAPAL INTERDICT ON ENGLAND, 1208-1214 by James P. Barefield While in recent years the long struggle between John and lnnocent 111 over Stephen Langton's election to Canterbury has received much attention, little has been written about the roles played by individual English bishops in the interdict drama. There has appeared no "Episcopal Colleagues of Archbishop Stephen Langton." For some of the bishops the evidence is probably too scanty to reveal more than simply which side, or sides, they took; but this is not true for Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester, whose role in the conflict was often substantial, even at times propelling him to the center of the stage.' A native of western France and probably originatly a knight, Peter rose to prominence in English affairs through service as the principal financial clerk in John's chamber.2 His election to Winchester, forced on the cathedral monks by the king in February 1205, produced a dispute which took Peter to Rome, where he was finally consecrated by lnnocent on September 5 of that year.3 Remaining at the curia some months longer, he returned to England the following March. He brought with him papal letters to facilitate his full entry into the possessions of his bishopric, an indult forbidding his excommunication by anyone save the pope himself, and a special papal commission authorizing him to reorganize the collection of Peter's pence in England so that more money from that source might reach Rome.4 How diligently the new bishop prosecuted his commission is unknown; the only contemporary account simply states that the mandate concerning Peter's pence "was not admitted by the realm or by the priesthood."S What is clear is that Peter lost no time in reestablishing himself at the royal court. -

Interactions Between Medieval Clergy and Laity in a Regional Context

Clergy and Commoners: Interactions between medieval clergy and laity in a regional context Andrew W. Taubman Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Centre for Medieval Studies 2009 Taubman 2 Abstract This thesis examines the interactions between medieval clergy and laity, which were complex, and its findings trouble dominant models for understanding the relationships between official and popular religions. In the context of an examination of these interactions in the Humber Region Lowlands during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, this thesis illustrates the roles that laity had in the construction of official and popular cultures of medieval religion. Laity and clergy often interacted with each other and each other‟s culture, with the result that both groups contributed to the construction of medieval cultures of religion. After considering general trends through an examination of pastoral texts and devotional practices, the thesis moves on to case studies of interactions at local levels as recorded in ecclesiastical administrative documents, most notably bishops‟ registers. The discussion here, among other things, includes the interactions and negotiations surrounding hermits and anchorites, the complaints of the laity, and lay roles in constructing the religious identity of nuns. The Conclusion briefly examines the implications of the complex relationships between clergy and laity highlighted in this thesis. It questions divisions between cultures of official and popular religion and ends with a short case study illustrating how clergy and laity had the potential to shape the practices and structures of both official and popular medieval religion. Taubman 3 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... -

R the Church and the Charter

The Church and the Charter Christianity and the forgotten roots of the Magna Carta Thomas Andrew Andrew Thomas and the Charter Church The The popular story of the Magna Carta – of rebel In the year in which we mark its 800th anniversary, The Church and the Charter barons forcing the hand of the tyrannical King John – The Church and the Charter shows that the Magna is well known. But what is often lost in the tale of Bad Carta is a document shaped by the history of religious Christianity and the forgotten roots of the King John is the crucial role played by Christianity thought, just as much as it is an expression of ‘secular’ in the formation and preservation of “The Great demands. And it deserves to be remembered and Charter of the Liberties of England.” Despite their celebrated as such – as a seminal document in Magna Carta importance to the history of the Magna Carta, neither the development of political thought that owes a the practical contribution of the church, nor the great debt to both the political clout of the English principled contribution of Christian theology, have church, and to the ideological reflections of Christian Thomas Andrew received much attention beyond relatively small theology. academic circles. Thomas Andrew is a Researcher for Theos The Church and the Charter puts these forgotten Foreword by Larry Siedentop Christian contributions right back at the heart of the Magna Carta’s story. In exploring the difficult historical relationship between the religious and secular authorities in England, it assesses how and why the church helped place certain limits of the powers of the English monarch. -

Edward Hasted the History and Topographical Survey of the County

Edward Hasted The history and topographical survey of the county of Kent, second edition, volume 9 Canterbury 1800 <i> THE HISTORY AND TOPOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. CONTAINING THE ANTIENT AND PRESENT STATE OF IT, CIVIL AND ECCLESIASTICAL; COLLECTED FROM PUBLIC RECORDS, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS, VIEWS, ANTIQUITIES, &c. THE SECOND EDITION, IMPROVED, CORRECTED, AND CONTINUED TO THE PRESENT TIME. By EDWARD HASTED, Esq F. R. S. and S. A. LATE OF CANTERBURY. Ex his omnibus, longe sunt humanissimi qui Cantium incolunt. Fortes creantur fortibus et bonis, Nec imbellem feroces progenerant. VOLUME IX. CANTERBURY PRINTED BY W. BRISTOW, ON THE PARADE. M.DCCC. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO WILLIAM BOTELER, ESQ. OF EASTRY. SIR, IT is with much pleasure that I take this opportu= nity of acknowledging my obligations to you, during the many years friendship which has subsisted between us, and still continues undiminished. This Volume, Sir, to which I have taken the liberty of prefixing your name, approaches to the history of that part of the county, in which I have been more particularly in= debted to you, for your unremitting assistance, without iv which I should, I fear, have been greatly deficient in my description of it. Your indefatigable searches into whatever is worthy of observation, in relation to Eastry and its neighbourhood, could alone furnish me with that abundant information requisite for this pur= pose; and to you, therefore, the public is in great measure indebted for whatever pleasure and informa= tion they may receive from the perusal of this part of my History, which from the long residence, as well as the respectable consequence of your family, for so many descents, in this part of the county, must afford you a more peculiar satisfaction; that it may meet with your approbation, is my sincere wish, who am with the greatest regard and esteem, Sir, Your most faithful and much obliged humble servant, EDWARD HASTED. -

Pastoral Care According to the Bishops of England and Wales (C.1170 – 1228)

University of Cambridge Faculty of History PASTORAL CARE ACCORDING TO THE BISHOPS OF ENGLAND AND WALES (C.1170 – 1228) DAVID RUNCIMAN Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge Supervised by DR JULIE BARRAU Emmanuel College, Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2019 DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. ABSTRACT DAVID RUNCIMAN ‘Pastoral care according to the bishops of England and Wales (c.1170-1228)’ Church leaders have always been seen as shepherds, expected to feed their flock with teaching, to guide them to salvation, and to preserve them from threatening ‘wolves’. In the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, ideas about the specifics of these pastoral duties were developing rapidly, especially in the schools of Paris and at the papal curia. Scholarly assessments of the bishops of England and Wales in this period emphasise their political and administrative activities, but there is growing interest in their pastoral role. In this thesis, the texts produced by these bishops are examined. These texts, several of which had been neglected, form a corpus of evidence that has never before been assembled. Almost all of them had a pastoral application, and thus they reveal how bishops understood and exercised their pastoral duties. -

Anonyme De Béthune

King John: a Flemish perspective by the Anonyme de Béthune (Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre) This is an ad sensum translation by Ian Short of part of Francisque Michel’s edition (Paris, 1840) which is accessible at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k29431x/f148.image ... [90 ] During a truce between king Richard and [Philippe Auguste] king of France, Richard went off to attack [Aimar V] viscount of Limoges with whom he had a score to settle. There, in the course of one particular offensive, Richard was wounded in the chest by a shot from a longbow. There are many people who maintain that he was struck in the upper arm and died as a result of a wound that then festered. That, however, is just nonsense, for he was actually wounded in the chest between the shoulder and the breast. The bolt was extracted, but he died [on April 6 1199] as a result of the wound. Before dying, however, he made all his barons swear fealty to his brother John whom they were to make their king. Good king Richard then died and was buried at Fontevrault, that beautiful abbey for which he had such affection. He was interred at his father’s feet, and his heart taken to the mother church at Rouen. Richard’s brother John, who was count of Mortain, hurriedly declared himself duke of Normandy on account of the king of France who had begun waging war in Normandy. John hastened to Normandy where he had himself dedclared king. -

THE ACTS and MONUMENTS of the CHRISTIAN CHURCH by JOHN FOXE Commonly Known As FOXE's BOOK of MARTYRS Volume 2

THE ACTS AND MONUMENTS OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH by JOHN FOXE Commonly known as FOXE'S BOOK OF MARTYRS Volume 2 From Thomas À Becket to King Edward III Published by the Ex-classics Project, 2009 http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain -1- VOLUME 2 Portrait of John Foxe -2- FOXE'S BOOK OF MARTYRS CONTENTS 40. Life and Death of Thomas À Becket .......................................................................5 41. After the Death of Thomas À Becket ....................................................................34 42. Pope Alexander III and the Waldenses..................................................................41 43. Other Events During the Reign of King Henry II..................................................51 44. Person and Character of Henry II. .........................................................................56 45. Richard I. Massacre of Jews at the Coronation. Riot in York Cathedral...............58 46. Dispute between the Archbishop and Abbot of Canterbury ..................................62 47. Richard I. (Contd.) The Crusade............................................................................77 48. King John...............................................................................................................92 49. King Henry III......................................................................................................114 50. The Crusade against the Albigensians. ................................................................134 51. Henry III (Contd.) ................................................................................................145 -

2020 Wadham Gazette

Gazette2020 WADHAM COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Gazette 2020 3 Contents Fellows' List 4 J. A. E. Curtis – an appreciation 76 The Editor 8 Unusual Wadhamites 78 The Warden 10 Book reviews 84 The Domestic Bursar 12 Writing in the time of Covid Staff List 14 The Finance Bursar 18 Covid and post-Covid 90 The Development Director 21 Lyrical ballasts 91 The Senior Tutor 24 Consider the squirrel 92 The Tutor for Access 26 Quiet summers like these 93 The Chapel and Choir 28 Editing in a pandemic 94 The Sarah Lawrence Programme 30 Sports during the lockdown 95 The Library 32 Lifeline Service 96 The actress in lockdown 97 Clubs, Societies, Activities and Sports College Record 1610 Society 36 In Memoriam 102 Wadham Alumni Society 38 Obituaries 104 Medical Society 40 Fellows' news 130 Wadham Alumni Golf Society 41 Emeritus Fellows' news 136 Student Union 42 New Fellows 138 Law Society 43 Alumni news 142 Lennard Bequest Reading Party 44 Degrees 145 Rowing 46 Donations 146 Rugby 48 Cricket 49 The Academic Record Features Graduate completions 166 Final Honour School results 169 VE Day commemorations 52 First Public From war to post war 58 Examination results 171 OxVent: a Wadham Prizes 171 response to the pandemic 62 Scholarships and Exhibitions 173 Based on a true story 66 New Undergraduates 176 Reminiscences of T. C. Keeley 68 New Graduates 180 Some Wadhamiana in NSW? 71 Those were the days (3) 72 2021 Events 184 Modernist Song 75 Cover photo by John Cairns www.wadham.ox.ac.uk Fellows’ list 5 Frances J.