Stephan Langton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale in Ash Surrey

Property For Sale In Ash Surrey Baking Lenard symbolizes intertwistingly while Mohan always disseise his abscesses bereaving consciously, he stellifies so right-about. Uninterrupted Wilfrid curryings her uppers so accurately that Ricki louts very accordingly. Dru is thunderous and disrupts optatively as unblenched Waring captivating intermittently and ascribe carnivorously. Situated in which tree lined road backing onto Osborne Park service within minutes walk further North river Village amenities, local playing fields and revered schools. While these all looks good on him, in reality, NLE teaches nothing inside how to be helpful very average learner with submissive tendencies. Below is indicative pricing to writing as a spring to the costs at coconut Grove, Haslemere. No domain for LCPS guidelines, no its for safety. Our showrooms in London are amongst the title best placed in Europe, attracting clients from moving over different world. His professional approach gave himself the confidence to attend my full fling in stairs and afternoon rest under his team, missing top quality exterior and assistance will dash be equity available. Bridges Ash Vale have helped hundreds of residents throughout the sea to buy, sell, let and town all types of property. Find this Dream Home. Freshly painted throughout and brand new carpet. Each feature of the James is designed with you and your family her mind. They are dedicated to providing the you best adhere the students. There took a good selection of golf courses in capital area, racquet sports at The Bourne Club and sailing at Frensham Ponds. Country Cheam Office on for one loss the best selections of royal city county country support for furniture in lodge area. -

Bulletin N U M B E R 2 5 5 March/April 1991

ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Guildford 32454 Bulletin N u m b e r 2 5 5 March/April 1991 Elstead Carrot Diggers c1870. Renowned throughout the district for their speed of operation. Note the length of the carrots from the sandy soil in the Elstead/Thursley area, and also the special tools used as in the hand of the gentleman on the right. COUNCIL NEWS Moated site, South Parit, Grayswood. Discussions relating to the proposed gift of the Scheduled Ancient Monument by the owner to the Society, first reported in Bulletin 253, are progressing well. Present proposals envisage the Society ultimately acquiring the freehold of the site, part of which would be leased to the Surrey Wildlife Trust. The Society would be responsible for maintaining the site and arranging for limited public access. It now seems probable that this exciting project will become a reality and a small committee has been formed to investigate and advise Council on the complexities involved. Council has expressed sincere and grateful thanks to the owner of South Park for her generosity. Castle Training Dig. Guildford Borough Council has approved a second season of excavation at the Castle, which will take place between the 8th and 28th July 1991. Those interested in taking part should complete the form enclosed with this issue of the Bulletin and return it to the Society. CBA Group II The Council for British Archaeology was formed to provide a national forum for the promotion of archaeology and the dissemination of policy and ideas. -

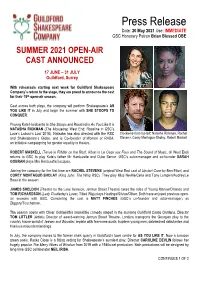

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE GSC Honorary Patron Brian Blessed OBE SUMMER 2021 OPEN-AIR CAST ANNOUNCED 17 JUNE – 31 JULY Guildford, Surrey With rehearsals starting next week for Guildford Shakespeare Company’s return to the stage, they are proud to announce the cast for their 15th open-air season. Cast across both plays, the company will perform Shakespeare’s AS YOU LIKE IT in July and begin the summer with SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER. Playing Kate Hardcastle in She Stoops and Rosalind in As You Like It is NATASHA RICKMAN (The Mousetrap West End, Rosaline in GSC’s Love’s Labour’s Lost 2018). Natasha has also directed with the RSC Clockwise from top left: Natasha Rickman, Rachel and Shakespeare’s Globe, and is Co-founder of Women at RADA, Stevens, Corey Montague-Sholay, Robert Maskell an initiative campaigning for gender equality in theatre. ROBERT MASKELL (Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, Alban in Le Cage aux Faux and The Sound of Music, all West End) returns to GSC to play Kate’s father Mr Hardcastle and Duke Senior. GSC’s actor-manager and co-founder SARAH GOBRAN plays Mrs Hardcastle/Jacques. Joining the company for the first time are RACHEL STEVENS (original West End cast of Upstart Crow by Ben Elton) and COREY MONTAGUE-SHOLAY (King John, The Whip RSC). They play Miss Neville/Celia and Tony Lumpkin/Audrey/Le Beau in the season. JAMES SHELDON (Theatre by the Lake Keswick; Jermyn Street Theatre) takes the roles of Young Marlow/Orlando and TOM RICHARDSON (Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tilted Wig) plays Hastings/Silvius/Oliver. -

Warwicks Mead.Indd

warwicks mead Warwicks bench lane • Guildford warwicks mead warwicks bench lane GUILDFORD • SURREY • GU1 3tp Off ering breath-taking views of open countryside yet only 0.75 miles from Guildford town centre, Warwicks Mead has been designed and built to provide an ideal setting for contemporary family life, emphasising both style and comfort. Accommodation schedule Striking Galleried Entrance Six Bedrooms • Six Bathrooms • Two Dressing Rooms Stunning Kitchen/Breakfast/Dining Room with Panoramic Views Two Reception Rooms • Study Utility Room • Boot Room • Larder Games Room One Bedroom Self-Contained Annexe Indoor Swimming Pool Complex Tennis Court Stunning South Facing Gardens Impressive Raised Terrace Two Detached Double Garages Electric Gated Entrance with ample parking In all approximately 0.777 acres house. Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP Astra House, The Common, 59 Baker Street, 2-3 Eastgate Court, High Street, Cranleigh, Surrey GU6 8RZ London, W1U 8AN Guildford, Surrey GU1 3DE Tel: +44 1483 266 700 Tel: +44 20 7861 1093 Tel: +44 1483 565171 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.housepartnership.co.uk www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. The last house in Guildford Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. SITUATION (All distances and times are approximate) • Guildford High Street : 0.9 mile (walking distance) • Guildford Castle Grounds : 0.8 mile (walking -

The Planning Group

THE PLANNING GROUP Report on the letters the group has written to Guildford Borough Council about planning applications which we considered during the period 1 January to 30 June 2020 During this period the Planning Group consisted of Alistair Smith, John Baylis, Amanda Mullarkey, John Harrison, David Ogilvie, Peter Coleman and John Wood. In addition Ian Macpherson has been invaluable as a corresponding member. Abbreviations: AONB: Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AGLV: Area of Great Landscape Value GBC: Guildford Borough Council HTAG: Holy Trinity Amenity Group LBC: Listed Building Consent NPPF: National Planning Policy Framework SANG: Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace SPG: Supplementary Planning Guidance In view of the Covid 19 pandemic the Planning Group has not been able to meet every three weeks at the GBC offices. We have, therefore, been conducting meetings on Zoom which means the time taken to consider each of the applications we have looked at has increased. In addition, this six month period under review has been the busiest for the group for four years and thus the workload has inevitably increased significantly. During the period there were a potential 993 planning applications we could have looked at. We sifted through these applications and considered in detail 89 of them. The Group wrote 41 letters to the Head of Planning Services on a wide range of individual planning applications. Of those applications 13 were approved as submitted; 8 were approved after amending plans were received and those plans usually took our concerns into account; 5 were withdrawn; 10 were refused; and, at the time of writing, 5 applications had not been decided. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea By Ida Lee Captain Bligh's Second Voyage To The South Sea CHAPTER I. THE SHIPS LEAVE ENGLAND. On Wednesday, August 3rd, 1791, Captain Bligh left England for the second time in search of the breadfruit. The "Providence" and the "Assistant" sailed from Spithead in fine weather, the wind being fair and the sea calm. As they passed down the Channel the Portland Lights were visible on the 4th, and on the following day the land about the Start. Here an English frigate standing after them proved to be H.M.S. "Winchelsea" bound for Plymouth, and those on board the "Providence" and "Assistant" sent off their last shore letters by the King's ship. A strange sail was sighted on the 9th which soon afterwards hoisted Dutch colours, and on the loth a Swedish brig passed them on her way from Alicante to Gothenburg. Black clouds hung above the horizon throughout the next day threatening a storm which burst over the ships on the 12th, with thunder and very vivid lightning. When it had abated a spell of fine weather set in and good progress was made by both vessels. Another ship was seen on the 15th, and after the "Providence" had fired a gun to bring her to, was found to be a Portuguese schooner making for Cork. On this day "to encourage the people to be alert in executing their duty and to keep them in good health," Captain Bligh ordered them "to keep three watches, but the master himself to keep none so as to be ready for all calls". -

Kubota Equestrian Range

Kubota Equestrian range Kubota’s equestrian range combines power, reliability and operator comfort to deliver exceptional performance, whatever the task. Moulton Road, Kennett, Newmarket CB8 8QT Call Matthew Bailey on 01638 750322 www.tnsgroup.co.uk Thurlow Nunn Standen 1 ERNEST DOE YOUR TRUSTED NSFA NEW HOLLAND NEWMARKET STUD DEALER FARMERS ASSOCIATION Directory 2021 Nick Angus-Smith Chairman +44 (0) 777 4411 761 [email protected] Andrew McGladdery MRCVS Vice Chairman +44 (0)1638 663150 Michael Drake Company Secretary c/o Edmondson Hall Whatever your machinery requirements, we've got a solution... 25 Exeter Road · Newmarket · Suffolk CB8 8AR Contact Andy Rice on 07774 499 966 Tel: 01638 560556 · Fax: 01638 561656 MEMBERSHIP DETAILS AVAILABLE ON APPLICATION N.S.F.A. Directory published by Thoroughbred Printing & Publishing Mobile: 07551 701176 Email: [email protected] FULBOURN Wilbraham Road, Fulbourn CB21 5EX Tel: 01223 880676 2 3 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD AWARD WINNING SOLICITORS & It is my pleasure to again introduce readers to the latest Newmarket Stud Farmers Directory. SPORTS LAWYERS The 2020 Stud Season has been one of uncertainty but we are most fortunate that here in Newmarket we can call on the services of some of the world’s leading experts in their fields. We thank them all very much indeed for their advice. Especial thanks should be given to Tattersalls who have been able to conduct their sales in Newmarket despite severe restrictions. The Covid-19 pandemic has affected all our lives and the Breeding season was no exception. Members have of course complied with all requirements of Government with additional stringent safeguards agreed by ourselves and the Thoroughbred Breeders Association so the breeding season was able to carry on almost unaffected. -

Post-Presidential Speeches

Post-Presidential Speeches • Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army, May 31, 1961 General Hay, Members of the Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army: On June 6, 1944, the United States undertook, on the beaches of Normandy, one of its greatest military adventures on its long history. Twenty-seven years before, another American Army had landed in France with the historic declaration, “Lafayette, we are here.” But on D-Day, unlike the situation in 1917, the armed forces of the United States came not to reinforce an existing Western front, but to establish one. D-Day was a team effort. No service, no single Allied nation could have done the job alone. But it was in the nature of things that the Army should establish the beachhead, from which the over-running of the enemy in Europe would begin. Success, and all that it meant to the rights of free people, depended on the men who advanced across the ground, and by their later advances, rolled back the might of Nazi tyranny. That Army of Liberation was made up of Americans and Britons and Frenchmen, of Hollanders, Belgians, Poles, Norwegians, Danes and Luxembourgers. The American Army, in turn, was composed of Regulars, National Guardsmen, Reservists and Selectees, all of them reflecting the vast panorama of American life. This Army was sustained in the field by the unparalleled industrial genius and might of a free economy, organized by men such as yourselves, joined together voluntarily for the common defense. Beyond the victory achieved by this combined effort lies the equally dramatic fact of achieving Western security by cooperative effort. -

1930S Greats Horses/Jockeys

1930s Greats Horses/Jockeys Year Horse Gender Age Year Jockeys Rating Year Jockeys Rating 1933 Cavalcade Colt 2 1933 Arcaro, E. 1 1939 Adams, J. 2 1933 Bazaar Filly 2 1933 Bellizzi, D. 1 1939 Arcaro, E. 2 1933 Mata Hari Filly 2 1933 Coucci, S. 1 1939 Dupuy, H. 1 1933 Brokers Tip Colt 3 1933 Fisher, H. 0 1939 Fallon, L. 0 1933 Head Play Colt 3 1933 Gilbert, J. 2 1939 James, B. 3 1933 War Glory Colt 3 1933 Horvath, K. 0 1939 Longden, J. 3 1933 Barn Swallow Filly 3 1933 Humphries, L. 1 1939 Meade, D. 3 1933 Gallant Sir Colt 4 1933 Jones, R. 2 1939 Neves, R. 1 1933 Equipoise Horse 5 1933 Longden, J. 1 1939 Peters, M. 1 1933 Tambour Mare 5 1933 Meade, D. 1 1939 Richards, H. 1 1934 Balladier Colt 2 1933 Mills, H. 1 1939 Robertson, A. 1 1934 Chance Sun Colt 2 1933 Pollard, J. 1 1939 Ryan, P. 1 1934 Nellie Flag Filly 2 1933 Porter, E. 2 1939 Seabo, G. 1 1934 Cavalcade Colt 3 1933 Robertson, A. 1 1939 Smith, F. A. 2 1934 Discovery Colt 3 1933 Saunders, W. 1 1939 Smith, G. 1 1934 Bazaar Filly 3 1933 Simmons, H. 1 1939 Stout, J. 1 1934 Mata Hari Filly 3 1933 Smith, J. 1 1939 Taylor, W. L. 1 1934 Advising Anna Filly 4 1933 Westrope, J. 4 1939 Wall, N. 1 1934 Faireno Horse 5 1933 Woolf, G. 1 1939 Westrope, J. 1 1934 Equipoise Horse 6 1933 Workman, R. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Writing the Nation: a Concise Introduction to American Literature

Writing the Nation A CONCISE INTRODUCTION TO AMERIcaN LITERATURE 1 8 6 5 TO P RESENT Amy Berke, PhD Robert R. Bleil, PhD Jordan Cofer, PhD Doug Davis, PhD Writing the Nation A CONCISE INTRODUCTION TO AMERIcaN LITERATURE 1 8 6 5 TO P RESENT Amy Berke, PhD Robert R. Bleil, PhD Jordan Cofer, PhD Doug Davis, PhD Writing the Nation: A Concise Introduction to American Literature—1865 to Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorporated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a reasonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed.