Maittt of $})Tiosfopf)P SOCIOLOGY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

N. W.Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Vol-XVI, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1_901_. VOLUME XVI. N W PROVINCES AN D OUDH. PART I. REPORT BY R. BURN, I.e.s., SUPERINTENDENT, CENSUS OPERA TIONS. ALLAHABAD: PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRESS. 1902. PREFACE. AT a time when official reports are being subjected to a rigorous pruning the production of a report extending to nearly 300 pages may be deemed to require some apology. My obje<>t in the following pages has been two-fold. In the first place, an attempt has been made to describe some general features ()f what may be considered the bewildering jungle of figures contained in the Imperial Tables, for, as the proverb says, it is often hard to see the wood for the trees. Secondly, the extent to which the results of the census are fairly reliable, and the methods of obtaining them, have been indicated as briefly as possible. Enumeration throws much extra work on district office:rs and their subordinates, and to them thanks are due for the successful manner in which it was carried out. The abstraction and tabulation were completed in seven central offices, each in charge of a Deputy Collector, and .six ofthese-Pandit Janardan Joshi, B. Pridamna Krishna, M. Lutf Husain, B. Tulshi Rama, B. Siva Prasada, and Qazi Khaliluddin Ahmad-completed their very trying work with a high standard of excellency. 'rhe heaviest . share fell to B. Pridamna Krishna, who dealt with it admirably, while Pandit Janardan Joshi and B. Siva Prasada ex:celled in devising methods of checking the work apart from those prescribed in the r.ules. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why It Is Needed Today?

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why it is needed today? By Premendra Priyadarshi1 Up to 1931, the Census of India included caste too. This practice was abandoned in 1941 because of protests by the nationalists, and also because it was considered worthless, misleading and a waste of time and energy. Column for religion was continued till 2001 census. Thereafter it was felt to be divisive and abandoned from 2011 census. Yet recently, there have been demands in political establishment for and against the caste census and the Union Government seems to be succumbing to pressures. It is desirable that we examine the perspectives of caste census. Why caste abandoned from census in 1941 The most important reason for abandonment of caste census was the ‗worthlessness‘ of the whole exercise because of inconsistency in caste names, which were not fixed and varied between districts, and with time, high incidence of unreliability of individuals‘ statement about caste etc. The Census Commissioner of India for 1931, J.H. Hutton noted, ―Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of current appellations it is certainly not… 227,000 Ambattans have become 10,000, Navithan, Nai, Nai Brahman, Navutiyan, Pariyari claim about 140,000—all terms unrecorded or untabulated in 1921.‖1 Only explanation for this could be that most of the Ambattans of 1921 changed into some other caste. Similarly, the number of Marathas in Central Provinces and Berar increased from 93,901 in 1911, to 206,144 in 1921.2 This more than 110% increase in number can be explained by the mass mobilization of Kunbis (Kurmi-s) to Marathas during the period. -

Census Report of Karauli State, Rajasthan

CENSUS REPORT OF KARAULI STATE 1931 BY Babu Kiatoor Chand dain, B. A., Census Superintendent, KARAULISTATE, RAJPUTANA. LUCKNOW: PRINTED BY K. D. SETH AT THE NEWVL KISHORE PRESS, 1.933. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAca:. Ihtroducti{)n '0. I-IV Chapter J. Distribution and movement o~ the population. SUbject-ma.tter ... \-1\ Subsidiary tables ... 7-11 Statement of rainfall. cultivated area 1~-13 Chapter II. Population o~ cities, to",,""a and villages. Subject-ma.tter ... H,-Hi SubAidiary table!' 1!J-':U Chapter III. Birth-place and migration. Subject-matter ... Subsidiary tables Chapter IV. Age. Subject-IDS.tter 27-31 Subsidiary tables 32-4-2 Chapter v. Sex. Subject-matter Subsidiary tables Chapter VI. Civil Condition. Subject-matte!' Subsidiary tables Chapter VII. Infirmities. Subject-matter 64-67 Subsidiary tables 68-71 Chapter VIII. Occupation. Subject-matter 72-83 Subsidiary ta.bles 84-104 Chapter IX. Literacy. Subject·matter 105-109 Snbaidia.-ry tableR }, \ 'C<-l.l'3 Chapter x. Language. Subject-matter 114-115 Subsidiary tables 116-11'1 Chapter XI. Religion. S11bject-mattel' US-UJO Subsidiary tables 1!U-l!i!8 Chapter XII. Ra.ce. Tribe and Caste. Subjectrmattel' 1~<&-li6 Subsidiary tablos ... ... UI7-18!1 PROVINCIAL TABLES. PAGE- Tabl. I. Area and Population 138 Table II_ Population of districts by religion and literacy 1340 Table III. Caste 135 Table I V. Language 186 Il\IIPERIAL TABLES. Table I. Area-HouBes and popUlation Karauli State, 1931 137 Table II. Variation in population during the last 50 years 138 Table JII. ToWDS and villages classified by population 139 Table IV. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

O)){|P in SOCIOLOGY

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEPRIVATION OF MUSLIMS IN LOCK AND LAC INDUSTRIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ALIGARH AND HYDERABAD ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IBoctor of $i)tlos;o)){|p IN SOCIOLOGY BY SADAF NASIR UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ARDUL MATIN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND ?50CIAL WORK ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2011 ABSTRACT The title of the thesis is 'Socio-Economic Deprivation of MusUms in Lock and Lac Industries: A Comparative Study of AUgarh and Hyderabad'. The focus of the study is to examine dispossession and loss of downtrodden Muslim workers of Aligarh lock industry and Hyderabad lac industry respectively. Deprivation of Muslim workers have been examined in terms of (a) material deprivation, (b) Social deprivation, (c) multiple deprivation viz. low income, poor housing and unemployment. The present study is primarily based on field work carried out during April 2009 to March 2010 in Aligarh (U.P.) and Hyderabad (A.P.). The objectives of this study are to explore the socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in Aligarh Lock Industry (Uttar Pradesh) and Hyderabad Lac Industry (Andhra Pradesh) within the fi-amework of relative deprivation. Important issues in this study are as follows: (1) Selected socio-economic indicators viz., family backgroimd, education, income, housing status, health and hygiene and political dimension of the respondents are to be assessed in Aligarh and Hyderabad. (2) To explore the causes and consequences of socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in the lock and Lac industries. (3) To examine, whether the Muslim children supplement to their family income? (3) To assess how and why the Muslims in lock and lac industry are socially and economically deprived. -

RT-PCR-19-06-2021- Negative (1).Xlsx

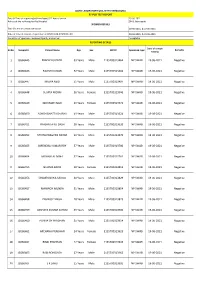

COVID LABORATORY OLD, DHH JHARSUGUDA RT-PCR TEST REPORT Date & Time of reporting(dd/mm/yyyy)//12 hours format 19-06-2021 Adress of the reffering facility/Hospital DHH, Jharsuguda SPCIMEN DETAILS Date & time of sample collection 18-06-2021, & 19-06-2021 Date of time of receipt of specimen at COVID LAB JHARSUGUDA 18-06-2021, & 19-06-2021 Condition of specimen received/Quality and arrival Acceptable REPORTING DETAILS Date of sample SL No. Sample ID Patient Name Age Sex SRF ID Specimen type Remarks testing 1 JSG66445 PRADIP KU PATEL 53 Years Male 2135700313464 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 2 JSG66446 RAJESH KUMAR 52 Years Male 2135700313482 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 3 JSG66447 NRUPA NEGI 51 Years Male 2135700313497 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 4 JSG66448 SUJATA MORAI 26 Years Female 2135700313546 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 5 JSG66449 INDUMATI NAIK 29 Years Female 2135700313572 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 6 JSG66450 ASHISH BHATTACHARYA 49 Years Male 2135700313624 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 7 JSG66451 PRASANTA KU DASH 50 Years Male 2135700313635 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 8 JSG66452 STHITA PRAGYAN NAYAK 30 Years Male 2135700313676 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 9 JSG66453 BIRENDRA KUMAR ROY 57 Years Male 2135700313700 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 10 JSG66454 MOHANLAL MINA 37 Years Male 2135700313761 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 11 JSG66455 NILOMA BARIK 28 Years Female 2135700313812 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 12 JSG66456 DINAKRUSHNA SAHOO 40 Years Male 2135700313829 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 13 JSG66457 MANINGH MUNDA 51 Years Male 2135700313854 -

Hazaribagh, District Census Handbook, Bihar

~ i ~ € :I ':~ k f ~ it ~ f !' ... (;) ,; S2 ~'" VI i ~ ~ ~ ~ -I fI-~;'~ci'o ;lO 0 ~~i~~s. R m J:: Ov c V\ ~ -I Z VI I ~ =i <; » -< HUm N 3: ~: ;;; » ...< . ~ » ~ :0: OJ ;: . » " ~" ;;; C'l ;!; I if G' l C!l » I I .il" '" (- l' C. Z (5 < ..,0 :a -1 -I ~ o 3 D {If J<' > o - g- .,. ., ! ~ ~ J /y ~ ::.,. '"o " c z '"0 3 .,.::t .. .. • -1 .,. ... ~ '" '"c ~ 0 '!. s~ 0 c "v -; '"z ~ a 11 ¥ -'I ~~ 11 CENSUS 1961 BIHAR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 14 HAZARIBAGH PART I-INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CENSUS TABLES AND OFFICIAL STATISTICS -::-_'" ---..... ..)t:' ,'t" -r;~ '\ ....,.-. --~--~ - .... .._,. , . /" • <":'?¥~" ' \ ........ ~ '-.. "III' ,_ _ _. ~ ~~!_~--- w , '::_- '~'~. s. D. PRASAD 0 .. THE IlQ)IAJr AD:uJlIfISTBA'X'lVB SEBVlOE Supwtnundent 01 Oen.ua Operatio1N, B'h4r 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, BIHAR (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. no. IV) Central Government Publications PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics of Bihar, 1951-60 PART I-C Subsidiary Tables of 1961. PART II-A General Population Tables· PART II-B(i) Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV and B-VU)· PAR't II-B(ii) Economic Tables (B-V, B-VI, B-VIII and B-IX)* PART II-C Social and Cultural Tables* PART II-D Migration Tables· PART III (i) Household Economic Tables (B-X to B-XIV)* PART III (ii) Household Economic Tables (B-XV to B-XVII)* PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments· PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Table:,* PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe&* PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Surveys •• (Monoglaphs on 37 selected villages) PART VII-A Selected Crafts of Bihar PART VII-B Fairs and Festivals of Bihar PART VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration * } (Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation PART IX Census Atlas of Bihar.