Court of Protection Practice Direction 9E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Student's Guide to the Leading Law Firms and Sets in the UK

2021 The student’s guide to the leading law firms and sets in the UK e-Edition chambers-student.com Connect with us on cbaK Travers Smith’s mix of formal and informal training is second to none. It enables those coming fresh from law school to quickly become familiar with complex concepts and provides them with the necessary tools to throw themselves into their team’s work right from the start. www.traverssmith.com 10 Snow Hill, London EC1A 2AL +44 (0) 20 7295 3000 Contents Law school The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) p.37 An introduction to the SQE with ULaw p.41 Solicitors’ timetable p.43 Barristers’ timetable p.44 The Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) p.45 The Legal Practice Course (LPC) p.49 The Bar Course p.52 How to fund law school p.55 Law school course providers p.57 Contents https://www.chambersstudent.co.uk The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) From 2021 there’s going to be an entirely new way of qualifying as a solicitor replacing the GDL, LPC and training contract. If you’re thinking ‘SQE OMG!’ – don’t fear: here’s a quick guide. What’s going on? volve a practical testing ‘pilot’ with students. The regula- In winter 2016/17 the Solicitors Regulation Authority tor has stated that it expects various other providers (i.e. (SRA) dropped a bombshell on the legal profession: it was probably law schools and the current GDL/LPC providers) going ahead with its plan for the Solicitors Qualifying Ex- to offer preparatory courses for both stages of the SQE. -

Frequently Asked Questions on Complaints And

Frequently Asked Questions on (iii) All relevant documents/correspondence 9. How does the ASDB deal with a complaint? Complaints and Disciplinary Proceedings Against relevant to the subject-matter of the (a) The ASDB will deliberate on a complaint to ascertain Advocates and Solicitors complaint; and whether there is merit on the issues as alleged; (iv) Chronological narration of all record of (b) Should there be merit in the complaint, the ASDB 1. What type of conduct can a complaint be based on? meetings and phone calls, record of documents may proceed to embark on the following: A complaint may be based on the professional misconduct or and/or correspondence to and/or from third (i) Direct that a DC be constituted to conduct a unsatisfactory professional conduct of a solicitor. party witnesses, and list of potential witnesses formal inquiry; or where applicable. (ii) Issue a Notice to the solicitor to appear to 2. What is professional misconduct? tender an explanation before the Board; and 5. What is the ASDB? Professional misconduct covers a broad range of acts and (c) Should there be no merit in the complaint, the ASDB The ASDB is a statutory body established under section 99(3) circumstances. Examples (the list is not exhaustive) may include: will dismiss the complaint without a formal hearing. (a) Dishonesty/Fraud; of the LPA. It is a body entrusted with powers to conduct (b) Contravening the Legal Profession Act (“LPA”) 1976 disciplinary proceedings against advocates and solicitors and to mete out appropriate punishments. 10. What is the composition of the DC? and any Rules or Rulings made there under; Three members; two of whom shall be legally qualified and one (c) Being found guilty or convicted of a serious offence; 6. -

Statement of Standards for Solicitor Advocates – Performance Indicators

Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 section 25A (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1980/46) Rights of Audience in the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary, the Supreme Court and Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Statutory requirements: 1) Completion to the satisfaction of the Council of a course of training in evidence and pleading in relation to proceedings in the Courts to which rights of audience are sought 2) Has such knowledge as appears to the Council to be appropriate of (1) the practice and procedure of and (2) professional conduct in regard to those Courts 3) That the Council is satisfied that the applicant is, having regard among other things to the applicant’s experience in appropriate proceedings in the sheriff court, otherwise a fit and proper person to have a right of audience in those Courts Rules C4:1 Rights of Audience in the Civil Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules- and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c41-rights-of- audience-in-the-civil-courts/), C4:2 Rights of Audience in the Criminal Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c42-rights-of-audience-in-the-criminal-courts/), C4:3 Order of Precedence, Instructions (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c- specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c43-order-of-precedence,-instructions- and-representation/), and Representation and C4:4 Conduct of Solicitor Advocates (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c44-conduct-of-solicitor-advocates/) apply. -

LAW BRIEFING: Barrister - the Basics

The Careers Service. LAW BRIEFING: Barrister - the basics * Also includes information on Solicitor Advocate* 1) Academic Stage You must have a qualifying UK law degree, ie, an undergraduate law or law/dual degree – check using: www.sra.org.uk/students/academic-stage.page. If your first degree is non-law, you will need to complete a conversion course (GDL/PGDipLaw/CPE) - check providers and fees at: www.lawcabs.ac.uk. For further information about conversion courses see ‘Law Briefing: Getting into Law as a non-law student’. During you studies, find vacation mini-pupillages in chambers. This type of job shadowing/work experience usually lasts no more than a week and is essential to help you understand the work of a barrister and assess if it really is the job for you. Some chambers require applicants to undertake a mini-pupillage at their chambers if they wish to be considered for full pupillage later on. For more help with work experience, see ‘Law Briefing: Work experience’. NB: Most chambers prefer second year applicants. Use your first year to get other forms of work experience, such as court visits. Consider work experience in solicitors firms (made via speculative applications) to reassure yourself that being a barrister is the right choice. Getting non-law experience like a student job, volunteering or involvement in sports, clubs and societies is a great way to develop a range of skills you would need to be a barrister – see ‘Law Briefing: Skills for Lawyers’ and ‘Law Briefing: Commercial Awareness’. Read the legal pages of the newspapers regularly. -

How to Use a Solicitor in England and Wales

How to use a solicitor in England and Wales Easy Read Do you need a solicitor? Solicitors give advice about the law. They are experts and can help you understand your rights and solve different legal problems you may have. There are many areas of law and different legal problems. For example, if you need help with a lease if you want to complain about a service or if you feel you lost your job unfairly. 2 If you need a solicitor you should choose one who knows the law about the problem you have and can help you. This guidance will tell you about what to expect when you use a solicitor. It also tells you how you can get the best and most suitable help for you. Finding a solicitor You can find a solicitor in different ways. Local advice agencies such as a law centre or Citizens Advice Bureau can recommend solicitors. You might like to talk to friends, family or local groups about their experiences. 3 You can also find solicitors through the Law Society at: www.lawsociety.org.uk/ FindASolicitor If you are arrested and kept in custody at a police station you can get free legal advice. If you are charged with a criminal offence and you need to go to court, you may be able to get free legal advice. Meeting your solicitor When you have chosen a solicitor you will need to make an appointment. If you need to see a solicitor urgently the solicitor should try and see you as quickly as possible. -

Defamation and Social Media

Features Defamation and social media Encouraging the public to interact with your organisation through online message boards is increasingly popular, but there are pitfalls in allowing comments to be posted online. Mark Scodie provides guidance to prove that you have taken ‘reasonable care’ as to for organisations on avoiding legal what is published on your page if it bears a set of house rules setting out which kind of contributions liability for defamatory postings are welcome and which are not – making it clear Mark Scodie that abusive, racist, defamatory and/or intimidating Solicitor Many membership organisations and regulatory content will not be tolerated. T: 020 7551 7672 bodies now use social media to raise their profile and [email protected] communicate with stakeholders. However, operating a Secondly, a careful judgement then needs to be made page or message board over which you maintain some about how those rules are to be enforced. Broadly, Mark has wide-ranging editorial control could make you jointly liable for any dispute resolution there are three options: experience servicing defamatory material published on your space by other 1. Pre-moderate every comment before it appears on a number of sectors, social media users. So how do you engage with social the page. (Social media sites vary as to whether coupled with a specialist media whilst guarding against such legal liability? interest in all forms of page operators may do this.) The advantage in media-related disputes. The law of England and Wales provides that anyone doing so is – hopefully – to ensure that no material contributing to the publication of a defamatory is ever published that breaches your own house statement bears joint responsibility for it – journalists, rules or gives rise to any legal complaints. -

Solicitor Not on the Record

Solicitor not on the record Purpose: To provide assistance to barristers who find out that their solicitor is not on the court record Scope of application: All practising barristers Issued by: The Ethics Committee Issued: April 2019 Last reviewed: May 2020 Status and effect: Please see the notice at end of this document. This is not “guidance” for the purposes of the BSB Handbook I6.4. Issue: a barrister is instructed by an instructing solicitor to represent a lay client at a hearing. The barrister is told or finds out that the solicitor is not on the court record. What should the barrister do? Answer: nothing. 1. A barrister can provide reserved legal activities (including advocacy at court) if s/he is instructed by a professional client, a licensed access client or a public access client. There is nothing in the BSB Handbook or the Legal Services Act which requires that the person instructing the barrister to attend court must have conduct of the litigation. 2. Indeed, it is axiomatic that when a barrister is instructed by a licensed access client, the licence holder will not have conduct of the litigation. The same applies in a public access case when the barrister is instructed by an intermediary. 3. The Law Society recognises that solicitors may act for a client on a limited retainer. This is called ‘unbundling’. It is usually so that the client can save money. The Law Society guidance1 says: ‘The essence of unbundling in its purest form is that 1 At the time of review in May 2020, the Law Society guidance was awaiting updating to reflect the replacement of the SRA Handbook (version 21) by the SRA Standards and Regulations on, and with effect, from 25th November 2019. -

Cessation Of/Change in Practice and Disciplinary Proceedings

Cessation of/Change in Practice and Disciplinary Proceedings CHAPTER 13 CESSATION OF/CHANGE IN PRACTICE AND DISCIPLINARY PROCEEDINGS 13.01. Notice to Bar Council (1) An Advocate and Solicitor shall within 14 days of any change: (a) in the address of his/her place of practice; or (b) of his/her place of practice (eg if he/she moves to another firm); notify the Bar Council in writing in the form and manner as the Bar Council may prescribe from time to time and shall comply with the Rules on Cessation of, or Change in, Practice. (2) Any Advocate and Solicitor who: (i) ceases practice as a sole proprietor but continues to practise: (a) as a partner in a firm (other than by reason of the admission of a partner); (b) as an employee; or (c) as a consultant; or (ii) ceases practice as a partner in a firm of Advocates and Solicitors but continues to practise: (a) as a partner in a different firm of Advocates and Solicitors; (b) as a sole proprietor; or (c) as an employee or a consultant; or (iii) ceases practice as an Advocate and Solicitor altogether whether temporarily or permanently; shall within 14 days thereof notify the Bar Council in writing in such form and manner as the Bar Council may require from time to time. 33 Rules and Rulings of the Bar Council (3) Without prejudice to the foregoing the Bar Council may in its discretion impose such terms or conditions on, or give such further or other directions to the Advocate and Solicitor concerned as it may consider appropriate and may require the Advocate and Solicitor concerned to attend before the Bar Council or its nominated committee to provide such clarification or to answer such queries as may be required of, or put to, him/her. -

Practice Note the Official Solicitor to The

PRACTICE NOTE THE OFFICIAL SOLICITOR TO THE SENIOR COURTS: APPOINTMENT IN FAMILY PROCEEDINGS AND PROCEEDINGS UNDER THE INHERENT JURISDICTION IN RELATION TO ADULTS Introduction 1. This Practice Note replaces the Practice Note dated March 2013 issued by the Official Solicitor. 2. It concerns: (a) the appointment of the Official Solicitor as “litigation friend” of a “protected party” or child in family proceedings, where the Family Division of the High Court is being invited to exercise its inherent jurisdiction in relation to a vulnerable adult1 or where proceedings in relation to a child aged 16 or 17 are transferred into the Court of Protection; (b) requests by the court to the Official Solicitor to conduct Harbin v Masterman2 enquiries; and (c) requests by the court to the Official Solicitor to act as, or appoint counsel to act as, an advocate to the court3. The Note is intended to be helpful guidance, but is always subject to legislation including the Rules of Court, to Practice Directions, and to case law. In this Note “FPR 2010” means Family Procedure Rules 2010, “CPR 1998” means Civil Procedure Rules 1998 and “CoPR 2007” means Court of Protection Rules 2007. 3. For the avoidance of doubt, the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (CAFCASS) has responsibilities in relation to a child in family proceedings in which their welfare is or may be in question (Criminal Justice and Court Services Act 2000, section 12). Since 1 April 2001 the Official Solicitor has not represented a child who is the subject of family proceedings (other than in very exceptional circumstances). -

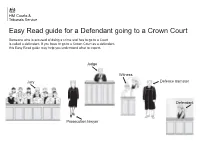

Easy Read Guide for a Defendant Going to a Crown Court

Easy Read guide for a Defendant going to a Crown Court Someone who is accused of doing a crime and has to go to a Court is called a defendant. If you have to go to a Crown Court as a defendant, this Easy Read guide may help you understand what to expect. Judge Witness Jury Defence barrister Defendant Prosecution lawyer What is a Crown Court? If someone tells the police that you have done a crime you may have to go to a Court. Someone who is accused Defendant of doing a crime and goes to a Court is called a defendant. If a defendant is accused of a less serious crime, a Magistrates’ Court will decide what happens to them. An example of a less serious crime is doing graffiti. You can find out more about magistrates’ courts in an easy read guide called Going to a Magistrates’ Court. It is on the internet at: http://hmctsformfinder. justice.gov.uk/ HMCTS/GetLeaflet. do?court_leaflets_id=2646 If a defendant is accused of a more serious crime, a Crown Court will decide what happens to them. An example of a more serious crime is attacking someone. A defendant accused of a less serious crime can choose to go to the Crown Court. Before you go to the Court – getting a solicitor A defence solicitor is someone who helps a Defence defendant with the law. solicitor If you don’t have much money, you may be able to get free help from a solicitor. This is called legal aid. Your defence solicitor Barrister can get you a barrister. -

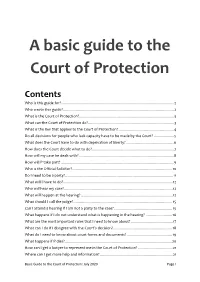

A Basic Guide to the Court of Protection

A basic guide to the Court of Protection Contents Who is this guide for? ................................................................................................................ 2 Who wrote this guide? .............................................................................................................. 2 What is the Court of Protection? .............................................................................................. 3 What can the Court of Protection do? ..................................................................................... 3 What is the law that applies to the Court of Protection? ....................................................... 4 Do all decisions for people who lack capacity have to be made by the Court? .................... 5 What does the Court have to do with deprivation of liberty? ................................................ 6 How does the Court decide what to do? ................................................................................. 7 How will my case be dealt with? .............................................................................................. 8 How will P take part? ................................................................................................................ 9 Who is the Official Solicitor? ................................................................................................... 10 Do I need to be a party? ........................................................................................................... 11 -

What's the Difference Between a Solicitor and a Barrister?

4 Paper Buildings Temple, London EC4Y 7EX T: 020 7427 5200 E: [email protected] W: 4pb.com What’s the difference between a solicitor and a barrister? Historically, barristers were specialists in technical law and court practice and solicitors were litigation managers, working out the case then working the case through from start to finish, and instructing a barrister for advice about the law or court advocacy. Although this is still the case for the most part, it’s fair to say that there isn’t as much of a difference as there used to be. The two sides of the legal profession are coming increasingly closer together with some barristers now authorised to conduct litigation and some solicitors doing court advocacy. However, the skills you need for your case, depending on its particular stage and complexity, will still dictate what kind of specialist is likely to be better for the job you want done. There are other differences too. Solicitors tend to operate as part of a firm, and are therefore more likely to be good at a team approach. Barristers, on the other hand, are generally self-employed and work independently, although they tend to come together in ‘chambers’ (like 4PB) in order to pool administrative and other resources. While solicitors can’t work on both sides of a case, because the firm is acting for a client and not the individual lawyer, barristers from the same chambers can be on both sides of a case as they are independent of each other. The other important distinction between solicitors and barristers is the way they generally tend to charge.