Roman Fish Sauce: Fish Bones Residues and the Practicalities of Supply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Pre-Proof

Journal Pre-proof Toxoplasma gondii infection in meat-producing small ruminants: Meat juice serology and genotyping Alessia Libera Gazzonis, Sergio Aurelio Zanzani, Luca Villa, Maria Teresa Manfredi PII: S1383-5769(20)30010-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2020.102060 Reference: PARINT 102060 To appear in: Parasitology International Received date: 24 October 2019 Revised date: 14 January 2020 Accepted date: 16 January 2020 Please cite this article as: A.L. Gazzonis, S.A. Zanzani, L. Villa, et al., Toxoplasma gondii infection in meat-producing small ruminants: Meat juice serology and genotyping, Parasitology International(2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2020.102060 This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. © 2020 Published by Elsevier. Journal Pre-proof Toxoplasma gondii infection in meat-producing small ruminants: meat juice serology and genotyping. Running title: Toxoplasma gondii in slaughtered sheep and goats Alessia Libera Gazzonis1*, Sergio Aurelio Zanzani1, Luca Villa1, Maria Teresa Manfredi1 1 Department of Veterinary Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, via Celoria 10, 20133 Milan, Italy * Corresponding Author. E-mail address: [email protected]; Phone: +39 02 503 34139. -

Sauces Reconsidered

SAUCES RECONSIDERED Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy General Editor: Ken Albala, Professor of History, University of the Pacific ([email protected]) Rowman & Littlefield Executive Editor: Suzanne Staszak-Silva ([email protected]) Food studies is a vibrant and thriving field encompassing not only cooking and eating habits but also issues such as health, sustainability, food safety, and animal rights. Scholars in disciplines as diverse as history, anthropol- ogy, sociology, literature, and the arts focus on food. The mission of Row- man & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy is to publish the best in food scholarship, harnessing the energy, ideas, and creativity of a wide array of food writers today. This broad line of food-related titles will range from food history, interdisciplinary food studies monographs, general inter- est series, and popular trade titles to textbooks for students and budding chefs, scholarly cookbooks, and reference works. Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nine- teenth Century, by Erica J. Peters Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese, by Ken Albala Food and Social Media: You Are What You Tweet, by Signe Rousseau Food and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century America, by Mark McWilliams Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America, by Bruce Kraig and Patty Carroll A Year in Food and Beer: Recipes and Beer Pairings for Every Season, by Emily Baime and Darin Michaels Celebraciones Mexicanas: History, Traditions, and Recipes, by Andrea Law- son Gray and Adriana Almazán Lahl The Food Section: Newspaper Women and the Culinary Community, by Kimberly Wilmot Voss Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits, and the Return of Artisanal Foods, by Suzanne Cope Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Cul- ture, and Social Influence, by Janet Clarkson Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table, by Kath- erine A. -

Effect of Different Feeding Regimes on Growth and Survival of Spotted

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2018; 6(2): 2153-2156 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Effect of different feeding regimes on growth and JEZS 2018; 6(2): 2153-2156 © 2018 JEZS survival of spotted murrel, Channa Punctatus Received: 19-01-2018 Accepted: 20-02-2018 (Bloch, 1793) larvae Md. Hakibur Rahman Upzilla Fisheries Officer, Department of Fisheries, Md. Hakibur Rahman, Debashis Kumar Mondal, Khondaker Rashidul Bishwamvarpur, Sunamganj, Hasan, Md. Idris Miah, Md. Ariful Islam and Nasima Begum Bangladesh Debashis Kumar Mondal Abstract Senior Scientific Officer, An experiment was conducted to evaluate the effects of different feeds viz., tubifex (T1), chicken intestine Bangladesh Fisheries Research paste (T2) and tilapia fish paste (T3) on the growth and survival of taki, (Channa punctatus) in nine trays. Institute, Brackish water A total of 300 larvae /m2 (average weight 28.70±0.50 mg) was reared for 21 days in each treatment Station, Paikgacha, Khulna, having three replications. The net weight gain of the larvae in T1 (122.30±1.24 mg) was significantly Bangladesh higher (P<0.05) than those of T2 (113.18±1.042 mg) and T3 (104.58±1.30 mg). The percent length gain, percent weight gain, SGR and survival rate were also significantly (P<0.05) higher in T1 (345.90±2.91, Khondaker Rashidul Hasan 426.14±4.33, 7.91±0.04 and 74.00±1.00) than that in T2 (334.91±1.72, 394.34±3.63, 7.61±0.03 and Senior Scientific Officer, 37.67±1.53) and T3 (323.61±2.82, 364.39±4.55, 7.31±0.05 and 34.33±0.58). -

Epi News San Diego Epiphyllum Society, Inc

Epi News San Diego Epiphyllum Society, Inc. August, 2009 Volume 34, Number 8 Page 2 SDES Epi News August, 2009 leads us to the bad news (for SDES) Jill Rowney President‟s Corner: (Peck) is moving to Northern California to be closer to her mother and other family members (good news for I hope everyone is enjoying their Jill, Mom and grandkids). Jill has kindly agreed to summer. We don't have many epies continue doing the newsletter. It is up to the rest of us blooming now but we can take time and smell our to send her info, pictures etc. Her e-mail is on back of roses and other plants. It was Epiphyllum Day at the newsletter, so please help by sending her news items. San Diego Fair on July 3rd. We did have a few Our appreciation dinner will be on August blooms. I think I had five and Phil Peck brought one 22nd. There has been a change of time and loca- bloom and a representative plant, plus we had tion. George French and his daughter Kathy have posters. Ron Crain and Phil both gave two very invited us to have it at their home. Michal agreed to informative talks. Phil had also given a talk on June this and we hope we will see Michal's home next 19th. We had SDES members Velma Crain, year. It will start at 2:00 p.m. and feature BBQ. More Mischa Dobrotin, Gail Eisele, Katelyn Hissong, and information on page 6. myself working at the table and answering questions. -

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Sample Download

UMAMI 1 A Message from the Umami Information Center n pursuit of even more flavorful, healthy cooking, seas researchers. As a result, umami was internation- chefs the world over are turning their attention ally recognized as the fifth taste, joining the existing Ito umami. four basic tastes, and in 2002, the presence of umami Once there were thought to be four basic—or pri- receptors in the taste buds on the tongue was revealed: mary—tastes: sweet, sour, salty and bitter. Until that further scientific proof cementing umami's status as a is, Japanese scientist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda noted the primary taste. presence of another savory taste unexplainable solely In December 2013 “Washoku, traditional dietary by these four. In 1908 Ikeda attributed this fifth taste cultures of the Japanese” was accorded Intangible to the amino acid glutamate found in large quantities Cultural Heritage status by UNESCO. Japanese cui- in kombu seaweed, and dubbed it “umami.” Then sine is currently enjoying a burgeoning international in 1913 Shintaro Kodama found inosinate to be the profile thanks to the growing awareness of healthy umami component in dried bonito flakes (katsuo- eating choices. One characteristic of Japanese food bushi), and in 1957, Dr. Akira Kuninaka discovered is the skillful use of umami to create tasty, healthy umami in guanylate, later identifying guanylate as dishes without animal fats. Umami—a Japanese the umami component in dried shiitake mushrooms. word now internationally recognized—is a key ele- Glutamate, inosinate and guanylate are the three ment in palatability or “deliciousness,” and a focus dominant umami substances, and are found not only of intense interest among people involved in food, in kombu and katsuobushi, but other foods as well. -

Corn on the Cob Maïskolven, Epis De Mais, Maiskolben, Mazorcas De Maíz, Pannocchie Di Mais

Quick-frozen - Diepvries - Surgelé - Tiefgekühlt - Ultracongelado - Surgelato Corn on the cob Maïskolven, Epis de mais, Maiskolben, Mazorcas de maíz, Pannocchie di mais UK | Ardo offers corn cobs in different forms: whole cobs, FR | Ardo propose des épis de maïs de différents formats : half cobs, 1/4 cobs and mini corn cobs. All of them ideal épis de maïs entiers, demi-épis de maïs, ¼ d’épis de for roasting in the oven, grilling or cooking on the maïs et mini épis de maïs. Ils se prêtent parfaitement à barbecue in the summer. Perfect just as they come or de multiples recettes au four, au gril ou au barbecue en with a little butter and a sprinkling of delicious Ardo été. Vous pouvez les préparer nature ou ajouter un peu de herbs or a ready-to-use herbs mix. Ardo’s corn cobs have a beurre et de succulentes épices d’Ardo ou des mélanges typically crunchy bite, aroma and sweet flavour. d’aromates appropriés. Les épis de maïs d’Ardo se démarquent par leur texture croustillante, leur arôme NL | Ardo biedt maïskolven in verschillende vormen aan: et leur saveur sucrée. hele maïskolven, halve maïskolven, maïskolven ¼ en mini maïskolven. De maïskolven lenen zich perfect voor DE | Ardo bietet Maiskolben in verschiedenen Formen an: tal van bereidingen in de oven, onder de grill of in de ganze Maiskolben, halbe Maiskolben, geviertelte zomer op een BBQ. Puur natuur of met toevoeging van Maiskolben und Minimaiskolben. Die Maiskolben wat boter en heerlijke Ardo kruiden of aangepaste krui- eignen sich perfekt für zahlreiche Zubereitungen im denmixes. -

Gerhan Bitters

PROSPECTUS FOR 1865. POUTZ’S AyerS AVKRS D*s*m*e~iA~~ - ¦ Agricultural. | Saturday Evening Post, CELEBRATED ..cs. AND The (tattle DISEASES DESrt.TINT. FROM DISORDERS ——— -—¦ anti ” govsc gouto. and Hast SaFsapariOa;* LIVER & "Ths Oldest of t'uo Wceklie* OF THE DIGESTIVE ORGANS, • Butter ia Winter. ¦ , FOR PURIFYING THE ' AUK CUBED UV igould the iPILJJS- BLOOD, How very difficult it is to find good, 'i MIR pub! iShef&’of the POST call { Arc yon sic’ , .<vb!o, nnd Anil forthcrprviiy cure oft he following cumgluints: SL attention of tl.eir host ofold friends and the Am* ion our Mcrofali :i:ni ArvofulouN AflTcriionH, unch in winter. When- one farmer of ouler, HOOFLAND’3 butter ; public to Ptospicius tor die coming year. with yur’nvhtcm at Tumors. INwrq Kruptionx, their deiniifP'd, md a ((•cling* makes uu aUiactive article, one Immlrei! Pile POST still'continues to ma main its pioud our FimpT-*, Taituli-*, STotrhi'H, Roils, ( in comlortnbk* ?Tlicm*m mp- Dl.tia*i| tttcia me nail all give it to ns vvhtte and iasleless. How ia position as toiiih oiten the include OAKLAND, lull., 6HI June, 185( ). flt & tuts ? Why cannot a general mode he A FIRST GRASS LITERARY PAPKR, to serious illnew*. aome J. (’. Ayer Co. oenla: I f*el it nv duty to no- 1 of ricki****is creeping upon kiiowlerlzn whut vonr SaiHUpahiia has done for mo. I GERHAN ils and numerous col- \on,niid should Ik* melted BITTERS.- manufacturing arrays weekly solid llnving a intectiun, . adopted by dairymen in and right inlieriteil 1 have TONIC) umns of b\ a tiineiv nee ol Hie Miifciei from it in vniioiH way* for yearn. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

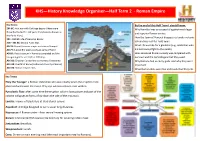

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Menu 1 JAPANESE VS CHINESE BUFFET DINNER

Menu 1 JAPANESE VS CHINESE BUFFET DINNER APPETIZER/SALAD Seasonal seaweed, Marinated baby octopus, Boiled snow beans, Taro with Thai chili sauce, Honey dew melon Prawn, Deep fried bean curd with spicy and sweet sauce, Fried eggplant with dengaku sauce, assorted fresh lettuce, cucumber Japanese, tomatoes cherry, Slice of onion, corn kernel ** Served with Japanese wafu sauce, Sesame dressing, Thousand Island dressing, Caesar dressing, French dressing, Vinaigrette sauce *** SOUP Boiled wantan dumpling with vegetables soup *** SUSHI COUNTER Salmon sashimi, Tuna sashimi, White tuna sashimi, Cucumber roll, Egg roll, California roll, River eel roll, Egg mayo gunkan, Salmon mayo gunkan, corn mayo gunkan, Inari sushi Served with Soya sauce, Wasabi, Pickle Ginger *** TEPPANYAKI AND SHABU-SHABU COUNTER Chicken thigh, Fish, Prawn, Beef, Squid, Mix Vegetables ** Fish ball, Squid ball, Crab ball, Prawn ball, Cocktail sausage, Chicken ball, Chikuwa, Fish cake, Hard boil egg, Quail egg, Fuchuk, Prawn, Crab stick, Narutomaki, Sausage, Tauhu pok, Taro, Carrot, Lotus root, Ladies Finger fish cake, tau pok fish cake, eggplant fish cake, Green capsicum, Red capsicum, Yellow capsicum, Enoki mushroom, Shimeji mushroom, Shitake mushroom, Iringi mushroom, Oyster mushroom, Squid Fresh, Clam, Green half shell mussel, Cockle ** Cha soba, Yamaimo soba, Sanuki udon, Maggie, Chee Chong Fun ** Miso soup, Kim Chee soup, Chicken soup, Bonito soup ** Served with Goma tare sauce, Ponzu sauce, Japanese momeji chili sauce, teriyaki sauce, Chili sauce, Tomato sauce, Japanese