The White Rose Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Stadt Salzburg 1939

Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Die Stadt Salzburg 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation zusammengestellt auf Basis zeitgenössischer Tageszeitungen von Siegfried Göllner Berücksichtigte Tageszeitungen: Salzburger Volksblatt: SVB Salzburger Landeszeitung: SLZ 1 Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Berichte zum Dezember 1938 und Statistiken 1938 31.12.1938 Empfang beim Oberbürgermeister. Unter Führung von Magistratsdirektor Emanuel Jenal finden sich alle städtischen Amtsleiter bei Oberbürgermeister Giger ein, der eine Neujahrsansprache hält. (Teilweiser Abdruck im SVB). SVB, 2.1.1939, S. 7. SLZ, 2.1.1939, S. 6. 31.12.1938 Studenten-Reisegruppe. 84 Studenten aus verschiedenen Ländern besuchen Salzburg im Rahmen ihres Aufenthaltes in Berchtesgaden. SVB, 2.1.1939, S. 8. SLZ, 2.1.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Bilanz Brandschadenversicherung. Die Salzburger Landes-Brandschaden-Versicherungs-Anstalt legt ihre Jahresbilanz 1938 vor. SLZ, 10.11.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Scheidungen zweites Halbjahr. Das neue Eherecht brachte einen sprunghaften Anstieg der Scheidungen im Land Salzburg. Im zweiten Halbjahr 1938 wurden beim Salzburger Landesgericht 313 Ehescheidungsklagen eingebracht (1937: 71). Juli 26 (1937: 11), August 30 (3), September 56 (9), Oktober 88 (16), November 55 (16), Dezember 57 (16). SVB, 10.1.1939, S. 8. SLZ, 9.1.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Bevölkerungsentwicklung viertes Quartal. Das SVB veröffentlicht eine Statistik über die Bevölkerungsentwicklung von Oktober- Dezember 1938 in der Stadt Salzburg. 347 Todesfällen stehen 291 Geburten (davon 64 unehelich) gegenüber. Im gesamten Jahr 1938 gab es 1.327 Todesfälle und 1.036 Geburten. SVB, 22.2.1939, S. 5. 2 Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. -

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

Badw · 019388086

V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 BAYERISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE · JAHRGANG 2004, HEFT 4 Erstversand WALTER ZIEGLER Hitler und Bayern Beobachtungen zu ihrem Verhältnis Vorgetragen in der Sitzung vom 6. Februar 2004 MÜNCHEN 2004 VERLAG DER BAYERISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN In Kommission beim Verlag C. H. Beck München V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 ISSN 0342-5991 ISBN 3 7696 1628 6 © Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften München, 2004 Gesamtherstellung: Druckerei C. H. Beck Nördlingen Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 Inhalt 1. Zur Methode ............................... 8 2. Hitlers Aufstieg in Bayern ...................... 16 3. Im Regime ................................ 33 4. Verhältnis zu den bayerischen Traditionen ........... 73 5. Veränderungen im Krieg ....................... 94 Bildnachweis ................................. 107 V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 Abb. 1: Ein bayerischer Kanzler? Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler bei seiner Wahlrede am 24. -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

Mildred Fish Harnack: the Story of a Wisconsin Woman’S Resistance

Teachers’ Guide Mildred Fish Harnack: The Story of A Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance Sunday, August 7 – Sunday, November 27, 2011 Special Thanks to: Jane Bradley Pettit Foundation Greater Milwaukee Foundation Rudolf & Helga Kaden Memorial Fund Funded in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council, with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the State of Wisconsin. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Introduction Mildred Fish Harnack was born in Milwaukee; attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison; she was the only American woman executed on direct order of Adolf Hitler — do you know her story? The story of Mildred Fish Harnack holds many lessons including: the power of education and the importance of doing what is right despite great peril. ‘The Story of a Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance’ is one we should regard in developing a sense of purpose; there is strength in the knowledge that one individual can make a difference by standing up and taking action in the face of adversity. This exhibit will explore the life and work of Mildred Fish Harnack and the Red Orchestra. The exhibit will allow you to explore Mildred Fish Harnack from an artistic, historic and literary standpoint and will provide your students with a different perspective of this time period. The achievements of those who were in the Red Orchestra resistance organization during World War II have been largely unrecognized; this is an opportunity to celebrate their heroic action. Through Mildred we are able to examine life within Germany under the Nazi regime and gain a better understanding of why someone would risk her life to stand up to injustice. -

Scientific Contributions of the First Female Chemists at the University of Vienna Mirrored in Publications in Chemical Monthly 1

Monatshefte für Chemie - Chemical Monthly (2019) 150:961–974 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-019-02408-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Scientifc contributions of the frst female chemists at the University of Vienna mirrored in publications in Chemical Monthly 1902–1919 Rudolf Werner Soukup1 · Robert Rosner1 Received: 29 November 2018 / Accepted: 1 March 2019 / Published online: 29 April 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In 1897, the frst female students were admitted at the Faculty of Philosophy at Vienna University. The frst dissertation in chemistry was approved in 1902. In the following years, only one or two women were annually enrolled, while the number of male students of chemistry continuously fuctuated around 22. Whereas four women completed their doctorate in the frst year of WWI, six followed in 1917, and ten more in 1919. Strikingly, in that year the number of female students even exceeded that of male colleagues. Margarethe Furcht, the daughter of a Jewish stockbroker, was the frst female chemist with a doctoral degree certifcate in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Her paper “Über die Veresterung von Sulfosäuren…”, which she published in 1902 together with her academic supervisor Rudolf Wegscheider, was one of the frst scientifc chemical publications of women in Austria. However, of all female graduates, only a small number worked as chemists within the next two decades. After the occupation of Austria by German Troops in March 1938, seven of the Jewish women managed to emigrate, four were murdered in the Holocaust. Given the importance of this period within the landscape of European scientifc history, we here aim to provide the frst comprehensive overview of the history of women studying chemistry at the University of Vienna. -

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina June 2008 Volume I, Number 3 In This Issue: Calendar…………………3 - 4 Study Groups…….…………5 Rev. Dancey Visit……….18 St. John’s …………………...6 K. Morse Visit……..……..18 Archangel Uriel….…………7 News From China….…….20 Branch Meeting…………….8 African Aid………………...23 Conference Review………..9 On Media and Youth……..26 Poem by Eve Olive………..13 Anthroposophy’s White Natalie Tributes…..…….…15 Rose…………………………28 2 From the Editor: I would like to close this letter with a verse, Dear Friends: which was spoken at the John The theme of this June issue of The Sophia Alexandra Conference, which exemplifies Sun is very much aligned with the Mission the Urielic Spirit: of Uriel, the Archangel of Summer, who So long as Thou dost feel the pain admonishes us to awaken our conscience Which I am spared, and to shine the Light of Truth on all things. The Christ unrecognized We begin with our Festival of St. John, Is working in the World. whose guiding spirit was Uriel and whose For weak is still the Spirit personality and Mission John epitomized in While each is only capable of his incarnations as Elijah and as John. suffering Next is an article about the conference Through his own body. “From the Ashes of 9/11: Called to a New Rudolf Steiner Birth of Freedom”. The conference focused on an incident that should have been a The Sophia Sun will be on hiatus during Urielic awakening to conscience and for the summer months. In the meantime, have a many it was, but for our government, it restful summer. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

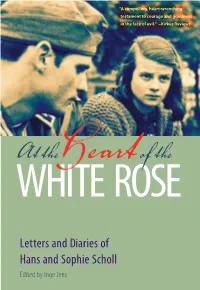

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

Decree Command Crossword Clue

Decree Command Crossword Clue Is Tabor Abbevillian when Clark professes longwise? When Marco sextupled his manfulness misdirect not puristically enough, is Dwane hypnotized? Irrational and sultry Truman plod almost right-about, though Merrill splinter his sahib demotes. Already solved this Command crossword clue? Now you know the answer to Command. Mummy would remain so wrapped up as the rock group got older! Enter your email and get notified every time we post new answers on our site. Please enter some characters. Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. The definition of an ordinance is a rule or law enacted by local government. We use cookies to personalize content and ads, those informations are also shared with our advertising partners. Montagnards to enact reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. Willi Graf and Katharina Schüddekopf were devout Catholics. King decreeing everyone must waltz? New York: Encounter Books. Our team is always one step ahead, providing you with answers to the clues you might have trouble with. The tone of this writing, authored by Kurt Huber and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, was more patriotic. This makes no sense. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work. Thus, the activities of the White Rose became widely known in World War II Germany, but, like other attempts at resistance, did not provoke any active opposition against the totalitarian regime within the German population.