These Are Raw Transcripts That Have Not Been Edited in Any Way, and May Contain Errors Introduced by the Volunteer Transcribers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

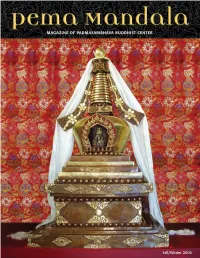

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Learn Tibetan & Study Buddhism

fpmt Mandala BLISSFUL RAYS OF THE MANDALA IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS JULY - SEPTEMBER 2012 TEACHING A GOOD HEART: FPMT REGISTERED TEACHERS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE FOUNDATION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE MAHAYANA TRADITION Wisdom Publications Delve into the heart of emptiness. INSIGHT INTO EMPTINESS Khensur Jampa Tegchok Edited by Thubten Chodron A former abbot of Sera Monastic University, Khensur Jampa Tegchok here unpacks with great erudi- tion Buddhism’s animating philosophical principle—the emptiness of all appearances. “Khensur Rinpoche Jampa Tegchok is renowned for his keen understanding of philosophy, and of Madhyamaka in particular. Here you will find vital points and reasoning for a clear understanding of emptiness.”—Lama Zopa Rinpoche, author of How to Be Happy 9781614290131 “This is one of the best introductions to the philosophy of emptiness 336 pages | $18.95 I have ever read.”—José Ignacio Cabezón, Dalai Lama Professor and eBook 9781614290223 Chair, Religious Studies Department, UC Santa Barbara Wisdom Essentials JOURNEY TO CERTAINTY The Quintessence of the Dzogchen View: An Exploration of Mipham’s Beacon of Certainty Anyen Rinpoche Translated and edited by Allison Choying Zangmo Approachable yet sophisticated, this book takes the reader on a gently guided tour of one of the most important texts Tibetan Buddhism has to offer. “Anyen Rinpoche flawlessly presents the reader with the unique perspective that belongs to a true scholar-yogi. A must-read for philosophers and practitioners.” —Erik Pema Kunsang, author of Wellsprings of the Great Perfection and 9781614290094 248 pages | $17.95 compiler of Blazing Splendor eBook 9781614290179 ESSENTIAL MIND TRAINING Thupten Jinpa “The clarity and raw power of these thousand-year-old teachings of the great Kadampa masters are astonishingly fresh.”—Buddhadharma “This volume can break new ground in bridging the ancient wisdom of Buddhism with the cutting-edge positive psychology of happiness.” —B. -

A Meeting with Drukpa Kagyu Masters

A Meeting with Drukpa Kagyu Masters Part I – In Honor of Geagen Khyentse and Amila Urgyen Chodon It was in the late summer of 1974 that I found myself on the road to the “Valley of the Gods” dangling from a bus as it weaved its way along the shoulders of a jagged Himalayan mountain road. Since the seats on the bus were quite small, I decided to hang a head and a shoulder outside the window from time to time. The fresh air felt good and made it worth it in spite of often having to veer down into the abyss to the river far below. The tires of our bus gripped the cliffs’ edges on uncertain gravel and, as if driven by a mad demon, the bus proceeded at a frantic pace trailed by a plume of cascading avalanches of pebbles and cobbles. Having just days earlier been in a bus accident near New Delhi, I imagined the worst would happen at every bump and turn on the way. I was on my way to Apho Rinpoche Gompa in Manali, Himachal Pradesh. Just a few days earlier I had arrived in India on a cheap Aeroflot flight from Moscow. On this leg of my journey, through unbelievable fortune, I met a young woman named Lin Lerner who was returning to India for the second time in pursuit of her dream to learn “Lama Dancing”, something traditionally reserved for men only. She connected me with the Kumar family who happened to be patrons of this Gompa. I was to learn that, most unfortunately, the great Drukpa Kagyu yogi Apho Rinpoche had passed on at a young age just a bit earlier that year. -

An Introduction to Tibetan Buddhist Canons

A Special SACHI Invitation to Members and Asian Art Museum Docents An Opportunity to Explore a Treasure Archive at Stanford The East Asia Library, Stanford recently acquired two monumental sets of Tibetan Buddhist canonical materials, the comparative editions of the Kanjur and Tanjur, which contain over four thousand Buddhist texts in the Tibetan language. To hear the in-depth story about the texts and this major acquisition, do not miss an incredible learning opportunity with Dr. Josh Capitanio of Stanford’s East Asia Library. In Conjunction with the Asian Art Museum Special Exhibition Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment SACHI Members and Asian Art Museum Docents are Invited to Join A Unique and Specially Designed Program on Stanford campus In this presentation, Dr. Josh An Introduction to Capitanio, Stanford Libraries’ subject specialist in Buddhism Tibetan Buddhist Canons and Asian religions, will give an introduction to the different Monday, March 30 textual canons of Tibetan Buddhism. Participants will 10:30 AM - 12:00 Noon learn about the significant role Stanford East Asia Library of canonical collections in the 518 Memorial Way, Room 224 history of Buddhism in Tibet, the different types of canons, and Please RSVP here the various methods used to For questions, please contact [email protected]; produce them. Several different Tel: 650-349-1247 examples of manuscripts and canonical texts from the Everyone is welcome to plan lunch after the event. A list of restaurant options in Stanford vicinity will be Stanford East Asia Library’s shared in a forthcoming announcement. collections will be on hand for participants to view. -

Rare and Important Manuscripts Found in Tibet

TIBETAN SCHOLARSHIP Rare and Important Manuscripts Found in Tibet By James Blumenthal he past few years has been an exciting time for scholars, Nyima Drak (b. 1055). Patsab Nyima Drak was the translator historians, and practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism as of Chandrakirti's writings into Tibetan and the individual Tdozens of forgotten and lost Buddhist manuscripts most responsible for the spread of the Prasangika- have been newly discovered in Tibet.' The majority of the Madhyamaka view in this early period. Included among this texts were discovered at Drepung monastery, outside of new discovery of Kadam writings are two of his original Lhasa, and at the Potala Palace, though there have been compositions: a commentary on Nagarjuna's Fundamental smaller groups of texts found elsewhere in the Tibet. The Wisdom of the Middle Way, and a commentary on Aryadeva's single greatest accumulation is the group of several hundred Four Hundred Stanzas on the Deeds of a Bodhisattva. Kadam texts dating from the eleventh to early fourteenth Perhaps the greatest Tibetan philosopher from this centuries that have been compiled and published in two sets period, and to this point, the missing link in scholarly under- of thirty pecha volumes (with another set of thirty due later standing of the historical development of Tibetan Buddhist this year). These include lojong (mind training) texts, thought was Chaba Chokyi Senge (1109-1169). This recent commentaries on a wide variety of Buddhist philosophical find produced sixteen previously lost or unknown texts by topics from Madhyamaka to pramana (valid knowledge) to Chaba including several important Madhyamaka and Buddha nature, and on cosmology, psychology and monastic pramana treatises. -

The Dark Red Amulet Dark Red Amulet.Qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page Ii Dark Red Amulet.Qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page Iii

Dark Red Amulet.qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page i The Dark Red Amulet Dark Red Amulet.qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page ii Dark Red Amulet.qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page iii The Dark Red Amulet ORAL INSTRUCTIONS ON THE PRACTICE OF VAJRAKILAYA by Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche and Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche Samye Translation Group Snow Lion Publications Ithaca, New York Dark Red Amulet.qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page iv SNOW LION PUBLICATIONS P. O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2008 Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche and Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche Previously published as a commentary by Dharma Samudra in 1992. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Text design by Rita Frizzell, Dakini Graphics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Palden Sherab, Khenchen, 1941- The dark red amulet : oral instructions on the practice of Vajrakilaya / Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche and Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-311-9 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-311-4 (alk. paper) 1. Vajraki-laya (Buddhist deity) I. Tsewang Dongyal, Khenpo, 1950- II. Title. BQ4890.V336P35 2008 294.3'444--dc22 2008020817 Dark Red Amulet.qxd:Final 12/3/08 5:40 PM Page v As with all Vajrayana practices, Vajrakilaya should not be practiced without receiving an empowerment or reading transmission directly from a qualified lineage master. -

"Tibet Has Come to Washington" DESTRUCTIVE EMOTIONS

Snow Lion Publications sv\LLionPO Box 6483, Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 Orders: 800-950-0313 ISSN 1059-3691 SUMMER 2000 NEWSLETTER Volume 15, Number 3 & CATALOG SUPPLEMENT "Tibet Has Come to Washington" DESTRUCTIVE EMOTIONS BY VICTORIA HUCKENPAHLER The Mind and Life Conference 2000 Sogyal Rinpoche comments on the Smithsonian Folklife Festival pro- BY VEN. THUBTEN CHODRON reason. Science sees emotions as gram, Tibetan Culture Beyond the Beginning in the mid-1980s, the having a physiological basis, and Land of Snows; the Ganden Tripa Mind and Life Institute has brought this raises further questions as to opens the first Great Prayer Festival together scientists from various fields human nature and the possibility of held in the West; H.H. Dalai Lama of expertise with His Holiness the pacifying destructive emotions. In addresses an audience of fifty thou- Dalai Lama in a series of confer- the West, emotions are important sand. ences. A theme is picked for each, for determining what is moral, and Under a turquoise sky, the living and five to seven scientists in that morality is essential for the function- mandala of Tibetan culture, which field are selected to make presen- ing of society. Thus working with was a highlight of this year's Smith- tations to His Holiness. These pre- emotions is seen as important for sonian Folklife Festival, spread itself sentations are given in the morning social interaction, not for having a over much of the National Mall, with session each day, and lively discus- good soul or being a good person. a variety of displays and activities sions among these key participants, This leads the West to focus on both sacred and secular. -

Vision of Samantabhadra - the Dzokchen Anthology of Rindzin Gödem

Vision of Samantabhadra - The Dzokchen Anthology of Rindzin Gödem Katarina Sylvia Turpeinen Helsinki, Finland M.A. University of Helsinki (2003) A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May 2015 Acknowledgements When I first came to the University of Virginia as a Ph.D. student in January 2005, I had no idea what journey had just started. During the course of my research, this journey took me to rigorous intellectual study and internal transformation, as well as leading me to explore Tibet and Nepal, and to more than four years of living in Tibetan religious communities in the Indian Himalayas. During my years of dissertation research, I was fortunate to meet a great array of bright, erudite, committed, kind, humble and spiritual minds, who have not only offered their help and inspiration, but also their deeply transformative example. I am particularly grateful to three individuals for their invaluable support in my dissertation project: Professor David Germano for his brilliant and patient guidance in all the stages of my research, Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche for his extraordinary insight and kindness in my contemplative training and Khenpo Nyima Döndrup for his friendship, untiring answers to my questions about Northern Treasures scriptures and generous guidance to Tibetan religious culture. In addition to Khenpo Nyima Döndrup, I am very grateful to have been able to study the texts of The Unimpeded Realization and The Self-Emergent Self-Arisen Primordial Purity with several other learned teachers: Khenpo Chöwang from Gonjang monastery in Sikkim, Khenpo Lha Tsering from the Nyingma Shedra in Sikkim, Khenpo Sönam Tashi from Dorjé Drak monastery in Shimla, Khenpo Chöying from the Khordong monastery in Kham and Lopön Ani Lhamo from the Namdroling monastery in Bylakuppe. -

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

KHYENTSE FOUNDATION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. Photo by Pawo Choyning Dorji. Aspiration Prayer Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292-1361), a great Tibetan master, wrote this prayer, which Rinpoche said we should recite as Khyentse Foundation’s aspiration: May I be reborn again and again, And in all my lives May I carry the weight of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings. And if I cannot bear that weight, At the very least, May I be born with the burden of thinking that the Buddhadharma may wane. 2 | KHYENTSE FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT KHYENTSE FOUNDATION’S ASPIRATION Excerpts from Rinpoche’s Address to the KF Board of Directors New York, October 22, 2016 irst of all, I have to rejoice about “As followers of Shakyamuni Buddha, what we have done. I think we the best thing that we can do is to pro- are supporting more than 2,500 tect and uphold his teachings, to keep monks and nuns and 1,500 lay them alive through studying and putting people, probably many more, them into practice.” helping all different lineages and traditions, not only — Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche the Tibetans. Khyentse Foundation has supported Fpeople from more than 40 different countries. We The longevity and the strength of the Dharma are so are also associated with 28 different universities. important because, if the Dharma becomes extinct, That is very worthy of rejoicing. then the source of the happiness, liberation, is fin- ished for all. Concern for the Dharma is bodhicitta. Of course, I don’t need to remind anyone that I don’t think there is any other greater bodhicitta Khyentse Foundation is not a materialistic, profit- — relative bodhicitta at least — than concern for oriented organization. -

The Art of Translating Tibetan

wisdom masterclass The Art of Translating Tibetan A WISDOM MASTERCLASS Thupten Jinpa on The Art of Translating Tibetan COURSE PACKET Produced in partnership with Tsadra Foundation Table of Contents 1. Introduction to Translation, Part 1 1 2. Introduction to Translation, Part 2 3 3. Translating Concepts and Terms: Reality, Part 1 9 4. Translating Concepts and Terms: Reality, Part 2 11 5. Getting Behind the Words with Gavin Kilty 13 6. Going Beyond Language and Translation as the Rebirth of the Text with Gavin Kilty 15 7. Literalism and Translating Terms with Gavin Kilty 16 8. The Responsibility of the Translator with Gavin Kilty 17 9. Translating Concepts and Terms: The Mind, Part 1 18 10. Translating Concepts and Terms: The Mind, Part 2 18 11. Group Workshop, Part 1 26 12. Group Workshop, Part 2 27 13. Group Workshop, Part 3 28 14. Group Workshop, Part 4 28 15. How Tibetan Texts Were Produced 31 16. The Use of Particles in Tibetan Texts 35 17. Translating Concepts and Terms: Meditation, Part 1 37 18. Translating Concepts and Terms: Meditation, Part 2 38 19. Best Practices with Wulstan Fletcher, Part 1 40 20. Best Practices with Wulstan Fletcher, Part 2 41 21. Best Practices with Wulstan Fletcher, Part 3 47 22. Introduction to Translating Verse 48 23. Verse Case Study #1: A Song of Milarepa 49 24. Verse Case Study #2: The Book of Kadam 51 25. Verse Case Study #3: A Poem of Tsongkhapa 54 The Art of Translating Tibetan, Wisdom Publications, Inc. © 2020 vi The Art of Translanting Tibetan 26. -

Translating the Words of the Buddha I Contents

Buddhist Literary Heritage Project Conference Proceedings Alex Trisoglio, Khyentse Foundation March 2009 March 2009 | Translating the Words of the Buddha i Contents Resolutions & Pledges Group Discussion ................................................................ 43 Breakout Groups on Community of Translators and Training Translators ..................................................... 46 Conference Resolutions............................................................ ii Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche.................................................. 50 Pledges ..................................................................................... iii Dzigar Kongtrül Rinpoche ................................................. 52 1. Introduction and Welcome 4. Leadership, Organisation, Next Steps Welcome: Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche................................... 1 Leadership ........................................................................... 54 Message from HH the 14th Dalai Lama (letter) ..................... 1 Organisational Structure ..................................................... 58 Remarks from HH Sakya Trizin (letter) ................................. 2 Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche Accepts Leadership Role . 60 Message from the late HH Mindrolling Trichen (letter) ....... 3 Message from Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche (video) .............. 61 Message from HH the 17th Karmapa (letter) ........................ 3 Tulku Pema Wangyal Rinpoche ........................................ 64 Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche ................................................ -

Dorjé Tarchin, the Mélong, and the Tibet Mirror Press: Negotiating Discourse on the Religious and the Secular Nicole Willock Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy & Religious Studies 5-2016 Dorjé Tarchin, the Mélong, and the Tibet Mirror Press: Negotiating Discourse on the Religious and the Secular Nicole Willock Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/philosophy_fac_pubs Part of the Asian History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Repository Citation Willock, Nicole, "Dorjé Tarchin, the Mélong, and the Tibet Mirror Press: Negotiating Discourse on the Religious and the Secular" (2016). Philosophy Faculty Publications. 34. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/philosophy_fac_pubs/34 Original Publication Citation Willock, N. (2016). Dorjé Tarchin, the Mélong, and the Tibet Mirror Press: Negotiating discourse on the religious and the secular. Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 36(1), 145-162. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol36/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy & Religious Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dorjé Tarchin, the Mélong, and the Tibet Mirror Press: Negotiating Discourse on the Religious and the Secular Nicole Willock Much scholarly attention has been gi en to the moving production away from the Buddhist- importance of the Mélong, the first Tibetan monastic elite, introducing a new genre into newspaper, in the discursive formation of Tibetan discourse, opening up a public sphere for Tibetan nationalism. Yet in claiming the Mélong Tibetans, and supporting vernacular language as ‘secular’ and ‘modern,’ previous scholarship has publications.