Rail Freight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian Free

FREE RAILFREIGHT IN COLOUR FOR THE MODELLER AND HISTORIAN PDF David Cable | 96 pages | 02 May 2009 | Ian Allan Publishing | 9780711033641 | English | Surrey, United Kingdom PDF Br Ac Electric Locomotives In Colour Download Book – Best File Book The book also includes a historical examination of the development of electric locomotives, allied to hundreds of color illustrations with detailed captions. An outstanding collection of photographs revealing the life and times of BR-liveried locomotives and rolling stock at a when they could be seen Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian across the network. The AL6 or Class 86 fleet of ac locomotives represents the BRB ' s second generation of main - line electric traction. After introduction of the various new business sectorsInterCity colours appeared in various guiseswith the ' Swallow ' livery being applied from Also in Cab superstructure — Light grey colour aluminium paint considered initially. The crest originally proposed was like that used on the AC electric locomotives then being deliveredbut whether of cast aluminium or a transfer is not quite International Railway Congress at Munich 60 years of age and over should be given the B. Multiple - aspect colour - light signalling has option of retiring on an adequate pension to Consideration had been given to AC Locomotive Group reports activity on various fronts in connection with its comprehensive collection of ac electric locos. Some of the production modelshoweverwill be 25 kV ac electric trains designed to work on BR ' s expanding electrified network. Headlight circuits for locomotives used in multiple - unit operation may be run through the end jumpers to a special selector switch remote Under the tower's jurisdiction are 4 color -light signals and subsidiary signals for Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian movements. -

The Role for Rail in Port-Based Container Freight Flows in Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by WestminsterResearch The role for rail in port-based container freight flows in Britain ALLAN WOODBURN Bionote Dr Allan Woodburn is a Senior Lecturer in the Transport Studies Group at the University of Westminster, London, NW1 5LS. He specialises in freight transport research and teaching, mainly related to operations, planning and policy and with a particular interest in rail freight. 1 The role for rail in port-based container freight flows in Britain ALLAN WOODBURN Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 20 7911 5000 Fax: +44 20 7911 5057 Abstract As supply chains become increasingly global and companies seek greater efficiencies, the importance of good, reliable land-based transport linkages to/from ports increases. This poses particular problems for the UK, with its high dependency on imported goods and congested ports and inland routes. It is conservatively estimated that container volumes through British ports will double over the next 20 years, adding to the existing problems. This paper investigates the potential for rail to become better integrated into port-based container flows, so as to increase its share of this market and contribute to a more sustainable mode split. The paper identifies the trends in container traffic through UK ports, establishes the role of rail within this market, and assesses the opportunities and threats facing rail in the future. The analysis combines published statistics and other information relating to container traffic and original research on the nature of the rail freight market, examining recent trends and future prospects. -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

(A) DB Cargo (UK) Limited Whose Registered Office Is at Lakeside Business Park, Carolina Way, Doncaster, South Yorkshire, DN4 5PN (“DBC”) (“The Claimant”); And

1 DETAILS OF PARTIES 1.1 The names and addresses of the parties to the reference are as follows; (a) DB Cargo (UK) Limited whose Registered Office is at Lakeside Business Park, Carolina Way, Doncaster, South Yorkshire, DN4 5PN (“DBC”) (“The Claimant”); and (b) Network Rail Infrastructure Limited whose Registered Office is at 1 Eversholt Street, London NW1 2DN (“Network Rail”) (“The Respondent”). (c) Contact details for DB Cargo: Graham White, Access Manager South, Lakeside Business Park, Carolina Way, Doncaster, South Yorkshire, DN4 5PN. (d) Contact details for Network Rail: Duncan Lovatt & Richard Hooper, Network Rail, Wales Route. 2 DETAILS OF REFERENCE 2.1 This matter is referred to a Timetable Panel (“the Panel”) for determination in accordance with Condition D5 of the Network Code 2.2 This Dispute arises from a decision of Network Rail in respect of Network Rail variations made pursuant to Condition D3.5 of the Network Code 3 CONTENTS OF REFERENCE This Sole Reference includes: - (a) The subject matter of the dispute in Section 4; (b) A detailed explanation of the issues in dispute in Section 5; (c) In Section 6, the decision sought from the panel in respect of legal entitlement. 4 SUBJECT MATTER OF DISPUTE 4.1 This dispute arises from the Late Notice Restrictions of Use between Stoke Gifford No 2/ Caldicot and Leckwith Loop North Jn from 0200 on Saturday 19th October to 0420 on Monday 21st October 2019. Possession Reference P2019/2680990 4.2 Copied and annexed to this Reference are: • Appendix A: DB Cargo (UK) Ltd response to 157-W30-WA19 (original) [Part] • Appendix B: Re-Issued request 157-W30-WA19 1 • Appendix C: DB Cargo (UK) Ltd response to 157-W30-WA19 (subsequent re-issue) [Part] • Appendix D: Decision document for Re-Issued request 157-WA30-WA19 [Part] • Appendix E: Works planned within the restriction of use. -

Surface Access Integrated Ticketing Report May 2018 1

SURFACE ACCESS INTEGRATED TICKETING REPORT MAY 2018 1. Contents 1. Executive Summary 3 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Methodology 3 1.3. Current Practice 4 1.4. Appetite and Desire 5 1.5. Barriers 5 1.6. Conclusions 6 2. Introduction 7 3. Methodology 8 4. Current Practice 9 4.1. Current Practice within the Aviation Sector in the UK 11 4.2. Experience from Other Modes in the UK 15 4.3. International Comparisons 20 5. Appetite and Desire 25 5.1. Industry Appetite Findings 25 5.2. Passenger Appetite Findings 26 5.3. Passenger Appetite Summary 30 6. Barriers 31 6.1. Commercial 32 6.2. Technological 33 6.3. Regulatory 34 6.4. Awareness 35 6.5. Cultural/Behavioural 36 7. Conclusions 37 8. Appendix 1 – About the Authors 39 9. Appendix 2 – Bibliography 40 10. Appendix 3 – Distribution & Integration Methods 43 PAGE 2 1. Executive Summary 1.1. Introduction This report examines air-to-surface access integrated ticketing in support of one of the Department for Transport’s (DfT) six policy objectives in the proposed new avia- tion strategy – “Helping the aviation industry work for its customers”. Integrated Ticketing is defined as the incorporation of one ticket that includes sur- face access to/from an airport and the airplane ticket itself using one transaction. Integrated ticketing may consider surface access journeys both to the origin airport and from the destination airport. We recognise that some of the methods of inte- grated ticketing might not be truly integrated (such as selling rail or coach tickets on board the flight), but such examples were included in the report to reflect that these exist and that the customer experience in purchasing is relatively seamless. -

High Speed Rail

House of Commons Transport Committee High Speed Rail Tenth Report of Session 2010–12 Volume III Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 24 May, 7, 14, 21 and 28 June, 12 July, 6, 7 and 13 September and 11 October 2011 Published on 8 November 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Transport Committee The Transport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Transport and its Associate Public Bodies. Current membership Mrs Louise Ellman (Labour/Co-operative, Liverpool Riverside) (Chair) Steve Baker (Conservative, Wycombe) Jim Dobbin (Labour/Co-operative, Heywood and Middleton) Mr Tom Harris (Labour, Glasgow South) Julie Hilling (Labour, Bolton West) Kwasi Kwarteng (Conservative, Spelthorne) Mr John Leech (Liberal Democrat, Manchester Withington) Paul Maynard (Conservative, Blackpool North and Cleveleys) Iain Stewart (Conservative, Milton Keynes South) Graham Stringer (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Julian Sturdy (Conservative, York Outer) The following were also members of the committee during the Parliament. Angie Bray (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Lilian Greenwood (Labour, Nottingham South) Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North) Gavin Shuker (Labour/Co-operative, Luton South) Angela Smith (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

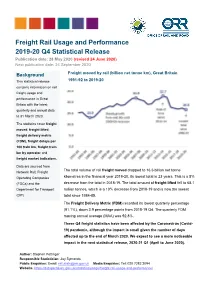

Freight Rail Usage and Performance 2019-20 Q4 Statistical Release Publication Date: 28 May 2020 (Revised 24 June 2020) Next Publication Date: 24 September 2020

Freight Rail Usage and Performance 2019-20 Q4 Statistical Release Publication date: 28 May 2020 (revised 24 June 2020) Next publication date: 24 September 2020 Freight moved by rail (billion net tonne km), Great Britain Background This statistical release 1991-92 to 2019-20 contains information on rail freight usage and performance in Great Britain with the latest quarterly and annual data to 31 March 2020. The statistics cover freight moved, freight lifted, freight delivery metric (FDM), freight delays per 100 train km, freight train km by operator and freight market indicators. Data are sourced from The total volume of rail dropped to 16.6 billion net tonne Network Rail, Freight freight moved Operating Companies kilometres in the financial year 2019-20, its lowest total in 23 years. This is a 5% (FOCs) and the decrease from the total in 2018-19. The total amount of freight lifted fell to 68.1 Department for Transport million tonnes, which is a 10% decrease from 2018-19 and is now the lowest (DfT). total since 1984-85. The Freight Delivery Metric (FDM) recorded its lowest quarterly percentage (91.1%), down 3.9 percentage points from 2018-19 Q4. The quarterly FDM moving annual average (MAA) was 92.8%. These Q4 freight statistics have been affected by the Coronavirus (Covid- 19) pandemic, although the impact is small given the number of days affected up to the end of March 2020. We expect to see a more noticeable impact in the next statistical release, 2020-21 Q1 (April to June 2020). Author: Stephen Pottinger Responsible Statistician: Jay Symonds Public Enquiries: Email: [email protected] Media Enquiries: Tel: 020 7282 2094 Website: https://dataportal.orr.gov.uk/statistics/usage/freight-rail-usage-and-performance/ 1. -

Network Rail Response with Appendices

Defendant’s Response to Sole Reference Ref: TTP1546 1 of 9 1 DETAILS OF PARTIES 1.1 The names and addresses of the parties to the reference are as follows:- (a) Freightliner Limited whose Registered Office is at 3rd Floor, 90 Whitfield Street, London W1T 4EZ (“Freightliner”) ("the Claimant"); and (b) Network Rail Infrastructure Limited whose Registered Office is at 1 Eversholt Street, London NW1 2DN ("Network Rail") ("the Defendant"). 1.2 Other Train and Freight Operating Companies that could be affected by the outcome of this dispute: (a) Greater Anglia (Abellio East Anglia Ltd), MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd, Arriva Rail London Ltd, GB Railfreight Ltd, DB Cargo (UK) Ltd, c2c (Trenitalia c2c Ltd) 2 CONTENTS OF THIS DOCUMENT This Response to the Claimant’s Sole Reference includes:- (a) Confirmation, or qualification, that the subject matter of the dispute is as set out by the Claimant in its Sole Reference, in the form of a summary schedule cross-referenced to the issues raised by the Claimant in the Sole Reference, identifying which the Defendant agrees with and which it disagrees with. (b) A detailed explanation of the Defendant’s arguments in support of its position on those issues where it disagrees with the Claimant’s Sole Reference, including references to documents or contractual provisions not dealt with in the Claimant’s Sole Reference. (c) Any further related issues not raised by the Claimant but which the Defendant considers fall to be determined as part of the dispute; (d) The decisions of principle sought from the Panel in respect of (i) legal entitlement, and (ii) remedies; (e) Appendices and other supporting material. -

Replacing Amtrak: Privatization, Regionalization, and Liquidation

P o l i c y S t u d y N o . 2 3 5 , O c t o b e r 1 9 9 7 RReeppllaacciinngg AAmmttrraakk:: A Blueprint for Sustainable Passenger Rail Service by Joseph Vranich EXECUTIVE SUMMARY mtrak is a failed national experiment. By its own admission, Amtrak is headed for bankruptcy unless Washington provides another multi-billion-dollar bail-out. Another federal rescue is A unjustified considering that federal and state subsidies to Amtrak since its inception in 1971 are nearing $22.5 billion, an amount out of proportion to Amtrak’s usefulness in most of the nation. The federal government does not run a national airline. It doesn’t operate a national bus company. There’s no justification for a national railroad passenger operation. America needs passenger trains in selected areas, but doesn’t need Amtrak’s antiquated route system, poor service, unreasonable operating deficits, and capital investment program with low rates of return. Amtrak’s failures result in part because it is a public monopoly—the very type of organization least able to innovate. This study reveals an Amtrak credibility crisis in the way it reports ridership figures, glosses over dwindling market share, understates subsidies, issues misleading cost-recovery claims, offers doubtful promises regarding high-speed rail, lacks proper authority for the freight business it recently launched, and misrepresents privatization as its applies to Amtrak. It’s time to liquidate Amtrak, privatize and regionalize parts of it, permit alternative operators to transform some long-distance trains into land-cruise trains, and stop service on hopeless routes. -

Eprints.Whiterose.Ac.Uk/2271

This is a repository copy of New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2271/ Monograph: Fowkes, A.S., Nash, C.A. and Tweddle, G. (1989) New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. Working Paper. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds , Leeds, UK. Working Paper 285 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Institute of Transport Studies University of Leeds This is an ITS Working Paper produced and published by the University of Leeds. ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. They represent only the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views or approval of the sponsors. White Rose Repository URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2271/ Published paper Fowkes, A.S., Nash, C.A., Tweddle, G. (1989) New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds. Working Paper 285 White Rose Consortium ePrints Repository [email protected] Working Paper 285 December 1989 NEW INTER-MODAL FREIGHT TECHNOLOGY AND COST COMPARISONS AS Fowkes CA Nash G Tweddle ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. -

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020 List of contents List of country abbreviations and regulatory bodies .................................................. 6 List of figures ............................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 9 2. Network characteristics of the railway market ........................................ 11 2.1. Total route length ..................................................................................................... 12 2.2. Electrified route length ............................................................................................. 12 2.3. High-speed route length ........................................................................................... 13 2.4. Main infrastructure manager’s share of route length .............................................. 14 2.5. Network usage intensity ........................................................................................... 15 3. Track access charges paid by railway undertakings for the Minimum Access Package .................................................................................................. 17 4. Railway undertakings and global rail traffic ............................................. 23 4.1. Railway undertakings ................................................................................................ 24 4.2. Total rail traffic ......................................................................................................... -

Fastline Simulation

(PRIVATE and not for Publication) F.S. 07131/5 fastline simulation FREIGHT STOCK PACK 03 VEA VANS INSTRUCTIONS FOR INSTALLATION AND USE OF A ROLLING STOCK PACK FOR TRAIN SIMULATOR 2015 This book is for the use of customers, and supersedes as from 13th July 2015, all previous instructions on the installation and use of the above rolling stock pack. THORNTON I. P. FREELY 13th July, 2015 MOVEMENTS MANAGER 1 ORDER OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 Installation ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 The Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 File Naming Overview.. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 File name options ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 History of the Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 Temporary Speed Restrictions. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 6 Scenarios ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Known Issues ..