Mock Begip 01 12 2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

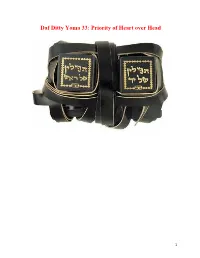

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart Over Head

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart over Head 1 2 3 § Abaye arranged the sequence of the daily services in the Temple based on tradition and in accordance with the opinion of Abba Shaul: Setting up the large arrangement of wood on the altar on which the offerings were burned precedes the second arrangement of wood. This second arrangement was arranged separately near the southwest corner of the altar, and twice every day priests raked coals from it and placed them on the inner altar in order to burn the incense. The second arrangement for the incense precedes setting up the two logs of wood above the large 4 arrangement to fulfill the mitzva of bringing wood. And the setting up of the two logs of wood precedes the removal of ashes from the inner altar. And the removal of ashes from the inner altar precedes the removal of ashes from five of the seven lamps of the candelabrum. And removal of ashes from five lamps precedes the slaughter and the receiving and sprinkling of the blood of the daily morning offering. The sprinkling of the blood of the daily offering 5 precedes the removal of ashes from the two remaining lamps of the candelabrum. And the removal of ashes from two lamps precedes the burning of the incense. The burning of the incense on the inner altar precedes the burning of the limbs of the daily offering on the outer altar. The burning of the limbs precedes the sacrifice of the meal-offering which accompanies the daily offering. -

The Decline of the Generations (Haazinu)

21 Sep 2020 – 3 Tishri 5781 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Haazinu The Decline of the Generations Introduction In this week’s Torah portion, Haazinu, Moses tells the Israelites to remember their people’s past: זְכֹר֙יְמֹ֣ות םעֹולָָ֔ ב ִּ֖ ינּו נ֣ שְ ֹותּדֹור־וָד֑ ֹור שְאַַ֤ ל אָב ֙יך֙ וְ יַגֵָ֔דְ ךזְקֵנ ִּ֖יך וְ יֹֹ֥אמְ רּו לְָָֽך Remember the days of old. Consider the years of generation after generation. Ask your father and he will inform you; your elders, and they will tell you. [Deut. 32:7] He then warns them that prosperity (growing “fat, thick and rotund”) and contact with idolaters will cause them to fall away from their faith, so they should keep alive their connection with their past. Yeridat HaDorot Strong rabbinic doctrine: Yeridat HaDorot – the decline of the generations. Successive generations are further and further away from the revelation at Sinai, and so their spirituality and ability to understand the Torah weakens steadily. Also, errors of transmission may have been introduced, especially considering a lot of the Law was oral: מש הק בֵלּתֹורָ ה מ סינַי, ּומְ סָרָ ּהל יהֹושֻׁעַ , ו יהֹושֻׁעַ ל זְקֵנים, ּוזְקֵנים ל נְב יאים, ּונְב יא ים מְ סָ רּוהָ ילְאַנְשֵ נכְ ס ת הַגְדֹולָה Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly. [Avot 1:1] The Mishnah mourns the Sages of ages past and the fact that they will never be replaced: When Rabbi Meir died, the composers of parables ceased. -

Daf Ditty Shekalim 14: Swept Away

Daf Ditty Shekalim 14: Swept Away The Death of Prince Leopold of Brunswick James Northcote (1746–1831) Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow Nephew of King Frederic II; from 1776 Regimentskommandeur und Stadtkommandant of Frankfurt (Oder); died tragically attempting to rescue some inhabitants of Frankfurt during the flood of 1785. 1 Halakha 2 · MISHNA There must be no fewer than seven trustees [amarkolin] and three treasurers appointed over the Temple administration. And we do not appoint an authority over the public comprised of fewer than two people, except for ben Aḥiyya, who was responsible for healing priests who suffered from intestinal disease, and Elazar, who was responsible for the weaving of the Temple curtains. The reason for these exceptions is that the majority of the public accepted these men upon themselves as officials who served without the assistance of even a single partner. 2 GEMARA: The mishna states that there must be no fewer three treasurers and seven trustees. The Gemara states that it was likewise taught in a baraita that there must be no fewer than two executive supervisors [katalikin]. This is as it is written in the verse that lists the men who supervised the receipt of teruma and tithes from the public and their distribution to the priests and the Levites, as well as the receipt of items dedicated to the Temple: And Jehiel, and Azaziah, and Nahath, and Asahel, and 13 גי ְָוֲַיﬠזזהוּ ִוִייחֵאל ְַוַנחתַ ַוֲﬠָשׂהֵאל Jerimoth, and Jozabad, and Eliel, and Ismachiah, and ְְִויַסְָמיכהוּ,ִִויירמוֹתְויָוָֹזבד, ֱֶוִאילֵאל ְְִויַסְָמיכהוּ, Mahath, and Benaiah, were overseers under the hand of מוּ ַ ַ ח ,ת בוּ ְ ָנ ָי וּה -- הו דיּמכונינ ,םַדִק ִִייְפּ ,םַדִק דיּמכונינ הו Conaniah and Shimei his brother, by the appointment of נָכּ( נַ יְ )וּהָ מִשְׁ ו ﬠְ יִ חָא ,ויִ מְ בּ פִ דַקְ חְ י זִ יִּקְ וּהָ וּהָ יִּקְ זִ חְ י דַקְ פִ מְ בּ ,ויִ חָא יִ ﬠְ מִשְׁ ו )וּהָ יְ נַ נָכּ( e,ֶ Hezekiah the king, and Azariah the ruler of the house ofֶלַהמּ ָוְּהיַרזֲַﬠו ידבְּגנ ֵיתִ - ִי.ֱםgהָהא God. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J. Berman Index More Information 231 Index Abbaye, 194 29a, 122n.122 Abramson, Shraga, 21n.24 , 114n.95 48b, 121n.121 Adam Chashuv , 120 , 152 , 171 , 186 71a, 22n.38 Agudah, 145n.13 8b, 121n.121 Agunah , 218 Albeck, Chanoch, 25n.52 , 40 , 120n.109 Batzri, Ezra, Rabbi, 203 Alon, Gedalyahu, 9n.18 , 178 Bava Batra Alter, Robert, 193 9a, 122n.122 Amalek , 195 , 211 10b, 122n.124 Amir, A.S., 22n.36 16b, 167n.77 Amital, Yehuda, Rabbi, 107n.77 45a, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Anas , 59 , 166 , 169 , 172 , 173 , 202 , 203 , 55a, 22n.38 206 , 208 173b, 22n.38 Arakhin Bava Kamma 16b, 106n.73 14b, 5n.8 19a, 122n.122 15a, 5n.8 Arkaot , 4 , 207 23b, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Aryeh Leib Hacohen Heller, 142n.3 55b, 14n.31 Asher ben Yechiel, 21n.25 , 42n.10 , 56a, 14n.31 60n.52 , 72 , 100n.47 , 128 , 129n.147 , 58b, 22n.38 131n.153 , 134n.157 , 153n.35 , 220 72b, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Ashi, 13 , 17 , 120 , 171 73a, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Atlas, Shmuel, 78n.1 80b, 12n.23 Auerbach, Shlomo Zalman, 202 81b, 126n.138 Avodah Zarah 88a, 5n.7 6a, 103n.61 92b, 42n.10 6b, 103n.61 112b, 155n.42 13a, 9n.15 , 12n.25 , 13n.28 113a, 111n.84 , 155n.42 13b, 12n.25 , 13n.27 , 13n.28 113b, 16 , 19n.19 , 70n.77 , 111n.84 , 19b, 19n.21 112n.90 20a, 112n.89 114a, 16 , 22n.35 , 70n.77 , 122n.123 26a, 22n.33 117a, 70 , 70n.80 28a, 121n.121 117b, 59n.51 231 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J. -

Aaron, 5–6, 39, 48, 56 Abba Sikrah, 59 Abbaye, 74 Abraham, Xi, Xii, 23

Index Aaron, 5–6, 39, 48, 56 Ben & Jerry’s, 157 Abba Sikrah, 59 Ben Azzai, 8, 10 Abbaye, 74 Ben Haim, Rabbi Eliahu, 109, Abraham, xi, xii, 23, 73, 121, 112, 164 141–142 Benhabib, Selya, 99, 103 Abramoff, Jack, 14, 163, 165, Berger, Michael, 167 167–168, 176, 198 Berkowitz, Rabbi Eliezer, 28, 46, Abtalion, 141 71, 73 accountability, 21, 38, 74, 79, 113, Bibi, Rabbi David, 112–113 158–159, 180, 184, 186, 192 Birnbaum, Philip, 12, 14, 24, 54, Ackerman, Bruce, 144, 145 65, 160, 161 Adam and Eve, 27, 161 Bloom, Stephen, 127 Adler, Rachel, 11, 24 Boaz, 12–14 Agriproccesors, 71, 76–79, 88, 119, Boesky, Ivan, 14 125–130, 132–134, 164 Bonder, Rabbi Nilton, 6, 8, 19, 24, Agudas Yisroel, 88 120, 135, 149, 155, 159, 161 Akiva, 8, 43, 53, 171–172, 196–198 Boulding, Kenneth, 156, 161 Allen, Rabbi Morris, 129, 192 Boyarin, Daniel, 11, 24 Allen, Woody, 4, 167 Brecht, Bertolt, 28 Alstott, Anne, 144, 145 Buber, Martin, xiv, 97, 103, 153, Amalek, 49 159, 179, 198 Amir, Yigal, 75–76, 117 Buchhholz, Rogene, 100, 103 Amos, 44 Annie Hall, 4 Caillois, Roger, 161 anti-Semitism, 110–112, 165, 173 Callahan, David, 93, 103 Ariel, Rabbi Yisrael, 20 capital punishment, 43, 155 Aron, Lewis, 24 Caro, Rabbi Yosef, 170 Carse, James, 92, 98–100, 103, Badaracco, Joseph, 4, 24 152, 157, 159, 161 Bal, Mieke, 11, 24 Carter, Stephen, 137, 145 Bar Illan University, 34 Cattle Buyers Weekly, 127 Bar Kochba, 43 Centrist Orthodoxy, 69–71 Bateson, Gregory, 161 chaos, xii, 124 Bathsheba, 102 chesed (kindness), 14, 141–142 202 Index Chofetz Chayim, 85, 89 Empire, 129 Choose life, 18, -

Humor in Talmud and Midrash

Tue 14, 21, 28 Apr 2015 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Jewish Community Center of Northern Virginia Adult Learning Institute Jewish Humor Through the Sages Contents Introduction Warning Humor in Tanach Humor in Talmud and Midrash Desire for accuracy Humor in the phrasing The A-Fortiori argument Stories of the rabbis Not for ladies The Jewish Sherlock Holmes Checks and balances Trying to fault the Torah Fervor Dreams Lying How many infractions? Conclusion Introduction -Not general presentation on Jewish humor: Just humor in Tanach, Talmud, Midrash, and other ancient Jewish sources. -Far from exhaustive. -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Talmud: Records teachings of more than 1,000 rabbis spanning 7 centuries (2nd BCE to 5th CE). Basis of all Jewish law. -Savoraim improved style in 6th-7th centuries CE. -Rabbis dream up hypothetical situations that are strange, farfetched, improbable, or even impossible. -To illustrate legal issues, entertain to make study less boring, and sharpen the mind with brainteasers. 1 -Going to extremes helps to understand difficult concepts. (E.g., Einstein's “thought experiments”.) -Some commentators say humor is not intentional: -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th century CE) always began his lectures with a joke: Before he began his lecture to the scholars, [Rabbah] used to say something funny, and the scholars were cheered. After that, he sat in awe and began the lecture. [Shabbat 30b] -Laughing and entertaining are important. Talmud: -Rabbi Beroka Hoza'ah often went to the marketplace at Be Lapat, where [the prophet] Elijah often appeared to him. -

Of Jewish Law?

Torah She’Be’Al Peh BeShanah History and Development of the Oral Tradition Class 10 – Codes and Codifiers Rabbi Moshe Davis Class Outline Review The Development of Halacha Changes in form and style vs. changes in substance Purpose of the Mishnah Torah I. Review The Jewish scholars between the 11th and 15th centuries are called the Rishonim. This is the first period in Jewish history where there is no longer one central location of Jewish life and learning. Small Jewish settlements across the Diaspora expand and become self sufficient both religiously and economically. The areas of scholarship for the Rishonim was very wide ranging, and for the most part, the Rishonim in Muslim controlled countries were more prolific writers and thinkers than those living in Christian countries. Why is there a need for a book (or one book) of Jewish Law? II. The Development of Halacha The short version 1. God gives Moshe the Torah at Mount Sinai but did not tell him everything explicitly – or at least it was not all explicitly recorded. 2. The sages of the next 1500 years expounded and expanded the Torah. 3. First with Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi’s Mishnah, followed by Ravina and Rav Ashi’s gemara, the Torah She’be’al Peh was organized and condensed. 4. The Rishonim did a bit of expanding themselves, but also organized and condensed the law. 5. Rav Yosef Cairo (and others) condensed the law. The long(er) version Moshe Received Torah at Sinai Written Torah Oral Torah Torah Neviim Ketuvim Non legal Law commentary on Philosophy Mystism written Torah Peirush -

Jewish Blood

Jewish Blood This book deals with the Jewish engagement with blood: animal and human, real and metaphorical. Concentrating on the meaning or significance of blood in Judaism, the book moves this highly controversial subject away from its traditional focus, exploring how Jews themselves engage with blood and its role in Jewish identity, ritual, and culture. With contributions from leading scholars in the field, the book brings together a wide range of perspectives and covers communities in ancient Israel, Europe, and America, as well as all major eras of Jewish history: biblical, talmudic, medieval, and modern. Providing historical, religious, and cultural examples ranging from the “Blood Libel” through to the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg, this volume explores the deep continuities in thought and practice related to blood. Moreover, it examines the continuities and discontinuities between Jewish and Christian ideas and practices related to blood, many of which extend into the modern, contemporary period. The chapters look at not only the Jewish and Christian interaction, but the interaction between Jews and the individual national communities to which they belong, including the complex appropriation and rejection of European ideas and images undertaken by some Zionists, and then by the State of Israel. This broad-ranging and multidisciplinary work will be of interest to students of Jewish Studies, History and Religion. Mitchell B. Hart is an associate professor of Jewish history at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He is the author of The Healthy Jew: The Symbiosis of Judaism and Modern Medicine (2007) and Social Science and the Politics of Modern Jewish Identity (2000). -

Vayeira Humbled Himself Before G-D in Saying, “I Am but Dust Furthermore, Abraham Was Not Afraid to Carry out This and Ashes” (Genesis 18:27)

THE DEEDS OF THE FATHERS ARE A SIGN FOR THE CHILDREN (BY RABBI DAVID HANANIA PInto SHLITA) is written, “For I have known him, in order This is why, among the ten trials that Abraham faced, that he may command his children and his none is described as a trial other than the one involving household after him, that they may observe Isaac, as it is written: “And G-d tried Abraham” (Genesis the way of the L-RD, to do righteousness 22:1). This is because Abraham did not sense the others and justice” (Genesis 18:19). as being trials, given that he was constantly performing IThis verset seems to indicate that the Holy One, blessed G-d’s will. When G-d told Abraham to offer his son as a be He, loved Abraham because he possessed the special burnt-offering, Abraham thought: “If I offer my son Isaac characteristic of “command[ing] his children and his household after him.” This is extraordinary, for Abra- as a burnt-offering, and he dies as a result, how will I be ham was a great tzaddik and possessed many virtues, able to teach my household the ways of Hashem? Be- especially chesed. This goes without mentioning the cause He commanded me, however, I will do so without fact that he overcame numerous trials and proclaimed arguing.” Since he overcame this trial, G-d said to him: Hashem’s Name to every wayfarer (Sotah 10b). He “Now I know that you fear G-d” (v.12). VAYEIRA humbled himself before G-d in saying, “I am but dust Furthermore, Abraham was not afraid to carry out this and ashes” (Genesis 18:27). -

PDF Study Guide#2 for Ethics of the Fathers

JUNE 1995 v"ba/ ztn/ 'c – ythx 'd VOLUME 16, No 6 /ttmnt vwt/ /tnab htkhgk Luach & Limud Personal Torah Study is dedicated in fond memory of its founder and first chairman Sander Kolitch k"z k"z vjna ketna w"c wsbx c"na/ tkxf 'd vwt/ lnt/ ,vwt/ cvte vwt/ yc ,vwt/ sntk A builder of Torah and Torah institutions whose dream of Luach & Limud has made daily Torah study a reality for thousands thwtgb /ae wfzkt Fritzi Kolitch k"z This prints on inside front cover v"g yvfv vhwe pxth /c edhhi d"ba/ ce v"f ltwc uwfz evh tswib ek u/tnct uvhhjc uhnhgbvt uhcvebv Published by ORTHODOX UNION Mandell I. Ganchrow, M.D., President Rabbi Raphael B. Butler, Executive Vice President Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, Senior Executive Orthodox Union National Limud Torah Commission Rabbi Sholom Rephun, Chairman Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Rothman, Vice Chairman Rabbi Jerry Willig, Vice Chairman Jeffrey Teitelbaum, Editor Acknowledgments: Luach Limud Personal Torah Study is an original concept for the presentation of Torah material, and incorporates the following. MISHNAH—A new translation of Mishnayot Mevuarot by Rabbi Pinhas Kehati published by the Department for Torah Education and Culture in the Diaspora of the World Zionist Organization — A product of the Kaplan Kushlick Foundation. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved. ADDITIONAL MATERIAL— Excerpts from the works of Rabbi Abraham Twerski, M.D. Reprinted with permis- sion of ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications Ltd. All rights reserved. LUACH—An original translation of the Calendar of Synagogue Customs, according to the Halachic decisions of Rabbi Yosef Eliyah Henkin, Zt”l, published by the Ezras Torah Fund. -

The Pirkei Avot Project

The Pirkei Avot Project A Communal Commentary on Pirkei Avot Written by members of Beth Sholom Congregation & Talmud Torah Shavuot 5780 / May 2020 Dedicated by Ellen & Marv Goldstein and Family בס’’ד ,Dear Friends We ask Hashem to .ותן חלקנו בתורתך :before the Shema אהבה רבה We read each day in the tefilah grant us a portion within the Torah. This communal commentary is exactly that - Beth Sholom’s portion in the Torah. We are all privileged to be part of a community that has prioritized Torah study in this way! May it be Hashem’s will that Beth Sholom continue to learn and study Torah together! -Rabbi Nissan Antine -Rabbi Eitan Cooper Shavuot 5780 Note: ❖ Some versions of Pirkei Avot differ in how they number each chapter and Mishnah. ❖ The English translation is provided by Dr. Joshua Kulp, from the Mishnah Yomit Archive found on www.sefaria.com. Thank you: Everyone who contributed Debra Band for cover art Judry Subar for editing Steven Lieberman for consulting Message from Ellen and Marv Goldstein & Family: We dedicate the Pirkei Avot Project to the Beth Sholom Community, who has enriched our lives with a love of learning and a deep connection to this community. (Goldstein family contributions to the commentary appear below): משנה אבות ד:יב ַרִבּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן שַׁמּוּעַ אוֹמֵ ר, יְהִי כְבוֹד תַּ לְמִידְ ָך חָבִיב עָלֶיָך כְּשֶׁ לְָּך, וּכְבוֹד ֲחֵבְרָך ְכָּמוֹרא ַרְבָּך, ָוּמוֹרא ַרְבָּך ְכָּמוֹרא שָׁמָ יִם: Pirkei Avot 4:12 Rabbi Elazar ben Shamua says: Let the honor of your student be dear to you as your own, and the honor of your fellow like the reverence of your teacher, and the reverence .. -

Moshevet Artzeinu Ekev

MOSHEVET ARTZEINU Menachem Av 22, 5781 - July 31, 2021 Ekev Parshat Ekev with Camp Rav Eliyahu Gateno In this week’s parasha, Moshe Rabbeinu speaks the land of Israel’s praises and mentions its special fruits – the famous shivat haminim through which Israel is lauded. “For the LORD your God is bringing you into a good land, a land with streams and springs and fountains issuing from plain and hill; a land Candle lighting of wheat and barley, of vines, gs, and pomegranates, a land of olive trees and honey; When you have 8:22PM (Camp Time 7:22PM) eaten your ll, give thanks to the LORD your God for the good land which He has given you.” The sages of the gemara argued about what beracha acharona is recited following the consumption Shabbos ends of one of the aforementioned seven species (Berachot 44a). In practice, we recite a beracha called 9:29PM (Camp Time 8:29PM) “me’ein shalosh”, a three-faceted blessing, in which we thank God specically for the shivat haminim. If we take a look at the dierent versions of this blessing, we notice that some versions lack the words “and we shall eat from its fruit, and be satiated from its goodness”, while others include them. The reason for this discrepancy is that there is an argument amongst the Rishonim as to whether these words need to be mentioned or not. The Ba’al Halachot Gedolot (a Rishon) holds that we shouldn’t say these words since it is not proper to love the Holy Land solely for the sake of its fruits, but rather for the fulllment of the mitzvot that are connected to it.