Gesher 4.1 1969.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parashat Ha'azinu 5774

Parashat Ha’azinu 5774 By Rachel Farbiarz September 7, 2013 This week’s Dvar Tzedek was originally published in 2009. “It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” ~William Carlos Williams (from “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower”) The Pentateuch’s penultimate portion, Parashat Ha’azinu, memorializes the “Song of Moses,” canted by the great leader on the day of his death. An epic poem in six parts, 1 Ha’azinu tells of God’s enduring relationship with Israel, unfurling their stormy entanglements into both desert past and prophetic future. Its recitation Moses’s last pedagogic act, the song-poem figures largely in the great leader’s final preparations for death. Moses schools the entire assembly in its verses, satisfying God’s command that Ha’azinu ’s words “not be forgotten from the mouths of your offspring.” And on the day of his death, the relentless scribe writes out the poem in its entirety, instructing the Levites that it be placed in the Sanctuary, next to the Ark of the Covenant. 2 There is powerful emotional force to this song-poem. Arranged not in the Torah’s typical textual format, Ha’azinu ’s verses instead are presented in columns—the better, one can imagine, to see their words quiver. Even our scrolls seem thus to acknowledge that Ha’azinu ’s power is drawn not from the narrative substance of its verses, but from their form; that the poem holds its audience in thrall through its couplets and cadences; its lurid imagery and outlandish metaphor; its esoteric language of “no-gods” and “no-folk.” 3 Ha’azinu ’s verses are less sentences than incantations—a kind of magic that does the heavy lifting of the soul from a posture of attention to one of rapture, from interest to commitment. -

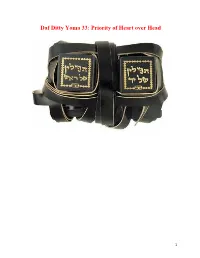

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart Over Head

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart over Head 1 2 3 § Abaye arranged the sequence of the daily services in the Temple based on tradition and in accordance with the opinion of Abba Shaul: Setting up the large arrangement of wood on the altar on which the offerings were burned precedes the second arrangement of wood. This second arrangement was arranged separately near the southwest corner of the altar, and twice every day priests raked coals from it and placed them on the inner altar in order to burn the incense. The second arrangement for the incense precedes setting up the two logs of wood above the large 4 arrangement to fulfill the mitzva of bringing wood. And the setting up of the two logs of wood precedes the removal of ashes from the inner altar. And the removal of ashes from the inner altar precedes the removal of ashes from five of the seven lamps of the candelabrum. And removal of ashes from five lamps precedes the slaughter and the receiving and sprinkling of the blood of the daily morning offering. The sprinkling of the blood of the daily offering 5 precedes the removal of ashes from the two remaining lamps of the candelabrum. And the removal of ashes from two lamps precedes the burning of the incense. The burning of the incense on the inner altar precedes the burning of the limbs of the daily offering on the outer altar. The burning of the limbs precedes the sacrifice of the meal-offering which accompanies the daily offering. -

A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2014 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Tobias Osterhaug Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Osterhaug, Tobias, "A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E." (2014). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 25. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/25 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Tobias Osterhaug History 499/Honors 402 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Introduction: The first Crusade, a massive and unprecedented undertaking in the western world, differed from the majority of subsequent crusades into the Holy Land in an important way: it contained no royalty and was undertaken with very little direct support from the ruling families of Western Europe. This aspect of the crusade led to the development of sophisticated hierarchies and vassalages among the knights who led the crusade. These relationships culminated in the formation of the Crusader States, Latin outposts in the Levant surrounded by Muslim states, and populated primarily by non-Catholic or non-Christian peoples. Despite the difficulties engendered by this situation, the Crusader States managed to maintain control over the Holy Land for much of the twelfth century, and, to a lesser degree, for several decades after the Fall of Jerusalem in 1187 to Saladin. -

Hebrew Printed Books and Manuscripts

HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. SELECTIONS FROM FROM THE THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, MARCH 30TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 51 Catalogue of HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS . SELECTIONS FROM THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON Sold by Order of the Trustees The Third Portion (With Additions) To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 30th March, 2004 (NOTE CHANGE OF SALE DATE) at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 28th March: 10 am–5:30 pm Monday, 29th March: 10 am–6 pm Tuesday, 30th March: 10 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our new Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Winnington” Sale Number Twenty Three. Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) Hebrew Index Available on Request KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 ¥ Tel: 212 366-1197 ¥ Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] ¥ World Wide Web Site: www.kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Belazel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale, please contact: Daniel E. -

Ubhztv and They Sing the Song of Moses, the Servant of G-D, and The

Kehilat Kol Simcha September 26, 2009 Gainesville, Florida ubhztv Shabbat T’Shuvah And they sing the Song of Moses, the servant of G-d, and the Song of the Lamb And they sing the Song of Moses, the servant of G-d, and the Song of the Lamb. Saying great, great and marvelous are your works, L-rd G-d Almighty. Just and true are your ways, L-rd, O King of the saints, who shall not fear you O L-rd? Hallelujah, Oh Hallelujah. (Integrity Hosanna Music) “9Remember the former things long past, For I am Elohim, and there is no other; I am Elohim, and there is no one like Me, 10Declaring the end from the beginning, And from ancient times things which have not been done, Saying, `My purpose will be established, And I will accomplish all My good pleasure.´” (Isa 46:9-10, NASB) “16vuvh said to Moshe, ‘You are about to sleep with your ancestors. But this people will get up and offer themselves as prostitutes to the foreign gods of the land where they are going. When they are with those gods, they will aban- don me and break my covenant which I have made with them…19Therefore, write this song for yourselves, and teach it to the people of Isra’el. Have them learn it by heart, so that this song can be a witness for me against the people of Isra’el.’” (Deut 31:16, 19 CJB) What is the last of the 613 mitzvot in the Torah? Here it is: “Therefore, write this song for yourselves, and teach it to the people of Isra’el. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

Family Tree Maker 2005

Stern and Löbl Family Genealogy Website - www.sternmail.co.uk/genealogy/ Name Name Birth location <Unnamed> Aida <Unnamed> Clara <Unnamed> Minna <Unnamed> Montoya ? Rosa ? ? Rabbi ? New York, USA ? Pauline ? ? Sarah ? ? Susie ? ? Tatiana ? ? Tina ? ? Walter ? ? Yael ? 1 Wife 1 3rd Thomas HERZ 3rd 3rd Charles WARREN 3rd Houston, TX, USA ABEL Marga Susanna Susie WERTHEIM ABEL Cologne, Germany ABEL Siegfried ABEL Cologne, Germany ABELES Rosi ABELES Waltsch ABELES Sara ABELES Waltsch Abenheimer Ruth Abenheimer Abenheimer Karl Abenheimer Mannheim Abraham Abraham Abraham Abraham ABRAHAM Feist ABRAHAM Meudt, Germany ABRAHAM Fraidgem ABRAHAM Quirnbach, Germany ABRAHAM Harry ABRAHAM ABRAHAM Ruth Helen ABRAHAM San Fransisco, Calif. ABRAHAM Lisette ABRAHAM ABRAHAM Hertz ABRAHAM ABRAHAM Nathan ABRAHAM Brandoberndorf, Germany Abraham Roeschen Abraham ABRAHAMOV Adva ABRAHAMOV Kibbutz Yakum, Israel ABRAHAMS Jaqueline ABRAHAMS Glasgow ABRAME Bernard ABRAME ABRAME Smadar ABRAME Afula, Israel Abrams Ellen Abrams ACKERMAN Hannchen ACKERMAN ACKERMANN Emma ACKERMANN Wiesloch ACKERMANN Simon ACKERMANN ADAMKIEWICZ Else ADAMKIEWICZ ADAMKIEWICZ Hugo ADAMKIEWICZ Adanso Isabel Jabat Adanso Adelson Eugene Adelson Adelson Lorraine Adelson Adelson Robert Adelson Adelson Robert Adelson ADLER Anselm ADLER Adler Berta Adler ADLER Eva ADLER ADLER Jette ADLER Edelfingen ADLER Gale ADLER ADLER Joel ADLER Floehau Adler Max Adler Wurzburg ADLER Meta ADLER Urspringen, Germany ADLER Rebeka ADLER Arnetz Gr Adler Josef Adler Adler Richard Adler ADLER Ruth ADLER ADLER Selig ADLER -

Mock Begip 01 12 2015.Pdf

Tilburg University Het begrip 'Ruach Ra'a' in de rabbijnse responsliteratuur van na 1945 Mock, Leon Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Mock, L. (2015). Het begrip 'Ruach Ra'a' in de rabbijnse responsliteratuur van na 1945: Een casestudy in de relatie tussen kennis over de fysieke wereld en traditionele kennis. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. okt. 2021 Het begrip ‘Ruach Ra‘a’ in de rabbijnse responsaliteratuur van na 1945: een casestudy in de relatie tussen kennis over de fysieke wereld en traditionele kennis Proefschrift c ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op dinsdag 1 december 2015 om 14.15 door Leon Mock geboren op 11 augustus 1968 te Amsterdam. -

1 I. Introduction: the Following Essay Is Offered to the Dear Reader to Help

I. Introduction: The power point presentation offers a number of specific examples from Jewish Law, Jewish history, Biblical Exegesis, etc. to illustrate research strategies, techniques, and methodologies. The student can better learn how to conduct research using: (1) online catalogs of Judaica, (2) Judaica databases (i.e. Bar Ilan Responsa, Otzar HaHokmah, RAMBI , etc.], (3) digitized archival historical collections of Judaica (i.e. Cairo Geniza, JNUL illuminated Ketuboth, JTSA Wedding poems, etc.), (4) ebooks (i.e. HebrewBooks.org) and eReference Encyclopedias (i.e., Encyclopedia Talmudit via Bar Ilan, EJ, and JE), (5) Judaica websites (e.g., WebShas), (5) and some key print sources. The following essay is offered to the dear reader to help better understand the great gains we make as librarians by entering the online digital age, however at the same time still keeping in mind what we dare not loose in risking to liquidate the importance of our print collections and the types of Jewish learning innately and traditionally associate with the print medium. The paradox of this positioning on the vestibule of the cyber digital information age/revolution is formulated by my allusion to continental philosophies characterization of “The Question Concerning Technology” (Die Frage ueber Teknologie) in the phrase from Holderlin‟s poem, Patmos, cited by Heidegger: Wo die Gefahr ist wachst das Retende Auch!, Where the danger is there is also the saving power. II. Going Digital and Throwing out the print books? Critique of Cushing Academy’s liquidating print sources in the library and going automated totally digital online: Cushing Academy, a New England prep school, is one of the first schools in the country to abandon its books. -

The Messianic Pendulum

ISSUE #34 THE MESSIANIC 2018 PENDULUM SWINGING BETWEEN HOPE AND HURT: 135-2000 C.E. BY SIMON HAWTHORNE AN OLIVE PRESS RESEARCH PAPER Welcome to the Olive Press Research Paper – an occasional paper featuring articles that cover a wide spectrum of issues which relate to the ministry of CMJ. Articles are contributed by CMJ staf (past and present), also by Trustees, Representatives, CMJ Supporters or by interested parties. Articles do not necessarily portray CMJ’s standpoint on a particular issue but may be published on the premise that they allow a pertinent understanding to be added to any particular debate. Telephone: 01623 883960 E-mail: [email protected] Eagle Lodge, Hexgreave Hall Business Park, Farnsfeld, Notts NG22 8LS THE MESSIANIC PENDULUM SWINGING BETWEEN HOPE AND HURT: 135-2000 C.E. Yossi came excitedly in to his wife. “I’ve got a new job!” he announced. “Te villagers realised they have no one looking out for Messiah and they want me to do it full time.” His wife looked unimpressed. “What’s the pay like?” “Terrible.” “What about holiday pay?” “Can’t have a holiday.” “Ten why so excited?” “It’s a permanent job!” Te story encapsulates the Jewish sense of hope and deferment which accompanies the Messianic Parousia. Jewish history is littered with hope and hurt, Claimants and Counterfeits. Only the notable were recorded for history. We will examine the infuence these had and how the hope they engendered often overwhelmed disappointment. We will the Messianic movements and the evolved understanding of the notion of Messiah within Judaism from Bar Kochba [135CE] to Schneerson [1902-1994]. -

No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: the Nineteenth-Century Jewish

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1997 No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot Mary A. Linderman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linderman, Mary A., "No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot" (1997). Dissertations. 3684. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3684 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1997 Mary A. Linderman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO "NO LONGER AN ALIEN, THE ENGLISH JEW": THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY JEWISH READER AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE JEW IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN DISRAELI, MATTHEW ARNOLD, AND GEORGE ELIOT VOLUME I (CHAPTERS I-VI) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY MARY A. LINDERMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 1997 Copyright by Mary A. Linderman, 1997 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the invaluable services of Dr. Micael Clarke as my dissertation director, and Dr. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J. Berman Index More Information 231 Index Abbaye, 194 29a, 122n.122 Abramson, Shraga, 21n.24 , 114n.95 48b, 121n.121 Adam Chashuv , 120 , 152 , 171 , 186 71a, 22n.38 Agudah, 145n.13 8b, 121n.121 Agunah , 218 Albeck, Chanoch, 25n.52 , 40 , 120n.109 Batzri, Ezra, Rabbi, 203 Alon, Gedalyahu, 9n.18 , 178 Bava Batra Alter, Robert, 193 9a, 122n.122 Amalek , 195 , 211 10b, 122n.124 Amir, A.S., 22n.36 16b, 167n.77 Amital, Yehuda, Rabbi, 107n.77 45a, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Anas , 59 , 166 , 169 , 172 , 173 , 202 , 203 , 55a, 22n.38 206 , 208 173b, 22n.38 Arakhin Bava Kamma 16b, 106n.73 14b, 5n.8 19a, 122n.122 15a, 5n.8 Arkaot , 4 , 207 23b, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Aryeh Leib Hacohen Heller, 142n.3 55b, 14n.31 Asher ben Yechiel, 21n.25 , 42n.10 , 56a, 14n.31 60n.52 , 72 , 100n.47 , 128 , 129n.147 , 58b, 22n.38 131n.153 , 134n.157 , 153n.35 , 220 72b, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Ashi, 13 , 17 , 120 , 171 73a, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Atlas, Shmuel, 78n.1 80b, 12n.23 Auerbach, Shlomo Zalman, 202 81b, 126n.138 Avodah Zarah 88a, 5n.7 6a, 103n.61 92b, 42n.10 6b, 103n.61 112b, 155n.42 13a, 9n.15 , 12n.25 , 13n.28 113a, 111n.84 , 155n.42 13b, 12n.25 , 13n.27 , 13n.28 113b, 16 , 19n.19 , 70n.77 , 111n.84 , 19b, 19n.21 112n.90 20a, 112n.89 114a, 16 , 22n.35 , 70n.77 , 122n.123 26a, 22n.33 117a, 70 , 70n.80 28a, 121n.121 117b, 59n.51 231 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J.