Of Jewish Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

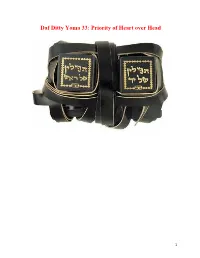

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart Over Head

Daf Ditty Yoma 33: Priority of Heart over Head 1 2 3 § Abaye arranged the sequence of the daily services in the Temple based on tradition and in accordance with the opinion of Abba Shaul: Setting up the large arrangement of wood on the altar on which the offerings were burned precedes the second arrangement of wood. This second arrangement was arranged separately near the southwest corner of the altar, and twice every day priests raked coals from it and placed them on the inner altar in order to burn the incense. The second arrangement for the incense precedes setting up the two logs of wood above the large 4 arrangement to fulfill the mitzva of bringing wood. And the setting up of the two logs of wood precedes the removal of ashes from the inner altar. And the removal of ashes from the inner altar precedes the removal of ashes from five of the seven lamps of the candelabrum. And removal of ashes from five lamps precedes the slaughter and the receiving and sprinkling of the blood of the daily morning offering. The sprinkling of the blood of the daily offering 5 precedes the removal of ashes from the two remaining lamps of the candelabrum. And the removal of ashes from two lamps precedes the burning of the incense. The burning of the incense on the inner altar precedes the burning of the limbs of the daily offering on the outer altar. The burning of the limbs precedes the sacrifice of the meal-offering which accompanies the daily offering. -

Mock Begip 01 12 2015.Pdf

Tilburg University Het begrip 'Ruach Ra'a' in de rabbijnse responsliteratuur van na 1945 Mock, Leon Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Mock, L. (2015). Het begrip 'Ruach Ra'a' in de rabbijnse responsliteratuur van na 1945: Een casestudy in de relatie tussen kennis over de fysieke wereld en traditionele kennis. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. okt. 2021 Het begrip ‘Ruach Ra‘a’ in de rabbijnse responsaliteratuur van na 1945: een casestudy in de relatie tussen kennis over de fysieke wereld en traditionele kennis Proefschrift c ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op dinsdag 1 december 2015 om 14.15 door Leon Mock geboren op 11 augustus 1968 te Amsterdam. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J. Berman Index More Information 231 Index Abbaye, 194 29a, 122n.122 Abramson, Shraga, 21n.24 , 114n.95 48b, 121n.121 Adam Chashuv , 120 , 152 , 171 , 186 71a, 22n.38 Agudah, 145n.13 8b, 121n.121 Agunah , 218 Albeck, Chanoch, 25n.52 , 40 , 120n.109 Batzri, Ezra, Rabbi, 203 Alon, Gedalyahu, 9n.18 , 178 Bava Batra Alter, Robert, 193 9a, 122n.122 Amalek , 195 , 211 10b, 122n.124 Amir, A.S., 22n.36 16b, 167n.77 Amital, Yehuda, Rabbi, 107n.77 45a, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Anas , 59 , 166 , 169 , 172 , 173 , 202 , 203 , 55a, 22n.38 206 , 208 173b, 22n.38 Arakhin Bava Kamma 16b, 106n.73 14b, 5n.8 19a, 122n.122 15a, 5n.8 Arkaot , 4 , 207 23b, 17n.3 , 19n.19 Aryeh Leib Hacohen Heller, 142n.3 55b, 14n.31 Asher ben Yechiel, 21n.25 , 42n.10 , 56a, 14n.31 60n.52 , 72 , 100n.47 , 128 , 129n.147 , 58b, 22n.38 131n.153 , 134n.157 , 153n.35 , 220 72b, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Ashi, 13 , 17 , 120 , 171 73a, 194n.14 , 194n.16 Atlas, Shmuel, 78n.1 80b, 12n.23 Auerbach, Shlomo Zalman, 202 81b, 126n.138 Avodah Zarah 88a, 5n.7 6a, 103n.61 92b, 42n.10 6b, 103n.61 112b, 155n.42 13a, 9n.15 , 12n.25 , 13n.28 113a, 111n.84 , 155n.42 13b, 12n.25 , 13n.27 , 13n.28 113b, 16 , 19n.19 , 70n.77 , 111n.84 , 19b, 19n.21 112n.90 20a, 112n.89 114a, 16 , 22n.35 , 70n.77 , 122n.123 26a, 22n.33 117a, 70 , 70n.80 28a, 121n.121 117b, 59n.51 231 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09065-1 — Boundaries of Loyalty Saul J. -

Jewish Blood

Jewish Blood This book deals with the Jewish engagement with blood: animal and human, real and metaphorical. Concentrating on the meaning or significance of blood in Judaism, the book moves this highly controversial subject away from its traditional focus, exploring how Jews themselves engage with blood and its role in Jewish identity, ritual, and culture. With contributions from leading scholars in the field, the book brings together a wide range of perspectives and covers communities in ancient Israel, Europe, and America, as well as all major eras of Jewish history: biblical, talmudic, medieval, and modern. Providing historical, religious, and cultural examples ranging from the “Blood Libel” through to the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg, this volume explores the deep continuities in thought and practice related to blood. Moreover, it examines the continuities and discontinuities between Jewish and Christian ideas and practices related to blood, many of which extend into the modern, contemporary period. The chapters look at not only the Jewish and Christian interaction, but the interaction between Jews and the individual national communities to which they belong, including the complex appropriation and rejection of European ideas and images undertaken by some Zionists, and then by the State of Israel. This broad-ranging and multidisciplinary work will be of interest to students of Jewish Studies, History and Religion. Mitchell B. Hart is an associate professor of Jewish history at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He is the author of The Healthy Jew: The Symbiosis of Judaism and Modern Medicine (2007) and Social Science and the Politics of Modern Jewish Identity (2000). -

Vayeira Humbled Himself Before G-D in Saying, “I Am but Dust Furthermore, Abraham Was Not Afraid to Carry out This and Ashes” (Genesis 18:27)

THE DEEDS OF THE FATHERS ARE A SIGN FOR THE CHILDREN (BY RABBI DAVID HANANIA PInto SHLITA) is written, “For I have known him, in order This is why, among the ten trials that Abraham faced, that he may command his children and his none is described as a trial other than the one involving household after him, that they may observe Isaac, as it is written: “And G-d tried Abraham” (Genesis the way of the L-RD, to do righteousness 22:1). This is because Abraham did not sense the others and justice” (Genesis 18:19). as being trials, given that he was constantly performing IThis verset seems to indicate that the Holy One, blessed G-d’s will. When G-d told Abraham to offer his son as a be He, loved Abraham because he possessed the special burnt-offering, Abraham thought: “If I offer my son Isaac characteristic of “command[ing] his children and his household after him.” This is extraordinary, for Abra- as a burnt-offering, and he dies as a result, how will I be ham was a great tzaddik and possessed many virtues, able to teach my household the ways of Hashem? Be- especially chesed. This goes without mentioning the cause He commanded me, however, I will do so without fact that he overcame numerous trials and proclaimed arguing.” Since he overcame this trial, G-d said to him: Hashem’s Name to every wayfarer (Sotah 10b). He “Now I know that you fear G-d” (v.12). VAYEIRA humbled himself before G-d in saying, “I am but dust Furthermore, Abraham was not afraid to carry out this and ashes” (Genesis 18:27). -

Moshevet Artzeinu Ekev

MOSHEVET ARTZEINU Menachem Av 22, 5781 - July 31, 2021 Ekev Parshat Ekev with Camp Rav Eliyahu Gateno In this week’s parasha, Moshe Rabbeinu speaks the land of Israel’s praises and mentions its special fruits – the famous shivat haminim through which Israel is lauded. “For the LORD your God is bringing you into a good land, a land with streams and springs and fountains issuing from plain and hill; a land Candle lighting of wheat and barley, of vines, gs, and pomegranates, a land of olive trees and honey; When you have 8:22PM (Camp Time 7:22PM) eaten your ll, give thanks to the LORD your God for the good land which He has given you.” The sages of the gemara argued about what beracha acharona is recited following the consumption Shabbos ends of one of the aforementioned seven species (Berachot 44a). In practice, we recite a beracha called 9:29PM (Camp Time 8:29PM) “me’ein shalosh”, a three-faceted blessing, in which we thank God specically for the shivat haminim. If we take a look at the dierent versions of this blessing, we notice that some versions lack the words “and we shall eat from its fruit, and be satiated from its goodness”, while others include them. The reason for this discrepancy is that there is an argument amongst the Rishonim as to whether these words need to be mentioned or not. The Ba’al Halachot Gedolot (a Rishon) holds that we shouldn’t say these words since it is not proper to love the Holy Land solely for the sake of its fruits, but rather for the fulllment of the mitzvot that are connected to it. -

THE 613 COMMANDMENTS by RABBI MENDEL WEINBACH

THE 613 COMMANDMENTS By RABBI MENDEL WEINBACH The Jew was given 613 commandments (mitzvot), according to the Talmud, which contain 248 positive commands and 365 negative ones. The positive mitzvot equal the number of parts of the body; the negative mitzvot correspond to the number of days in the solar year. Thus are we introduced to 613, the magic number of Torah scholarship and Jewish living. Its source is the Babylonian Talmud; its importance is echoed in a vast body of scholarly literature spanning a millennium; its potential as an aid to studying and remembering Torah deserves our careful analysis. The Talmud refers to this number as “taryag mitzvot.” Classical Jewish sources assign a numerical value to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, which is treated not as a mere utilitarian collection of word components but as a conveyor of esoteric information through the Kabbalistic medium of gematriya. Thus the gematriya (numerical equivalent) of taryag is 613 (tav = 400, raish = 200, yud = 10, and gimel = 3). The tradition of taryag mitzvot was developed by Rabbi Simlai of the Talmud, reasoning as follows: Scripture tells us that Moses commanded the Torah (Pentateuch) to the Children of Israel. The gematriya of the four Hebrew letters of the word Torah is 611. Add to this the two commandments which all of Israel heard from God Himself at Mt. Sinai and you have a total of 613 — taryag. Before any ambitious Bible student goes plunging into the five books of the Torah in search of a list of these commandments, he should be warned that the task is more formidable than it seems. -

Gesher 4.1 1969.Pdf

J l j t ~ l'i":l "The essence of our knowledge of the Deity is this: that He is One, the Creator and the Revealer of Commandments. And all the varied faculties of the spirit are only so many aids to the solution and the detailed description of this knowledge; their purpose is to clarify it and present it in a form that will be at once the most ideal, noble, rational, practical, simple and exalted ..." A Publication of "How shall man obtain a conception of the majesty of the G R Divine, so that the innate splendor residing within his soul may Student Organization of Yeshiva rise to the surface of consciousness, fully, freely, and without dis RABBI ISAAC ELCHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY tortion? Through the expansion of his scientific faculties; through the liberation of his imagination and the enjoyments of bold flights of thought; through the disciplined study of the world and of life; VOL. 4, NO. 1 ,~,w, m,,o, '::J through the cultivation of a rich, multifarious sensitivity to every phase of being. All these desiderata obviously require the study of all the branches of wisdom, all the philosophies of life, all the MENACHEM M . KASDAN, SIMON POSNER .... Editors ways of the diverse civilizations and the doctrines of ethics and MELVIN DAVIS, CARMI HOROWITZ .. Executive Editors religion in every nation and tongue. " NEIL LEIST . Managing Eaitor MOSHE FINE . Associate Editor RABBI ABRAHAM ISAAC Koo:< DAVID KLAVAN ..... ......... ... Assistant Editor HAROLD HOROWITZ, ALAN MOND, ........... ... ~¢®>1 ROBERT YOUNG Typing Editors YALE BUTLER, LAWREN CE LANGER, WILLIAM TABASKY . .. ................... Staff • Student Organization of Yeshiva ELIYAHU SAFRAN . -

The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, Volume IV Edited by Steven T

Cambridge University Press 0521772486 - The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, Volume IV Edited by Steven T. Katz Index More information INDEX 2 Baruch Abba bar Manayumi (Abba bar Martha) attitudes to the failure of the First Jewish (sage) 642 Revolt 31, 32 Abbahu, R. on the destruction of the Jerusalem on anti-Semitism in street theater in Temple 204 Caesaria 724 on Jewish uprisings 93 knowledge of Scripture 842 messianism 1061 on the neglect of the study of not christianized 249 Scripture 911 3 Baruch 59 on ridicule of Sabbath observance 147 Christian interpolations 249 on the sacrificization of prayer 585 4 Baruch, Christian interpolations 249 and the Tosefta 316 1 Clement, views on Judaism 253 on women’s education 917 2 Clement 65 Abramsky, R. Yeh.ezkel, commentary on the views on Judaism 252 Tosefta 333 4 Ezra Abudarham, David, on resurrection 963 anti-Judaism 264 academies 821 attitudes to the failure of the First Jewish Athens academy, closure by Justinian I the Revolt 31 Great 1047 Christian interpolations 249 and the creation of biographical on the destruction of the Jerusalem legends 727 Temple 204 cultural role 721, 722 on Jewish uprisings 93 curricula 912–13 messianism 1061 infestation by demons 733 Nahardea academy, foundation 19 Aaron, association with R. Ishmael b. Elisha, in Sura academy, foundation 19 Heikhalot literature 763 acceptance, concept 880, 888 Abaye acquital (kapparah ) 941 on conflict between midrash halachah Acts of Cyprian , The 73 and the legal demands of Acts of John 249 Scripture 359 Acts of Marian and James, The 73 on demonology 703, 731, 732, 733 Acts of Montanus and Lucius, The 73 mother Acts of Paul 251 aphorisms attributed to 704 Acts of Pilate 248 as informant about folk tales 724 Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs, The 73 on property rights 862 Adam, and Eve, marriage 619 Abba Arika, Rav 19, 88, 319, 738 Adan-Bayewitz, A. -

Halakha and Netiquette Dr. David Levy

Halakha and Netiquette Dr. David Levy Description: What does the Jewish tradition have to share with regards to questions concerning netiquette and online ethics? What is the relationship between the internet and civility? Has incivility in America increased due to social media and what are its effects on democratic public discourse? How can we measure the effects of online incivility by objective scientific criteria? Does online anonymity encourage harassment of women or does online anonymity protect marginalized groups? Why is cyberbullying a serious problem from the standpoint of Jewish ethics? How do we attempt to curb the epidemic of cyberbulling amongst students? How can schools and teachers take action to combat cyberbullying? What are the etiquette and ethics of social media? Does Facebook immorally lead to exploiting its users? What does Jewish law have to say about (1) responsible use of the internet? (2) causing harm psychologically of persons by "meanspeak", (3) embarassing person in public via the internet, (4) causing harm to individuals whereby a loshon ha-rah on the internet can kill a reputation or career opportunity or shidduch as per the criteria specified by the Chofetz Chaim's laws of considering one's words that can be used as a sword to harm or used to promote life, happiness, health, and constructive good? David B. Levy received a BA from Haverford College, an MA in Jewish Studies, an MLS from the UMCP, and a PhD from the BHU. David currently serves as a librarian at the Ruth Anne Hasten Library of Lander College for Women where David has prepared Judaica library guides on behalf of TC (found at http://libguides.tourolib.org/profile.php?uid=87838). -

The Karaite Halakah and Its Relation to Sadducean, Samaritan, And

THE KARAITE HALAKAH AND ITS RELATION TO SADDUCEAN, SAMARITAN AND PHILONIAN HALAKAH PART I BY BERNARD REVEL, M. A., PH. D. A THESIS SUBMITTED FEBRUARY 27, 1911 IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DROPSIE COLLEGE FOR HEBREW AND COGNATE LEARNING PHILADELPHIA 1913 PRESS OF CAHAN PRINTING CO , INC, PHILADELPHIA. PA , U. S. A. 1913 INQUIRY INTO THE SOURCES OF KARAITE HALAKAH THE causes of the Karaite schism and its early history are veiled in obscurity, as indeed are all the movements that originated in the Jewish world during the time be tween the conclusion of the Talmud Babli and the appear ance of Saadia Gaon. From the meager contemporary sources it would seem that from the second third of the eighth century untii the downfall of the Gaonate (1038) the whole intellectual activity of Babylonian Jewry centered about the two Academies and their heads, the Geonim. Of the early Gaonic period the Jewish literature that has reached us from Babylonia is mainly halakic in character, e. g. r Halakot Gedolot, Sheeltot, and works on liturgy, w hich afford us an insight into the religious life of the people. From them, however, we glean very little information about the inner life of the Jews in Babylonia before the rise of Karaism ; hence the difficulty of fully understanding the causes which brought about the rise of the only Jewish sect that has had a long existence and has affected the course of Jewish history by the opposition it has aroused. The study of sects always has a peculiar interest. -

Time Line of Jewish History with Rebbetzin Adina Landa

Chabad of Novato- Women’s Torah & Tea Time Line of Jewish History With Rebbetzin Adina Landa ▪ Creation of Heaven and Earth, and Adam and Eve ▪ The Forefathers ▪ Living in Egypt ▪ Traveling Through the Desert ▪ Judges and Early Prophets ▪ Kings and the First Holy Temple ▪ Exile in Babylon ▪ Building of the Second Holy Temple ▪ Greek Cultural Domination ▪ Kingdom of Judea: Dynasty of the Chashmona'im ▪ Roman Client Kings and Rulers: The Herodian Dynasty ▪ The Talmudic Era: The Mishnah ▪ The Talmudic Era: The Gemara ▪ The Rabbanan ▪ The Geonim ▪ The Early Rishonim: The Crusade Massacres ▪ Later Rishonim: Persecutions and Expulsions ▪ The Great Scholars of the Shulchan Aruch and Torah Consolidation ▪ Early Acharonim and East European Massacres ▪ Acharonim and Early Chassidim ▪ Later Acharonim and the Changing Society ▪ The Holocaust ▪ The Modern State of Israel Creation of Heaven and Earth, and Adam and Eve SECULAR YEAR JEWISH YEAR EVENT IN HISTORY -3760 1 Creation of the world; birth of Adam and Eve (Chavah) -3631 130 Seth (son of Adam) was born -3526 235 Enoch (son of Seth) was born -3436 325 Keynan (son of Enosh) was born -3366 395 Mehalalel (son of Keynan) was born -3301 460 Yered (son of Mehalalel) was born -3139 622 Chanoch (son of Yered) was born -3074 687 Metushelach (son of Chanoch) was born -2887 874 Lemech II (son of Metushelach) was born -2831 930 Adam died -2705 1056 Noah (son of Lemech II) was born -2225 1536 Noah began the construction of the ark -2205 1556 Yaphet (son of Noah) was born -2204 1557 Cham (son of Noah) was born