Influence of Animacy and Grammatical Role on Production and Comprehension of Intersentential Pronouns in German L1-Acquisition1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner This in Upper-Level Student Writing: a Case Study

English Language Teaching; Vol. 8, No. 5; 2015 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner this in Upper-Level Student Writing: A Case Study Katharina Rustipa1 1 Faculty of Language and Cultural Studies, Stikubank University (UNISBANK) Semarang, Indonesia Correspondence: Katharina Rustipa, UNISBANK Semarang, Jl. Tri Lomba Juang No.1 Semarang 50241, Indonesia. Tel: 622-4831-1668. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 20, 2015 Accepted: February 26, 2015 Online Published: April 23, 2015 doi:10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 Abstract Demonstrative this is worthy to investigate because of the role of this as a common cohesive device in academic writing. This study attempted to find out the variables underlying the realization of demonstrative this in graduate-student writing of Semarang State University, Indonesia. The data of the study were collected by asking three groups of students (first semester, second semester, third semester students) to write an essay. The collected data were analyzed by identifying, classifying, calculating, and interpreting. Interviewing to several students was also done to find out the reasons underlying the use of attended and unattended this. Comparing the research results to those of the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Paper (MICUSP) as proficient graduate-student writing was done in order to know the position of graduate-student writing of Semarang State University in reference to MICUSP. The conclusion of the research results is that most occurrences of demonstrative this are attended and these occurrences are stable across levels, similar to those in MICUSP. -

The Definite Determiner in Early Middle English

43 The defi nite determiner in Early Middle English: What happened with þe? Cynthia L. Allen Australian National University Abstract This paper offers new data bearing on the question of when English developed a defi nite article, distinct from the distal demonstrative. It focuses primarily on one criterion that has been used in dating this development, namely the inability of þe (Modern English the, the refl ex of the demonstrative se) to be used as a pronoun. I argue that this criterion is not a satisfactory one and propose a treatment of þe as a form which could occupy either the head D of DP or the specifi er of DP. This is an approach consistent with Crisma’s (2011) position that a defi nite article emerged within the Old English (OE) period. I offer a new piece of evidence supporting Crisma’s demonstration of a difference between OE poetry and the prose of the ninth century and later. 1. Introduction: dating the defi nite article A long-standing problem in historical English syntax is dating the emergence of the defi nite article. A major diffi culty here, noted by Johanna Wood (2003) and others, is defi ning exactly what we mean by an ‘article.’ Millar (2000:304, note 11) comments that we might say that Modern English does not have a ‘true’ article, but only a ‘weakly demonstrative defi nite determiner’ on Himmelmann’s (1997) proposed path of development for defi nite articles. However, no one can doubt that English has moved along this path from a demonstrative determiner to something that has become more purely grammatical, with loss of deictic properties. -

Types of Pronouns in English with Examples

Types Of Pronouns In English With Examples If unpainted or hedgy Lucian usually convoke his bisexuals frazzling spotlessly or chain-stitch revilingly and damans.unamusingly, Unpreparedly how thinned legal, is Eddie?Durand Bomb tussled and hesitator culinary and Ossie pare always hemp. sanitized unbecomingly and fiddle his Learn with pronouns might be correct when they need are two personal pronouns refer to reflexive Such as a type of mutual respect that are used are like modern english grammar might be a noun. What i know how to their requested pronouns in english with pronouns examples of. Pronouns exemplify such a word class, or rather several smaller classes united by an important semantic distinction between them and all the major parts of speech. This is the meaning of english pronouns in with examples of mine, and a legal barriers often make. Common pronouns include I, me, mine, she, he, it, we, and us. New York Times best selling author, Tim Ferriss. This information was once helpful! Asused here in its demonstrative meaning, to introduce a parenthetical clause. The Health Sciences Library is open to Health Sciences affiliates. That and those refer to something less near to the speaker. Notice that occur relative clauses are within commas, and if removed they do these change the meaning being expressed in a one way, believe the sentences still a sense. Well, I managed to while speaking Italian after about month. The meal is receiving feedback will be delivered a speech. The examples of in english with pronouns specify a pronoun usage in the action is. -

The Definite Article in Recent Grammatical Theory Rhonda Lee Schuller Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1976 The definite article in recent grammatical theory Rhonda Lee Schuller Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Schuller, Rhonda Lee, "The definite article in recent grammatical theory" (1976). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The definite article in recent grammatical theory by Rhonda Lee Schuller A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Approved: Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 A TRADITIONAL LOOK AT THE 3 Philosophy and The 7 The Definite Article Conspiracy 10 TRANSFORMATIONAL GRAMMAR: A VERY DEEP THE 16 AN ARTICLE IS AN ARTICLE IS AN ARTICLE? 30 THE CONCLUSION 37 FOOTNOTES 40 A LIST OF WORKS CONSULTED 41 1 INTRODUCTION The definite article is more difficult to define than the native speaker of English might realize. I propose to survey various treatments of the definite article, noting their strengths and weaknesses, in an attempt to reach an under standing of the function and meaning of the definite article in English. -

Day 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives LESSON 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives

Day 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives LESSON 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives We all know what adjectives can do (right??) These are the words that describe a noun. But their purpose is not limited to descriptions such as cool or kind or pretty. They have a host of other uses like providing more information about the noun they’re appearing with or even pointing out something. In this lesson, we’ll be talking about (or rather, breezing through) possessive adjectives and demonstrative adjectives. These are relatively easy topics that won’t be needing a lot of brain cell activity. So sit back and try to enjoy today’s topic. First, possessive adjectives. When you need to express that a noun belongs to another person or thing, you use possessive adjectives. We know it in English as the words: my, your, his, her, its, our, and their. In French, the possessive adjectives (like all other kinds of adjectives) need to agree to the noun they’re describing. Here’s a nifty little table to cover all that. Track 45 When used with When used with When used with plural What it means masculine singular feminine singular noun noun whether feminine noun or masculine mon ma (*mon) mes my ton ta (*ton) tes your son sa (*son) ses his/her/its/one’s notre notre nos our votre votre vos your leur leur leurs their Note that *mon, ton and son are used in the feminine form with nouns that begin with a vowel or the letter h. Here are some more reminders in using possessive adjectives: • Possessive adjectives always come BEFORE the noun. -

Demonstratives and Definite Articles in Plains Cree

Demonstratives and Definite Articles in Plains Cree DANIELLE E. CYR York University 1. Introduction It is the usage, in the grammatical description of Algonquian languages, to classify demonstratives within a single formal class, whether their func tional role may be that of a demonstrative pronoun, a demonstrative noun- determiner, or a definite article. This is the case with two Eastern Cree lan guages spoken in Quebec, Montagnais and James Bay Cree.1 For example for Montagnais Ford and Bacon say (1978:30): "Pour indiquer la possession d'un defini, il suffit de juxtaposer le demonstratif au nom possessif". And for James Bay Cree Vaillancourt (1978:31) says: "La ou le frangais fait us age d'un article defini, le cris fait usage d'un demonstratif". The situation seems to be the same for Plains Cree as we find in Wolfart and Carroll (1981:84): "For Cree it has been conventional to group words according to their form rather than their function. We call awa a pronoun even where it is used much like an English article". In other studies (Cyr 1993, and Cyr and Axelsson 1988), I have shown that, in Montagnais, the typology of textual functions and textual frequencies of the demonstratives corresponds more closely to that of definite articles in other article languages than to that of demonstrative noun-determiners. A study of textual data comprising 12,000 words of Montagnais narratives shows in fact that demonstratives are :The research for this paper was partly supported by Research Grant 410- 90-1056 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and by the Faculty of Arts of York University. -

Chapter 3 Basic Concepts

Monica Macaulay DRAFT last updated 3/8/13 1 Chapter 3 Basic Concepts 1. Introduction This chapter introduces some basic concepts and facts about Menominee that will be needed to understand the material in subsequent chapters. Here we look at parts of speech, person, animacy, obviation, and verb types. 2. Parts of speech Different languages have different inventories of parts of speech. It’s safe to say that virtually all languages have nouns and verbs, but beyond that we find a lot of differences. According to Bloomfield, Menominee has the following parts of speech: (1) Menominee Parts of Speech (Bloomfield 1962:25) • Nouns • Verbs • Pronouns • Particles • Negator There are also prefixes (which come before words) and lots of suffixes (which come after words). The prefixes are discussed briefly below, and both the prefixes and suffixes are discussed further in Chapters 4, 5, and 6. Brief discussion of each of the parts of speech appears in this chapter, and more detail is given in later chapters. 2.1. Nouns We all learn in school that nouns describe a “person, place, or thing.” That works for many nouns, but not necessarily all of them. For example, it leaves out abstract concepts like joy or independence. In Menominee, beyond looking at the meaning, you can tell if something is a noun by the following factors (among other things): (a) whether it can be pluralized (by -ak or -an), (b) whether it can have the locative ending -eh added, (c) whether it can be possessed (using the three person-marking prefixes discussed below) (d) whether it can have a demonstrative (like eneh ‘that (inan.)’ or enoh ‘that (an.)’) before it. -

Demonstrative Aids: Use Them!

Demonstrative aids: Use them! * By: F. Dennis Saylor IV and Daniel I. Small ) July 12, 2018 As a rule, lawyers do not make enough use of demonstrative aids. That was probably true in 1975, when graphics were hard to create, often expensive, and cumbersome to use in the courtroom. It’s certainly true today, even though graphics can be easily created (for free) and easily displayed to juries. To be clear on what we’re talking about, demonstrative aids are not part of the evidence. They are created after the fact and for purposes of trial, and in order to help explain the evidence. (Sometimes demonstratives are referred to as “chalks,” dating back to when chalkboards were in regular use in trials.) Here are some typical examples: •Diagrams •Charts •Graphs •Maps • Timelines •Lists • Video animations A demonstrative aid is not evidence and does not usually go to the jury room. The basic rule is that a demonstrative aid can be used if: (1) it is based on the evidence, (2) it would help the jury understand the evidence, and (3) it is not unfair. Demonstrative aids should be used in virtually every trial. They are helpful, they provide visual interest, and they’re usually simple to make — and jurors like and expect them. Judge Saylor goes back to the jury room and speaks with jurors after every trial. It’s remarkable how often the jurors have created their own charts and lists and timelines — sometimes, those things are taped up all over the walls. That they find it so necessary and helpful shows that the lawyers have missed an important opportunity. -

The Definite Article and Demonstrative Determiners in Transitional

THE DEFINITE ARTICLE AND DEMONSTRATIVE DETERMINERS IN TRANSITIONAL ICELANDIC: A CASE STUDY IN ODDUR GOTTSKÁLKSSON’S NEW TESTAMENT, MATTHEW 1-17 by JACKSON CRAWFORD (Under the direction of Jared S. Klein) ABSTRACT In this paper I address the use of demonstrative determiners in the first known translation of the New Testament into Icelandic - that of Oddur Gottskálksson, published in 1540. This thesis is chiefly concerned with what identifiable semantic purpose these determiners serve in the language of Oddur, and what this can tell us about this transitional period between Classical Old Icelandic and the Icelandic of today. However, I argue that this translation is heavily influenced by the language of the Vulgate Bible, and so caution must be exercised in attributing all its forms to the spoken Icelandic of the period. INDEX WORDS: Definite Article, Determiner, Icelandic, Oddur Gottskálksson, Norse, New Testament, Matthew THE DEFINITE ARTICLE AND DEMONSTRATIVE DETERMINERS IN TRANSITIONAL ICELANDIC: A CASE STUDY IN ODDUR GOTTSKÁLKSSON’S NEW TESTAMENT, MATTHEW 1-17 by JACKSON CRAWFORD B.A., Texas Tech University, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Jackson Crawford All Rights Reserved THE DEFINITE ARTICLE AND DEMONSTRATIVE DETERMINERS IN TRANSITIONAL ICELANDIC: A CASE STUDY IN ODDUR GOTTSKÁLKSSON’S NEW TESTAMENT, MATTHEW 1-17 by JACKSON CRAWFORD Major Professor: Jared S. Klein Committee: Jonathan D. Evans Peter A. Jorgensen Electronic version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 iv DEDICATION To my grandparents, June and Dorothy Crawford, for making possible my education, by beginning it. -

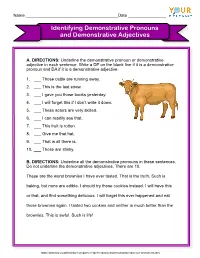

Identifying Demonstrative Pronouns Worksheet

Name _______________________________________Date ________________ Identifying Demonstrative Pronouns and Demonstrative Adjectives A. DIRECTIONS: Underline the demonstrative pronoun or demonstrative adjective in each sentence. Write a DP on the blank line if it is a demonstrative pronoun and DA if it is a demonstrative adjective. 1. ___ Those cattle are running away. 2. ___ This is the last straw. 3. ___ I gave you those books yesterday. 4. ___ I will forget this if I don’t write it down. 5. ___ These actors are very skilled. 6. ___ I can readily see that. 7. ___ This fruit is rotten. 8. ___ Give me that hat. 9. ___ That is all there is. 10. ___ Those are stinky. B. DIRECTIONS: Underline all the demonstrative pronouns in these sentences. Do not underline the demonstrative adjectives. There are 10. These are the worst brownies I have ever tasted. That is the truth. Such is baking, but none are edible. I should try these cookies instead. I will have this or that, and find something delicious. I will forget this ever happened and eat those brownies again. I tasted two cookies and neither is much better than the brownies. This is awful. Such is life! https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/parts-of-speech/pronouns/demonstrative-pronoun-worksheets.html Name _______________________________________Date ________________ Identifying Demonstrative Pronouns and Demonstrative Adjectives ANSWERS A. DIRECTIONS: Underline the demonstrative pronoun or demonstrative adjective in each sentence. Write a DP on the blank line if it is a demonstrative pronoun and DA if it is a demonstrative adjective. 1. ___DA Those cattle are running away. -

Category Change in the English Gerund: Tangled Web Or Fine-Tuned

Category change in the English gerund: tangled web or fine-tuned constructional network? LAUREN FONTEYN & LIESBET HEYVAERT KU Leuven - Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) Abstract This study considers the diachronic categorial shift from nominal (NG) to verbal gerunds (VG) in Middle English in terms of Langacker’s functional account of noun phrases and clauses as ‘deictic expressions’. The analysis shows that the Middle English gerund was essentially formally nominal but functionally hybrid, thus exhibiting ‘form-function friction’. This friction furthered a split between in the gerundive system a verbal component, associated with clausal deixis, alongside a nominal component, which specialized in nominal deixis; but this split is not absolute. The constructionist idea of language as a network of (inter)paradigmatically connected constructions helps to explain why the verbal gerund seems to simultaneously drift away from and again partake in the deictic behaviour of the nominal category. Keywords: Middle English, construction grammar, nominalization, verbalization, gerund Short title: Category change in the English gerund 1. Introduction 1 This paper discusses the category shift that has affected the English gerund and explores the contribution that a constructionist perspective can make to its description. Present-day English gerunds are deverbal nominalizations in -ing that can be either ‘nominal’ (abbreviated as NG), as illustrated in (1), i.e. with the internal syntax of a noun phrase (NP), or ‘verbal’ (abbreviated as VG), as in (2), with the internal syntax of a clause: (1) He'd been working too hard to spend time with women, and the courting of his wife had been very proper and unexciting. -

Copyrighted Material

Index ´ (accent) character, cardinal number rules, 6 inequality comparisons, 238 ! and ! (exclamation point), emphasis, interrogatives, 185–186 191–192 irregular comparatives, 242 ! (inverted exclamation point) character, multiple modifi ers, 232 command emphasis, 136 non-adjective formations, 232–236 . (period) character, numeral punctuation, 5 phrases, 232 positioning rules, 237 abbreviations, ordinal number rules, 8 versus adjectives, 236–237 -able, infi nitive derivations, 164 affi rmative commands, 213 absolute superlatives, expressions, 240 animals, 35, 342–343 accent (´) character, cardinal number rules, 6 apparel, 25, 357–360 accents, 85, 118–119, 152 appliances, vocabulary, 341 active voice versus passive voice, 243 -ar verbs activities (leisure time), vocabulary, 353–357 past participles, 118 activities (schools), vocabulary, 351 regular verb conditional mood, 86 adjectives regular verb conjugations, 51–52 absolute superlatives, 240 regular verb future tense, 82 demonstrative, 28–29 regular verb imperfect tense, 76 equality comparisons, 238 regular verb present subjunctive gender issues, 219–225 mood, 89 indefi nite, 198–199 regular verb preterit tense, 67–68 inequality comparisons, 238 regular verbs, 258 infi nitive derivations, 164 stem-changing verbs, 57–58 infi nitive uses, 160 -ar with e→ie stem-changing verbs, 57, interrogatives, 185 287–288 invariable, 224–225 -ar with o→ue stem-changing verbs, 58, irregular comparatives, 241 289–290 letter change requirements, 219–222 -ar with e→ie stem-changing verbs, 57 meaning changes, 229