Street Names, Political S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice-Guided Tour

ed guid Tou e- r ic o V isten 臺 北 Taipei Visitor Information Centers Taipei Main Station Add: 3, Beiping W. Rd., Taipei City (southwest area of Main Hall on 1F) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02) 2312-3256 Songshan Airport Add: 340-10, Dunhua N. Rd., Taipei City (Arrival Hall, Terminal 2) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2546-4741 MRT Taipei 101 / World Trade Center Add: B1, 20, Sec. 5, Xinyi Rd., Taipei City (near Exit No. 5) Station Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2758-6593 MRT Ximen Station Add: B1, 32-1, Baoqing Rd., Taipei City (near Exit No. 5) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2375-3096 MRT Jiantan Station Add: 65, Sec. 5, Zhongshan N. Rd., Taipei City (near Exit No. 1) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2883-0313 MRT Beitou Station Add: 1, Guangming Rd., Taipei City (left side of station entrance) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2894-6923 Miramar Entertainment Park Add: 20, Jingye 3rd Rd., Taipei City (at rear of fountain plaza, 1F) Visitor Center Tel: (02)8501-2762 Add: 6, Zhongshan Rd., Taipei City (near the Beitou Garden Spa) Plum Garden Visitor Center Tel: (02)2897-2647 Gondola Maokong Station Add: 35, Ln. 38, Sec. 3, Zhinan Rd., Taipei City Visitor Center (near exit of Maokong Station) Tel: (02)2937-8563 Add: 44, Sec. 1, Dihua St., Taipei City (inside URS44 Story House) Dadaocheng Visitor Center Tel: (02)2559-6802 MRT Longshan Temple Station Add: B1, 153, Sec. 1, Xiyuan Rd., Wanhua Dist., Taipei City (near Exit No. 1) Visitor Information Center Tel: (02)2302-5903 Travel Information Services Taipei Citizen Hotline: 1999 (outside Taipei City, please dial 02-2720-8889) Taipei Travel Net: www.travel.taipei/en, presents travel information on Taipei City in Chinese, English, Japanese and Korean; provides recorded-audio tour guide on related sightseeing spots, and a hotel information data base. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

Intermedialtranslation As Circulation

Journal of World Literature 5 (2020) 568–586 brill.com/jwl Intermedial Translation as Circulation Chu Tien-wen, Taiwan New Cinema, and Taiwan Literature Jessica Siu-yin Yeung soas University of London, London, UK [email protected] Abstract We generally believe that literature first circulates nationally and then scales up through translation and reception at an international level. In contrast, I argue that Taiwan literature first attained international acclaim through intermedial translation during the New Cinema period (1982–90) and was only then subsequently recognized nationally. These intermedial translations included not only adaptations of literature for film, but also collaborations between authors who acted as screenwriters and film- makers. The films resulting from these collaborations repositioned Taiwan as a mul- tilingual, multicultural and democratic nation. These shifts in media facilitated the circulation of these new narratives. Filmmakers could circumvent censorship at home and reach international audiences at Western film festivals. The international success ensured the wide circulation of these narratives in Taiwan. Keywords Taiwan – screenplay – film – allegory – cultural policy 1 Introduction We normally think of literature as circulating beyond the context in which it is written when it obtains national renown, which subsequently leads to interna- tional recognition through translation. In this article, I argue that the contem- porary Taiwanese writer, Chu Tien-wen (b. 1956)’s short stories and screenplays first attained international acclaim through the mode of intermedial transla- tion during the New Cinema period (1982–90) before they gained recognition © jessica siu-yin yeung, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00504005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded license. -

Pearl Lost in the Sea: Wan Jen, an Overlooked Director of the Taiwan New Cinema

《藝術學研究》 2009 年 12 月,第五期,頁 147-163 Pearl Lost in the Sea: Wan Jen, An Overlooked Director of the Taiwan New Cinema Chen, Ping-hao 陳平浩∗ Marking the dawn of a new era in Taiwan cinema, The Taste of Apple , the third installment of The Sandwich Man (1983), affirms Wan Jen's inclusion in the New Taiwan Cinema filmic movement. The film attests to significant differences between Wan Jen and his Taiwan contemporaries in addition to mapping out Wan Jen’s filmic concerns in his works from the 80s to the 90s. In this film Wan Jen brings Hou’s nostalgic villagers from the country to the city, and shows a working class view of the city tellingly different from Edward Yang’s bourgeois Taipei. “City vs. country conflict” is one of the dominant themes in Taiwan New Cinema. In the 70s, Taiwan’s economy took-off and earned the glorious label of the “Taiwan Miracle.” During these gilded years, Taiwan society underwent rapid industrialization, modernization, and urbanization. To make more money and earn a better life, lots of villagers “went north” in Taiwan, flocking to Taipei city with dreams of gold-digging. At the same time, the rural south’s traditional communities encountered the threat of urbanization and began to fall apart. Hou Hsiao-hsien’s autobiographical works in the 80s, especially A Time to Live, A Time to Die (1985) and Dust in the Wind (1986), express his nostalgia toward the (lost and imagined) “pre-modern Taiwan” in poetic forms. In stark contrast, Edward Yang’s modernist works, including ∗ M.A. -

Abstract Taiwanese Identity and Transnational Families

ABSTRACT TAIWANESE IDENTITY AND TRANSNATIONAL FAMILIES IN THE CINEMA OF ANG LEE Ting-Ting Chan, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Scott Balcerzak, Director This dissertation argues that acclaimed filmmaker Ang Lee should be regarded as a Taiwanese transnational filmmaker. Thus, to best understand his work, a Taiwanese sociopolitical context should be employed to consider his complicated national identity as it is reflected in his films across genres and cultures. Previous Ang Lee studies see him merely as a transnational Taiwanese-American or diasporic Chinese filmmaker and situate his works into a broader spectrum of either Asian-American culture or Chinese national cinema. In contrast, this dissertation argues his films are best understood through a direct reference to Taiwan’s history, politics, and society. The chapters examine eight of Lee’s films that best explain his Taiwanese national identity through different cultural considerations: Pushing Hands (1992) and Eat Drink Man Woman (1994) are about maternity; The Wedding Banquet (1993) and Brokeback Mountain (2005) consider homosexuality; The Ice Storm (1997) and Taking Woodstock (2009) represent a collective Taiwanese view of America; and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Lust, Caution (2007) reflect and challenge traditions of Taiwan Cinema. The eight films share three central leitmotifs: family, a sympathetic view of cultural outsiders, and a sympathy for the losing side. Through portraying various domestic relations, Lee presents archetypal families based in filial piety, yet at the same time also gives possible challenges represented by a modern era of equal rights, liberalism, and individualism – which confront traditional Taiwanese-Chinese family views. -

Read Book Following the Leader Ruling China, from Deng Xiaoping

FOLLOWING THE LEADER RULING CHINA, FROM DENG XIAOPING TO XI JINPING 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David M Lampton | 9780520281219 | | | | | Following the Leader Ruling China, from Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping 1st edition PDF Book Archived from the original on 11 July Following Mao's death on 9 September and the purge of the Gang of Four in October , Deng gradually emerged as the de facto leader of China. Deng and Liu's policies emphasized economics over ideological dogma, an implicit departure from the mass fervor of the Great Leap Forward. There was a significant amount of international reaction to Deng's death: UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said Deng was to be remembered "in the international community at large as a primary architect of China's modernization and dramatic economic development". Retrieved 22 July The Search for Modern China. Mao retained his status as a "great Marxist, proletarian revolutionary, militarist, and general", and the undisputed founder and pioneer of the country and the People's Liberation Army. Leaders of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. In Xi's view, the Communist Party is the legitimate, constitutionally-sanctioned ruling party of China, and that the party derives this legitimacy through advancing the Mao-style " mass line Campaign"; that is the party represents the interests of the overwhelming majority of ordinary people. His theoretical justification for allowing market forces was given as such:. In the 19th Party Congress held in , Xi reaffirmed six of the nine principles that had been affirmed continuously since the 16th Party Congress in , with the notable exception of "Placing hopes on the Taiwan people as a force to help bring about unification ". -

Mao's War on Women

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2019 Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 Al D. Roberts Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Al D., "Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976" (2019). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAO’S WAR ON WOMEN: THE PERPETUATION OF GENDER HIERARCHIES THROUGH YIN-YANG COSMOLOGY IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PROPAGANDA OF THE MAO ERA, 1949-1976 by Al D. Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Clayton Brown, Ph.D. Julia Gossard, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Li Guo, Ph.D. Dominic Sur, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________________________ Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 ii Copyright © Al D. Roberts 2019 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 by Al D. -

Title Does the Karate Kid Have a Kung Fu Dream? Hong Kong Martial Arts

Does the Karate Kid Have a Kung Fu Dream? Hong Kong Martial Title Arts between Hollywood and Beijing Author(s) Marchetti, G JOMEC Journal: Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, 2014, Citation n. 5 Issued Date 2014 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/204953 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License JOMEC Journal Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Does the Karate Kid Have a Kung Fu Dream? Hong Kong Martial Arts between Hollywood and Beijing Gina Marchetti University of Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Keywords The Karate Kid choreography wu shu movie fu real kung fu Abstract This analysis of the martial arts choreography in The Karate Kid (2010) examines the contradictory matrix in which action films produce meanings for global audiences. A remake of a 1984 film, this iteration of The Karate Kid begins its imaginative battle over martial arts turf with English and Chinese titles at odds with one another. For English- speaking audiences, the title of the film promises a remake of the popular 1984 story of a displaced Italian American teenager (Ralph Macchio) trained by a Japanese American sensei (Pat Morita) to compete against the local karate bullies. However, the 2010 version has another identity competing with the first. Its Chinese title translates as Kung Fu Dream – Japanese culture, karate, and domestic American class and racial politics out of the picture. In this version, an African American youngster (Jaden Smith) moves to Beijing from Detroit and is taken under the wing of a drunken kung fu master (Jackie Chan) to battle a group of wu shu/san da villains. -

Travel & Culture 2019

July 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 7 THE AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN TAIPEI IN OF COMMERCE THE AMERICAN CHAMBER TRAVEL & CULTURE 2019 TAIWAN BUSINESS TOPICS TAIWAN July 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 7 Vol. July 2019 | 中 華 郵 政 北 台 字 第 5000 號 執 照 登 記 為 雜 誌 交 寄 ISSUE SPONSOR Published by the American Chamber Of Read TOPICS Online at topics.amcham.com.tw NT$150 Commerce In Taipei 7_2019_Cover.indd 1 2019/7/3 上午5:53 CONTENTS 6 President’s View A few of my favorite Taiwan travel moments JULY 2019 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 7 By William Foreman 8 A Tour of Taipei’s Old Publisher Walled City William Foreman Much of what is now downtown Editor-in-Chief Taipei was once enclosed within Don Shapiro city walls, with access through Art Director/ / five gates. The area has a lot to Production Coordinator tell about the city’s history. Katia Chen By Scott Weaver Manager, Publications Sales & Marketing Caroline Lee 12 Good Clean Fun With Live Music in Taipei American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei Some suggestions on where to 129 MinSheng East Road, Section 3, go and the singers and bands 7F, Suite 706, Taipei 10596, Taiwan P.O. Box 17-277, Taipei, 10419 Taiwan you might hear. Tel: 2718-8226 Fax: 2718-8182 e-mail: [email protected] By Jim Klar website: http://www.amcham.com.tw 16 Taipei’s Coffee Craze 050 2718-8226 2718-8182 Specialty coffee shops have Taiwan Business TOPICS is a publication of the American sprung up on nearly every street Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC. -

Japan-Republic of China Relations Under US Hegemony: a Genealogy of ‘Returning Virtue for Malice’

Japan-Republic of China Relations under US Hegemony: A genealogy of ‘returning virtue for malice’ Joji Kijima Department of Politics and International Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2005 ProQuest Number: 10673194 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673194 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract Japan-Republic of China relations under US hegemony: A genealogy of ‘returning virtue for malice’ Much of Chiang Kai-shek’s ‘returning virtue for malice’ (yide baoyuan ) postwar Japan policy remains to be examined. This thesis mainly shows how the discourse of ‘returning virtue for malice’ facilitated Japan’s diplomatic recognition of the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan during the Cold War era. More conceptually, this study re- conceptualizes foreign policy as discourse—that of moral reciprocity—as it sheds light on the question of recognition as well as the consensual aspect of hegemony. By adopting a genealogical approach, this discourse analysis thus traces the descent and emergence of the ‘returning virtue for malice’ trope while it examines its discursive effect on Tokyo’s recognition of Taipei under American hegemony. -

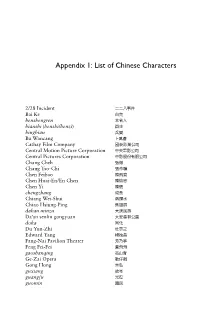

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios -

Midpacific Volume48 Issue2.Pdf

MID-PACIFIC MAGAZINE April-June, 1935 CONTENTS CHINA: 9 articles with 66 illustrations Today's China • KING-CHAD MUI, Consul-General for China in Hawaii My Glimpse of China R. F. LAMBERT. Member Association of Port Authorities Lingnon University FRANK S. WILSON, American Exchange Student. Dr. Sun Yat-sen's School Days in Hawaii PROF. SHAO CHANG LEE, University of Hawaii Painted Mask of the Chinese Stage GLADYS LI HEE, Student of Chinese Drama Chinese Foreign Study EDITORIAL on Tsing Hua University, Peiping China's Premier Agricultural College • ALEXANDER HUME FORD, Director Pan-Pacific Amazing Developments in China CAMERON FORBES, Leader American Economic Mission. Pon-Pacific Movement in China DR. KUANGSON YOUNG, Executive Secretary, Pan-Pacific Association Jane Addoms of Hull House (illustrate& ; Siam's Mongolia's mighty past I illustrated ) ; America's past and present (illus- new king (illustrated); Australia's aborigines lillustratecll ; Mexico's scientific explorations; Pelew Islands Canada, the last frontier 'illustrated ; Russia's trated); Honolulu's Pan - check list of fishes; Hawaii's Pan-Pacific Research Institution illustrated); and Occidental family life contrasted (illustrated) Japan's Pacific meeting programs; Japanese Pan-Pacific Clubs; Book Reviews of six recent publications. Published for the PAN-PACIFIC UNION, 1067 Alakeo Street HONOLULU, HAWAII $3.50 a Year 50c a Copy PAN-PACIFIC UNION 1067 Alakea Street, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. HON. WALTER F. FREAR, President HOWARD K. BURGESS, Treasurer DR. IGA MoRI, Vice-President WALTER F. DILLINGHAM, Chairman Finance C. K. At, Vice-President Committee ALEXANDER HUME FORD, Executive Director DR. FREDERICK G. KRAUSS, Chairman Pan- ANN Y.