The Route of Paul's Second Journey in Asia Minor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

TARİHSEL VE Mitolojikd) VERİLERİN IŞIĞINDA, DOĞU VE ORTA KARADENİZ BÖLGESİ UYGARLIKLARININ MADENCİLİK FAALİYETLERİ

Jeoloji Mühendisliği s. 39, 72-82, 1991 Geological Engineering,,, n. 39,72-82, 1991 TARİHSEL VE MİTOLOJİKd) VERİLERİN IŞIĞINDA, DOĞU VE ORTA KARADENİZ BÖLGESİ UYGARLIKLARININ MADENCİLİK FAALİYETLERİ Ahmet Hikmet KOSE Jeolqji Yüksek Mühendisi, TRABZON .A- GİRİŞ İL Neolitik Dönem. Yazıda ele alınan, bölge, yaklaşık olarak, 36°-42° Tarım ve hayvancılığın başladığı, keramiğin ve de- doğu boylamları ile 40°-42c" kuzey enlemleri arasında yer vamlı yerleşmelerin ortaya, çıktığı Neolitik, döneme. (MÖ almakta ve Doğu (ve Orta) Karadeniz coğrafi bölgesi ile 8.000-5,000) ait kalıntılardan bölgeye en yakın olan- Gürcistan Cumhuiiyetfnin bir bölümünü kapsamak- larına, Gürcistan. Cumhuriyeti'nde rastlanmıştır. Güney tadır. Osetia ve Merkezi Gürcistan'ın yanısıra Kolkhis'de^ de Bu bölge, ilk insanlardan günümüze, onlarca halka, Neolitik dönem, yerleşimi belirlenmiştir. bir o kadar da inanca, bazan anayurttuk, bazan da geçici bir konak yeri görevini üstlenen Küçük Asya'mın tümü III) Kalkolitik ve diğer maden dönemleri kadar olmasa bile, yine de çok sayıda halk ve uygarlığı bünyesinde barındırmıştır. Bu halklar ve madencilik faa- Samsung Amasya<4>, Tokat®, Ordu^, Sivas<7\ liyetleri üzerine yapılacak bir çalışmanın, ciltlerle ifade Erzincan^, Bayburt^, Erzurum<10\ Artvin ve Kars1'11) edilebilecek hacmi bir yana, genel bir özetinin bile bu illerinde. Kalkolitik dönemden (MÖ 5.000-3.000) derginin sınırlarını aşacak olması nedeniyle, bu yazıda, başlayan çeşitli izlere rastlanmıştır., yalnızca bazı konular ele alınarak, oldukça kısa bir Bu izler, küçük bir bölge söz konusu olmasına özetleme yapılmıştır, rağmen, tek bir kültüre ait değildir., Bölgenin batısında ele geçen buluntular "Orta Anadolu Kültürü"""' ile büyük B- İLK İNSANLARDAN BÖLGE benzerlik taşırken,, doğudakilerin, Transkafkasya-İran HALKLARINA AzerbaycanVDoğu Anadolu-Malatya ve Amik ovaları - Suriye ve İsrail'i" kapsayan bölge kültürü île ilişkili I- Paleolitik Dönem olduğu öne sürülmüştür. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen

Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Howard Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen This dissertation analyzes the three main protagonists of Lucan’s Bellum Civile through their attempts to utilize, resist, or match a pattern of action which I call the “formula.” Most evident in Caesar, the formula is a cycle of alternating states of energy that allows him to gain a decisive edge over his opponents by granting him the ability of perpetual regeneration. However, a similar dynamic is also found in rivers, which thus prove to be formidable adversaries of Caesar in their own right. Although neither Pompey nor Cato is able to draw on the Caesarian formula successfully, Lucan eventually associates them with the river-derived variant, thus granting them a measure of resistance (if only in the non-physical realm). By tracing the development of the formula throughout the epic, the dissertation provides a deeper understanding of the importance of natural forces in Lucan’s poem as well as the presence of an underlying drive that unites its fractured world. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................ vi Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Adalya 23 2020

ISSN 1301-2746 ADALYA 23 2020 ADALYA ADALYA 23 2020 23 2020 ISSN 1301-2746 ADALYA The Annual of the Koç University Suna & İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (OFFPRINT) AThe AnnualD of theA Koç UniversityLY Suna A& İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (AKMED) Adalya, a peer reviewed publication, is indexed in the A&HCI (Arts & Humanities Citation Index) and CC/A&H (Current Contents / Arts & Humanities) Adalya is also indexed in the Social Sciences and Humanities Database of TÜBİTAK/ULAKBİM TR index and EBSCO. Mode of publication Worldwide periodical Publisher certificate number 18318 ISSN 1301-2746 Publisher management Koç University Rumelifeneri Yolu, 34450 Sarıyer / İstanbul Publisher Umran Savaş İnan, President, on behalf of Koç University Editor-in-chief Oğuz Tekin Editors Tarkan Kahya and Arif Yacı English copyediting Mark Wilson Editorial Advisory Board (Members serve for a period of five years) Prof. Dr. Mustafa Adak, Akdeniz University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Engin Akyürek, Koç University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Nicholas D. Cahill, University of Wisconsin-Madison (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Edhem Eldem, Boğaziçi University / Collège de France (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Mehmet Özdoğan, Emeritus, Istanbul University (2016-2020) Prof. Dr. C. Brian Rose, University of Pennsylvania (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Charlotte Roueché, Emerita, King’s College London (2019-2023) Prof. Dr. Christof Schuler, DAI München (2017-2021) Prof. Dr. R. R. R. Smith, University of Oxford (2016-2020) © Koç University AKMED, 2020 Production Zero Production Ltd. Abdullah Sok. No. 17 Taksim 34433 İstanbul Tel: +90 (212) 244 75 21 • Fax: +90 (212) 244 32 09 [email protected]; www.zerobooksonline.com Printing Fotokitap Fotoğraf Ürünleri Paz. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

A Erosao, a Conservaçao E O Manejo Do Solo No Nordeste

SUDENE O.R.S.T.O.M. SUPERINTENDÊNCIA DO DESENVOLVIMENTO OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE DO NORDESTE SCIENTIFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE DEPART~ENTO DE RECURSOS NATURAlS OUTRE-MER DIVI~AO DE RECURSOS RENOVAVElS (FRANÇA) A EROSAO, A CONSERVAÇAO E 0 MANE]O DO SOLO NO NORDESTE BRASILEIRO BALANÇO, DIAGNOSTICO E NOVAS LINHAS DE PESQUISAS Jean-Claude LEPRUN Maître de Recherches Principal no ORSTOM Docteur ès Sciences Trabalho realizado mediante convênio SUDENE e ORSTOM Recife 1981 A EROsA01 A CONSERVAÇAO E 0 MANEJO DO SOLO NO NORDESTE BRASILEIRO , Balançol' diagnostico e novas linhas de pesquisas "É que 0 mal é antigo. Colaborando com os elementos meteorologicos, com 0 Nordeste, com a secçao das estradas, com as caniculas, com a erosao eolia, com as tempestades subitâneas. 0 ho mem fez-se um componente nefasto en tre as forças daquele clima demoli dor... Deu um auxiliar à degradaçao das tormentas... Fez, talvez, 0 de serto." (EUCLIDES DA CUNHA. Os Sertoes,l902). 3 SUMÂRIO APRESENTAÇAO 7 RESUMO 9 1 - SITUAÇAO DOS ESTUDOS DE CONSERVAÇAO E MANEJO DOS SOLO NO NORDESTE Il 1.1 - HIST5RICO .•..••...••..............•......•......•..•....•••• Il 1.2 - ESTUDOS E TRABALHOS JA REALIZADOS NO NORDESTE ...••••.••.•..• 12 1.3 - ESTUDOS EM ANDAMENTO •.•....•...•.•..••••.....•..••.•. ~ ...... 12 1.3.1 - Quadro - Caracteristicas fisicas e pesquisas desen- vo1vidas sobre conservaçâo e menejo dos solos no Nordeste (ate 0 fim do ano de 1980) atravês dos con- vênios 13 2 - A EQUAÇAO DE PERDAS DO SOLO DE WISCHMEIER •••..••.................. 19 2. 1 - INTRODUÇAO ....•.........•........•.......................•.. 19 2.2 - OS DIFERENTES FATORES DA EQUAÇAO ...•...•.•.•••............... 19 2.2.1 - 0 fator erosividade da chuva ou agressividade c1i- mâtica: R 19 2.2.1.1 - Tabe1a - Dados tirados do p1uviograma da chuva do dia 22/02/1969 em Gloria do Goita 20 2.2.1.2 - Fig. -

THE CHURCHES of GALATIA. PROFESSOR WM RAMSAY's Very

THE CHURCHES OF GALATIA. NOTES ON A REGENT CONTROVERSY. PROFESSOR W. M. RAMSAY'S very interesting and impor tant work on The Church in the Roman Empire has thrown much new light upon the record of St. Paul's missionary journeys in Asia Minor, and has revived a question which of late years had seemingly been set at rest for English students by the late Bishop Lightfoot's Essay on "The Churches of Galatia" in the Introduction to his Commen tary on the Epistle to the Galatians. The question, as there stated (p. 17), is whether the Churches mentioned in Galatians i. 2 are to be placed in "the comparatively small district occupied by the Gauls, Galatia properly so called, or the much larger territory in cluded in the Roman province of that name." Dr. Lightfoot, with admirable fairness, first points out in a very striking passage some of the " considerations in favour of the Roman province." " The term 'Galatia,' " he says, " in that case will comprise not only the towns of Derbe and Lystra, but also, it would seem, !conium and the Pisidian Antioch; and we shall then have in the narrative of St. Luke (Acts xiii. 14-xiv. 24) a full and detailed account of the founding of the Galatian Churches." " It must be confessed, too, that this view has much to recom mend it at first sight. The Apostle's account of his hearty and enthusiastic welcome by the Galatians as an angel of God (iv. 14), would have its counterpart in the impulsive warmth of the barbarians at Lystra, who would have sacri ficed to him, imagining that 'the gods had come down in VOL. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

Greek Cities & Islands of Asia Minor

MASTER NEGATIVE NO. 93-81605- Y MICROFILMED 1 993 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES/NEW YORK / as part of the "Foundations of Western Civilization Preservation Project'' Funded by the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES Reproductions may not be made without permission from Columbia University Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States - Title 17, United photocopies or States Code - concerns the making of other reproductions of copyrighted material. and Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries or other archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy the reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that for any photocopy or other reproduction is not to be "used purpose other than private study, scholarship, or for, or later uses, a research." If a user makes a request photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of fair infringement. use," that user may be liable for copyright a This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept fulfillment of the order copy order if, in its judgement, would involve violation of the copyright law. AUTHOR: VAUX, WILLIAM SANDYS WRIGHT TITLE: GREEK CITIES ISLANDS OF ASIA MINOR PLACE: LONDON DA TE: 1877 ' Master Negative # COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES PRESERVATION DEPARTMENT BIBLIOGRAPHIC MTCROFORM TAR^FT Original Material as Filmed - Existing Bibliographic Record m^m i» 884.7 !! V46 Vaux, V7aiion Sandys Wright, 1818-1885. ' Ancient history from the monuments. Greek cities I i and islands of Asia Minor, by W. S. W. Vaux... ' ,' London, Society for promoting Christian knowledce." ! 1877. 188. p. plate illus. 17 cm. ^iH2n KJ Restrictions on Use: TECHNICAL MICROFORM DATA i? FILM SIZE: 3 S'^y^/"^ REDUCTION IMAGE RATIO: J^/ PLACEMENT: lA UA) iB . -

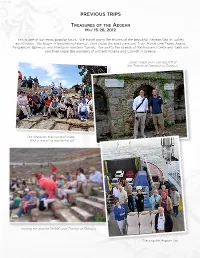

Previous Trips

PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Jacob Shock and Evan Bassett at the Temple of Domitian in Ephesus Our Group on the island of Crete – With a few of us wandering off Visiting the ancient 24,000 seat Theater at Ephesus Crossing the Aegean Sea PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Don and grandson Evan at Assos Mars Hill in Athens Well known archaeologist, Cingiz Icten, is pictured with Jacob Shock (left), guide Yeldiz Ergor, and Nancy and Don Bassett at the recently excavated Slope Houses in Ephesus Nancy and her brother Jack Woolf in Istanbul PREVIOUS TRIPS IN THE STEPS OF MOSES AND JOSHUA EGYPT, SINAI, JORDAN, ISRAEL MAY 5-20, 2010 This great tour began with visits to the Giza Pyramids, the Cairo Museum, and the amazing new Library of Alexandria. -

Numismata Graeca; Greek Coin-Types, Classified For

NUMISMATA GRAECA GREEK COIN-TYPES CLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFICATION PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTERS, MACON (fRANCb). NUMISMATA GRAEGA GREEK GOIN-TYPES GLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFICATION BY L^" CI flu pl-.M- ALTAR No. ALTAR Metal Xo. Pi.ACi: OBVEnSE Reverse V\t Denom . 1)a Pl.A Ri;it:iii;n(:i; SlZE II Nicaen. AVTKAINETPAIANOC. Large altar ready laid with /E.8 Tra- II un teriaii (]oll Jiilhijni:t. Ileadof Trajan r., laur. wood and havin^' door in 20 jan. p. 247, Xo 8. front; beneath AIOC. Ves- Prusiiis AYTKAilAPIIEBAI EniMAPKOYnAAN. P. I. R. .M. Pontus, etc, pasian, ad IIy])ium. TnOYEinAIIAN KIOYOY APOYAN- 22.5 12 p. 201, No 1. A. D. Billiynia. Headof Altar. nnPOYIIEII- eYHATOY. 200 Vespasian to r., laur. \:i .Aiiiasia. (]ara- 10, \o 31, AYKAIMAYP AAPCeYANTAMACIACM... , , p. Ponliirt. ANTnNINOC-Biislof in ex., eTCH. Altar of 1.2 caila. Caracalla r., laureale two stages. 30 A. n. in Paludamentum and 208 ciiirass. 14 l ariiini. Hust of Pallas r., in hel n A Garlanded altar, yE.5 H. C. R. M. Mysia, p. 1(11, Mijsiu. niet ; borderofdots. 12.5 P I 200 No 74. to Au- gus- tus. 15 Smyrna. TIB€PIOC C€BAC- ZMYPNAICON lonia. TOC- Ilead of Tibe- lePGONYMOC. Altar -ar- .E.65 Tibe- B. M. lonia, p. 268, rius r.,laur. landed. 10 No 263. 16 .\ntioch. BOYAH- Female bust ANTlOXenN- Altar. ^E.7 Babelon,/»^. Wadd., C.nria. r., veiled. 18 p. 116, \o 21.')9. 17 ANTIOXeWN cesAC CYNAPXiA AFAAOY .E.6 Au- ,, ,, No 2165. TOY- Nil^e staiiding. TOY AfAAOY. Altar, 15 gus- tus.