3 Political Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing

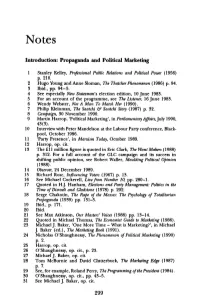

Notes Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing 2 Stanley Kelley, Professional Public Relations and Political Power (1956) p. 210. 2 Hugo Young and Anne Sloman, The Thatcher Phenomenon (1986) p. 94. 3 Ibid., pp. 94-5. 4 See especially New Statesman's election edition, 10 June 1983. 5 For an account of the programme, see The Listmer, 16 June 1983. 6 Wendy Webster, Not A Man To Matcll Her (1990). 7 Philip Kleinman, The Saatchi & Saatchi Story (1987) p. 32. 8 Campaign, 30 November 1990. 9 Martin Harrop, 'Political Marketing', in ParliamentaryAffairs,July 1990, 43(3). 10 Interview with Peter Mandelson at the Labour Party conference, Black- pool, October 1986. 11 'Party Presence', in Marxism Today, October 1989. 12 Harrop, op. cit. 13 The £11 million figure is quoted in Eric Clark, The Want Makers (1988) p. 312. For a full account of the GLC campaign and its success in shifting public opinion, see Robert Waller, Moulding Political Opinion (1988). 14 Obse1ver, 24 December 1989. 15 Richard Rose, Influencing Voters (1967) p. 13. 16 See Michael Cockerell, Live from Number 10, pp. 280-1. 17 Quoted in HJ. Hanham, Ekctions and Party Management: Politics in the Time of Disraeli and Gladstone ( 1978) p. 202. 18 Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Propaganda (1939) pp. 131-3. 19 Ibid., p. 171. 20 Ibid. 21 See Max Atkinson, Our Masters' Voices (1988) pp. 13-14. 22 Quoted in Michael Thomas, The Economist Guide to Marketing (1986). 23 Michael J. Baker, 'One More Time- What is Marketing?', in Michael J. -

LOSE-UP Bernard Ingham

LOSE-UP Bernard Ingham I always think of Bernard above his merits, after fumb- Ingham as 'the ruffian on the ling he was first demoted stair'. Partly because it fits then ruthlessly cut down and his heavy manner and a treated below those merits. facial expression modulat- Moore went in 18 months ing from scowl to snarl by from golden hero to dogfood. way of a derisive grin. But Yet the prime minister's also because WE Henley, Renaissance treachery, her when he created the phrase, capriciousness and essential was describing Death. falseness have never extended Bernard Ingham has been to her private office. Ber- Death to a number of Conser- nard Ingham could quote vative politicians. Patrick Lear to Cordelia: 'We'll wear Jenkin, his position weakened out...packs and sets of great by the Lords' rejection of ones that ebb and flow by the Mrs Thatcher's decision to moon'. Why such trust amid abolish the GLC, learned that capriciousness, such mons- he was at one with the angels trous durability? What are when Ingham told the press the affinities which hold this that it was all up with Jenkin. pair in a magnetic field? After John Biffen had com- Bernard Ingham is a pro- mitted the capital offence of duct of the Left and of the dissent it was Ingham, telling north of England (Hebden the lobby that he had become Bridge in Yorkshire's West 'semi-detached from the gov- Riding). As is well known, he ernment', who held out a has been a Labour council- signed death warrant. -

The Yorkshire Town That's Gone from Dirty Old Buildings to New Age Nirvana | the Spectator

The Yorkshire town thatʼs gone from dirty old buildings to New Age nirvana | The Spectator 27/09/2018, 20�59 The Yorkshire town that’s gone from dirty old buildings to New Age nirvana William Cook From dirty old town... to New Age nirvana Bernard Ingham once told a story about a reporter from the Financial Times who went to cover an election in Ingham’s hometown of Hebden Bridge. The reporter went into a café and ordered a cappuccino. ‘Nay lad,’ said the waitress. ‘You’ll have to go to Leeds for that.’ Ingham told that story to illustrate the no-nonsense attitudes of the rugged town he grew up in — attitudes that shaped the man who became Margaret Thatcher’s muscular press secretary. So it’s wonderfully ironic that Hebden Bridge is now full of fair trade craft shops and vegan cafés. Nowadays you’ll have no trouble ordering a cappuccino — so long as you like it made from ethically sourced coffee beans. Like that Financial Times(&%(*( 7()*#*% $( *%-( *$-)&&( story. My story was about Ted Hughes, who grew up a few miles away, in https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/09/the-yorkshire-town-thats-gone-from-dirty-old-buildings-to-new-age-nirvana/ Page 1 of 5 The Yorkshire town thatʼs gone from dirty old buildings to New Age nirvana | The Spectator 27/09/2018, 20�59 Mytholmroyd. Later, Ted lived in Heptonstall, a windswept village up on the moors %, $( - * )7()*- /", "**(/", ! ""()") was buried in the graveyard there. Mytholmroyd hasn’t changed much and nor has Heptonstall. So how come Hebden ( $*($)%(#(%# (*/%"*%-$*%-$ (,$$)-( ) hippies and lesbians. -

The Religious Mind of Mrs Thatcher

The Religious Mind of Mrs Thatcher Antonio E. Weiss June 2011 The religious mind of Mrs Thatcher 2 ------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT Addressing a significant historical and biographical gap in accounts of the life of Margaret Thatcher, this paper focuses on the formation of Mrs Thatcher’s religious beliefs, their application during her premiership, and the reception of these beliefs. Using the previously unseen sermon notes of her father, Alfred Roberts, as well as the text of three religious sermons Thatcher delivered during her political career and numerous interviews she gave speaking on her faith, this paper suggests that the popular view of Roberts’ religious beliefs have been wide of the mark, and that Thatcher was a deeply religious politician who took many of her moral and religious beliefs from her upbringing. In the conclusion, further areas for research linking Thatcher’s faith and its political implications are suggested. Throughout this paper, hyperlinks are made to the Thatcher Foundation website (www.margaretthatcher.org) where the sermons, speeches, and interviews that Margaret Thatcher gave on her religious beliefs can be found. The religious mind of Mrs Thatcher 3 ------------------------------------------- INTRODUCTION ‘The fundamental reason of being put on earth is so to improve your character that you are fit for the next world.’1 Margaret Thatcher on Today BBC Radio 4 6 June 1987 Every British Prime Minister since the sixties has claimed belief in God. This paper will focus on just one – Margaret Thatcher. In essence, five substantive points are argued here which should markedly alter perceptions of Thatcher in both a biographical and a political sense. -

CORRECTED TRANSCRIPT of ORAL EVIDENCE to Be Published As HC 707-Vi

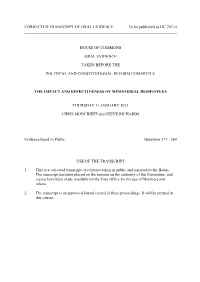

CORRECTED TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL EVIDENCE To be published as HC 707-vi HOUSE OF COMMONS ORAL EVIDENCE TAKEN BEFORE THE POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM COMMITTEE THE IMPACT AND EFFECTIVENESS OF MINISTERIAL RESHUFFLES THURSDAY 31 JANUARY 2013 CHRIS MONCRIEFF and STEVE RICHARDS Evidence heard in Public Questions 317 - 360 USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken in public and reported to the House. The transcript has been placed on the internet on the authority of the Committee, and copies have been made available by the Vote Office for the use of Members and others. 2. The transcript is an approved formal record of these proceedings. It will be printed in due course. 1 Oral Evidence Taken before the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee on Thursday 31 January 2013 Members present: Mr Graham Allen (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope Sheila Gilmore Fabian Hamilton Mrs Eleanor Laing Mr Andrew Turner Stephen Williams ________________ Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Chris Moncrieff, Press Association, and Steve Richards, The Independent, gave evidence. Q317 Chair: Chris, good morning; and Steve, welcome. As you know, we are conducting an inquiry into reshuffles, and we have been taking evidence from many people. We hope to conclude this in the not-too-distant future. We have one further witness to come, Gus O’Donnell, and then we will start writing up a report. Some very interesting comment has been made about the whole process, and, of course, halfway through our inquiry, the Prime Minister—just to help us along—had a reshuffle, so that we could have a look at one first hand. -

Newspaper of the Campaign for Freedom of Information No.17

New spaper af the Cam pa ign fo r Freedom of Information Number Number 17 May 1989 70% of MPs suppqJport Call1paign'! call for reform (j111 of the Lobby The Campaign for Freedom of Infor kite, and if the react ion to the idea is BBC and lTV that minist. mation has extended its activit ies to bad, they can drop it. Or it is unat not be allowed to dictate th cover reform of the lobby system , the tributable to counter another unat of appearances. Where the. exposure of media manipulation, and tributable briefing given by the Prime to appear in serious discus: research into and publicity of abuse of ~ign Minister or other ministers. Often they major policy issues, thei Whitehall information resources . want to spread mis-information, either should be left vacant. The gn f by untruths, or by misrepresentations In a major speech at the House of ' . should be told that, of cou Commons, Des Wilson, co-chairman of facts, and want to cover their back. Minister or his representativ of the Campaign for Freedom of In "It is surely a relatively safe max had the opportunity to ap .~ "'~ im that whenever someone says "don't formation, said that the absence of fl'. 4.A radical overhau l of the freedom of, information legislation ;,.~ I n n f o quote me on this ..." there's at least Whitehall information offie and the enactment of even tighter a chance they are either breaking a information expend iture. secrecy legislation mean t that the confidence, saying something that they In his speech Des Wilson ~ publ ic were increasingly dependent on are unsure will stand up, lying, or in that the Campaign was not ant the media, yet in many ways the media some other way acting dishono urably. -

2020/26/37

" . 2 t i ·11 a l r l1 i ,, 1 2020/26/37 1;c / 3 <to; n imhlr n Ulmhlr ag Rolnn Elle Data Cuireadh chun Culreadh chun Data Cuireadh chun START of file 1 - SECRET ANGLO-IRISH SECTION WEEKLY BRIEF WEEK ENDING 30TH NOVEMBER 1990 1 C O N T E N T S 1 . Reports from Anglo-Irish Secretariat Address by the Rev. Ian Paisley to DUP Annual Conference 'Accompaniment of the British Army 2. Contact and Information Work Conversation with Fr. McCluskey P.P., Roslea, Co. Fermanagh 3. Reports from Embassy London The New Prime Minister - an Initial Assessment John Major - media reactions Discussion with Derek Hill (NIO) on Secretary of State's views on talks Birmingham Six DPP to seek to uphold convictions Gareth Peirce on DPP's decision to contest case Northern Ireland Backbench Committee - Stanbrook succeeds 4. Reports from Embassy Washington Remarks by Sherard Cowper-Coles, First Secretary, British Embassy 1 0 .. D.U.l. Confer nee l'ir ~ Als n has i \ n n1 a ~ o ~ Iaic.l:1 's sp eh wh'ch I · t acl1~ U 1ill S h t as on h sp, ech · s und on pag f u. und ~sta1d tl1at thi~ ion w s und rl'n l1 DU l1ems 1 \·es o h atten ion of M ~ rook. ou w no e aisl 1 a .. ues: - Tha the B~itish Government has agre d th t th Un'on's s will be ar of the UK negotiating team nd h i Unionis s a"'e "plenipotentiaries" with the a -·t-sh Gov ~nment then they will know exactly wh t is t ~1n pl c · and will have the advantage of being ble to gu h ir case personally and forthrightly without ny h h , might be betrayed (by the British). -

100 Years of Government Communication

AZ McKenna 100 Years of Government Communication AZ McKenna John Buchan, the frst Director of Information appointed in 1917 Front cover: A press conference at the Ministry of Information, 1944 For my parents and grandparents © Crown copyright 2018 Tis publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identifed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. 100 YEARS OF GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must frstly record my thanks to Alex Aiken, Executive Director of Government Communication, who commissioned me to write this book. His interest in it throughout its development continues to fatter me. Likewise I am indebted to the Government Communication Service who have overseen the book’s production, especially Rebecca Trelfall and Amelie Gericke. Te latter has been a model of eficiency and patience when it has come to arranging meetings, ordering materials and reading every draft and redraft of the text over the last few months. I am also grateful for the efforts of Gabriel Milland – lately of the GCS – that laid much of the groundwork for the volume. However, I would never even have set foot in the Cabinet Ofice had Tom Kelsey of the Historians in Residence programme at King’s College London not put my name forward. I am also hugely grateful to numerous other people at King’s and within the wider University of London. In particular the contemporary historians of the Department of Political Economy – among them my doctoral supervisors Michael Kandiah and Keith Hamilton – and those associated with the International History Seminar of the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) – Michael Dockrill, Matthew Glencross, Kate Utting as well as many others – have been a constant source of advice and encouragement. -

PSA Awards 2010

AWARD WINNERS TUESDAY 30 NOVEMBER 2010 One Great George Street, London SW1P 3AA THE AWARDS Politician of Year 2010..................................................................3 Lifetime Achievement in Politics ..............................................5 Parliamentarian .............................................................................7 Setting the Political Agenda .......................................................9 Political Journalist.......................................................................11 Broadcast Journalist ..................................................................12 Special ‘Engaging the Public’ Award .......................................13 Best Political Satire.....................................................................14 Lifetime Achievement in Political Studies............................16 Politics/Political Studies Communicator .............................19 Sir Isaiah Berlin Prize for Lifetime Contribution to Political Studies ..........................................................................20 Best book in British political studies 1950-2010 ...............21 W. J. M. MacKenzie Prize 2010 .................................................22 ANNUAL AWARD POLITICIAN OF YEAR 2010 This is an award for domestic politicians who have made a significant impact in 2010. Any person elected for political office in the UK can be considered. The Judges Say described him as “one of the ablest” Despite the inconclusive outcome of the students he has taught. 2010 general -

Science Policy Under Thatcher

Science Policy under Thatcher Science Policy under Thatcher Jon Agar First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Jon Agar, 2019 Jon Agar has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Agar, J. 2019. Science Policy under Thatcher. London, UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353411 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to re-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons license, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-78735-343-5 (Hbk) ISBN: 978-1-78735-342-8 (Pbk) ISBN: 978-1-78735-341-1 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-78735-344-2 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-78735-345-9 (mobi) ISBN: 978-1-78735-346-6 (html) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353411 For Kathryn, Hal and Max, and my parents Ann and Nigel Agar. -

House of Lords

HOUSE OF LORDS Thursday 12th June 2008 Politics and the media - better or worse in the last 50 years By the Rt Hon Baroness Jay of Paddington I am honoured to conclude this distinguished series of lectures organised by the Lord Speaker and Queen Mary’s College, University of London where my old friend Professor Peter Hennessey – has, in my view, done more to enhance our understanding of recent British history than anyone else writing today. It is a particular honour to be introduced by the Lord Speaker, and I would like to pay tribute to Helene Hayman’s energy and imagination in arranging this programme and taking many other initiatives to increase general awareness of the contemporary work of the House of Lords. It is hard to remember that the position of the Lord Speaker is still less than two years old! In this short time Baroness Hayman has done so much to establish an important role in public life, and this occasion which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the first women life peers is a good opportunity to congratulate her. Previous speakers in the series have been experts in their field but I think it would be hard for anyone to claim unrivalled specialist knowledge of my topic – “politics and the media over the last 50 years”. But, no doubt, everyone in the room has strong opinions on the subject, everyone always has! My own opinions have been formed by my personal history. 2008 is the golden jubilee of the Life Peerages Act, it is also the golden jubilee of my arrival at Oxford University where I began a career in student journalism - eventually achieving the glittering prize of deputy to David Dimbleby as editor of the undergraduate magazine “isis”. -

The Impact of European Monetary Integration on the Labour and Conservative Parties in Britain, 1983–2003

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-1-2011 The Impact of European Monetary Integration on the Labour and Conservative Parties in Britain, 1983–2003 Denise Froning University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Economics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Froning, Denise, "The Impact of European Monetary Integration on the Labour and Conservative Parties in Britain, 1983–2003" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 214. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/214 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE IMPACT OF EUROPEAN MONETARY INTEGRATION ON THE LABOUR AND CONSERVATIVE PARTIES IN BRITAIN, 1983-2003 __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Denise Froning August 2011 Advisor: Frank Laird ©Copyright by Denise Froning 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Denise Froning Title: THE IMPACT OF EUROPEAN MONETARY INTEGRATION ON THE LABOUR AND CONSERVATIVE PARTIES IN BRITAIN, 1983-2003 Advisor: Frank Laird Degree Date: August 2011 ABSTRACT