Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haessly, Katie (2010) British Conservative Women Mps

British Conservative Women MPs and ‘Women’s Issues’ 1950-1979 Katie Haessly, BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 1 Abstract In the period 1950-1979, there were significant changes in legislation relating to women’s issues, specifically employment, marital and guardianship and abortion rights. This thesis explores the impact of Conservative female MPs on these changes as well as the changing roles of women within the party. In addition there is a discussion of the relationships between Conservative women and their colleagues which provides insights into the changes in gender roles which were occurring at this time. Following the introduction the next four chapters focus on the women themselves and the changes in the above mentioned women’s issues during the mid-twentieth century and the impact Conservative women MPs had on them. The changing Conservative attitudes are considered in the context of the wider changes in women’s roles in society in the period. Chapter six explores the relationship between women and men of the Conservative Parliamentary Party, as well as men’s impact on the selected women’s issues. These relationships were crucial to enhancing women’s roles within the party, as it is widely recognised that women would not have been able to attain high positions or affect the issues as they did without help from male colleagues. Finally, the female Labour MPs in the alteration of women’s issues is discussed in Chapter seven. Labour women’s relationships both with their party and with Conservative women are also examined. -

In This Issue

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 1 October 2003 74035 $4.00 I In This Issue I In Zelda Fitzgerald, biographer Sally Cline argues that it is as a visual artist in her own right that Zelda should be remembered—and cer- tainly not as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s crazy wife. Cover story D I What you’ve suspected all along is true, says essayist Laura Zimmerman—there really aren’t any feminist news commentators. p. 5 I “Was it really all ‘Resilience and Courage’?” asks reviewer Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild of Nehama Tec’s revealing new study of the role of gender during the Nazi Holocaust. But generalization is impossible. As survivor Dina Abramowicz told Tec, “It’s good that God did not test me. I don’t know what I would have done.” p. 9 I No One Will See Me Cry, Zelda (Sayre) Fitzgerald aged around 18 in dance costume in her mother's garden in Mont- Cristina Rivera-Garza’s haunting gomery. From Zelda Fitzgerald. novel set during the Mexican Revolution, focuses not on troop movements but on love, art, and madness, says reviewer Martha Gies. p. 11 Zelda comes into her own by Nancy Gray I Johnnetta B. Cole and Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s Gender Talk is the Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline. book of the year about gender and New York: Arcade, 2002, 492 pp., $27.95 hardcover. race in the African American com- I munity, says reviewer Michele Faith ne of the most enduring, and writers of her day, the flapper who jumped Wallace. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

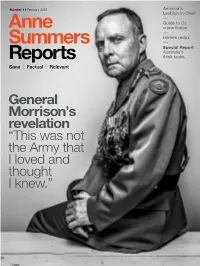

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Popular Culture and Margaret Thatcher, The

ZÁPADOČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V PLZNI FAKULTA FILOZOFICKÁ BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Popular Culture and Margaret Thatcher, the Media Image of the “Iron Lady“ Kateřina Tichá Plzeň 2018 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – francouzština Bakalářská práce Popular Culture and Margaret Thatcher, the Media Image of the “Iron Lady“ Kateřina Tichá Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Tomáš Hostýnek Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2018 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2018 ……………………… Touto cestou bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Tomášovi Hostýnkovi, za cenné rady a připomínky v průběhu psaní mé bakalářské práce, které pro mě byly velmi přínosné. Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 2 EARLY LIFE 1925 – 1947 .......................................................... 3 2.1 Childhood ..................................................................................... 3 2.2 Education ...................................................................................... 3 2.3 Relation towards her parents ..................................................... 4 3 EARLY FORAY INTO POLITICS 1948 – 1959 ........................... 5 4 POLITICAL LIFE 1959 – 1979 ................................................... 7 4.1 Opposition ................................................................................... -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.Thc sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagc(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing pagc(s) or section, they arc spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed cither blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame* If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Its Stories, People, and Legacy

THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Its Stories, People, and Legacy Edited by RALPH IZARD THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Its Stories, People, and Legacy Edited by Ralph Izard Ohio University Press Athens Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 ohioswallow.com © 2018 by Ohio University Press All rights reserved To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax). Printed in the United States of America Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ™ 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1 Frontispiece: Schoonover Center for Communication, home of the school, 2013–present. (Photo courtesy of Ohio University) Photographs, pages xiv, xx, 402, and 428: Scripps Hall, home of the school, 1986–2013. (Photo courtesy of Ohio University) Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8214-2315-8 Electronic ISBN: 978-0-8214-4630-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018945765 The E.W. Scripps School of Journalism is indebted to G. Kenner Bush for funding this project through the Gordon K. Bush Memorial Fund. The fund honors a longtime pub- lisher of The Athens Messenger who was a special friend to the school. -

MS 288 Morris Papers

MS 288 Morris Papers Title: Morris Papers Scope: Papers and correspondence of Brian Robert Morris, 4th Dec 1930-30 April 2001: academic, broadcaster, chairman/member of public and private Arts and Heritage related organizations and Life Peer, with some papers relating to his father Dates: 1912-2002 Level: Fonds Extent: 45 boxes Name of creator: Brian Robert Morris, Lord Morris of Castle Morris Administrative / biographical history: The collection comprises the surviving personal and working papers, manuscripts and associated correspondence relating to the life and work of Brian Robert Morris, university teacher and professor of English Literature, University Principal, writer, broadcaster and public figure through his membership/chairmanship of many public and private cultural bodies and his appointment to the House of Lords. He was born in 1930 in Cardiff, his father being a Pilot in the Bristol Channel, who represented the Pilots on the Cardiff Pilotage Authority, was a senior Mason and was active in the Baptist Church. Brian attended Marlborough Road School, where one of his masters was George Thomas, later Speaker of the House of Commons, and then Cardiff High School. He was brought up monolingual in English and though he learnt Welsh in later life, especially while at Lampeter, no writings in Welsh survive in the archive. He served his National Service with the Welch Regiment, based in Brecon and it was in Brecon Cathedral that his conversion to Anglicanism from his Baptist upbringing, begun as he accompanied his future wife to Church in Wales services, was completed. Anglicanism remained a constant part of his life: he became a Lay Reader when in Reading, was a passionate advocate of the Book of Common Prayer and a fierce critic of Series Three and the New English Bible, as epitomised in the book he edited in 1990, Ritual Murder . -

Secret Secret

SECRET CUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HER BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT )33rd COPY NO SO usions . CABINET CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at 10 Downing Street on THURSDAY 18 SEPTEMBER 1980 at 10. 30 am PRESENT The Rt Hon Margaret Thatcher MP Prime Minister t Hon William Whitelaw MP The Rt Hon Lord Hailsham tary of State for the Home Department Lord Chancellor .tHon Sir Geoffrey Howe QC MP The Rt Hon Sir Keith Joseph MP ellor of the Exchequer Secretary of State for Industry t Hon Francis Pym MP The Rt Hon Lord Soames tary of State for Defence Lord President of the Council tHon James Prior MP The Rt Hon Sir Ian Gilmour MP tary of State for Employment Lord Privy Seal tHon Michael Heseltine MP The Rt Hon Nicholas Edwards MP tary of State for the Environment Secretary of State for Wales t Hon Humphrey Atkins MP The Rt Hon Patrick Jenkin MP tary of State for Northern Ireland Secretary of State for Social Services tHon Norman St John-Stevas MP The Rt Hon John Nott MP ellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Secretary of State for Trade t Hon Mark Carlisle QC MP The Rt Hon John Biffen MP tary of State for Education and Science Chief Secretary, Treasury The Rt Hon Angus Maude MP Paymaster General -i- SECRET SECRET THE FOLLOWING WERE ALSO PRESENT IHon Lord Mackay of Clashfern QC Sir Ian Percival QC MP ivocate (Item 4) Solicitor General (Item 4) Hon Norman Fowler MP The Rt Hon Michael Jopling MP |r of Transport Parliamentary Secretary, Treasury SECRETARIAT Sir Robert Armstrong Mr M D M Franklin (Items 1, 2 and 4) Mr P Le Chemir.ant (Item 3) Mr R L Wade-Gery (Items 1 and 2) Mr D M Elliott (Item 4) Mr D J L Moore (Item 3) C ONTENTS Subject Page FOREIGN AFFAIRS Poland 1 Turkey 1 Middle East 2 Iran 2 Afghanistan 2 Zimbabwe 2 Canada 2 COMMUNITY AFFAIRS Foreign Affairs Council 3 ii SECRET SECRET Subject Page ECONOMIC AND HOME AFFAIRS Threatened National Dock Strike 5 Welsh Television 5 The Economic Situation 6 Local Authority Expenditure 7 COMMISSION DIRECTIVE UNDER ARTICLE 90 OF THE TREATY OF ROME 8 iii SECRET CONFIDENTIA 1. -

Download (2260Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4527 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Liza Filby University of Warwick University ID Number: 0558769 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. ……………………………………………… Date………… 2 Abstract The core theme of this thesis explores the evolving position of religion in the British public realm in the 1980s. Recent scholarship on modern religious history has sought to relocate Britain‟s „secularization moment‟ from the industrialization of the nineteenth century to the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. My thesis seeks to add to this debate by examining the way in which the established Church and Christian doctrine continued to play a central role in the politics of the 1980s. More specifically it analyses the conflict between the Conservative party and the once labelled „Tory party at Prayer‟, the Church of England. Both Church and state during this period were at loggerheads, projecting contrasting visions of the Christian underpinnings of the nation‟s political values. The first part of this thesis addresses the established Church.