Its Stories, People, and Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game 1 UCLA at Texas A&M - 12:30 P.M

UCLA FOOTBALL 2016 RELEASE - UCLA at Texas A&M 2016 BRUIN FOOTBALL FOOTBALL CONTACTS: STEVE ROURKE/SKIP POWERS :: 310-206-6831 E-MAIL - [email protected], [email protected] SHIPPING ADDRESS - UCLA SPORTS INFO :: JD MORGAN CENTER :: 325 WESTWOOD PLAZA :: LOS ANGELES, CA 90095 Coming Up UCLA OPENS 2016 SEASON WITH SEC MATCH UP AT TEXAS A&M Sat., Sept. 3 - Game 1 UCLA at Texas A&M - 12:30 p.m. PT CBS No. 16/24 UCLA at A&M on Sept. 3 at 12:30 p.m. PT - CBS Sports Sat., Sept. 10 - Game 2 UNLV at UCLA - 5:00 p.m. PT P12N Home Opener: Sept. 10 vs. UNLV in Rose Bowl 2016 SEASON KICKS OFF AT TEXAS A&M ON SEPT. 3 — No. 16 (AP) /24 (Coaches) UCLA opens the 2016 football season on Saturday, Sept. 3 at 12:30 p.m. PT at College Station, Texas versus Texas A&M. The game will be televised by CBS. Call- ing the game will be Verne Lundquist, Gary Danielson and Allie LaForce. The Bruin IMG Radio Network (Josh Lewin, Matt Stevens, Wayne Cook) will radio broadcast the contest on 570am LA Sports. The contest will also be aired over Sirius/XM (Ch. 81), uclabruins.com and tunein.com and the TuneIn App. UCLA will open a campaign on the road for the fi fth time in the last seven seasons. The Bruins defeated Virginia in last season’s opener in the Rose Bowl (34-16). UCLA kicked off the 2014 campaign with a 28-20 win in Charlottesville. -

30Th ANNUAL MAYBERRY DAYS®

30th ANNUAL MAYBERRY DAYS® Celebrating the 59th Anniversary of TAGS Once Upon 30 Times, ® WELCOME to MAYBERRY DAYS® There Is Mayberry Days ! Guests from the cast and production team of TAGS include By Jim Clark Betty Lynn, Calvin Peeler, Rodney Dillard, Maggie Peterson- It’s the 30th Annual Mayberry Days®. Mancuso, LeRoy McNees, Margaret Kerry, Clint Howard, Shazam! Ronnie Schell, Keith Thibodeaux, Joy Ellison, Dennis Rush, For some of us attending this year’s Bruce Bilson, Gary Nelson, and Karen Knotts. Additional festival, this milestone event marks special guests include Bettina Linke, Dick Atkins, Dreama roughly half a lifetime. For younger Denver, Gregory Schell, Stark Howell, and Cort Howell. attendees, the 30th annual of anything probably seems impossibly ancient—as long ago as life without the internet’s SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS World Wide Web, which, incidentally, MOUNT AIRY CHRYSLER DODGE JEEP RAM FIAT wasn’t made available for public use 508 N. Andy Griffith Parkway until the year after the first Mayberry Days. Even for older attendees, 30 Mayberry Days festivals represent more than just a waystation along life’s journey. The festival has been a deep commitment by the Surry Arts Council, the City of Mount Many of the trucks and cars in the Mayberry Days® Parade are Airy, the cast and crew of The Andy Griffith Show (and their families), and other performers, as provided by our sponsor. Check out their vehicles at the golf well as by fans themselves. tournament, the Blackmon Amphitheatre, and at the Andy Griffith We all gather the last week of September to toast a TV show that we love and the people Playhouse and Museum. -

The Day Everything Stopped

20131118-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 11/15/2013 2:06 PM Page 1 $2.00/NOVEMBER 18 - 24, 2013 THE JOHN F. KENNEDY ASSASSINATON: 50 YEARS LATER The day everything stopped Cleveland icons recall the ‘intangible sadness’ they felt when they first heard the grim news By JAY MILLER “I was on the air, as a matter of fact, and all [email protected] of the sudden the teletype went crazy,” re- called Bob Conrad, who was a co-owner of ot long after 1:20 p.m. on Nov. 22, WCLV-FM, then and now Cleveland’s classical 1963, workers at the May Co.’s music radio station. He went to the Associated downtown Cleveland store moved Press wire machine and ripped the story from a television set wired to an out- its roll. He rushed back to the booth and told Ndoor loudspeaker into a display window fac- listeners that the president had been shot. ing Public Square. Passersby soon were clus- “We continued what we were (playing) tered around the black-and-white glow. until we got confirmation Kennedy was Minutes earlier, President John F. dead,” Mr. Conrad said. “Then we put the Kennedy had been fatally wounded as his Mozart’s Requiem (the haunting ‘Requiem motorcade was carrying him to a speaking Mass in D Minor’) on the air.” engagement in downtown Dallas. He then canceled all commercials. For as long as the workday continued, ra- “We did that because I remembered lis- dios and televisions were turned on in of- tening to the radio when (President Franklin fices, schools and factories in Northeast D.) Roosevelt died,” he said. -

Dissertation on Carter

© 2012 Casey Robards All rights reserved. JOHN DANIELS CARTER: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND MUSICAL PROFILE WITH ORIGINAL PIANO TRANSCRIPTION OF REQUIEM SEDITIOSAM: IN MEMORIAM MEDGAR EVERS BY CASEY ROBARDS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Vocal Coaching and Accompanying in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Reid Alexander, Chair and Director of Research Professor Dennis Helmrich Professor Emeritus Herbert Kellman Associate Professor Stephen Taylor Abstract African-American pianist and composer John Daniels Carter (1932-1981) is widely recognized for his Cantata for voice and piano (also arranged for voice and orchestra), Carter’s only published work. However, relatively little information has been published about Carter’s life, his compositional output, or career as a pianist. His date of birth and death are often listed incorrectly; the last decade of his life remains undocumented. There is also confusion in the database of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) regarding the attributions of his unpublished compositions, compounded by the existence of another composer who has arranged several spirituals, and a jazz clarinetist, both named John Carter. In-depth field research, over a three-year period, was conducted to discover more information about Carter. Through newspaper articles, archival material from the Kennedy Center/Rockefeller Archives, and conversations or correspondence with those who knew Carter personally, this dissertation presents biographical information about Carter’s musical education, performance activity as a pianist, and career as a composer-in-residence with the Washington National Symphony. -

2001 Report of Gifts (133 Pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society - Annual South Caroliniana Library Report of Gifts 5-19-2001 2001 Report of Gifts (133 pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Publication Info 2001. University South Caroliniana Society. (2001). "2001 Report of Gifts." Columbia, SC: The ocS iety. This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society - Annual Report of Gifts yb an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The The South Carolina South Caroliniana College Library Library 1840 1940 THE UNIVERSITY SOUTH CAROLINIANA SOCIETY SIXTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Saturday, May 19, 2001 Dr. Allen H. Stokes, Jr., Secretary-Treasurer, Presiding Reception and Exhibit . .. 11 :00 a.m. South Caroliniana Library Luncheon 1:00 p.m. Clarion Townhouse Hotel Business Meeting Welcome Reports of the Executive Council and Secretary-Treasurer Address . Genevieve Chandler Peterkin 2001 Report of Gifts to the Library by Members of the Society Announced at the 65th Annual Meeting of the University South Caroliniana Society (the Friends of the Library) Annual Program 19 May 2001 South Carolina's Pivotal Decision for Disunion: Popular Mandate or Manipulated Verdict? – 2000 Keynote Address by William W. Freehling Gifts of Manuscript South Caroliniana Gifts to Modern Political Collections Gifts of Pictorial South Caroliniana Gifts of Printed South Caroliniana South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC) A special collection documenting all periods of South Carolina history. -

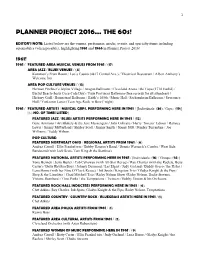

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 60S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 60s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting 1961 and 1966 in Planner Project 2016! 1961! 1961 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1961 / (17) AREA JAZZ / BLUES VENUES / (4) Kornman’s Front Room / Leo’s Casino (4817 Central Ave.) / Theatrical Restaurant / Albert Anthony’s Welcome Inn AREA POP CULTURE VENUES / (13) Herman Pirchner’s Alpine Village / Aragon Ballroom / Cleveland Arena / the Copa (1710 Euclid) / Euclid Beach (hosts Coca-Cola Day) / Four Provinces Ballroom (free records for all attendees) / Hickory Grill / Homestead Ballroom / Keith’s 105th / Music Hall / Sachsenheim Ballroom / Severance Hall / Yorktown Lanes (Teen Age Rock ‘n Bowl’ night) 1961 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GRPS. PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (36) / Grps.: (19)] [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED JAZZ / BLUES ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / (12) Gene Ammons / Art Blakely & the Jazz Messengers / John Coltrane / Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison / Ramsey Lewis / Jimmy McPartland / Shirley Scott / Jimmy Smith / Sonny Stitt / Stanley Turrentine / Joe Williams / Teddy Wilson POP CULTURE: FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1961 / (6) Andrea Carroll / Ellie Frankel trio / Bobby Hanson’s Band / Dennis Warnock’s Combo / West Side Bandstand (with Jack Scott, Tom King & the Starfires) FEATURED NATIONAL ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (16) / Groups: (14)] Tony Bennett / Jerry Butler / Cab Calloway (with All-Star -

The State Records of South Carolina Journals of the HOUSE OF

The State Records of South Carolina Journals of the HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, 1789-1790 MICHAEL E. STEVENS Editor CHRISTINE M. ALLEN Assistant Editor Published for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History by the University of South Carolina Press Columbia, SC 8557 Copyright ©1984 by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History First Edition Published in Columbia, SC by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN 0-87249-944-8 20 JANUARY 1790 (page) 363 thereto, Our Committee are Mr. Hugh Rutledge, Major Pinckney & Mr. Deas. By order of the House, Jacob Read, Speaker Ordered That the Message be sent to the Senate and that Mr. Hugh Rutledge and Mr. Deas do carry the same. The House proceeded to the Second reading of a Bill to Incoporate the Baptist Church on Hornes Creek in Edgefield County, State of South Carolina, when a Motion was made and Seconded that the Bill be changed into An Ordinance, which was agreed to -- the Ordinance then read through and agreed to Ordered That the Ordinance be sent to the Senate and that Mr. Simpkins and Colonel Anderson do carry the same. And then the House Adjourned 'til to morrow Morning 10 o'Clock. WEDNESDAY JANUARY 20TH 1790 Read The Journals of Yesterday’s proceedings. Mr. Speaker Administered the Oath to Support the Constitution of the United States to Mr. Robert Patton, a Member of this House. A Motion was made and Seconded, that a Message be sent to the Senate informing them that this House propose to Ratify such Acts and Ordinances as are Engrossed, and the Great Seal of the State affixed thereto at 1 o'Clock this day, and then to Adjourn to Saturday the Twenty Seventh day of November 1790, which being agreed to, the following Message was accordingly prepared Vizt. -

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021)

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021) I’ve been amassing corrections and additions since the August, 2012 publication of Pepper Adams’ Joy Road. Its 2013 paperback edition gave me a chance to overhaul the Index. For reasons I explain below, it’s vastly superior to the index in the hardcover version. But those are static changes, fixed in the manuscript. Discographers know that their databases are instantly obsolete upon publication. New commercial recordings continue to get released or reissued. Audience recordings are continually discovered. Errors are unmasked, and missing information slowly but surely gets supplanted by new data. That’s why discographies in book form are now a rarity. With the steady stream of updates that are needed to keep a discography current, the internet is the ideal medium. When Joy Road goes out of print, in fact, my entire book with updates will be posted right here. At that time, many of these changes will be combined with their corresponding entries. Until then, to give you the fullest sense of each session, please consult the original entry as well as information here. Please send any additions, corrections or comments to http://gc-pepperadamsblog.blogspot.com/, despite the content of the current blog post. Addition: OLIVER SHEARER 470900 September 1947, unissued demo recording, United Sound Studios, Detroit: Willie Wells tp; Pepper Adams cl; Tommy Flanagan p; Oliver Shearer vib, voc*; Charles Burrell b; Patt Popp voc.^ a Shearer Madness (Ow!) b Medley: Stairway to the Stars A Hundred Years from Today*^ Correction: 490900A Fall 1949 The recording was made in late 1949 because it was reviewed in the December 17, 1949 issue of Billboard. -

Sports Emmy Awards

Sports Emmy Awards OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SPECIAL 2018 College Football Playoff National Championship ESPN Alabama Crimson Tide vs. Georgia Bulldogs The 113th World Series FOX Houston Astros vs Los Angeles Dodgers The 118th Army-Navy Game CBS The 146th Open NBC/Golf Channel Royal Birkdale The Masters CBS OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SERIES NASCAR on FOX FOX/ FS1 NBA on TNT TNT NFL on FOX FOX Deadline Sunday Night Football NBC Thursday Night Football NBC 8 OUTSTANDING PLAYOFF COVERAGE 2017 NBA Playoffs on TNT TNT 2017 NCAA Men's Basketball Tournament tbs/CBS/TNT/truTV 2018 Rose Bowl (College Football Championship Semi-Final) ESPN Oklahoma vs. Georgia AFC Championship CBS Jacksonville Jaguars vs. New England Patriots NFC Divisional Playoff FOX New Orleans Saints vs. Minnesota Vikings OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS EVENT COVERAGE 2017 World Series Film FS1/MLB Network Houston Astros vs. Los Angeles Dodgers All Access Epilogue: Showtime Mayweather vs. McGregor [Showtime Sports] Ironman World Championship NBC Deadline[Texas Crew Productions] Sound FX: NFL Network Super Bowl 51 [NFL Films] UFC Fight Flashback FS1 Cruz vs. Garbrandt [UFC] 9 OUTSTANDING SHORT SPORTS DOCUMENTARY Resurface Netflix SC Featured ESPNews A Mountain to Climb SC Featured ESPN Arthur SC Featured ESPNews Restart The Reason I Play Big Ten Network OUTSTANDING LONG SPORTS DOCUMENTARY 30 for 30 ESPN Celtics/Lakers: Best of Enemies [ESPN Films/Hock Films] 89 Blocks FOX/FS1 Counterpunch Netflix Disgraced Showtime Deadline[Bat Bridge Entertainment] VICE World of Sports Viceland Rivals: -

MS 288 Morris Papers

MS 288 Morris Papers Title: Morris Papers Scope: Papers and correspondence of Brian Robert Morris, 4th Dec 1930-30 April 2001: academic, broadcaster, chairman/member of public and private Arts and Heritage related organizations and Life Peer, with some papers relating to his father Dates: 1912-2002 Level: Fonds Extent: 45 boxes Name of creator: Brian Robert Morris, Lord Morris of Castle Morris Administrative / biographical history: The collection comprises the surviving personal and working papers, manuscripts and associated correspondence relating to the life and work of Brian Robert Morris, university teacher and professor of English Literature, University Principal, writer, broadcaster and public figure through his membership/chairmanship of many public and private cultural bodies and his appointment to the House of Lords. He was born in 1930 in Cardiff, his father being a Pilot in the Bristol Channel, who represented the Pilots on the Cardiff Pilotage Authority, was a senior Mason and was active in the Baptist Church. Brian attended Marlborough Road School, where one of his masters was George Thomas, later Speaker of the House of Commons, and then Cardiff High School. He was brought up monolingual in English and though he learnt Welsh in later life, especially while at Lampeter, no writings in Welsh survive in the archive. He served his National Service with the Welch Regiment, based in Brecon and it was in Brecon Cathedral that his conversion to Anglicanism from his Baptist upbringing, begun as he accompanied his future wife to Church in Wales services, was completed. Anglicanism remained a constant part of his life: he became a Lay Reader when in Reading, was a passionate advocate of the Book of Common Prayer and a fierce critic of Series Three and the New English Bible, as epitomised in the book he edited in 1990, Ritual Murder . -

TWICE a CITIZEN Celebrating a Century of Service by the Territorial Army in London

TWICE A CITIZEN Celebrating a century of service by the Territorial Army in London www.TA100.co.uk The Reserve Forces’ and Cadets’ Association for Greater London Twice a Citizen “Every Territorial is twice a citizen, once when he does his ordinary job and the second time when he dons his uniform and plays his part in defence.” This booklet has been produced as a souvenir of the celebrations for the Centenary of the Territorial Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, Army in London. It should be remembered that at the time of the formation of the Rifle Volunteers 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC in 1859, there was no County of London, only the City. Surrey and Kent extended to the south bank of the Thames, Middlesex lay on the north bank and Essex bordered the City on the east. Consequently, units raised in what later became the County of London bore their old county names. Readers will learn that Londoners have much to be proud of in their long history of volunteer service to the nation in its hours of need. From the Boer War in South Africa and two World Wars to the various conflicts in more recent times in The Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan, London Volunteers and Territorials have stood together and fought alongside their Regular comrades. Some have won Britain’s highest award for valour - the Victoria Cross - and countless others have won gallantry awards and many have made the ultimate sacrifice in serving their country. This booklet may be recognised as a tribute to all London Territorials who have served in the past, to those who are currently serving and to those who will no doubt serve in the years to come. -

It's Your Money – Keep More Of

Where Hendricks County Business Comes First May 2018 | Issue 0153 www.hcbusinessleader.com Trends In Tech Am I ready for custom software Chet Cromer Page 22 Biz Law Managing With the Mayberry in the Midwest Festival weeks employees as a away, Brad and Christine Born, owners of small business Mayberry Cafe, no doubt had any idea in 1993 what Eric Oliver owner their passion would ultimately create Page 17 Open or add to your IRA or Health Savings Account It’s Your Money – by April 17 and you may save on your 2017 taxes. Keep More of it! • IRAs or Roth IRAs • Health Savings Accounts Call Us Today! State Bank of Lizton does not provide tax advice. Avon | Brownsburg | Dover | Jamestown | Lebanon | Lizton | Plainfield | Pittsboro | Zionsville www.StateBankofLizton.com | 866-348-4674 #46913 SBL KeepYourMoneyLady_HCBL9.7x1.25.indd 1 2/12/18 11:52 AM 2 May 2018 • hcbusinessleader.com OPINION Hendricks County Business Leader Our View Quote of the Month Cartoon “Making money is art and Trade working is art and good business is the best art” wars The trade war is not a “real war,” and ~Andy Warhol certainly not new. China has been firing metaphorical bullets for decades and now President Trump is firing back. What apparently started as a move to protect U.S. intellectual property is now a standoff of historical proportions, and domestic manufacturers, farmers and most recently, tech companies are being Humor thrown into the mix. In a county where half the land is Last man on earth hired dedicated to agriculture, and many of By Gus Pearcy know you are a finalist.