X Marks the Box: How to Make Politics Work for You by Daniel Blythe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Opposition-Craft': an Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitte

‘Opposition-Craft’: An Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of Politics and International Studies May, 2020 1 Intellectual Property and Publications Statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2020 The University of Leeds and Edward Henry Lack The right of Edward Henry Lack to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank Dr Victoria Honeyman and Dr Timothy Heppell of the School of Politics and International Studies, The University of Leeds, for their support and guidance in the production of this work. I would also like to thank my partner, Dr Ben Ramm and my parents, David and Linden Lack, for their encouragement and belief in my efforts to undertake this project. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those who took part in the research for this PhD thesis: Lord David Steel, Lord David Owen, Lord Chris Smith, Lord Andrew Adonis, Lord David Blunkett and Dame Caroline Spelman. 3 Abstract This thesis offers a distinctive and innovative framework for the study of effective official opposition politics in the United Kingdom. -

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

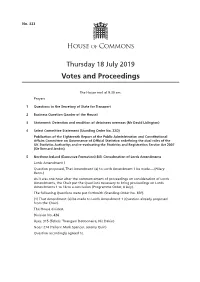

Votes and Proceedings for 18 Jul 2019

No. 333 Thursday 18 July 2019 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 9.30 am. Prayers 1 Questions to the Secretary of State for Transport 2 Business Question (Leader of the House) 3 Statement: Detention and rendition of detainees overseas (Mr David Lidington) 4 Select Committee Statement (Standing Order No. 22D) Publication of the Eighteenth Report of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee on Governance of Official Statistics: redefining the dual roles of the UK Statistics Authority; and re-evaluating the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 (Sir Bernard Jenkin) 5 Northern Ireland (Executive Formation) Bill: Consideration of Lords Amendments Lords Amendment 1 Question proposed, That Amendment (a) to Lords Amendment 1 be made.—(Hilary Benn.) As it was one hour after the commencement of proceedings on consideration of Lords Amendments, the Chair put the Questions necessary to bring proceedings on Lords Amendments 1 to 18 to a conclusion (Programme Order, 8 July). The following Questions were put forthwith (Standing Order No. 83F). (1) That Amendment (a) be made to Lords Amendment 1 (Question already proposed from the Chair). The House divided. Division No. 436 Ayes: 315 (Tellers: Thangam Debbonaire, Nic Dakin) Noes: 274 (Tellers: Mark Spencer, Jeremy Quin) Question accordingly agreed to. 2 Votes and Proceedings: 18 July 2019 No. 333 (2) That this House disagrees with the Lords in their Amendment 1 (as amended) (Question necessary for the disposal of the business to be concluded).—(John Penrose.) The House divided. Division No. 437 Ayes: 273 (Tellers: Mark Spencer, Jeremy Quin) Noes: 315 (Tellers: Thangam Debbonaire, Nic Dakin) Question accordingly negatived. -

US-UK Romance in Popular Culture

Pre-publication copy Final version in Brickman, B., Jermyn, D. and Trost, T. (eds). 2020. Love Across the Atlantic: US-UK Romance in Popular Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Holding hands as the ship sinks: Trump and May's special relationship Neil Ewen Introduction – A Titanic Disaster In August 2018, while talks between the United Kingdom and European Union to negotiate the terms of the UK's departure from the EU were dominating news cycles, a short film called Brexit: A Titanic Disaster went viral across social media platforms. Created by Comedy Central writer Josh Pappenheim, it mocked the prominent 'Leaver' and erstwhile British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson's comment that 'Brexit means Brexit and we are going to make a Titanic success of it' (Johnson 2016), and tapped into growing fears that the negotiations were going so badly that Britain was drifting towards the iceberg of a 'No Deal' Brexit in March 2019.1 Featuring scenes from James Cameron's iconic romantic blockbuster Titanic (1997), with the faces of high-profile politicians doctored into the footage, the film was watched more than ten million times in a matter of days (Townsend 2018). It begins with a foghorn bellowing and former Prime Minister David Cameron warning that 'there is no going back from this'. Then, as water begins to overwhelm the ocean-liner, his successor, Theresa May, urges the people to 'come together and seize the day'. Labour Party leader 1 Jeremy Corbyn, playing a slow lament on a violin, says 'the British people have made their decision', and an image of pound sterling falls off the ship and crashes into the water. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

United Kingdom Youth Parliament Debate 11Th November 2016 House of Commons

United Kingdom Youth Parliament Debate 11th November 2016 House of Commons 1 Youth Parliament11 NOVEMBER 2016 Youth Parliament 2 we get into our formal proceedings. Let us hope that Youth Parliament it is a great day. We now have a countdown of just over 40 seconds. I have already spotted a parliamentary colleague Friday 11 November 2016 here, Christina Rees, the hon. Member for Neath, whose parliamentary assistant will be addressing the Chamber erelong. Christina, welcome to you. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] 11 am 10.54 am The Youth Parliament observed a two-minute silence. Mr Speaker: Welcome to the eighth sitting of the UK Thank you, colleagues. I call the Leader of the House [Applause.] Youth Parliament in the House of Commons Chamber. of Commons, Mr David Lidington. This marks the beginning of UK Parliament Week, a programme of events and activities which connects The Leader of the House of Commons (Mr David people with the United Kingdom Parliament. This year, Lidington): I thank you, Mr Speaker, and Members of more than 250 activities and events are taking place the YouthParliament. I think you and I would probably across the UK. The issues to be debated today were agree that the initial greetings we have received make a chosen by the annual Make Your Mark ballot of 11 to welcome contrast from the reception we may, at times, 18-year-olds. The British Youth Council reported that, get from our colleagues here during normal working once again, the number of votes has increased, with sessions. 978,216 young people casting a vote this year. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

On Parliamentary Representation)

House of Commons Speaker's Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) Session 2008–09 Volume II Written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 21 April 2009 HC 167 -II Published on 27 May 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Speaker’s Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) The Conference secretariat will be able to make individual submissions available in large print or Braille on request. The Conference secretariat can be contacted on 020 7219 0654 or [email protected] On 12 November 2008 the House of Commons agreed to establish a new committee, to be chaired by the Speaker, Rt. Hon. Michael Martin MP and known as the Speaker's Conference. The Conference has been asked to: "Consider, and make recommendations for rectifying, the disparity between the representation of women, ethnic minorities and disabled people in the House of Commons and their representation in the UK population at large". It may also agree to consider other associated matters. The Speaker's Conference has until the end of the Parliament to conduct its inquiries. Current membership Miss Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) (Vice-Chairman) Ms Diane Abbott MP (Labour, Hackney North & Stoke Newington) John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Mr David Blunkett MP (Labour, Sheffield, Brightside) Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton & Honiton) Mr Ronnie Campbell MP (Labour, Blyth Valley) Mrs Ann Cryer MP (Labour, Keighley) Mr Parmjit Dhanda MP (Labour, Gloucester) Andrew George MP (Liberal Democrat, St Ives) Miss Julie Kirkbride MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove) Dr William McCrea MP (Democratic Unionist, South Antrim) David Maclean MP (Conservative, Penrith & The Border) Fiona Mactaggart MP (Labour, Slough) Mr Khalid Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham Perry Barr) Anne Main MP (Conservative, St Albans) Jo Swinson MP (Liberal Democrat, East Dunbartonshire) Mrs Betty Williams MP (Labour, Conwy) Publications The Reports and evidence of the Conference are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event.