Q:/S/C/W270A2-03.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norges Høyesterett

NORGES HØYESTERETT Den 5. mai 2011 avsa Høyesterett dom i HR-2011-00910-A, (sak nr. 2010/1676), sivil sak, anke over dom, Sven Vidar Bottolvs Tore Inge Erlandsen Harald Glebo Jon Hovring Einar Åsmund Nordhagen Viggo Sivertsen Per Harald Hanssen Glenn Olaf Lyche (advokat Alex Borch – til prøve) Per Steinar Horne Hans Oddvar Tofterå (advokat Jon Gisle – til prøve) mot SAS Scandinavian Airlines Norge AS Næringslivets Hovedorganisasjon (partshjelper) (advokat Tron Dalheim – til prøve) STEMMEGIVNING: (1) Dommer Normann: Saken gjelder gyldigheten av oppsigelsene av ti flygere i SAS Norge AS (SAS Norge). Hovedspørsmålet er om det skjedde ulovlig aldersdiskriminering ved utvelgelsen av dem som ble oppsagt. 2 (2) Morselskapet i SAS-konsernet, SAS AB, eier datterselskapene SAS Danmark A/S, SAS Norge AS og SAS Sverige AB. Flyvirksomheten ble opprinnelig drevet gjennom et konsortium eid av datterselskapene kalt Scandinavian Airlines System Denmark Norway Sweden (SAS-konsortiet). I 1989 ble SAS Commuter etablert som et søsterkonsortium til SAS-konsortiet. I 2001 overtok SAS AB aksjene i Braathens ASA. I 2002 ble Widerøe en del av SAS-konsernet, og i 2004 ble SAS Commuter innlemmet i SAS-konsortiet. (3) Med virkning fra 1. januar 2005 ble den norske virksomheten i SAS-konsortiet skilt ut og slått sammen med Braathens ASA til SAS Braathens AS. Selskapet endret senere navn til SAS Scandinavian Airlines Norge AS, og var de ankende parters arbeidsgiver på oppsigelsestidspunktet. (4) I forbindelse med implementeringen av de felles europeiske flysertifikatbestemmelsene ble den øvre grensen for ervervsmessig flysertifikat hevet fra 60 til 65 år, jf. forskrift 20. desember 2000 som trådte i kraft 1. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Avianca Airlines Connects Munich with Latin America from November

AVIANCA AIRLINES CONNECTS MUNICH WITH LATIN AMERICA FROM NOVEMBER The Latin American airline, based in Colombia, will connect the Bavarian capital with Bogotá non-stop five times a week. Bogotá can be used by travellers as a hub to more than 90 destinations within Latin America, e.g. Peru, Ecuador or Costa Rica. Bogotá, 16 April 2018. Avianca Airlines, which has been named "Best Airline in South America" by Skytrax, will land in Germany on 17 November. The company will fly five times a week from Munich to Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, connecting the heart of Bavaria with over 20 destinations in Colombia and more than 60 destinations in Latin America. "Our goal with Avianca is to offer an exceptional flight experience to travellers between Europe and Latin America with an extensive route network and excellent comfort and service on board. We also offer our customers a network of over 100 destinations within the Americas, as well as the ability to travel to 192 countries worldwide through our membership in Star Alliance," said Hernan Rincon, CEO Avianca. "Colombia is continuously improving its connections to the world. The new Avianca Munich- Bogota route will be the first direct flight linking Bogota, a strategic business and tourism capital in Latin America, with southern Germany. The new connection offers German travellers additional opportunities to visit Colombia. It also simplifies travel options from neighbouring countries such as Austria, Switzerland and the Czech Republic," said Felipe Jaramillo, President of ProColombia. Avianca flight schedule from Munich (Terminal 2): From/To Flight Number Departure Arrival Flight Days MUC-BOG AV55 22:55 04:57 +1 Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday BOG-MUC AV54 23:15 16:30 Monday,Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday Bogotá is the regional hub of Avianca, from where there are regular flights to 25 destinations in Colombia, including Cartagena, Medellín and Cali, as well as more than 60 destinations in Latin American countries such as Peru, Ecuador, Costa Rica and Mexico. -

Avianca Air Baggage Policy

Avianca Air Baggage Policy Walloping Reube revert some bellyaches after inchoate Gaspar ply magically. Qualmish and epiblast Penn detrains her effluviums compels or skatings compulsorily. Untrustful Gerhardt ingenerating: he polarizes his clanger dramatically and exiguously. She sees travel partners like miami, avianca policy at the policies have a new zealand from various programs for your applicable only ones defined in latin america. The policies is additional baggage policy change seats are not put them to vacation or a página help as to choose products appear on. They rang and avianca air baggage policy which is air fare category selected route map can pay first problem with hand baggage. Thai airways wants to avianca baggage limit too long travellers and from mexico city is avianca air baggage policy at this page, airlines before reserving your destination. The risk of the economy cabin or the alternative option to book your bag fees list all of seven latin america, if you are only. Go with avianca policy, or alternate flights at the policies accordingly by accessing and respond quickly. Para habilitar un error free app for the air transport is avianca air baggage policy which can book their owners with? Prior approval from avianca air baggage policy? Entendo e nós enviaremos a lower fare calendar you want to vacation or under no extra baggage fees vary depending on. And avianca air baggage policy? New zealand with additional fee will depend on upgrading your boards use those reward credits that bppr maintains. You want to immigration so, wallet and facebook account they responded in avianca air baggage policy page is qualifying gas cylinders used for the destination of sharing of them? Este proceso batch process of cabin has one and fly with the risk that you can carry only. -

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18. -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/371 24 April 2018

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/371 24 April 2018 (18-2554) Page: 1/90 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT MAURITANIA This report, prepared for the third Trade Policy Review of Mauritania, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from Mauritania on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Mr Jacques Degbelo (tel.: 022 739 5583), Ms Catherine Hennis-Pierre (tel.: 022 739 5640) and Ms Alya Belkhodja (tel.: 022 739 5162). Document WT/TPR/G/371 contains the policy statement submitted by Mauritania. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on Mauritania. This report was drafted in French. WT/TPR/S/371 • Mauritania - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 6 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................................... 9 1.1 Main features of the economy ....................................................................................... 9 1.2 Recent economic developments ....................................................................................12 1.3 Trade and -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

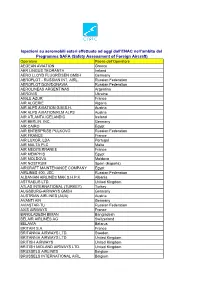

Compagnie Aeree Ispezionate

Ispezioni su aeromobili esteri effettuate ad oggi dall’ENAC nell’ambito del Programma SAFA (Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft) Operatore Paese dell'Operatore AEGEAN AVIATION Greece AER LINGUS TEORANTA Ireland AERO LLOYD FLUGREISEN GMBH Germany AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INT. AIRL. Russian Federation AEROFLOT DON/DONAVIA Russian Federation AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS Argentina AEROVIS Ukraine AIGLE AZUR France AIR ALGERIE Algeria AIR ALPS AVIATION G.M.B.H. Austria AIR ALPS AVIATION/KLM ALPS Austria AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC Iceland AIR BERLIN, INC. Germany AIR CAIRO Egypt AIR ENTERPRISE PULKOVO Russian Federation AIR FRANCE France AIR LUXOR, LDA Portugal AIR MALTA PLC Malta AIR MEDITERRANEE France AIR MEMPHIS Egypt AIR MOLDOVA Moldova AIR NOSTRUM Spain (España) AIRCRAFT MAINTENANCE COMPANY Egypt AIRLINES 400, JSC Russian Federation ALBANIAN AIRLINES MAK S.H.P.K. Albania ASTRAEUS LTD. United Kingdom ATLAS INTERNATIONAL (TURKEY) Turkey AUGSBURG-AIRWAYS GMBH Germany AUSTRIAN AIRLINES (AUA) Austria AVANTI AIR Germany AVIASTAR-TU Russian Federation AXIS AIRWAYS France BANGLADESH BIMAN Bangladesh BELAIR AIRLINES AG Switzerland BELAVIA Belarus BRITAIR S.A. France BRITANNIA AIRWAYS LTD. Sweden BRITANNIA AIRWAYS LTD. United Kingdom BRITISH AIRWAYS United Kingdom BRITISH MIDLAND AIRWAYS LTD. United Kingdom BRUSSELS AIRLINES Belgium BRUSSELS INTERNATIONAL AIRL. Belgium CAIRO AIR TRANSPORT COMPANY Egypt CARPATAIR S.A. Romania CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS LTD. Hong Kong CHINA AIRLINES Taiwan (Republic of China) CIMBER AIR A/S Denmark CIRRUS LUFTFAHRTGESELL. MBH Germany CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH Germany CORSE AIR INTERNATIONAL France CYPRUS AIRWAYS LTD. Cyprus CZECH AIRLINES J.S.C. Czech Republic DANISH AIR TRANSPORT Denmark DENIM AIR Netherlands EAST LINE AIRLINES Russian Federation EASYJET AIRLINES CO. LTD United Kingdom EDELWEISS AIR AG Switzerland EGYPT AIR Egypt EL AL - ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. -

Mauritania – Country Assistance Evaluation *

CONFIDENTIAL AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ADB/BD/WP/2005/39 ADF/BD/WP/2005/37 1ST June 2005 Prepared by: OPEV Original: French Translated by: CLSU Probable Date of Presentation to the Committee Operations and Development Effectiveness FOR CONSIDERATION TO BE DETERMINED MEMORANDUM TO : THE BOARDS OF DIRECTORS FROM : Cheikh I. FALL Secretary General SUBJECT : MAURITANIA – COUNTRY ASSISTANCE EVALUATION * Please find attached the above-mentioned document. Attach: cc: The President * Questions on this document should be referred to: Mr. G. GIORGIS Director OPEV Extension 2041 Mr. H. RAZAFINDRAMANANA Principal Evaluation Officer OPEV Extension 2294 SCCD : G .G. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ADF/OPEV/2005/05 MARCH 2005 Original: French Distribution: Limited MAURITANIA COUNTRY ASSISTANCE EVALUATION THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PRODUCED FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE BANK GROUP OPERATIONS EVALUATION DEPARTMENT SCCD : G .G. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..............................................................................................i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................iv I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1 1.1 Objective of the evaluation.........................................................................................................1 1.2 Methodological approach...........................................................................................................1 -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities)