The Struggle Between the Dutch and the Portuguese for the Control of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Free Negroes" - the Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 12-16-2015 "Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670 Patrick John Nichols Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Nichols, Patrick John, ""Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/100 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FREE NEGROES” – THE DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ENGLISH JAMAICA AND THE BIRTH OF JAMAICAN MAROON CONSCIOUSNESS, 1655-1670 by PATRICK JOHN NICHOLS Under the Direction of Harcourt Fuller, PhD ABSTRACT The English conquest of Jamaica in 1655 was a turning point in the history of Atlantic World colonialism. Conquest displaced the Spanish colony and its subjects, some of who fled into the mountainous interior of Jamaica and assumed lives in isolation. This project reconstructs the historical experiences of the “negro” populations of Spanish and English Jamaica, which included its “free black”, “mulattoes”, indigenous peoples, and others, and examines how English cosmopolitanism and distinct interactions laid the groundwork for and informed the syncretic identities and communities that emerged decades later. Upon the framework of English conquest within the West Indies, I explore the experiences of one such settlement alongside the early English colony of Jamaica to understand how a formal relationship materialized between the entities and how its course inflected the distinct socio-political identity and emergent political agency embodied by the Jamaican Maroons. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of the Life of Columbus, by Arthur Helps

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of Columbus, by Arthur Helps This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Life of Columbus Author: Arthur Helps Release Date: March 12, 2005 [EBook #15336] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF COLUMBUS *** Produced by Don Kostuch Transcribers Notes: Several non-English proper names have been rendered in ASCI, omitting the proper accents. The following glossary provides references and definitions of unfamiliar (to me) terms and names. Adelantado Governor or commander. Refers to Don Bartholomew Columbus (brother of Christopher) in this volume. Angelic Doctor: Thomas Aquinas Arroba In Spanish-speaking countries, about 25 pounds. In Portuguese-speaking countries, about 32 pounds. Aught Anything whatever. Bartholomew Columbus Brother of Christopher Columbus. Cacique Indian chief in the Spanish West Indies. Ca da Mosto or Cadamosto Alvise Ca' da Mosto, (1432-1488) Venetian explorer and trader who wrote early accounts of western Africa. Caonabo Cacique (chief) who destroyed the first garrison at La Navidad. Cave of Adullam About 13 miles west of Bethlehem where David gathered together "every one that was in distress, and every one that was in debt, and every one that was discontented" (1 Sam. 22:2). Cipango Japan. Compeer Person of equal status; a peer. Contumely Contempt arising from arrogance; insolence. Cosmography Study of the universe, including geography and astronomy. -

La Lettre Energy Geotechnics

La Lettre Energy Geotechnics Special release / August 2015 Alstom power plants Editorial A long-lasting partnership Energy engineering in the broadest sense brings together a multitude of skills, among A specific sequencing of the geotechnical which geotechnics may seem marginal. engineering tasks has therefore been This is not the case at all, as TERRASOL developed: demonstrates every day through its • Analysis of available data (often limited) contribution to a variety of projects and initial feasibility study focusing on (hydroelectric power, oil & gas, wind turbines, the general principles of geotechnical thermal power plants, nuclear power, etc), in structures (types of foundations that all regions of the world. can be considered, soil consolidation/ reinforcement issues, dewatering, etc), Projects related to hydroelectric power • Drafting of the first version of the Soil give rise to serious geological and Baseline Assumptions report, the geotechnical issues because of the types baseline document of the call for tenders of structures they involve (dams, tunnels), phase which defines the assumptions and TERRASOL has been working on such made by ALSTOM for its costing and projects practically since it was founded, which may become contractual, thanks to its competencies in underground • Preparation of the first version of the structures and slope stability. Soil Risk Analysis report, in order to get insight into the identified risks of slippage, Centrale HEP Plomin, Croatia Large storage tanks are another of our • Preparation of the specifications for the preferred areas of work, because of the Since 2006 and a first expert assessment additional soil testing intended to obtain pertinence of our approaches in soil-structure report on problems on a power plant site in data that is lacking and/or for which the interaction. -

Glossary of Historical and Geographic Names and Some Linguistic Explanations

Glossary of historical and geographic names and some linguistic explanations (by Dolores Turró, translator of Quieros presentation memorials held in Mitchell & Dixson Libraries) Accents, use of (´): Accents indicate a stressed syllable in Spanish. They have phonemic value, in other words, there are examples of words that are spelt the same, but that change their meaning depending on whether there is an accent or not. Example: duro (= hard) and duró (= he/she/it lasted). In the translated memorials, geographic and family names in modern Spanish have been kept with their graphic accents. Adelantado: According to the Collins English Dictionary, Adelantado is a a military title given to Spanish Conquistadors allowing the bearer the right to become governor or justice of a region. The word Adelantado was explained or translated as “pioneer” in the Memorials. America / América: Name used in Spanish to refer to the Americas. The New World where Christopher Columbus arrived in his first discovery voyage was named after Amerigo Vespucci (in Spanish, Américo Vespucio, 1454-1512). Columbus died believing he had found a new route to Asia, when he had actually arrived at a new, uncharted continent. The word “America” has been kept in the translation because that was the name effectively used when Quirós wrote his memorials. Aniam or Anian (in Spanish Anián) Strait: In the Memorials, the spelling is as inconsistent as that of other geographic names. In any case, it still refers to the Northwestern Passage, as first mentioned in a 1562 pamphlet published by the Venetian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi (1500-1566). Bay of St Philip (San Felipe) and St James (Santiago) / St Philip and St James Harbour: both the Spanish and the English name were used interchangeably in the translation. -

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture From

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 i v ABSTRACT The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Christina Frances Mobley 2015 Abstract In my dissertation, “The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti,” I investigate the cultural history of West Central African slavery at the height of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the late eighteenth century. My research focuses on the Loango Coast, a region that has received -

T. R. Brainerd2

KSHOP IN POLmCM, AND POLICY ANAiV 513NQ&THPAPM INDIANA UNlVfiW BLOQMHXi-STON, JN0IANA _ p^ THE SARDINELLA FISHERY OFF THE COAST OF WEST AFRICA; THE CASE OF A COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCE by T. R. Brainerd2 Paper presented at the Second Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP), September 26-29, 1991, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. Fisheries Economist Intern, Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Sciences Division/International Development Research Centre (AFNS/IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. THE SARDINELLA FISHERY OFF THE COAST OF WEST AFRICA; THE CASE OF A COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCE by T. R. Brainerd Fisheries Economist Intern Agriculture/ Food and Nutrition Sciences Division/ International Development Research Centre (AFNS/IDRC) P.O. Box 8500, Ottawa/ Ontario/ CANADA RIG 3H9 Abstract Two species of sardinella/ 5. aurita and S. maderenele occur off the coast of West Africa in the Eastern Central Atlantic. Their distribution extends from Mauritania to the south of Angola with concentrations of distinct populations in three geographic sectors due to favorable environmental conditions. Because of their pattern of migration (both up and down along the coast and inshore- offshore pattern of movements)/ individual stocks are found in the territorial waters of two or more coastal countries at different stages of their life cycles. This makes it necessary for coastal countries to share information on the status of the stocks and for cooperation on the management of the fishery. The activities of national institutions/ sub-regional and regional bodies/ and international agencies in promoting the management of this common property resource are highlighted and discussed in terms of their effectiveness and relevance. -

The Maritime Dimension of the European Union's and Germany's

ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security Issue The Maritime Dimension of the European Union’s and Germany’s No. 229 Security and Defence Policy in the 21st Century May 2013 The Maritime Dimension of the European Union’s and Germany’s Security and Defence Policy in the 21st Century Maritime Security of the European Union (MAREU) Prof. Dr. Carlo Masala and Konstantinos Tsetsos, M.A. May 2013 Executive Summary This study focuses on the centres of gravity and goals of a future maritime security policy of Germany and the European Union (EU) for the 21st century. Prepared under the working title MAREU (Maritime Security of the European Union) the project concentrates on the EU’s maritime security environment. The strategic dimension of security related developments at the European periphery, Germany’s and the EU’s maritime and energy security represent the central political and societal research objectives of the MAREU project. This study addresses economic developments, legal and illegal migration as well as existing maritime security measures of international organisations. The Mediterranean, Baltic Sea, Gulf of Guinea and South China Sea are the study’s geographical focus. The project discusses the necessary framework for a German and European maritime security strategy by anticipating potential future security threats and an analysis of existing national and international strategies and measures. In its conclusion the study outlines the required future capabilities of the Bundeswehr and offers guidelines, recommendations and reform proposals in order to enhance the future coordination of German and European maritime security cooperation. About ISPSW The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy (ISPSW) is a private institute for research and consultancy. -

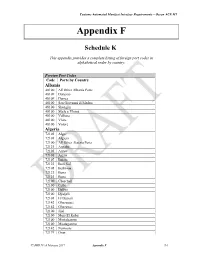

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

The South Atlantic, Past and Present

FI LI PA RIBEIRO DA SILVA The Dutch and the Consolidation of the Seventeenth-Century South Atlantic Complex, c. 1630-1654 abstract: This article looks at the seventeenth-century South Atlantic and explores the role played by the Dutch private merchants based in Brazil and by the Dutch West India Company for the consolidation of the South Atlantic. To do so, it focuses on the political, military, and commercial exchanges between the northeastern Bra- zilian captaincies and Angola during theyears 1630 and 1654. keywords: Dutch—Commerce—South Atlantic In recent years, scholarship on the Atlantic economy has clearly shown that throughout the early modern period the South Atlantic emerged as an economic, social, political, and cultural complex with a life of its own, in most cases oper- 1 ating independently from colonial powers based in Europe. Historiography and information recently gathered in the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (tstd) have also demonstrated that the formation of the South Atlantic com- plex dates back to the 1570s, and its rise in the overall Atlantic economy starts to 2 be most visible after the mid-seventeenth century. Most studies on this southern complex, however, have focused mainly on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the zenith of South Atlantic exchanges. 3 With the exception of works by Alencastro and Puntoni, among others, little is known about the South Atlantic complex in the period between the 1570s and 1650s and about the impact of the arrival of northern European merchants, par- ticularly those from the Dutch Republic (hereafter the Republic), in the South Atlantic and the role they might have played (or not) in the formation and con- solidation of the complex. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade To

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: JOSEPH BE1TEY, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. Assistant Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XLII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 EDITED BY DAYID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1991 ISBN 0 901538 12 4 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Bristol Record Society wishes to express its gratitude to the Marc Fitch Fund and to the University of Bristol Publications Fund for generous grants in support of this volume. Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Stroud, Glos. Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction . vii Note on transcription xxxii List of abbreviations xxxiii ·Text 1 Index 235 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of ·compiling and editing the information on Bristol voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have received assistance and advice from various individuals and organisations. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice I received from the staff at the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to cite material from them. I am also indebted to the British Academy for its generosity in awarding me a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade to America, Vol 1

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A. Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXVIII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698--1729 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698-1729 EDITED BY DAVID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1986 ISBN 0 901583 00 00 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction vii Note on transcription xxix List of Abbreviations xxix Text 1 Index 193 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of compiling and editing the information on Bristol trading voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have been fortunate to receive assistance and encouragement from a number of groups and individuals. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice given to me by the staffs of the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Mer chant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to use material from them. My thanks are due also to the British Academy for its generosity in providing me with a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. Finally I am indebted to Miss Mary Williams, the City Archivist in Bristol, and Professor Patrick McGrath, the General Editor of the Bristol Record Society, for their warm response to my initial proposal for this volume and for their guidance and help in bringing it to fruition. -

Gulf of Guinea

Gulf of Guinea Sea - Seek Ebook Sailing guide / Guide nautique Gulf of Guinea NE Atlantic Ocean September 2021 http://www.sea-seek.com September 2021 Gulf of Guinea Gulf of Guinea http://www.sea-seek.com September 2021 Gulf of Guinea Table of contents Gulf of Guinea...................................................................................................... 1 1 - Romanche Trench .......................................................................................... 3 2 - Sierra Leone.................................................................................................... 5 2.1 - Freetown - Ferry Terminal ................................................................... 5 3 - Liberia ............................................................................................................. 7 3.1 - Monrovia .............................................................................................. 7 4 - Abidjan............................................................................................................ 8 5 - Takoradi.......................................................................................................... 8 6 - Sekondi ............................................................................................................ 9 7 - Tema .............................................................................................................. 10 8 - Port De Lome................................................................................................ 11 9 - Cotonou ........................................................................................................